Arjun Jayadev at Triple Crisis provides a quote from Thomas Phillipon that somehow never sees the light of day in the financial press:

…the unit cost of intermediation is higher today than it was a century ago, and it has increased over the past 30 years. One interpretation is that improvements in information technology may have been cancelled out by increases in other financial activities whose social value is difficult to assess.

This of course is a very understated way of suggesting that the bankers have found new ways to sell or bundle other products or services along with the ones made cheaper by information technology, or create new ones of dubious additional value, so as to allow them to fatten their total pricing.

This is a big and important topic, so let me take just an initial slice at it, and I’ll hopefully come back to it in future posts. We can certainly see the net effect, which is the financialization of the economy, which suggest that IT (and other developments) have allowed the banks to move into an oligopoly position and are extracting economic rents. Simon Johnson, in his important 2009 article, The Quiet Coup, described how the financial sector had accomplished the surprising feat of increasing average worker pay packages and increasing their share of GDP. Wages rose from roughly comparable to average private sector worker wages from just after World War II through 1982. They increased to 181% of private sector worker wages right before the crisis. From 1973 to 1982, the financial sector never garnered more than 16% of corporate profits. By the 2000s, it hit 41%.

On the client side, lower transactions costs (which are not attributable solely to IT but to deregulation of commissions on the equity side, and to end of the requirement to make physical delivery of securities) have led to higher transaction volumes, raising the question of social utility. It’s conventional to see lower cost trading as a benefit, but is it really? Traders benefit from trading. Bona fide investors (are there any left?) might actually benefit from having to have a sense of commitment before buying, that the costs of trading were high enough that you actually need to think before you jump into a particular instrument. The reason that women are found to be better investors is that they are less inclined to overtrade. Higher transaction costs similarly discourage overtrading.

Again on the client side, a host of new products have come into being, and again, I’m skeptical that the net result is value added for customers. Of course, we have to define who we mean as “customer” since we have a huge agency problem. For instance, the rise of complex, customized derivatives is utterly dependent on the rise of more robust IT platforms. The early leaders in the OTC derivatives business, Chicago Research & Trading, O’Connor, and Bankers Trust, all had to have state of the art capabilities and highly competent IT professionals because you were at bleeding edge to model large derivatives books and their related hedges on a real time basis. But as anyone who has read Frank Partnoy’s Fiasco or Satyajit Das’ Traders, Guns, and Money knows, a very high proportion of complex derivatives trades are for tax or regulatory arbitrage, playing accounting games, or just ripping off customers (as in talking them into something more complicated with hidden margin or hidden risks loaded in). So complicated derivatives are perfect for predation.

So why do customers buy them? The customers are seldom the real customers. They are usually agents, most often, fund managers or employees. Fund managers are victims of benchmark-driven herd behavior: if there colleagues are using derivatives to boost returns, they have to as well, even if the result is to eke out a few extra basis points now for more downside later. Other agents have similarly bad incentives. If you are a county commissioner, you can’t say: “I know Wall Street is a con, we have a ten year project, we can finance it with ten year bonds, the math works, let’s go ahead.” No, you will be accused of being lazy and having left money on the table for not having investigated your options. So you hire a consultant. The consultant’s incentives are to find as many complex structures as possible to review, that makes his job more difficult and justifies a big fee. And he can’t recommend a simple ten year bond after all that work. That would call his existence into question. So even if he is not affirmatively corrupt (as in steering business to buddies for kickbacks), he’ll recommend something complicated he may not really understand, and it is certain his client won’t understand. And his client will be hung on the bottom line. If something offers apparent cost savings, he as a public official can’t buck that. Cost savings are easy to understand. Complex, hard to characterize risks are not. And that is how municipality after municipality (heck, Harvard’s own supposedly sophisticated management company) gets fleeced. But the more complicated all these people’s jobs appear to be, that of the consultant, the fund manager, the county commissioner, the more they can claim they deserve higher pay. So they win from the complexity game, even as the people they represent wind up losers.

By Arjun Jayadev, an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Cross posted from Triple Crisis

One of my favorite lines from recent economics papers is the following one from this paper by Thomas Phillipon, who in talking about the performance of the financial sector suggests that “the unit cost of intermediation is higher today than it was a century ago, and it has increased over the past 30 years. One interpretation is that improvements in information technology may have been cancelled out by increases in other financial activities whose social value is difficult to assess.”

The claim that the financial sector has been ‘functionally inefficient’ was made 30 years ago by James Tobin, and it’s great to have a quantitative basis to make this sort of judgment. Another way to have some sort of handle on the degree to which intermediation has become more expensive is to look at the spread between funding costs and lending rates.

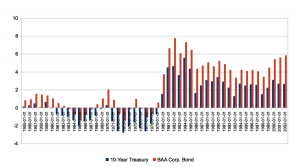

To revisit a theme expressed before on this blog, if one takes a long-term perspective, the idea that inflation adjusted interest rates were especially low in the 2000s is simply mistaken, and there were long periods in the post war to 1980 period that saw very low interest rate facing end borrowers (consumers and non financial corporations). Given the fact that short policy rates—the federal funds rate—were indeed at historical lows in the early 2000s suggests that there have been rising spreads. The figure below—from the latest draft of a paper by JW Mason and I– is the 10-Year Treasury and BAA Corporate Bond rates relative to the 10-Year Ahead Average Federal Funds Rate. It’s asking how much interest a financial intermediary could make borrowing at the Fed funds rate over 10 years and lending to Treasury and corporates. I suppose we could have done some sort of structural break analysis, but really, it’s all there in the graph. After 1980, in the Brave New World of Neoliberal Finance, the 30 years that Phillipon writes about saw a sharp increase in spreads compared to the period before.

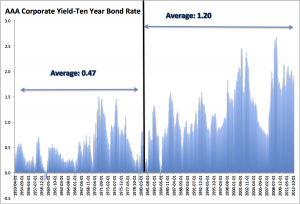

This in itself is of course not enough to suggest that intermediation has become less efficient. Certainly, it is possible that these rising spreads might be because of increased perceived or actual default risk. Well maybe, but the following figure gives some reason to doubt that story.

The graph shows the difference in spreads between corporate bonds with AAA ratings from Moody’s at the time of issuance and the 10 year treasury bond rate. The spread between the AAA corporate yield and the 10 year bond rate also began to rise around the same time (i.e around 1980). Since 1980, however, the annual default rate on bonds of corporations with AAA ratings at issuance, has been approximately 0.05 percent. Given an average recovery rate of around 50 percent, the default losses have been about half that. But the premium of AAA bonds over 10-year treasuries has been 1.2 percent (i.e. more than 40 times the expected annual default loss).

This is an example of the “credit spread” puzzle. We chose AAA bonds as a comparator, but the same pattern exists across different classes of Bonds. The spread on triple B bonds (as the link suggests) was 8 times the default on those loans.

So what is behind these spreads? Josh and I are agnostic. Several candidates spring to mind, but one in particular seems most interesting, especially from a Minskyian/Post-Keynesian point of view. From such a starting point, asset holdings are not driven by households maximizing their expected utility from consumption through the solution of an Euler equation. Rather, the impetus for any agent to hold an asset is to achieve positive returns while keeping the probability of being able to meet all current obligations above some threshold. In this sense, the importance of holding liquid assets is to protect against bankruptcy if contracted cash payments cannot be made. The implication of this position is that the demand for liquidity will depend strongly on how likely lenders believe they are to face the risk of insolvency. The broader implication is that the observed credit spread may depend critically on the the probability assigned by banks and other financial institutions of falling short on cash to meet obligations, and thus the greater premium they will pay for liquid assets such as government bonds, thereby increasing spreads between those and other long rates.

This is not an explanation, of course of why treasuries have higher rates after 1980 than before and for that we’ll need additional explanations.

Do readers have other hypotheses/thoughts?

Thanks, Yves. I really enjoyed reading both the article and your comments. A couple of thoughts:

1. I find economics, more than any other academic discipline, suffers from acute reification. In other words, economists seem to fall into the trap of believing their abstractions, theoretical constructs, and conceptualizaions are actually real physical objects that have measureable (as in rule and temperature) properties and deterministic behavior. I recall you make this point in ECONNED, but I think no one stresses this delusional behavior enough.

Over many years, I’ve notice the following progression:

similie → metaphor → delusion.

In some ways, our minds are a little too pliable. The same mental capabilities that allow us to conceive of such elaborate abstractions and non-physical concepts as mathematics and physics also lead us into “living” in our fantasy worlds. Fama’s magically infallably rational EMH is a great example.

Of course, while the delusion may be “mass”, even to the point of defining a culture or sub-culture, it isn’t complete. A few, even quite a few, “Neos” will clue into the delusion. Some will quite and move on to more realistic pastures that actually smell like pastures; but others will see the opportunity for gain, realizing they are living in a world of fools.

2. Related to 1., I really knew we hit the massively mass delusional stage when I noticed that finance had adopted (really bastardized) the terminology of engineering. When twenty-something MBAs start referring to themselves as “financial engineers” that create customized “products” having a precisely defined “risk profile”. When the financial industry promises they can make investments “risk-free”, actually claiming that they have “conquored risk”, or they can give any investment any degree of risk, as if they control risk like the dial of rheostat, you know you’re no in Kansas (or the reality-based world) any more.

So, given this I’m not sure if you can find a completely rational explanation for the behavior deescribed at the end of the article. Sure, there are broad “forces” at work, but if the participants are largely of the reational market cult, egged on and sustained by marketing departments that really ladel the kook aid for both the customers and the servicers, can you really expect to find a “rational” explanation, i.e., an explanation that deomonstates a cause-and-effect sequence of rational actions? Or is the truth more disappointing–the market is simply deranged, and no one can ever expect to exmplain the actions of a deranged person solely in rataional terms.

You’ve certainly described it well. I call it “marketing”. It is the marketing of financial and investment products/services. Very powerful pursuasive force. Even very smart persons get sucked in by it.

I studied in math and one thing I have noticed over the last 2 decades is that those in power are more often than not nnumerate. Most have only taken introductory math classes where they learned how to use the formulas but never really learned what they meant.

So many in the finance industry are using complex math theories WRONG. If there is an industry that has promoted pseudo-science it is definitely finance.

Don’t forget that many who created our out-of-control derivatives and other financial “products” were PhD mathematicians and physicists. True, many of the senior executives at financial institutions don’t understand the details, but the scientists and mathematicians provide the basic grist for the mill.

Baloney. Look at LIBOR and the latest article about it on yesterday’s counterpunch.org!

When the foxes are running the henhouse, mathematics goes out the window!

The American public and their local governments are being taken to the cleaners. There’s no science in that!

Without even getting into a long discussion of the history of Modernism and the ultimate reasons why your comment lacks veracity, there are the proximate reasons why your comment lacks veracity. These are set out by Benoit Mandelbrot in The (Mis)Behavior of Markets and Nassim Nicholas Taleb in The Black Swan. As Taleb sumises:

What do you mean, “using” it “WRONG”? They’re making a ton of money, right?

He means that they’re using the “mathematical model” as a smokescreen to *appear* legitimate to the people they’re defrauding. But they don’t actually know how to use it as a, you know, mathematical tool.

The fundamental problem we have is that fraudsters have been allowed to take control of most of the economy and most of the government. This is not tolerable; it violates basic, core ethical principles which 90% of humans have. It’s also not sustainable.

Ethics » Laws » Regulations » Break Laws + Regulations » Jail

Rich >> Ignore ethics >> Change laws >> Deregulate >> No jail

Banks will either change the wording, or pay off Congress to write in a loophole. Regulating banks is like stabbing a knife into fog – the knife goes in, but the regulation never hits anything because the bank finds a way to slip around it.

The entire universe between a and b: $=$a; $a=$a…; $a…=I can do whatever I need to do*; (*=b).

Brilliant.

This is the appeal to and belief of the financial “wizards”.

Even those who don’t understand that formula and most probably do not.

I wonder if it is a generational effect.

By this i draw a comparison to religion, where rules of thumb for survival for one generation ends up being DO (NOT) OR SUFFER ETERNAL DAMNATION some 5-10 jumps down the chain.

This because future generations are not aware of the reasons behind the rules, only the application of them. In essence, context is lost as the degrees of separation grows.

It seems that both Treasuries and corporate bonds have lost much of their meaning in being tied to various derivative products and fraudulent activities. Both are being used inappropriately to fund asset appreciation and corporate raids and speculation rather than productive activity.

“”This creates a symbiosis among the economy’s rent-yielding sectors. Some 80 percent of bank loans are real estate mortgages, and the balance of loans are to buy financial securities already issued or to take over companies, or consumer loans to be paid out of revenue earned in the normal course of employment, not by investing the bank credit productively. Even in the case of U.S student loans (whose volume now exceeds that of credit card debt), this lending has not enabled many students to earn enough return on their education to pay their creditors. As debt deflation shrinks the economy, there are few employment opportunities for new graduates.””

“”And all economic logic of the 19th and early 20th century assumed the rule of law. But today, junk mortgage lending and outright fraud are proliferating on an unprecedented scale.””

“”Recent financial give-aways to recipients of the $13 trillion in post-2008 U.S. financial bailouts that have endowed a power elite to rule the 21st century.”” (Michael Hudson, ‘The Bubble and Beyond’)

Unwinding the fraud, complex derivative products and tax advantages etc to the rentiers as well as acknowledging the extractive rather than the productive role of the financial industry will help us get a more realistic picture of the real economy.

I think you have just unwound the entire private banking fantasy in little more than a single paragraph, which betrays the main post for the errant nonsense it clearly is.

Arjun Jayadev dazzles us with some awesome reasearch, but then comes to completely erroneous conclusions, based as they are on neoclassical (Krugman’s) monetary theory.

For example, Jayadev says

However, as Kevin Phillips scrupulously documents in Bad Money, the TBTF banks and hedge funds are not the ones who absorb the losses for their poor lending decisions. That role has largely been transferred to the US taxpayer. I refer to Phillips’ FIGURE 2.7 U.S. Financial Mercantilism: Bailouts, Debt, and the Socialization of Credit Risk, 1982-2007. Since 1982 — a date that not unsurprisingly correlates with the upsurge in interest rate spreads — Phillips counts a total of 12 incidents where the US government has stepped in to bailout the banks and hedge funds for their derelict risk management, with of course the grandaddy of them all beginning in 2007, a bailout still very much in progress.

Then Jayadev regales us with this, which although widely believed amongst both neoclassical economist and layman, is mythology, having no basis in reality:

What Jayadev regurgitates is unmitigated neoclassical — loanable funds — monetary theory, and it is Krugman’s touting this defactualized nonsense that caused the big knock-down drag-out between Krugman and Steve Keen last year. As Keen points out in the following video, “neoclassical economists don’t know anything about banks, debt and money.”

In Keen’s endogenous monetary theory:

1) Banks are not the same as households, since banks have the power to create money out of thin air — with the stroke of a keyboard as Michael Hudson is fond of putting it — and households don’t, and

2) Banks create money out of thin air, so money doesn’t have to be saved by households before banks can lend it out.

Just finished trying to read (im no economist) Minsky’s Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, and he reckons the Fed and other entities have been lenders of last resort since the 1966 credit crunch with other crises in 1970, 1974-75, 1979-80 and 1982-83. One of the problems seems to be that as soon as one crisis is over a new financial instruments come along that lead to another and the economy vasilates between debt-deflation financial crisis and bursts of acclerating inflation. But read the book if you havent already, because my little synopsis is woefully inadequate.

I want to create money out of thin air. It just requires the right kind of charisma.

Heck, someone from my town — Paul Glover — *DID* create money out of thin air. And it worked, as money, until he left town.

The other thing that is crucial to recognize is that the financialization of the economy did not occur without a massive upsurge in state violence — the phenomenal growth of the security state: police, prisons, and military.

The BIG LIE we’ve been peddled for the past 200+ years is that economics exists in its own litte universe, disconnected from politics, e.g., the state’s instruments of violence.

Analyses such as Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism and Christian Parenti’s Lockdown America show this lie for the self-serving canard that it is.

I am fascinated by the agency question. Why indeed does wall street still have institutional clients after being treated as muppets: hello bid rigging, hello libor, hello jefferson county…

Because the county commissioners, pension boards, and mutual fund managers are all spending other peoples money.

I was on a small pension board. The incentives are to follow the herd; there are huge disincentives even personal risk to go off script. Its fine to go off a cliff so long as all your peers are there with you.

What are the units in the unit cost? How do you measure value added of the financial sector?

It’s not necessarily that unusual that as society gets richer, has more retirees, you would have a bigger financial sector.

If you measure cost of the financial sector per unit of GDP or annual investment dollar it wouldn’t be surprising costs have risen.

With higher wealth, increased financialization, low interest rates=high asset prices, financial assets/GDP must have exploded.

If you measure the cost of the financial sector per dollar of financial assets and find it has risen, that would be a depressing result.

You also have to take into account the extent to which US capital markets is an export of services, eg advising foreign M&A, intermediating foreign investment eg listing Chinese stocks. And that a lot of financial activity is of dubious value added eg listing of Chinese stocks, fleecing retail and municipalities. And if you measure cost of the financial sector v. assets, you get a very different number at a market bottom and a market top.

Found the link. How much one could make borrowing at Fed Funds and lending to corporates doesn’t seem like a great measure of the unit costs of the financial sector.

Much of the efficiency in Finance seems to have resulted effectively in an increased velocity of money, which really doesn’t matter if the Fed cancels the inflationary effect by raising interest rates?

I surely appreciated this post since I would never have guessed that costs in financial intermediation have not come down these 30 years in the age of truly personal computers.

Yes. Increased intermediation costs are exactly what you would expect with parasites for every transaction in play.

As I keep saying: “It’s all about the rents!”

Very fun read

it’s hard to protect people from themselves. Seems to me IT costs are what’s really gone up.

In the old days all you needed was a 1) big black dial telephone, 2) a TV with tin foil on the antenna and 3) a record player. And you were good to go in any recreational or social situation. If the TV didn’t work right, you just whacked it with the side of your hand until it did. If you needed a job, you used the postal service to send out a letter if the help wanted ads didn’t work.

Now, you need broadband internet, a smart phone, a laptop, an iPad, and backup systems in case you lose something at the beach, and it’s still a wind sprint to keep up. If you’re working age and want a job, lots of this is not optional. You’re talking a few thousand dollars up front and hundreds of dollars a month, just to “stay connected”.

You can resist the financial innovation if you have self-discipline (I have a friend who, to this day, has never used an ATM), but you can’t resist the technological innovation unless you want to be a martyr.

The rise in spreads is probably driven by electrical and computer programming technology. You can trade so quickly you don’t need to worry what you pay ’cause you can always change your mind in 20 miliseconds. Maybe that’s an example of the “intertemporal price utility arbitrage gradient”. This is an equation of the form y=x^1.34 where x>0 .. It’s worse than digital cameras. You can take 100 pictures in 5 minutes and they’re all terrible. But one person who knows what they’re doing can take one picture per hour and it can be good, even using film and a Fuji Quicksnap purchased at the gas station.

econamic inefficency? Thats like saying burglary is income inefficency. What you mean is fraud leads to economic inefficency, scams lead to economic inefficency, dishonesty leads to economic inefficency, criminal mis rerpresentation leads to economic inefficency, lieing leads to economic inefficency. Only integrety leads to economic efficency. Economic inefficency is the symptom, a lack of ethics is the problem. The language used is dishonest and perpetuates the problem.