Journalists and laypeople tend to use stock markets at their proxy for economic and financial market conditions. The performance of US stock markets looked like an encouraging return to a semblance of normalcy after last week’s squall, until a wave of selling in the final hour, with 600 million shares of volume, pushed the major indexes solidly into negative territory. As of this writing, that barometer is still a bit wobbly. Australia was down 1.26% overnight and the Nikkei off .17%. But Chinese and the Singapore markets are up, as are European and the S&P and DJIA indices.

But some of the explanations are less persuasive than others. If you’d been paying even a little bit of attention the financial markets in 2012 and a chunk of 2013 were moving in lockstep, in a “risk on-risk off” pattern, with high yielding emerging markets as the preferred “risk on” trade. Hyun Song Shin of the San Francisco Fed took note of bond investor driven liquidity in a November 2013 presentation, stressing that the key theme was “search for yield” (in other words, a response to central bank negative real yields):

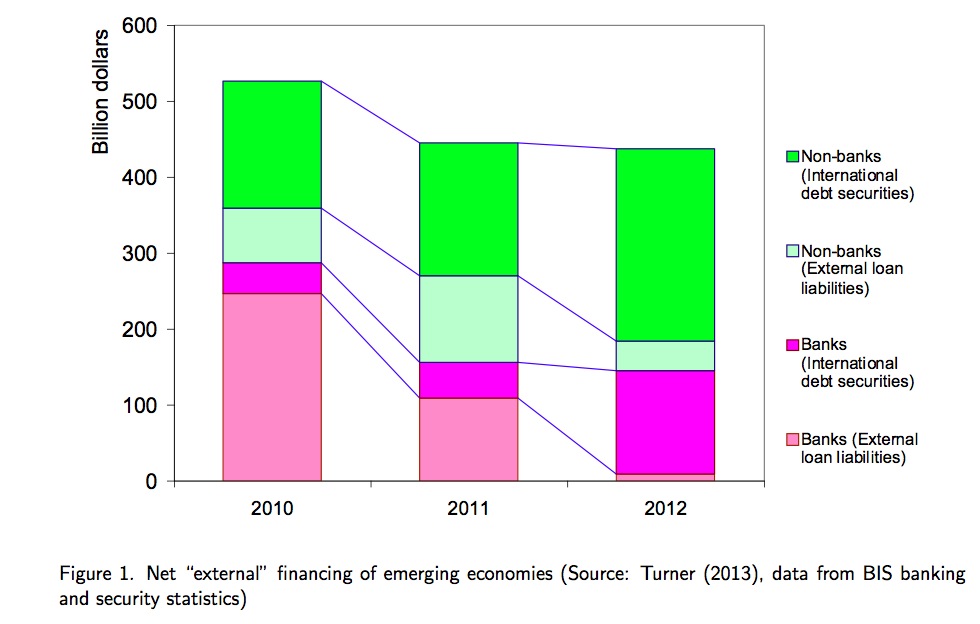

He anticipated more whackage to emerging markets, particularly since some had meaningful private sector borrowings in foreign currencies:

Impact on Emerging Economies

• EME local currency bond yields— have fallen in tandem with advanced economy bond yields

— have begun to move in lock-step with advanced economy bond yields

• Explosion of EME corporate bond issuance activity, especially offshore

issuance— Implications for domestic monetary aggregates and potential for runs of wholesale deposits

— Currency mismatch on consolidated corporate balance sheets• Transmission channel is reinforced by exchange rate changes

Likely Elements in Crisis Dynamics1. Sharp steepening of local currency yield curve

2. Currency depreciation, corporate distress, freeze in corporate CAPEX, slowdown in growth

3. Runs of wholesale corporate deposits from domestic banking sector

4. Asset managers cut back positions in EME corporate bonds citing slower growth in EMEs

5. Back to Step 1, and repeat…

In various analyst comments on the crisis, there’s been a tendency to blame some, even most, of the emerging countries for “living beyond their means”. That must strike many officials in these economies as offensive, since the BRICs and some smaller countries complained to the Fed about the destabilizing effects of QE-driven hot money coming into their economies, as well as goosing commodity prices. The Fed ignored their pleas. As Paul Tucker, recently deputy governor of the Bank of England, pointed out in a speech last week (had tip RA):

Time and again policymakers have had to be reminded that gross capital flows matter as well as net flows. In the 1990s Asian crisis, the sectors under pressure varied according to who had borrowed short term in foreign currencies in external markets. In Thailand, it was the government; in Korea, the banks; but in Indonesia, the nonfinancial corporate sector. The rapid withdrawal of hot money triggered combined liquidity and exchange-rate-regime crises. In a nutshell, lessons included the importance of developing domestic capital markets, so that local savers and borrowers could meet without the currency transformation entailed by international- market intermediation; the virtues of floating exchange rates; and the importance of monitoring and managing national balance sheets. The latter was the central theme of one the key official sector reports to ministers (the ‘Draghi Committee Report’)5. Some EMEs took it to heart, accumulating fx reserves to build a “fortress balance sheet”, and thereby self-insuring against shocks rather than relying on external insurance from the IMF…

The trials of both the Asian EMEs in the 1990s and the EA more recently are examples of capital flight exacerbating a homegrown problem. But capital does not flee solely due to crisis in recipient countries. The problems might begin in the providing country(ies), with capital pulled back home to help sort out problems there or simply to reduce activity away from a lender’s core-franchise markets. This has been a potent channel of contagion during the recent crisis. An example would be Euro Area banks abruptly pulling out of trade finance in Southeast Asia in 2011/12. Thus, an excess of flighty liabilities can be a source of vulnerability even if domestic economic fundamentals are broadly sound.

Arguably most frustrating for recipients, the initial flight of capital needn’t be prompted by a crisis anywhere at all. It might simply be a ‘rotation’ of short-term capital from one set of opportunities to others elsewhere: game over, move on. That has come to the fore over the past few years as short-term capital first poured in to a number of EMEs — pushing up exchange rates and asset values, and loosening internal credit conditions; then withdrew; and most recently returned. EME financial conditions deteriorated abruptly in the middle of last year when it looked as though the Fed would begin to ‘taper’— ie slow the pace of expansion of — its monetary stimulus. Perversely, EMEs that had nurtured reasonably liquid domestic capital markets were amongst the worst hit, as entry had been easier; this fits with talk of ‘proxy hedging’ in broadly correlated, more liquid markets in earlier episodes.

In other words, the best students of the Washington Consensus got punished the most.

Even though the the Fed’s taper talk sent a shudder through emerging markets last year, at least as big a culprit has been slowing growth in China, since lower demand for commodities hits many smaller economies hard (for instance, falling soyabean and corn prices have hurt Argentina’s foreign exchange position, greatly increasing its vulnerability). We’ve been skeptics of the “soft landing” consensus, because China is trying to engineer a transition from an export/investment driven economy to a consumer oriented one, and no country has managed that transition smoothly. Even worse, China’s consumption share of GDP has generally been declining in recent years.

A comment at the Financial Times by Ruchir Sharma, Morgan Stanley’s head of emerging markets and global macro, argues that the Chinese credit boom is likely to come to a nasty end. Key bits of this important piece:

Recent studies have isolated the most reliable signal of a looming financial crisis and it is the “credit gap”, or the increase in private sector credit as a proportion of economic output over the most recent five-year period. In China, that gap has risen since 2008 by a stunning 71 percentage points, taking total debt to about 230 per cent of gross domestic product…

Looking back over the past 50 years and focusing on the most extreme credit booms – the top 0.5 per cent – turns up 33 cases, with a minimum credit gap of 42 percentage points.

Of these nations, 22 suffered a credit crisis in the subsequent five years and all suffered an economic slowdown. On average, the annual economic growth rate fell from 5.2 per cent to 1.8 per cent. Not one country got away without facing either a crisis or a major economic slowdown. Thailand, Malaysia, Chile, Zimbabwe and Latvia have had a gap higher than 60 points. All those binges ended in a severe credit crisis…

China has hit its ambitious growth targets so consistently that many analysts can no longer imagine a miss. The consensus forecast is for growth of 7.5 per cent this year, right on target. Growth is widely expected to continue at an average rate of 6-7 per cent for the next five years. It is hard to find a prominent economist who forecasts a significant slowdown, much less a credit crisis…

History foretells a different story. In the 33 cases in which countries built up extreme credit gaps, the pace of GDP growth more than halved subsequently. If China follows that path, its growth rate over the next five years would average between 4 per cent and 5 per cent.

The key to foretelling credit trouble is not the size but the pace of growth in debt, because during rapid credit booms more and more loans go to wasteful endeavours. That is China today…

Those who trust in China’s exceptionalism say it has special defences. It has a war chest of foreign exchange reserves and a current account surplus, reducing its dependence on foreign capital flows. Its banks are supported by large domestic savings, and enjoy low loan-to-deposit ratios…

These defences have failed before. Taiwan suffered a banking crisis in 1995, despite having foreign exchange reserves that totalled 45 per cent of GDP, a slightly higher level than China has today. Taiwan’s banks also enjoyed low loan-to-deposit ratios, but that did not avert a credit crunch. Banking crises also hit Japan in the 1970s and Malaysia in the 1990s, even though these countries had savings rates of about 40 per cent of GDP.

And notice the message sent by the US markets. The S&P, which has the heaviest exposure to banks, has been the most sensitive to the EM tremors. Remember that Lehman, which had a large emerging markets desk, nearly went bust in the 1997 Asian markets crisis. Our big banks now look better diversified, but if a large bank wrong-footed enough trades, it could take a meaningful hit to its balance sheet. And more weakly capitalized Eurobanks are less able to sustain this sort of blow well. So while the emerging markets wobbles may not evolve into a full-blown crisis, it’s likely we’ll have a sustained period of rockiness before conditions stabilize, and with deflationary pressures on, they could well resolve at markedly lower prices for risk assets than we see now.

I think this whole episode demonstrates the scale and risks of worldwide speculation.

This huge speculation is the result of too much capital and too little purchasing power.

The income problem was masked by growing credit, until this expoded in 2008.

There are no good investment opportunities in the real economy, so speculation is the answer.

QE resulted in free money for big players. They used it for even more speculation.

A large part of this money-on-credit flowed into EM’s, causing significant bubbles and inflation in those countries. But this leveraged carry-trade has the potential of huge profits (interest, exchange rate effects en bubble-forming). But also of huge losses when conditions reverse.

Too much capital=speculation, speculation=instability.

As good an analysis of short term capital movements as I have ever read. I would put it slightly differently: trends continue until they end. What financial writers simply ignore is the reality of ‘excess capital’, which is not really capital (a real thing) but accumulated financial profits, a dead hand out of the past, which sloshes around in the real world seeking something for nothing, endlessly, plunging first into this, then into that, stimulating production at first, but ultimately creating speculative bubbles in this or that asset, and finally migrating elsewhere, leaving real carnage behind. Believe it or not, there exists an actual class of real people who benefit endlessly from this fandango; their gain is your loss, and yours and yours and yours, although you or you or you can perhaps enjoy some (temporary) prosperity if you move fast enough yourself, or are lucky enough, which really amounts to the same thing.

If anybody really understood how this works he would have more money that Soros, Buffet, etc. I suppose they understand it well enough, right?

I have suspected for a while that there is a direct relationship between inequality, capital concentration, and global economic instability. There are huge pools of money chasing yield and if cannot be had it may be artificially created. Invariably it is a result of a number of factors 1) tax advantages for capital gains, 2) low interest rates / currency carry trade 3) positive reinforcement between goosed asset prices and additional speculation (ex. oil prices, oligarchs, and sovereign wealth funds), 4) increasingly financialized large institutions (ex. endowments, pensions) seeking yield through alternative investments promoted by financial ‘advisors’ 5) increasing inequality due to rewards from productivity gains being concentrated in the hands of a few (market short-termism/profit maximization) 6) deregulation of a wide variety of financial products and investment mechanisms 7) financial institutions laundering black money 8) global tax avoidance by corporations and high net worth individuals 9) increasingly concentrated myopic tribe / cult making financial decisions, 10) government / regulatory capture and control

These factors and I am sure some others become self-reinforcing, you get positive feedback loops, and recurrent bubble conditions.

It really wouldn’t be so bad if it was just rich people losing their own money. But, somehow they also manage to convince or coerce the poor schleps on the streets or the gullible managers of their money to play hot potato. This usually happens towards the end of the game when everyone with a modicum of understanding has gotten out of the game. Then they convince the government to clean up their mess.

Is there some point at which the economists start to realize that the whole economy is, without drastic intervention, hopelessly addicted to fossil fuels — and so without a vast withdrawal from fossil fuel consumption we can expect vast reductions in the human population of planet Earth due to catastrophic changes in climate?

Or are we still on the level of “omigod profits” after four decades of declining global growth so keep playing those financial Ponzi schemes?

When will it become accepted that the western capitalist system is, at its core, a Ponzi scheme requiring ever larger investments to realize continuing profits?

Even Dr Hawkings has revised his thinking on Black Holes!

Black hole economics – I like it. Sums everything up quite nicely.

Yves-

Re: peacefully transitioning from an investment-based to a consumption-based economy.

Didn’t Europe manage to do this? They were the emerging market economies of the post-war era, using Marshall Plan investments to rapidly rebuild their infrastructure, then converted to consumption-based economies relatively smoothly. I’m not an economic historian so I’m curious whether my take on Europe is correct, and what lessons that might hold for China.

There’s only one way

If you’re one of these guys, one of these guys who spouts this stuff and gets quoted in the paper — you’ve already found a way to monetize nonsense.

You don’t need your nonsense to be correct, or even rational. It doesn’t even need to be lucid. It, frankly, can be completely incoherent. Who’d be able to tell? Nobody really. Who would care? If nobody can tell, nobody would care. So nobody.

You can start in the middle and read up. Or start at the top and read down to the middle. Or start at the bottom and read up. It doesn’t matter. The meaning isn’t in the words, it’s in the signs of erudition and those are as logical as flowers but not nearly as beautiful.

There’s only one way to make big bucks spouting this stuff for a job — sucking down a big salary leveraging beta and then getting the Fed Bailout when the fan is hit by all your little prolix pedantic petals of presumptive pomposity.

but God Forbid you try to actually make money on your nonsense with just a little capital and your fingers crossed hoping for a lucky trade, and you’ll discover what “capital flight” really means. hahahah. You will. Just take $100 grand and try it.

Dead solid perfect!

I note that Stephen Roach, the previous Asia-desk man for Morgan Stanley is also concerned re China – and with good reason, as Yves’ piece amply demonstrates.

I think the ramifications of a slowing China facing a hostile US, a Russia now similarly demonized, emerging markets’ history of being ignored as if permanent creatures of “the developing world” and the pre-existing depth of the malaise in the West have for the US go well beyond the major stock market correction that is cooked in sometime over the next 18 months.

The inability of the core global economy, the US, to exercise anything resembling positive leadership, ending again in financial turmoil is not going to sit well elsewhere. A lot of the world has been struggling mightily just to cope with the effects of the last bust, in addition to those emerging markets so distorted by QE policy. Global confidence in the basic US ability to “manage” the global economy is going to take another big hit. This will in turn generate greater divisions and tensions as it becomes increasingly evident that corporate capitalism, US 21st century global style, in fact fails to support either itself or most of people who struggle under its aegis.

Six years straight down the tubes and another 8 before that in terms of dismal global leadership – I don’t think the BRICS et al or the American public will tolerate another 6 years of governance this rank. It’s only a question of whether it lands on Obama’s watch, and I don’t see any reason to rule it out.

Then watch, Warren Buffet and Jamie Dimon call for Obama to stay on another term, as he’s ideally suited for the job.

Did you see the Alibaba results given in Yahoo’s earnings today? It might give an insight into the health of the Chinese economy.

I have a “de-banked” portfolio consisting of non-financial companies. (There are a few financial-entangled conglomerates, but for the most part I’ve gotten rid of all financial companies.)

I’m expecting this to hold up better in the next crash than the big averages. There’s only so many times banks will be bailed out, and they’re fragile.

Update: Jan. 29th, 2:26 pm est.

Appears the EM respite was for 1 day only – Dow currently off 200+ pts. Would like to point out that Turkey is taking a beating, which is not at all good given its involvement with the crisis in Syria. Erdogan was a fool to get suckered in by the US on that one.