By Nomi Prins, a former Wall Street executive, the author of six books, a speaker, and a distinguished senior fellow at the non-partisan public policy institute Demos. Her most recent book, All the Presidents’ Bankers: The Hidden Alliances that Drive American Power (Nation Books) has just been released in paperback and this piece is adapted and updated from it. Originally published at her website

On August 27th, I had the opportunity to address the Aspen Institute, UNIFIMEX and PWC in Mexico City during a Q&A with Patricia Armendariz. Subsequenty, on August 28th, I gave the opening talk at the annual IMEF conference. The main issues of concern to local Mexican banks, as well as to Mexico’s central bank, are:

1) How the Federal Reserve’s (and to a lesser extent ECB’s and People’s Bank of China) policies and actions have, and wlil continue to impact their currency and interest rate levels, and

2) The risks posed by the structural, and ongoing problems of too-big-to-fail banks, which remain as much a US as a Mexican problem as manifested by heightened economic, market and financial stress.

I posted the slides from my talk here, including the ten main risks that Mexico (and really all countries) are facing today, as well as the four factors of volatility that I have spoke about many times before. Much uncertainly emanates from central bank policy and the associated artificial stimulation of mega banking institutions and capital markets throughout the world. There is no foreseeable remedy to the long-term damage already caused, and that will continue to grow in the future.

What follows is a related piece that I co-authored with researcher, Craig Wilson that first appeared in Peak Prosperity:

Too big to fail is a seven-year phenomenon created by the most powerful central banks to bolster the largest, most politically connected US and European banks. More than that, it’s a global concern predicated on that handful of private banks controlling too much market share and elite central banks infusing them with boatloads of cheap capital and other aid. Synthetic bank and market subsidization disguised as ‘monetary policy’ has spawned artificial asset and debt bubbles – everywhere. The most rapacious speculative capital and associated risk flows from these power-players to the least protected, or least regulated, locales.

The World Bank and IMF award brownie points to the nations offering the most ‘financial liberalization’ or open market, privatization and foreign acquisition opportunities. Yet, protections against the inevitable capital outflows that follow are woefully inadequate, particularly for emerging markets.

The financial world has been focused largely on the volatility of countries like China and Greece recently. But Mexico, the third largest US trading partner (after Canada and China), has tremendous exposure to big foreign banks, and the largest concentration of foreign bank ownership of any country in the world (mostly thanks to NAFTA stipulations.)

In addition, the latitude Mexico has provided to the operations of these foreign financial firms means the nation is more exposed to the fallout of another acute financial crisis (not that we’ve escaped the last one).

There is no such thing as isolated “Big Bank” problems. Rather, complex products, risky practices, leverage and co-dependent transactions have contagion ramifications, particularly in emerging markets whose histories are already lined with disproportionate shares of debt, interest rate and currency related travails.

Mexico has benefited to an extent from its proximity to the temporary facade of US financial health buoyed by Fed policy, but as such, it faces grave dangers should any artificial bubble pop, or should the value of the US dollar or US interest rates rise.

There are other clouds forming on Mexico’s horizon. In the past month, the Mexican stock market has fallen 6 percent. Its highs were last seen in September, 2014. Shares in the nation’s largest builder, Empresas ICA SAB, just fell to a 12-year low as lower growth expectations.

(Source)

Because of currency misalignments based on central bank machinations, the Mexican Peso sits near all time lows vs. the US dollar. The Central Bank of Mexico just announced a currency boosting round of $8.6 billion of Pesos over the next two months, with likely more to come. This impinges upon its reserves.(Source)

Mid-level Mexican financial firms will struggle with access to credit should the air in the tires of this global liquidity boosting exercise continue to leak out. Other problems loom on Mexico’s horizon based on a host of interrelated factors.

These include the potential of capital flight, liquidity loss, over-reliance on external debt and investors, oil price declines (oil revenues account for about one-third of Mexico’s federal government budget), economic downturn in the US or Mexico, and rising volatility due to central bank policy shifts impacting interest rates and currency relationships, geo-politics, credit defaults, or additional big bank crimes.

The high concentration of large banks in Mexico and in the US presents extra systemic risk. Local Mexican firms and individuals, as well as foreign investors should consider these co-mingled factors and hedge against them for protection.

Capital Flight Due to US Rate Hikes, Real or Anticipated

The possibility of US rate hikes, or even the threat of them, could freeze demand for non-US stocks and bonds – everywhere. If we learned anything from the US financial crisis, economic hardship in Greece and other Southern European countries, and the rout in the Chinese stock market, it’s that capital flight, particularly leveraged capital flight, can crucify an economy, especially high debt burdens accentuate the process.

Mexico, though somewhat protected from financial upheaval during the first leg of the 2008 financial crisis, may be the next victim of capital’s mercurial tendencies for that very reason. Mexico’s relative stability and liberalized financial markets have invited more foreign capital through these channels, which means more can leave to return to headquarter countries, or seek opportunities elsewhere, in emergencies.

In addition, heightened “de-risking” (or the reducing of counter-party agreements and cross-border remittances between the US and Mexico) will impact future remittance flows. Though de-risking practices are officially designated to thwart money launderers and drug-dealers – the true effect of the closing of bank branches or reduction of services that enable remittance flows burdens the population and the local banks that rely on them.

Big Bank Concentration and Counterparty Risk

Mexico’s domestic bank concentration problems have marginally improved since the financial crisis, but not by much. As of 2014, just five of Mexico’s private sector banks hold 72 percent of all financial assets. The top two, Banamex, a unit of Citigroup Inc., and BBVA Bancomer, a unit of Spain’s Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA, hold 38 percent of all assets. (Source) (Source)

Concentration has accelerated in the US. Since the financial crisis, the Big Six US banks (JPM Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Wells Fargo and Morgan Stanley) have grown in terms of assets, deposits, cash, trading assets and derivatives volume.

In terms of counter-party risk, from a credit and derivative perspective, the fewer banks operating in any sphere, the greater the risk that a collapse in any one of them triggers a domino effect in the others. The main foreign banks in Mexico, and those engaging in business with Mexican banks, can quickly close services and shift capital and credit from the country, or place barriers to retrieve it, in a pinch.

Ongoing US Bank Bailouts and Mexican Fallout

The US Federal Reserve buying program, though officially over, has rendered the Fed the largest hedge fund in the world, with a $4.5 trillion book of securities, more than a dozen times the figure of seven years earlier. The mortgage backed securities component remains at about $1.5 trillion, up from zero seven years ago.

Mexico was fortunate not to have been on the US bank radar screen to receive, or be induced to borrow against, the $14 trillions of dollars of toxic US-bank made assets. US bankers mostly focused on selling these subprime assets into Europe. Thus, Mexico escaped the fallout that countries like Greece and Spain felt.

Still, Mexico’s financial conditions are showing increasing signs of weakness, despite comparatively low inflation and, as a result, the ability to keep interest rates around 3 percent (the same as in Chile) below those in Columbia and Peru.

Aside from business problems, the amount of people living in poverty in Mexico increased from 49 million in 2008 to 53 million in 2012. In addition, Mexico came in last of the 34 countries examined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD for inequality. The combination of poverty and inequality on the ground, plus incoming instability on a business and banking basis could prove a disastrous mix in Mexico (and in the US) in the face of possible rising interest rates, a strengthening dollar in the near-term, or enhanced volatility.

EM Debt Defaults and Bond-Stock Divergence

Credit default risk looms as well. The amount of corporate and bank debt issued since the Fed embarked on its zero-interest rate and QE policy and pushed it on the world, has escalated. Thus, rising interest rates or corporate defaults in the US would impact Mexican (and other EM) corporate bond prices and default rates.

The divergence between credit-risk as reflected by rising high-yield bond spreads (up from seven year lows in mid-2014) and equities is predominantly predicated on the 60 percent drop in oil prices this year, which as of August 20th, hit a six and a half year low. The energy sector represents 15 percent of the high yield market.

Energy stocks have dropped nearly thirty percent. If commodity prices continue falling, other sectors and the stock markets would be more effected. Countries reliant on oil revenues, such as Mexico where 30 percent of the federal budget is based upon them, are impacted directly from profit loss and secondarily by defaults. (Source)

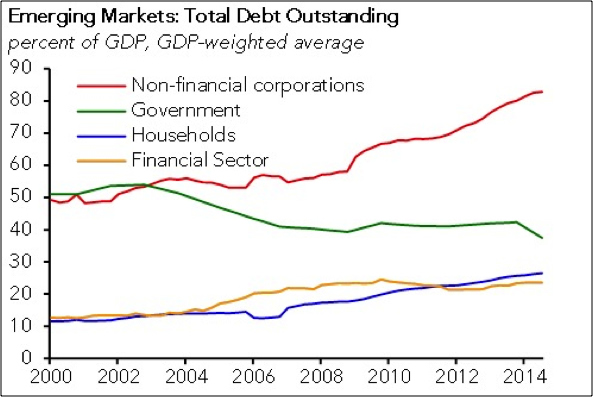

According to a recent report issued by the Institute of International Finance, “Corporate Debt in Emerging Markets: What should we be worried about?”, emerging market (EM) non-financial corporate debt rose to a record high of 83 percent of GDP, up from 67 percent in 2009. The total size of the EM non-financial corporate bond market has more than doubled to $2.4 trillion in 2014 vs. 2009.

Between 2015 and 2017, about $645 billion of that debt is set to mature with US dollar denominated bonds comprising $108 billion of that figure. Meanwhile, the volume of non-performing loans and general debt payment burdens have risen on US dollar strength, meaning EM banks, particularly those exposed to high degrees of foreign-currency lending, are increasingly in trouble.

Figure 1 – Source: BIS, IMF, OECD, McKinsey, IIF; Brazil, China, Czech Rep., Hungary, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey.

The low or zero interest rate policies from the FED, ECB and even EM central banks have propelled this issuance, particularly in the EM non-financial corporate segment, even in countries where public debt issuance hasn’t also skyrocketed.

Of the $1.7 trillion EM in non-financial corporate debt raised since 2009 in the international markets, about 30 percent ($510 billion) was in foreign currency, 80 percent of that ($430 billion) was in US dollars. The more reliant on external borrowing, the less stable a borrowing country’s financial situation becomes, and the more prone its firms are to downgrades or defaults as a result of external or internal weakening.

The report notes that higher foreign-currency risk exists in countries like Brazil, Mexico and Korea. In addition, a number of EM countries are holding cash reserves in domestic bank accounts from large percentages of proceeds raised offshore. They would be forced to withdraw from these funds to support currency weaknesses to service debt, which could increase the funding risk of EM banks.

What This All Means

This level of global inter-connected financial risk is hazardous in Mexico, where it’s peppered by high bank concentration risk. No one wants another major financial crisis. Yet, that’s where we are headed absent major reconstructions of the banking framework and the central bank policies that exude extreme power over global economies and markets, in the US, Mexico, and throughout the world.

Mexico’s problems could again ripple through Latin America where eroding confidence, volatility, and US dollar strength are already hurting economies and markets.

The difference is that now, in contrast to the 1980s and 1990s debt crises, loan and bond amounts have not just been extended by private banks, but subsidized by the Fed and the ECB. The risk platform is elevated. The fall, for both Mexico and its trading partners like the US, likely much harder.

This is a good example of how the Fed should be interested in its effects on emerging markets.

Poverty and climate change have led to increasing Mexican and Latin American refugees at the violent, narcoeconomy, militarized southern border of the US where we have drones and 700 miles of fence on a 2000 mile border.

This is not the sort of background that will deal well with increasing pressures.

Central banks and government fiscal policy need to realize that there are bigger problems than housing and stock market prices.

Well, here’s your recovery folks…”The US Federal Reserve buying program, though officially over, has rendered the Fed the largest hedge fund in the world, with a $4.5 trillion book of securities, more than a dozen times the figure of seven years earlier. The mortgage backed securities component remains at about $1.5 trillion, up from zero seven years ago.” So who’s buying pesos? seems like fertile ground for the worst of the worst

It’s always been tough in Mexico. All the way back to Montezuma. Even before that! Even the Mayans Even before that it was tough. It”s tough now. It’s almost like nothing has changed in 1000 years. It makes you wonder if “The Asteroid” would hit anyway, no matter what the banks did or didn’t do. That’s a weird thought if you think about it. And if you think about it, you think it wouldn’t be a single huge asteroid if the banks were taken out of the picture. It would be lots of little ones, like hail. it makes you wonder what the relationship is between banks, asteroids and hail. Pretty soon you start thinking in metaphor and it all makes sense in a way that involves the ideas of mass, gravity, supernovas and blackholes applied to the fabric of consciousness instead of space and time and matter. “What’s the matterr? Oh, never mind.” hahahahah’ that’s a joke I mmade up. But anyway, nobody will believe you if you try to tell them. They’ll think your nuts or at least deranged. Oh well. What difference does it make? Somebody probably thought something like that in Mexico 1000 years ago and look what happened anyway.