By Frances Coppola. Originally published at Coppola Comment

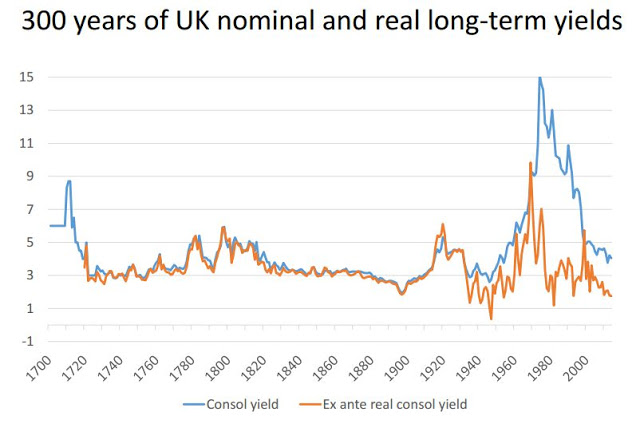

When a former Bank of England deputy governor gives a presentation entitled “Are Low Interest Rates Natural?” to a extraordinarily high-powered audience of academics and monetary policymakers, you can bet he will come up with some great charts. Charlie Bean’s historical analysis of long-term real and nominal yields in the UK is amazing:

It is very evident that for most of the last 200 years, nominal and real consol yields have been pretty much pinned together. Charlie said that the gold standard prevented rates deviating by keeping the price level under control. But I am unconvinced by this.

Firstly, let’s look at the historical record. In 1717, Isaac Newton, then Master of the Mint, changed from defining the value of the pound in silver as had traditionally been the case to defining it in gold. At that time, most banknotes were issued by commercial banks: the Bank of England issued notes in return for deposits, but for high denominations only and the amounts were variable. After the Bank Charter Act of 1844, which ended the issuance of banknotes by commercial banks in England and Wales (though not in Scotland or Northern Ireland), the Bank of England gradually moved to issuing notes for fixed amounts and lower denominations. But for much of the century, banknotes were issued in high denominations only and were not widely used, except in Scotland where a £1 note was popular (as it still is today). Most people used coins for everyday transactions, principally small-denomination silver coins. For all practical purposes, therefore, what Britain actually had during this time was bimetallism, rather than a gold standard as we would understand it now.

But no matter. War destroys gold standards, whether bimetallic or paper. Even though the gold standard only really applied to high-denomination bank notes, not the common currency used by the people of Britain, when Britain went to war with France in 1793, gold convertibility came under increased pressure as investors retreated into outright holdings of gold. The Bank of England eventually suspended gold convertibility in 1797 after a series of runs on the Bank threatened to drain its gold reserves. Convertibility was not restored until 1816 after the ending of hostilities with France.

And yet the fact that gold convertibility was abandoned for nearly twenty years barely creates a ripple on Charlie Bean’s chart. Both nominal and real rates rose, but in parallel with each other.

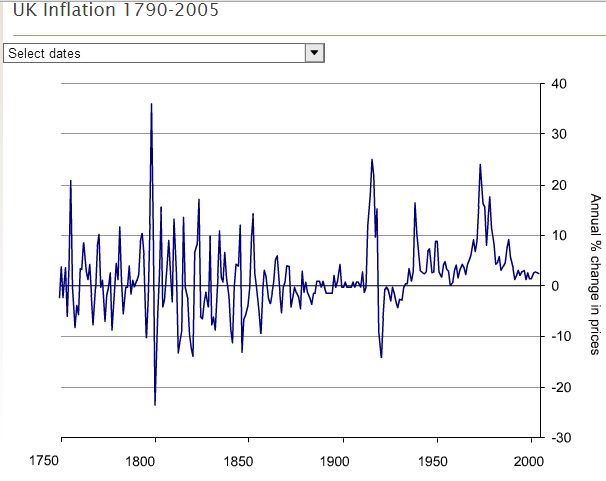

It also isn’t the case that prices were under control during this period. Inflation was very high – in 1800 it touched 36% – and volatile:

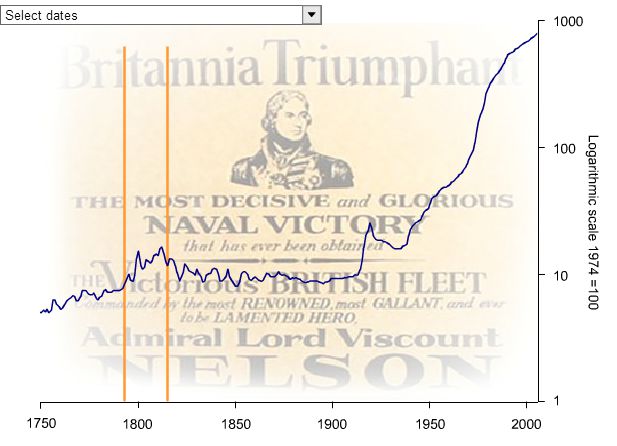

And the price level rose during this period:

(both charts from the Bank of England)

Price level rises are common during and after wars because of supply-side destruction coupled with very high government spending: the price level rise during and after World War I is also very evident on this chart. The price level rise is sufficient to explain rising yields during the French Wars. But it doesn’t explain why real and nominal yields didn’t diverge during a period of high inflation and suspended gold convertibility. There must have been some strong nominal anchor keeping them pinned together. It certainly wasn’t inflation targeting. Anyone hazard a guess as to what it was? I reckon it was a fixed exchange rate, but I could be wrong.

But the real story on this chart is, of course, the Great Divergence of real and nominal yields. Ever since the Great Depression, nominal yields have been persistently above real yields, often by a substantial margin. Even during Bretton Woods, a period of relative financial stability (and a quasi-gold standard), nominal yields were somewhat above real yields. Yet in the previous 200 years, despite periods of fiat currency and high inflation, real and nominal yields didn’t diverge. Why do they now?

This is not just an idle question. The yield on consols (interest-bearing government perpetuals) is a proxy for the risk-free rate of interest. If nominal yields are persistently above real yields even in the absence of significant inflation, then something is massively askew in the pricing of risk-free assets. Today, inflation is hovering around zero, but Charlie’s chart shows us that nominal yields are about two percentage points above real yields. I thought the post-crisis period was supposed to have euthanised rentiers? This chart suggests that they are doing better than ever.

Perhaps what this divergence tells us is that our expectations of future returns are persistently skewed to the upside. We therefore undervalue safe assets (hence high nominal yields) and overvalue risky ones. As Andy Harless says, safety is a scarce and valuable asset. Arguably, it should be a lot more expensive than it is. Perhaps we don’t really think it is necessary – or we don’t really think these assets are safe.

But why did everything change in the Depression? I don’t buy the gold standard argument. Rather, I think that the cataclysmic shocks of the 20th century have weirdly distorted our view of financial reality. The fact is that a significant proportion of the human race now expect to receive returns on financial assets that are far removed from the real ability of the economy to generate them. I don’t know why this is, but in my view we should be looking at things like labour market dynamics, longevity and pension expectations.

And we need to look at them as a matter of urgency. Such divergence between nominal and real rates suggests that there is a continual drain of resources from workers to rentiers, from young to old and from poor to rich. This shows itself as rising indebtedness among the young and poor, and increasing fragility of the global financial system. It cannot possibly be sustainable.

In his presentation, Charlie Bean reviewed an array of measures that might give central banks more control of nominal rates at the zero lower bound,such as raising the inflation target, negative rates and eliminating or charging interest on cash. But he concluded:

“It would be better to find ways of raising the natural rate through structural and fiscal policies.”

Indeed, somehow we have to bring nominal and real rates back together. Ideally this would be through raising the natural rate. But I suspect the post-Depression natural (real) rate is lower than we would like it to be, and it’s just taken us best part of a century to understand this. If so, then this is not simply a matter of getting fiscal and structural policies right. It raises serious questions about the ordering of society. After all, a large number of people depend on there being significantly positive real returns on essentially risk-free assets. If significantly positive real returns on risk-free assets are a thing of the past, we owe it to those people to stop pretending we can restore their lost returns through “confidence-boosting fiscal adjustment” and “growth-friendly structural reforms”. They simply aren’t going to be able to live comfortably in their old age on the interest on risk-free savings.

The truth is we do not know when, or if, positive real returns on risk-free assets will return. If the future path for growth in future is low to zero, then they may never return. If this is the case, then the solution to the “Great Divergence” must be for nominal risk-free rates to drop. Permanently.

Related reading:

Weird is normal – Pieria

No, you can’t have your risk-free returns back – Tomas Hirst, FT Alphaville

“The fact is that a significant proportion of the human race now expect to receive returns on financial assets that are far removed from the real ability of the economy to generate them. I don’t know why this is, but in my view we should be looking at things like labour market dynamics, longevity and pension expectations.”

Considering the trend to leave workers out on their own with no pensions I think sounds great to the market class but this post recognizes that those pensions are indeed what the rich are currently using to finance themselves so when the pensions are gone who will fund them?

Maybe a principal structural element of the failing Zeitgiest is the recognition by The Rich that they are personally, for their lifetimes, totally immune to what happens to the rest of the planet. Whether in terms of die-off of “lower species,” including the “workers” and “useless eaters,” or phytoplankton, and monkeys, and all but ornamental trees placed just so to satisfy their personal aesthetic of the moment. All accounted for in terms of “money” or debt or whatever it is, that they and the people they have insinuated into all the nodes of power now “manage” and protect from any iota of comity and responsibility. Personal impunity and immunity means never having to say you’re sorry, or do jack sh_t about the messes your indulgences make, Daisy Buchanan. And IBG-YBG is all one needs to know about political economy. ‘Cuz after all, “Après moi le déluge”, and Its Classical Antecedents — http://tradicionclasica.blogspot.com/2006/01/expression-aprs-moi-le-dluge-and-its.html

The problem the rest of us have, us ordinary shlubs who create the REAL wealth (and yes, the “excess population” and consumption, thanks to “marketing”) that the whole idiocy spins and leverages around, and who make possible and (for a buck or two) construct and service the “Elysiums” and those Beautiful Balloons with their “luxurious open layouts” and Infinity Pools and other Hanging Garden frippery that are attached to the Native Soil only by the one-way conveyors of Pleasure Principle condiments and all that wonderful Funny-Munny Wealth, is that the Really Rich really, as Scott Fitzgerald observed, are very different from the rest of us. A little assortment of observations and reasons why:

The Rise of the New Global Elite — F. Scott Fitzgerald was right when he declared the rich different from you and me. But today’s super-rich are also different from yesterday’s: more hardworking and meritocratic [to which I say that is generally pure bullsh_t — Kim Dotcomm, Saudi princelings, Imperial General Officers, Banksters?], but less connected to the nations that granted them opportunity—and the countrymen they are leaving ever further behind. What’s that they say in Maine? Ay-up. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/01/the-rise-of-the-new-global-elite/308343/

The Rich Are Different From You and Me: They Don’t Care About Jobs and Their Money Buys Politicians

The rich don’t just have more money than you and me. The rich use their money to legally bribe politicians to support policies that favor themselves over the middle class in the auction that we call elections. And the policies they support are different from those supported by the majority of middle class Americans voters.

“We are the 99%” isn’t just a brilliant piece of political messaging. It’s an accurate reflection of the division of wealth and power between the richest 1% and the other 99% and the degradation of American democracy into a political auction in which politicians are bought by the highest bidder. Until we change this — if necessary by a 28th Amendment to the Constitution declaring the corporations aren’t people and money isn’t speech — American democracy will continue its descent into a hollow shell in which political power is wielded not by the people but by a tiny oligarchy of the richest Americans and their political servants.

A critical new study by The Russell Sage Foundation shows the extreme disconnect between the opinions of most Americans and those of the top 1%. The results of that study, as well as another study by the Sunlight Foundation, shows that campaign contributions are even more concentrated in the richest 1% than wealth is. Is it any surprise, then, that the policies of our government more closely reflect the interests of the wealthiest Americans who contribute the bulk of campaign financing, than they do the interests of the other 99%?

According to a recent CBS News/New York Times poll 57% of Americans believe that the economy and jobs are the country’s most important problem and only 5% believe the most important problem is the budget deficit/national debt.

The wealthiest Americans see it differently, According to The Russell Sage Foundation survey of the wealthiest Americans (with an average net worth of $14 million) 32% think the country’s most important problem is budget deficits and only 11% think it’s unemployment. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/miles-mogulescu/the-rich-are-different-fr_b_1154270.html

And the differences go deep, as explored in this little article:

Wealth, poverty and compassion

The rich are different from you and me

LIFE at the bottom is nasty, brutish and short. For this reason, heartless folk might assume that people in the lower social classes will be more self-interested and less inclined to consider the welfare of others than upper-class individuals, who can afford a certain noblesse oblige. A recent study, however, challenges this idea. Experiments by Paul Piff and his colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, reported this week in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, suggest precisely the opposite. It is the poor, not the rich, who are inclined to charity….

In this case priming made no difference to the lower classes. They always showed compassion to the latecomer. The upper classes, though, could be influenced. Those shown a compassion-inducing video behaved in a more sympathetic way than those shown emotionally neutral footage. That suggests the rich are capable of compassion, if somebody reminds them, but do not show it spontaneously.

One interpretation of all this might be that selfish people find it easier to become rich. Some of the experiments Dr Piff conducted, however, sorted people by the income of the family in which the participant grew up. This revealed that whether high status was inherited or earned made no difference—so the idea that it is the self-made who are especially selfish does not work. Dr Piff himself suggests that the increased compassion which seems to exist among the poor increases generosity and helpfulness, and promotes a level of trust and co-operation that can prove essential for survival during hard times. http://www.economist.com/node/16690659 Though of course the neolibs and their Betters are working hard to sucker us mopes into savaging one another, to clamber up and stand on the other bloke’s shoulders as the oceans rise, seeking that last gasp of air…

Hey JT

It’s late & I can’t sleep so I suppose this won’t be read by anyone…

I usually find your comments dense (as in densely packed) & difficult to comprehend but this one is a beauty – no sarc. intended.

I actually “got” all the references.

I’m ignorant. I need some definitions.

What are:

a “Nominal Rate”

b “Real Rate”

c “risk-free assets”

Resources or wealth?

If wealth we know this. When “resources” are used I tend to think of raw materials, and this cannot the definition.

Nominal rate=stated rate of interest on an instrument

Real rate=actual return after inflation

Risk free assets=US treasuries

I’m also confused, as I can’t see how the situation benefits the investor class. They invest at a stated rate but receive lower returns.

I have to admit to a little confusion here myself. In normal econo-speak (and investor-speak too, so far as I can tell) “nominal” refers to the unadjusted number. Say you buy a bond that pays 5%–5% is the nominal rate. The “real” rate is simply the nominal rate adjusted for inflation/deflation. So if your bond pays 5% a year, but there’s 3% inflation per year, your real rate would only be 2%. The real rate accounts for the reduction of purchasing power due to inflation, has always been my understanding. It’s econ 101.

But then what can it mean that real rates are below nominal rates in the absence of inflation?

So where is that 2% disappearing to? What is causing the nominal yield to be diminished, if not inflation? Is it the financial managers siphoning off large chunks of the return before passing it on to ordinary investors? Is that what Frances is saying here:

One of you finance pros help us out here.

This is one of the many mysteries on this chart. I think what it tells us is that consols are priced on the basis of inflation expectations which are currently running some way above reality. The fact that the gap is 2% suggests that people still believe central banks will meet their targets.

Thanks for the reply.

Next question: how is “ex ante real consol yield” calculated, exactly? What variables go into that calculation? Or is something like TIPS used as a proxy?

I’m hoping you get an answer on that. Without knowing how that number is calculated, it’s meaningless.

That raises the interesting question of who determines reality?

Nominal Yield = Real Yield + Inflation Rate

That’s just a basic identity of interest rates. It is true by definition. The real yield is calculated by taking the nominal yield and subtracting the rate of inflation.

So the only way to have a ‘gap’ over an extended period of time that is not explained by inflation is either 1) inaccurate data collection, or 2) playing games with definitions.

Which is a different way of asking how much of the management failure in the Western world is negligence and how much is theft.

What is the inflation rate?

http://www.cnbc.com/2015/05/22/medical-cost-inflation-highest-level-in-8-years.html

AND

https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2014/12/03/historically-slow-growth-health-spending-continued-2013-and-data-show-underlying-slo

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpid1412.pdf

The index for prescription drugs rose 0.9 percent, and the hospital services index increased 0.5 percent (page 2)

Who is telling the truth???? Of course, maybe outrageously rising drug costs slow health spending.

And you know what? I have never defaulted, and never been late in making a payment…but somehow, I can’t come close to getting such low interest rates…hmmmm…

The use of aggregates is one of the those things that drive me insane. Its like saying that year in and year out, there is between 4 and 2% growth (really, it is very rare that there is actually negative growth). That is true, and it is absolutely ear elephant to the fact that the 0.1% get richer and richer, and wage earners get less and less, and everybody else is stagnant at best.

Now, maybe some people reading this think that their health care costs are declining and quality is going up as well!

I think the recent economic troubles (those 500 year anomalies that happen every 10 years) prove that economists don’t actually understand how finance works – or it they do, they are not going to share it. I think the truth of the matter is that the rich are getting much richer and everybody else isn’t. If you have the finance system set up so that if your super wealthy, and your too big to fail – well, let people piddle away their time yammering about the FED and real interest rates, nominal interest rates, and what the FED is going to do with regards to interest rates – instead of talking about how the FED (i.e. the Banks, but I repeat myself) decided that the MOST important thing was to make sure that no rich person suffered any significant loss.

Inflation is Chinese coffee pots. Unless they get better and connect to the internet and spy on your morning activities. In that case, we have hedonics adjustments to adjust the price back down to where it should be sans technological advancements. But that doesn’t change the price at the store, of course.

Also, think financial resources, not natural resources.

Lets take an example.

You’re a parents with one kid. Yous save some of yous incomes to pay for the kid’s college education someday. You invest in 10 year treasury bonds that yield 2.2%. This is nominal yield. The future is hard to predict, but you are betting on the Fed to make inflation average out at 2% per year. That means your “real yield” is .2% (point 2%) This means that not only have you preserved your purchasing power for college tuition, but you are coming out 2 tenths of a percent ahead! Compounded every year!! This is making capitalism work for you. It’s also better than doing nothing and taking out an 8% student loan at the last minute.

This concept works even better if you become a carry trader and can borrow at near ZIRP rates and use between 10X and 100X leverage. Then all those two tenths can add up to real money!!

It’s also assuming that you can actually save some of your income. More often than not the people who were taking out student loans were people who were sold the idea that going to school, even if they couldn’t afford it, would yield a return on their “investment” and improve their economic situation.

Yes, it’s definitely better that if you can save for future expenses that you do so. However, it’s not exactly a realistic for the kid of a Walmart worker to expect that the same mom and dad that are being told to save for retirement also save for their college with their $400 a week job. It’s even more depressing when you consider the investment class are the same people insisting that labor costs be cut and each worker be told they are on their own and expendable. But hey, viva la capitalism and selling out your fellow man is totally worth a 2 tenths of a percent annually(as long as they don’t get to downsizing YOUR job in their neverending quest to cut labor and give investors a return.)

How does it work if you are a minimum wage worker’s kid? Can you just skip rent so that you can save for school for your kid using these bonds?

I guess capitalism is only supposed to work for some of the people some of the time and the moral of the story AGAIN is to pick your parents carefully.

I wanted to stay a little upbeat. The 60s-70s middle class had two kids and a stay at home mom.

So I already upped it to a dual income family and killed off one of the kids.

And chasing a 8% annual inflation tuition by saving what’s left of the $55k ave household income and “investing” it in two tenths % return Treasuries don’t get you there either. Besides health care is competing, quite well, for your income dollars.

Then there is housing. Higher is “better” there too. If you owned one long enough, home equity loan.

So, obviously, you can’t buy anything else – which is why we have “deflation”, or really “disinflation”.

Poor people needn’t worry about any of this at all, of course. Well, you can enlist in the army for 4 years (girls too) and get a partial scholarship when you get out. I knew one guy that did that and the half of the tuition he had to come up with was more than his gross army pay for 4 years.

The value or return on investment of interest income is deminished not only by inflation but also by the income tax in a special way. wp.me/p42WQA-1E

The long term capital gains tax was created in 1921. The divergence begain in 1921 resulting in higher nominal interest rates.

Agreed. That’s one of the reasons it seems obvious to me that we need to know how the real yield is calculated to make any conclusions about this divergence. The difference between pre-tax and after-tax income can be material, especially with niche products.

“The truth is we do not know when, or if, positive real returns on risk-free assets will return.”

Why should they? Risk-free assets should pay no than 0% nominal else someone is receiving welfare and not welfare according to need but welfare according to the amount of those assets they own.

This is simply incredible. It’s almost as if someone came up with a scam to somehow skim the difference!

There is a common metonomy in using “resources” as a synonym for money that prevents people from seeing how profound our misallocation of actual resources is. The author worries about un-funded pensions even as there is massive and deliberate, systemic unemployment. He worries about people paying for their retirements even as our industrial system scorches the atmosphere, reducing forests to ash as the arctic melts.

This essay is well intentioned, trying to point out to participants of the financial economy the degree to which their system is corrupted, but he’s puzzled because he thinks its about the market miss pricing risk when in fact it is about rentiers having captured the system and re-tooled to their benefit.

But his is the perspective of money, not resources and so he can’t see the obvious causality of capture: the only things our so called conservatives conserve is money.

The answer will depend upon what one believes the function of an interest rate is. The classical and neo-classical description tells us the interest rate functions to induce investment. Keynes’ theory of uncertainty tells us the interest rate is to persuade investors to part with their money. While the two narratives may appear of little difference the psychological motivations underlying each are profound.

Under the former the above chart suggests investor expectations are for a greater return on investment than in the past; under the latter investors are much more cautious and demand a higher return before they will take the risk.

Or, the third option that those with the power to affect the rate will do all within their power to preserve the innumerable un-realistic claims on future income embedded in current prices, even with all their massive distortions. As this process is conserved, now for at least the last 8 years, the liquidation of real productive actual resources advances.

I think maybe it was Twain who said “markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent” but at this particular juncture the efforts to sustain the appearance that we actually have a “market” in finance is actively liquidationist.

It isn’t a market if the major players in it can’t go bust. Period. The re-allocation of real resources from poor to rich is a feature, not a bug, of a system carefully decorated to look like a market while shedding all risks onto those who don’t have access to it.

John Maynard Keynes had that line, actually.

Will Rogers had a famous line about markets; return of his principal concerned him more than return on his principal.

Kissinger once said, “war is the health of the state.” But major powers can’t go to war with each other anymore (at least not without blowing the whole world up).

If we didn’t have nukes, we’d have fixed this all with a command economy a long time ago. No war means the only other solution is mass labor action. I keep thinking that, eventually, the auto workers HAVE to go on strike, given how the UAW keeps fucking them around.

But no general strike, no change. Why should the capitalists, er, rentiers, give a shit how bad the economy gets as long as they’re still raking it in? They never cared about the people killed in wars, since they weren’t among the dead.

Kissinger may well have said that, but the phrase was coined by Randolph Bourne in 1918.

Dammit.

Thank you.

I think inflation rate fakery must have something to do with this. But the precise mechanism eludes me. For example, the official rate of inflation here in the UK is zero. For me, as a quasi rentier with assets and no borrowing, don’t run a car, enough spare capital to divert to my own energy generation and don’t travel unless I want to, I’m probably in the group for whom the official rate of inflation is supposed to apply to. Therefore, my yield curves match the “official” data.

The young chap next door with the massive student loans and about to move into some of the most hideously expensive rental accommodation on the planet, or the chap in the other next door earning near to minimum wage and spending it on auto loan repayments, iPhone running costs, sky-high insurance, pension plan pickpocketing and eating out, well, their inflation rates are pretty stratospheric.

There’s an obvious inconsistency between the first and second charts for the year 1800. If inflation briefly soared to 36%, then the ex ante real yield on consols was not 6% as shown by the orange line in the first chart, but rather minus 30%.

Likely the discrepancy derives from data of different frequency, or from smoothing. No matter. The big picture is that nominal and real yields were tightly anchored for centuries, both in Britain and elsewhere.

Even when Britain suspended the gold standard, as it did during WW I, everyone understood that the gold link would be restored when the exchequer’s finances permitted (as indeed it was in 1925). Rentiers didn’t react to temporary episodes of inflation, when experience showed that it would be reversed in due course.

In the U.S., the 12-month change in CPI reached 20.4% in June 1917, while 10-year T-notes yielded 3.81% (GFD data). Bond yields simply did not respond to temporary surges in inflation. By 1921, U.S. commodity prices were cut in half from their inflated wartime levels, restoring rentiers’ purchasing power.

So why did inflation become entrenched after WW II? Two reasons. First, Bretton Woods made the U.S. dollar the global reserve asset. Second, by 1945 as the war ended, U.S. government securities (a minor portion of the Fed’s prewar assets) became more than half of the U.S. monetary base, and just carried on rising. Chart:

http://tinyurl.com/o4kl4u2

When paper claims are substituted for a metallic standard, trust evaporates. Unlike government paper, gold cannot be printed by unscrupulous government-licensed banksters.

Gold doesn’t control inflation by engendering trust but by inflicting depressions and eventual deflation. The inflation buffer under such a monetary regime is misery.

Crippling depressions break the ability of businesses to raise prices and workers to raise wages; since the Great Depression there is no appetite for enduring such conditions again.

Depressions were largely a function of preceding wartime inflations while the gold standard was suspended.

Had Britain relinked to a gold in 1925 at a devalued exchange rate instead of at the prewar parity, it would not have been obliged to ‘sweat out’ the prior inflation.

The single-minded rigidity with which the gold standard was enforced (ultimately leading to its demise) reflected deep distrust of currency manipulation, which was once regarded as a capital crime.

Like your goodself, I am thankful to now live in a Paper Paradise. Is it true that J-Yel keeps a gilt-framed photo of John Law on her credenza?

So you think fiat is unbacked? Try not paying your taxes with it and you’ll learn quickly how sternly backed fiat is. Indeed, it is not gold that would back fiat but the taxation authority and power of government that would back gold.

So let’s quit yearning for a previous form of unethical fiat creation, eh? You’re smarter than that, I hope.

IRS:

Governments that have confidence in stable money don’t need inflation adjustments.

If the government-subsidized banks create 97% of the money supply then why aren’t they responsible for 97% of the price inflation too?

Stable money, based on the mining rate of a shiny metal? Do you wish to limit real economic growth to such an arbitrary rate? Are we too stupid and wicked to not find a better, ETHICAL solution?

Central planning, particularly when implemented by a bank cartel, poses insoluble ethical problems.

Yes, government privileges for the banks have to go and that will require the abolition of much private debt in a manner that does not disadvantage non-debtors, both for the sake of justice and for political expediency. See Steve Keen’s “A Modern Jubilee” for a rough outline of how that might be done or similarly.

“Central planning, particularly when implemented by a bank cartel, poses insoluble ethical problems.”

See your happy ideological representative of the MPS posse Jim, numbers, charts and emotive beliefs about stuff is a poor substitute for history as one proceeds the other…

Liberation Theologies, Postmodernity and the Americas

By David Batstone, Eduardo Mendieta, Lois Ann Lorentzen, Dwight N. Hopkins

“In 1985 david stockman. who came from a fundamentalist back-ground, resigned from his position as chief of budget for Regan’s government and he published a book entitled “the Triumph of Politics. He reproached Reagan for having been a traitor to the clean model of neoliberalism and for having favored populism. Stockmans.s book develops a neoliberally positioned academic theology, that does not denounce utopias, but presents neoliberalism as the only efficient and realistic means to realized them. It attacks the socialist “utopias” in order to reclaim them in favor of the attempted neoliberal realism. according to Stockman, it is not the utopia that threatens, but the fulse utopia against which he contrasts his “realist utopia of neoliberalism. Michel Camdessus, secretary General of the IMF, echoes the transformed theology of the empire grounding it in certain key theses of liberation theology. In a conference on March 27, 1992 he directed the National Congress of French Christian Impresarios in Lille Mid discussion he summaries his central theological theses:

Surley the Kingdom is a place: these new Heavens and this new earth of which we are called to enter one day, a sublime promise; but the Kingdom is in some way geographical, the Reign is History, a history in which we are the actors, one which is in process and that is close to us since Jesus came into human history. The Reign is waht happens when God is King and we recognize Him as such, and we make possible the extension, spreading of this reign, like a spot of oil, impregnating, renewing and unifiying human realitys. Let Thy Kingdom come….” – read on

Page – 38, 39, 40

Skippy…. you and beardo actually suffer the same cog dis, you just have a slight variation wrt mental red shift e.g. the central planing starts before central banks…. eh…

Please inform us how a return to Glass-Steagall with government subsidized banks solves the problem of unequal protection under the law? Did not Watts and other redlined urban centers burn BEFORE Glass-Steagall was repealed?

Government-subsidized banks are far more than a mere payment system or have you not yet comprehended that “loans create deposits”, skippy?

WTF does your comment have to do with the above – ???? – and where did your diatribe about Glass-Steagall pop out from – ???? – a chariot at the bottom of the red sea – ????

What kinda special cognitive defect does one suffer when they respond to historical accuracy with completely detached Pavlovian foaming.

The aforementioned was to illustrate the “Central Planing” is several moves preceding central banks and from a “fundamentalist perspective” detached from academic rigor or did you not understand the religious overtones in the guise of economic thunkit.

Loans and deposits and payment system…. groan~

Review corner….

” Basically because debt and deficit are too hard to grasp.

What’s hard to grasp is the simplicity of the basic operations, initially, against a backdrop of the basic functions of the institutions, and the meaning of terminology like ASSETS vs LIABILITIES, which I had reverse in my mind for banks. (I had assumed that my bank acct was my bank’s “asset” — wrong.)

A “budget deficit” would be a shortfall for a business, but NOT for a currency issuer. It just means that LESS TAX was subtracted from currency users as MORE SPENDING was added to the accounts of currency users.

The operations are basic grade school arithmetic, but on spreadsheets on computers with big numbers and much of spending automated. (I use automated spending on my own checking acct, to pay utility bills.)

Currency users are everyone outside of the Govt, aka private sector.

A DEBT would seem to be funds borrowed for households or business operations, but NOT for a currency issuer. This DEBT is merely a bunch of savings instruments that are highly wanted by various persons and institutions with plenty of profits and savings.

For a currency issuer, it would be impossible to collect taxes in that currency, unless the currency had already been issued (spent) in the past. It would be impossible to tax or borrow Martian Republic currency because the Martians have never deficit spent any.

It would be impossible to tax or borrow in USA currency if the USA have never deficit spent previously. THEREFORE, logically, US spending cannot “come from” borrowing or taxing. USA provides the currency by which it MAY collect taxes in the future, after the fact of spending.

(Why it needs tax collection at all is a longer counter intuitive discussion)

The Debt is a poor word choice for LIABILITIES. Once I learned that if anyone has a bank balance of financial ASSETS, those are by definition the LIABILITIES of the banking institution that provides the accounts, and therefore the bank OWES their customers a balance statement, and customers spend their bank IOUs. Then transferring that logic to the Govt means that Govt Debt is very similar, accounts that hold private party savings, the amount that is OWED to the customers who own the deposits.

the Govts LIABILITIES = the Non-Govt’s ASSETS.

Assuming that as humans in business we WANT more financial assets, for all of us collectively, then we therefore WANT more govt’s liabilities. What do they call that? Oh yeah, an ACCOUNTING IDENTITY.”

Sectoral balances, people think it’s a theory. It’s not. If you reject sectoral balances, you reject math.

Skippy…. at the end of the day its a quality not quantity drama, so, the next question is how did that state of affairs manifest…. ummmm… religious nutters – ????

Re “Review corner”: Who are you quoting? And it’s a bit disingenuous to imply I don’t understand MMT when I clearly do. Talk about dredging the Red Sea, will you?

But as for bank liabilities, my point is that the liabilities of the banking cartel AS A WHOLE are largely virtual since physical cash and the mattress are a very poor substitute for a risk-free, modern fiat storage and transactions service – which service monetary sovereigns should provide for all of their citizens and fiat users instead of guaranteeing the deposits of what should be 100% private banks with 100% voluntary depositors.

But please let’s hear YOUR proposals for reform? In the past you have deferred to Yves’ in that regard. Well, Yves advocates “utility banking”* and a return of Glass-Steagall so that is what I assume you still support.

*as if regulating what is essentially a counterfeiting cartel is akin to regulating water and power companies!!!

Because, in reality, 90% of the money supply is created by private banks, as debt. That’s where all the little asset-price inflation bubbles that have been rising and popping all around have been coming from, while core inflation isn’t budging. The real money supply is horrifically insufficient. I have a hunch that that vast private debt overhang likely explains this better.

Let’s not forget that houses are considered assets and that many have been priced out of that market and are either homeless, living in crummy apartments or overpriced rental houses or living with their parents.

Let’s also not forget that wages (including benefits) have been deflated in real terms with automation and outsourcing financed by the banking cartel.

So the banking cartel has squeezed the poor via price inflation AND wage deflation.

But yes there is too little real money in the system or it’s in the hands of the banks as so-called “excess reserves.” More real money should be distributed to the population while it is clawed back from the banks to compensate.

I think paper money is cool if you have some, and other people will give you stuff for it.

But as far as gold goes, civilization has NOT been using gold coins for many centuries now. We have had a long period of bi-metal backed currency combined with fractional banking in the domestic economy. We still had booms and busts. (say, the late 1800s Financial Panics)

In pre -Nixon times international trade surpluses/deficits were settled in gold, even tho we had fully gone paper money domestically and had a Fed who could backup banks with the printing press. Today, the defining characteristics of this century seems to be bigger booms and busts.

So, I’d say fractional banking gone awry and trade deficits* are the persistent cause of economic troubles. We did kill the barbaric relic, didn’t we?

* Tho you can mask the disease easier with a reserve currency.

Disclaimer: At this point, I do not want to pay off the national debt in gold!

A bimetallic standard is more volatile than the gold standard. It also introduces the same ‘dual mandate’ problem we have now (monetary stability and maximum employment).

Nevertheless, even bimetallism put a brake on the absurd arbitrariness of today, in which one PhD Econ advocates a ‘malign dovish hold’ while another one pleads for a ‘one-and-done hawkish hike.’

*rolls eyes, lights another spliff and blows a smoke ring*

I was using the term “bimetallism” merely to try and cover more centuries because I couldn’t remember exact timeframes off the top of my head when we were gold only fractional banking, vs also silver certificates and whatever fractional banking.

The U.S. experienced five depression prior to the Great Depression. You can’t lay responsibility for them on events which occurred afterward.

Also, please explain how a moderate spike in inflation in 1920 resulted in the most severe economic slump on record nine years later.

I don’t support a government-enforced gold standard, but I don’t think your usage of the great depression is accurate, either.

The primary cause of most “crippling depressions” in the industrialized world is the unsustainable inequality that precedes them. It’s the distribution of financial resources that matters, not whether the purchasing power of the currency increases or decreases a few percentage points each year. Plus, one of the major factors of the human suffering in the particular American experience of the 1930s was the Dust Bowl, a development in the physical world, not the financial one.

There’s a continuity between physical and financialfraud worlds noted by many who post here. Lots of positive-feedbacks. Re the US Dustbowl, greed and a “mechanical plowing bubble” had a large part if you looks for explanations and history outside the Koch-approved texts:

The seeds of the Dust Bowl may have been sowed during the early 1920s. A post-World War I recession led farmers to try new mechanized farming techniques as a way to increase profits. Many bought plows and other farming equipment, and between 1925 and 1930 more than 5 million acres of previously unfarmed land was plowed [source: CSA]. With the help of mechanized farming, farmers produced record crops during the 1931 season. However, overproduction of wheat coupled with the Great Depression led to severely reduced market prices. The wheat market was flooded, and people were too poor to buy. Farmers were unable to earn back their production costs and expanded their fields in an effort to turn a profit — they covered the prairie with wheat in place of the natural drought-resistant grasses and left any unused fields bare.

But plow-based farming in this region cultivated an unexpected yield: the loss of fertile topsoil that literally blew away in the winds, leaving the land vulnerable to drought and inhospitable for growing crops. In a brutal twist of fate, the rains stopped. By 1932, 14 dust storms, known as black blizzards were reported, and in just one year, the number increased to nearly 40. http://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/green-science/dust-bowl-cause.htm

I read that even the Aborigines and those famous no-footprint Bushmen of the Kalahari are struggling to survive, even with their vaunted survival skills, in the face of “Western Culture…”

“Howya gonna keep ’em down on the farm,

After they’ve seen Par-eeee?”

Yep. That is inequality in action. The farmers that ran into trouble were precisely the ones caught in the financial speculation death trap of groaf-based debt (AKA the Roaring 20s). The profits were privatized by those higher up in finance and industry, while the losses were externalized onto society.

It’s almost like bank created debt to fund fossil-fuel based machines to push industrial agriculture to enormous scale is somehow not a good use of resources…

“by … government-licensed banksters.” Jim Haygood

Therein lies the problem, not the absence of expensive fiat.

The inflation rate chart presumably shows year on year inflation….

But consols are perpetual, so the difference between ex ante real and nominal consol rates should show inflation expectations in perpetuity (though weighted/discounted as for consols), and thus minimally related to YoY inflation. This is actually borne out by the charts – there is high inflation volatility, but basically no price rise at all till 1915. After which, inflation is positive on average and this is reflected in the real/nominal yield divergence.

As to the difference being two percent today even though current inflation is zero… Well I guess the market expects the BoE to hit its inflation target in the long run, even though it’s somewhat failed over the last few years.. I guess we’ll find out whether that’s an optimistic hope or not..

Very good point. But it brings up the issue raised by Robert Shiller in his book Volatility — that both stock and bond prices are way too sensitive to current conditions, even though one bad year has little effect on the long-term prospects for corporate earnings and inflation.

Bond markets — formerly insensitive to wars and depressions — changed after WW II. So did the monetary standard. Coincidence? Twenty-four hours in a day, twenty-four cans in a case of beer — I reckon not!

“that both stock and bond prices are way too sensitive to current conditions,” Jim Haygood

Of course. That is inherent in a money supply that is lent, rather than spent, into existence and in frantic government/central bank interventions to compensate for the inevitable busts.

Pure counterfeiting, in moderation, would be far superior to our current system since then we might have inflation-free growth without the bust.

Indo-European languages once used base-12 numbers; hence “dozen” and “gross” – or twenty-four cans in a case, or hours in a day.

Base ten came in later, not sure where from.

I guess I’m saying it’s just a coincidence.

Hi Amir,

The price level rose more or less continuously from 1750 to 1816. During this time there were persistent gold shortages which culminated in the suspension of gold convertibility in 1797. The price level fell after restoration of the gold standard in 1816 and fiscal austerity in the 1820s, but never really regained its pre-war level let alone the 1750 level. However, it did remain pretty stable for the rest of the 19th century.

The pricing of consols in the past reflected their perpetual nature. The volatile inflation of the time made little difference to their long-term yields. I included the price level chart because Keynes observed that interest rates were correlated with price level rather than inflation, but I don’t think this is entirely true. Real and nominal yields rose during the Napoleonic wars as the price level rose, but afterwards fell back to pre-war levels even though the price level did not return to its pre-war level. Seems that the elevated price level was regarded as temporary, even though it turned out not to be.

So the question is, why did we apparently stop pricing consols as perpetuals? Or, alternatively, why did we start expecting changes in the price level to be permanent, rather than temporary as they always had been in the past?

Since I think it’s always good to look outside the little world of finance to the real world, I’d ask:

Does the divergence, especially lately, reflect the collision of the economy with real-world constraints? That is, resource constraints. Granted, we don’t think o fthat as going back to the 30s. I can’t propose a mechanism, but it’s the sort of anomaly I’d expect from hitting the wall.

Looks to me like things went off the rail right about when the Beatles became superstars.

After that it was the Animals, Led Zepplin, Pink Floyd, The Who and then punk rockers like the Sex Pistols and Ozzie Osborne.

Wouldn’t you want a little extra to lend money to a country that produced a freak show like that? It’s not exactly the same place that patrolled the seas with dudes like Admiral Nelson behind the tiller and poets who wrote in rhyming couplets. Oh man. Think about that. Lending money to drug fiends and artists is never a good idea. Even if you do have MMT.

Now things look like they’re settling down. It may be the Adele inflluence, since she’s kind of “classic British”. She even writes lyrics that rhyme. Some of them anyway.

Should anyone ever expect substantial returns on something that is risk free?! The most I would ever hope for is for it to match inflation.