By Dan Kervick, who does research in decision theory and analytic metaphysics. Cross posted from New Economic Perspectives

Everybody is very excited about Thomas Piketty’s new book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, whose English translation is due out on March 10th from Harvard University Press. The book studies long term trends in the accumulation and concentration of wealth, and in the evolution of inequality. The argument of the book is intensely data-driven, and has been billed as a game changer since it first appeared in French earlier this year.

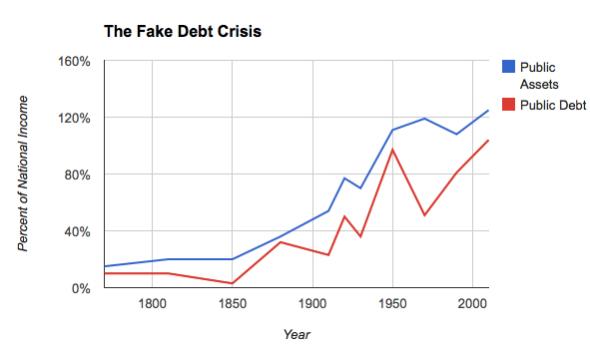

Matt Yglesias reproduces a chart from the book, and calls it “the chart the debt alarmists don’t want you to see”. However, if I were a debt alarmist, I don’t think I would be very much moved by the chart, and wouldn’t worry so much about others seeing it. Let me explain. Here is Piketty’s original version of the chart, and here is Yglesias’s colorized reproduction :

“Public assets” in Piketty’s usage denotes all of a government’s fixed assets, financial assets and land. Interestingly, Piketty excludes such non-produced assets as “energy and mineral resources, timber, spectrum rights, and the like” in his calculations of public assets.

So what the chart shows, assuming Piketty’s numbers are accurate, is that the United States is solvent in the sense that its public assets exceed its public debt liabilities. But even the debt alarmists know that the US government possesses a great deal of land and fixed capital wealth. What they seem to argue, though, is that we are on a fiscal path that will lead to higher borrowing costs and debt service payments, and either to greater real tax burdens or to ultimate dollar devaluation as we monetize and inflate away some of the debt.

There are very good responses that can be made to counter these fears, but I don’t think appealing to the value of US fixed assets and land is one of them. If progressives respond to the debt alarmist arguments only by arguing that the US government has positive real net worth, and can always pay its debt by selling off Yellowstone, the Executive Office Building or the USS Nimitz, they have clearly lost the political argument. Even the Greeks have valuable properties like the Acropolis to sell if they run into further sovereign debt crises, and are determined to stay with their crippling commitment to the Euro. But nobody would find that to be a reassuring point. The focus in countering the debt worriers should be on economic sustainability arguments that do not depend on the ultimate capacity of government to liquidate its fixed and real public wealth in a fire sale.

(Personally, I think the US government should be accumulating more public wealth, and commanding more of the nation’s capital as part of a commitment to an expanded strategic direction-setting role, with a new activist determination to drive innovation and structural transformation through mission-driven public investment. But that’s an argument for another time.)

I will be curious to read more in depth about how Piketty measures public financial assets. But for a country that produces its own currency, its financial assets are effectively infinite in nominal terms. Obviously, that doesn’t mean that producing unlimited quantities of currency would be sound policy. But it does mean that such a government has financial resources that far exceed the market value of the money and money-denominated assets it happens to have in its current possession. That is especially the case now in the US and other western societies, where stagnating, high unemployment economies should be able to power a surge in public spending though expanded net private sector holdings of currency and currency-denominated government financial assets. Given how far these economies are from reaching their underlying economic capacity, they should be able to do this without producing significant inflation.

The very concept of “capital” takes on a different tone and shape when applied to national governments as opposed to private firms. The financial capital of a currency-issuing government does not really consist in the existing units of the currency that the government has in its possession, but in the whole collection of tangible and intangible assets that permit a government to continue to issue those units of currency, and to have them accepted in exchange for goods and services the government wishes to acquire from the private sector on behalf of the public to pursue public purposes. Those assets don’t just consist in the physical and operational infrastructure the government uses to run its monetary system, but include all of the foundations of the government’s power, authority and reputation. It really makes little sense to try to measure a government’s financial capacity by adding up the notes, bills, bonds and electronic account balances it happens to hold in its possession at any given time.

If the US really has a debt crisis, which I also doubt, a logical response would be to tax away the unearned wealth of those who have been looting our banks and public corporations for the past thirty odd years. And I see no reason for waiting until they die, either. How about a 95% net wealth tax on assets above 100 million? I would love to hear someone explain why he needs more than that. About the only reason I can think of is for corrupting the political process.

The irony is that those that bellyache about the public debt are also those most firmly believe in trickle down economics.

Not only corrupting the political process. They like or need to demonstrate that they are rich and belong to a different class. To justify your wealth you need also be arrogant and eliminate any legal (taxes) or illegal access for the ordinary people to your wealth. They spend a lot to protect their assets.

“…access to your wealth.”

Individual ownership is a legal fiction. Wealth is a gift of nature and the work of all of society, past and present. Property is theft. You can’t say that enough.

These are separate issues. The bottom line is that the U.S. government doesn’t need taxes to fund its spending. The U.S. government can create any amount of dollars at any time, limited only by the inflation that would occur if it did so beyond the capacity of the U.S. economy to provide additional goods and services. We are nowhere near the point where creating dollars would cause inflation. If the U.S. government chooses to tax in order to change the distribution of wealth that is a political decision that has nothing to do with its ability to spend.

From a grumpy old man-in-training

“Obviously, that doesn’t mean that producing unlimited quantities of currency would be sound policy.”

Okay, I’ll bite. Why is producing unlimited quantities of currency a bad thing? In detail. For the USA. In the year of our lord 2014? (not the USA in 1780s, not Germany in the 1930s, not Zimbabwe now).

Okay, I guess rhetorical phrases, like “the US deficit” deserve rhetorical answers, like “producing unlimited quantities of money”.

But let me add that I agree with the post. The “debt crisis” is real, but not the one being promoted by the MSM.

You must not have been around in the 1970s. To get moderate inflation, you need people to be worried enough about price increases to that they inventory stuff. They buy anything that is storable pronto because they are aware that their currency is depreciating. But even more important is wage escalation, that workers demand pay increases to compensate for their loss of purchasing power. Do you see even an iota of wage inflation in the US? Wages, BTW, are the single biggest component of product costs for pretty much any product (and I don’t mean factory wages, I mean all wages, like factory labor, factory supervision, marketing, general administration, R&D….and the wage component of parts and materials purchased from suppliers).

And you really need to bone up on hyperinflation. It takes very specific conditions to create it, namely, destruction of a very large amount of the country’s productive capacity.

Inflation in the Seventies was not wage driven. The price of oil increased five fold between 1969 and 1980. Speculation did the rest. Labor is always making demands, but corporations accede only when they can push along price increases that increase profits. The speculation was fueled by bank lending which Volker brought to a screaming halt in 1981. The big banks were insolvent due to sovereign lending, with the biggest debtor being Mexico. Mexico acceded to austerity and the price of oil magically began dropping. The whole thing was orchestrated.

I really need to take Galbraith’s comment about his writing style to heart – to paraphrase my faulty recollection, Galbraith said it took him 6 rewrites to get that spontaneous, breezy style beloved by his readers (I only took 3 rewrites to get my not very clear reply).

First, I do remember the seventies; COLA, and slogans of WIN from Ford, and buying an item today because next week the price would go up. And I remember the vague, muttered economic answer as to why prices were going up, “Too much money chasing too few dollars…” which even at the dawn of my political and economic naivety seemed a bit off.

My posting meant to strike at the difference between giving credit to someone and giving dollars to someone. The TARP, et.al,, bail outs of 2008 were a failure in producing a demand for consumer goods because the credit went to the banks, with the “expectation” that the banks would pass on the money to the consumers. If only one tenth of that money was spent in a direct check being sent to each household in the States, consumer demand would have gone up sharply. And demand drives the economy, not the supply.

Now, would inflation have been rekindled? Who knows? I’m not convince that the mechanisms that causes inflation are well and truly known. j gibbs’ posting March 1, 2014 at 8:53pm is a nice summary of the probable causes of the 1970s inflation, but I will say, as one who was there, with my COLA, that many people, then and now, think that wages drove that inflation machine.

The simple solution to most of USA’s problems is rent extraction. One of the better examples is the quality of the internet in the USA vs the rest of the world’s industlized nations. We need to rescind there license’s for failure to meet agreement of conditions that gave these licenses in 1996 congress.

Re: Yglesias

Why oh why does this guy get taken seriously as an economic analyst (Y, I mean, not Kervick)? He only has a bachelor’s degree for f— sake, he doesn’t appear to have done much of any work in the real world, he writes obvious nonsense most of the time (other times it’s thinly-disguised nonsense), and clearly he has a sense of self-importance out of all proportion with the facts. Sometimes I feel like even acknowledging his existence is just encouraging him. In future, I suggest referring to him not by name, since he no doubt gets a charge out of that, but rather as “a certain prematurely bald, and woefully under-qualified economics pundit.”

Well, whether deserved or not, his blog is one of the most widely read ones out there among the blogs broadly focused on economics, so I think it is important to counter arguments he makes when they misfire. In this case, I was glad he was taking on the debt worriers, but concerned about the line of argument he was using.

One thing he says, relying on that chart, is that “on a net basis the United States of America does not have any public debt and perhaps never did.” That’s a strange way of putting it. On that account, the only entities that “have debt” are those that are literally insolvent. But I think we all understand that, where businesses and households are concerned, a debt burden can be oppressive, dangerous and uneconomical, even if that household or business is not literally bankrupt. If I told my wife, “Hey, no reason to worry about our household debt because we are still net solvent and we can always sell our house, clothes, appliances, books and cars to pay it off,” she would rightly think I was nuts.

So I think people who are trying to fight off the Fix the Debt crowd and others would do better to focus on the ways the US government is not like a household or firm.

Also, one thing I didn’t point out in the piece, but probably should in another piece, is that the economic policy of the US government should not be measured according to whether the government is making itself richer or poorer. A government is not an enterprise like a private business whose goal is to increase its own wealth. It is an enterprise whose purpose is to increase the overall well-being of the society of which it is the government. That might in some cases be accomplished with a net decrease in the government’s own wealth.

This is a good point: public capital is not the same as private capital. Confusing since the currency they share is based on “public capital” – even tho’ private capital pirates that very money for its own exclusive purposes (profit seeking) and hoards it away. Go figure. So since public capital is the real capital upon which the economy is based and in fact creates and controls all possible markets except black ones, the government should “issue currency in exchange for goods and services it wishes to acquire from the private sector on behalf of the public to pursue public purposes.” End of argument, except that the debt freaks think it is “their” money. It’s Stephanie Kelton’s demo all over again – before the government can pursue public purposes it must issue money, create a functioning economy and then tax for operating revenue. The whole argument about inflation (debt here) never looks at the private sector as the culprit, only the government. But clearly that is nonsense because when the government goes austerity (beginning with Clinton) it forces the private sector to inflate just to stay alive. And that inflation does not have a public purpose and quickly gets out of control. I hope Janet Yellen and other economists have learned something about the value of public debt because she/they were big boosters of Clinton’s balanced budget in the 90s. Which was a huge mistake.

Surely Susan, austerity unleashes entrepreneurial forces, prevents governments misallocating capital and lets markets function to provide what we need. This is how it works on Zog, the planet only economists and the rich are allowed to visit.

I don’t know anyone who takes him seriously. I don’t even recognize his name.

give us all a break already. an advanced degree in astrophysics might mean something (even though Einstein and Tesla figured it out in a library) but economics? puh leeze

It’s more like a dark hood over the head, an eyeless impediment to the achievement of clarity.

Otherwise, I have no clue who this guy is or why anybody would want to read what he writes down. Has he ever written down anything that somebody reads and says “Hmmm. How about that? It’s not bad. Maybe I’ll read another paragraph just to make sure he didn’t get lucky.” I have no idea. Maybe. But anyway, who cares when there’s Youtube?

Yglesias was one of my favorite Dem pundit blatherers to hypothesize whether he was bought and paid for or an honest fool. I don’t read him much anymore, but when I did, he was especially vigorous in his defense of the silly notion that powerful people should be above the law.

From the WayBack Machine, here’s one of Yglesias’ classic lines: “…anxiety-producing fraud prosecutions…”

Makes me laugh just thinking about it.

http://thinkprogress.org/yglesias/2011/04/14/200593/the-fraud-free-financial-crisis/#

I’m not sure why this little post has gotten so much negative response here. Of course much depends on how you determine the value of “public assets” but I believe the general idea makes sense to me. But then I believe that the ONLY reason that the whole “debt crisis” exists is in order, to be blunt, to eliminate all non-military non-corporate welfare spending.

Not too long ago when interest rates were higher, the federal government was on track to pay almost 20% of its ENTIRE federal budget as debt payments. These payments are often collected by imposing regressive taxes on working people. In contrast, the interest is most often paid to the wealthiest families, foundations, corporations and other so-called 5%ers. If these tax dollars weren’t being paid to the wealthy 5%ers as interest, they could be spent on critical government programs or used to reduce other regressive taxes. Why anyone thinks making debt payments to the wealthy 5%ers is a good thing has always boggled the mind.

Apart from emergencies such as wars or weather related calamities, the ever-insatiable need for government debt seems designed mostly to empower and enrich Wall Street (lots of highly paid lawyers and financiers involved with debt issuance), reward powerful and wealthy bondholders and constrain government in its ability to solve real economic problems.

As far as the supposed need to issue debt to “create” jobs, this rational is a non-sequitur. Humans have always used ingenuity and innovation to drive technological improvements that reduce the need for labor. This is a good thing since it frees up time for other productive and/or non-productive activities. In times of rapid technological changes such as we’re experiencing, a better policy is to reduce the work-week to absorb the temporally dislocated workers. Small businesses and the self-employed can be exempted from shorter work-week requirements, but in large organizations there is plenty of work to go around that can be easily shared. A shorter work-week not only absorbs un- and under-employed workers, but it helps increase salaries and wages for everyone as businesses compete for a much smaller labor pool.

In response to other articles posted on NC, some posters have made excellent comments focusing on the need for tax reform and job-sharing strategies. These are the issues of our time, not issuing more debt. For decades the US and other developed countries have tried “liberal” economic policies favoring debt expansion, transfer payments (food stamps, unemployment benefits, etc.), transportation projects and other government initiatives to try to “turn the economy around.” None have worked, yet the debts keep getting larger, the cost of living keeps getting higher, and the economic problems become more intractable.

To the extent the goal is to raise the standard of living of the bottom 2/3 of society, a short list of effective changes would be:

1) Repealing regressive payroll and sales taxes, replacing them with higher graduated tax rates on the highest incomes from passive sources (rents, interest, dividends, royalties, capital gains, etc.), and a graduated wealth tax starting at 5% above $10 million, rising to 35% on amounts above $100 million;

2) Eliminating government debt, using the taxes enumerated above;

3) Reducing the work-week to 4 days maximum for any company larger than 1,000 or 5,000 employees. If unemployment remains above 4%, reduce the work-week further.

4) Implementing a 65-90% capital gains tax on all residential and commercial property sales other than a primary personal residence.

None of these items are particularly radical or unconstitutional, but they would deliver the most benefit to lower and middle income working people. Employment would go up dramatically, wages would go up, disposable income would go up (from eliminating regressive taxes notwithstanding a shorter work-week), and housing costs would go down as property speculators fled the real estate market. And with zero government debt payments, there would be more money to spend on necessary government programs and services.

Not bad, but I disagree about income taxes. What we need is a tax on land qua land (not improvements) and a tax on egregious accumulations of wealth. Income taxes are always regressive in practice. You have a one page rate schedule and 7,000 pages of loopholes. The lowest rates absorb all the savings of the bottom income earners, which is exactly what they are designed to do. Income taxes are what keep the poor poor and the rich rich.

There certainly is something to be said for finding alternatives that could be done within the existing public mindset as regards public debt vs MMT-like solutions premised on infinite ability for government to issue debt, spend money into existence on projects, and similar notions just as a practical political matter. The 4-day work week, and similar measures for professions where desirable or required, would not just employ more people, lower stress (big positive for health) and provide more leisure time, but that extra time created will have potential demands to be met.

(Personally, I think the US government should be accumulating more public wealth, and commanding more of the nation’s capital as part of a commitment to an expanded strategic direction-setting role, with a new activist determination to drive innovation and structural transformation through mission-driven public investment. But that’s an argument for another time.)

Now that would be interesting Dan, given it’s just what our bought and paid for politics and vaunted entrepreneurial sector claim to be achieving as their reason for being. Debt has multiple meanings if we examine it in use, including those raised through exclusions in what is put forward as quantitative presentation.

Our current system is incredibly broken to the extent we can’t see that debt is more and more to do (again) with indenture, something we should want people to be free of. We draft ideas on such as freedom of information and micro finance only for them to collapse to nightmare in practice. We went ‘global’ only to discover this made matters much worse for almost all of us. The difference between public and private debt seems largely one of asset ownership to me. Our share of public debt gives us ownership of a kind and private debt (including what is looted) indentures us through economic rent, often paid because we are left with the bill after very private looting.

Beyond this, one might imagine the USA levelled much as Germany or Japan after WW2 – beyond any insurance capacity. Who then owns the rubble or the debts the pre-rubble buildings were the assets of? Where does the money, material and labour to rebuild come from, as we surely would? No ‘small’ thought experiment in economics this. I’d guess most people in the US would be better off after this disaster than now, so why can’t we achieve it without the disaster? Moral hazard? What might we build if citizens were free of much current debt and what of debt is defined by our inability to build much that makes environmental and quality of life sense?

The moral hazard component of debt is socially constructed and can be unmade, admittedly not without problems, but loans were made in the past as a bet on whether a ruler lived or died. I don’t want a return to this, yet thinking of moral hazard in another way, wouldn’t a lending and borrowing system be very different under the possibility of a jubilee call?

read somewhere that under the jubilees of ancient times a creditor who got stiffed was not obligated to loan you money again, kinda like a credit rating agency… but you could go it alone without the burden of debt if it was killing you. So still a win, win.

… “commanding more of the nation’s capital as part of a commitment to an expanded strategic direction-setting role, with a new activist determination to drive innovation and structural transformation through mission-driven public investment. But that’s an argument for another time.”

I look forward to that public conversation regarding structural reforms very much, Dan. We have seen enough of their failed policies over the past three decades. Thank you for this post.

Given that debts are really enforced by ability to send the boys round, I’m not sure whether jubilees would have been 100%. Piketty seems to argue the rich get richer when our economies grow slowly. I suspect deeper, biological-libidinal forces.

Piketty’s work can be found summarised here:

http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21592635-revisiting-old-argument-about-impact-capitalism-all-men-are-created

The government doesn’t cash in capital to pay debts. What’s important to paying government debt are the ability to rollover debt and the interest on the debt. Neither item is a problem for the U.S. government

Yglesias’ post is a distraction, painting things as red team vs. blue team (debt alarmists vs serious people).

Debt is a long term issue if it grows to be large enough in aggregate size, but the short-term issue isn’t whether it is more or less than public assets. I mean, think about this conceptually – most public assets are not liquid in any remotely good scenario. What is relevant is whether resources represented by that debt have been invested wisely or squandered wastefully.

Furthermore, one of the primary weapons against inequality is raising taxes on the wealthy. That this also would reduce the debt is not a bad thing; it’s actually a nice side benefit. Indeed, the two are intimately related – printing lots of currency (net deficit spending) while stagnating worker wages is the prime mechanism of how the looting has worked over the past couple decades. If debt didn’t pay for the all the corporate welfare, it would just be a transfer from wealthy people to wealthy people, defeating the whole point.