Yves here. The wee problem with this analysis, as useful as it is, is that it ignores the significance of assets held in secrecy jurisdiction, which Gabriel Zucman estimates at a whopping 6% of world GDP.

By Facundo Alvaredo, Research Fellow, Paris School of Economics; Tony Atkinson, Professor at the London School of Economics; and Salvatore Morelli, Post-doctoral fellow at CSEF. Originally published at VoxEU

The concentration of personal wealth has received a lot of attention since the publication of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. This column investigates the UK and finds wealth distribution to be highly concentrated. The data seem to suggest that the top wealth share has increased in the UK over the first decade of this century.

The concentration of personal wealth is now receiving a great deal of attention after having been neglected for many years. The much discussed book by Thomas Piketty, Capital in the 21st Century, stirred up an astounding debate across the world due to his dystopic vision of a future world where wealth will be more and more concentrated within the hands of a small elite that will perpetrate its own power by passing on enormous fortunes and advantages to the select few of the following generation.

Piketty urged governments to take steps to prevent this from happening. As argued by Ravi Kanbur and Joseph Stiglitz in a recent Vox column (Kanbur and Stiglitz 2015), the increase in wealth we observe nowadays stems in part from the increase in rents which “once created will provide further resources for rentiers to lobby the political system to maintain and further increase rents”. The surge of interest in wealth distribution is additionally justified by the recognition that, in seeking to understand the determinants of rising income inequality, we need to look not only at wages and earned income but also at income from capital, particularly at the top of the distribution.1

But how much do we actually know about wealth concentration at the top and how it is changing today? In a new paper (Alvaredo et al. 2015), we look at the UK – a country where the wealth distribution has long been studied – and ask three questions:

• What is the share of total personal wealth that is owned by the top 1%?

• Is wealth much more unequally distributed at the top than income?

• How far is wealth concentration increasing in the 21st century?

Our central theme is that there are different sources of evidence about wealth concentration, each with strengths and weaknesses. To some extent they tell similar stories, but there are also key differences, and these differences explain in part the reasons why the subject has given rise to controversy.

Estate Data-Based Estimates

First of all, the administrative tax data on estates at death can indirectly provide evidence about the wealth of living individuals, by which we mean the value of the total assets owned by individuals, net of their debts.2 This is achieved by applying (the inverse of) mortality multipliers differentiated by age, sex and wealth class. These data provide unique coverage of the wealth holders at the top but tax data are also affected by tax evasion and avoidance and the estate-based estimates rests on the reliability of the multipliers.

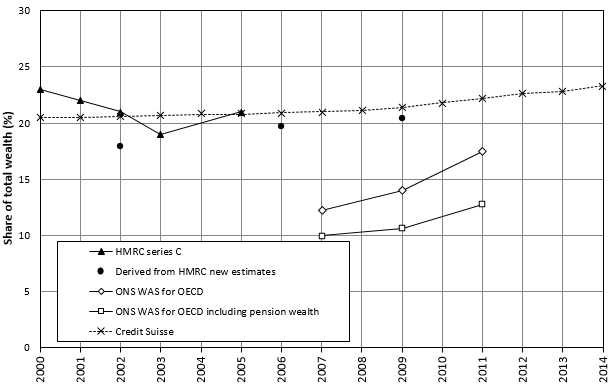

In the UK, the official HMRC Series C was estimated using the estate multiplier approach, up until 2005. The share of the top 1% is shown in Figure 1. In 2005 the series was replaced by a new data series focusing exclusively on the identified wealth (note that only estates submitting an inheritance tax return are captured – estates of low value are generally excluded, as well as those held in trusts or in joint names passing to a surviving spouse or civil partner).3 In particular, adjustments were no longer made for excluded wealth, for inappropriate valuations, and to a balance sheet basis. The estimates labelled ‘derived from HMRC new series’ in Figure 1 show a smaller top wealth share for the period of overlap.

Figure 1. Estimates of the top 1% wealth shares in the UK since 2000

Note: the WAS estimates relate to households and to Great Britain.

These UK estate-based estimates indicate that the distribution of wealth is highly concentrated. The top 1% own between one fifth and one quarter of total personal wealth. Second, the share of the top 1% in total net worth (of individuals) is around double the share of the top 1% (again, of individuals) in total net income (income after deducting income tax), which in the first half of the 2000s was around 10%.4 Thirdly, there is some indication that the top shares in wealth were increasing between 2001-2003 and 2008-2010.

Investment Income-Based Estimates

A quite different approach is to multiply up investment income reported in income tax returns to give an estimate of the underlying wealth. The investment income method, like the estate method, has a long history and was investigated extensively in the UK in Atkinson and Harrison (1978). Use of the method has been revived in the US by Saez and Zucman (2014). They apply yield multipliers, differentiated by asset class, to administrative tax data on different types of investment income in order to estimate the wealth holdings. We are exploring the possible use in the UK of either their method or that adopted in the 1970s by Atkinson and Harrison. However, it requires more detailed information than is currently publicly available either on investment income by category or on the classification of assets by types.

Household Survey-Based Estimates

Representative household surveys can provide direct evidence of personal wealth within the population. Figure 1 shows the estimated share of the top 1% for Great Britain (i.e. the UK excluding Northern Ireland) based on the Wealth and Assets Survey as supplied to the OECD by the ONS. These shares differ from those obtained using the estate data in that they relate to household wealth (rather than individual wealth), and are shown including and excluding pension rights.

The first finding is that, in the case of the overlapping period 2008-2010, the Wealth and Assets Survey estimates excluding pension wealth suggest a share of the top 1% that is considerably below the estate-based estimates: 14% for the top 1%, compared with 20%. These estimates are household-based and the geographic coverage differs, but the difference is larger than could be explained in this way. One has to ask how far the top shares may be under-estimated as a result of differential non-response to the household survey. The response rate to the first wave was 55%. It is also the case that business assets were excluded from the Wealth and Assets Survey estimates of total wealth, an omission that is likely to be particularly important in the upper wealth ranges.

The second finding is that the household survey-based estimates supplied by the ONS to the OECD show a distinct upward trend. The share of the top 1% in 2010-2012 is 2.7 percentage points higher than in 2006-2008 when measured including pension wealth, and the increase is nearly double (5.3 percentage points) for the estimates excluding pension wealth. Such a striking conclusion needs to be investigated further.

Combined with the Rich Lists

Lists of large wealth-holders, such as the Forbes List of Billionaires or the Sunday Times Rich List for the UK, can also provide useful estimates for the share of total wealth owned by the wealthiest individuals. The rich lists provide information on the shape of the upper tail of the wealth distribution that allows for a more detailed investigation of the distribution within the top one percent. To date, official estimates of wealth concentration have not shown shares for groups smaller than the top one percent. The Sunday Times Rich List for 2010, for example, has 1,000 people with £335.5 billion. These make up 0.004 per cent of total Great British households and 5.3% of total Wealth and Assets Survey non-pension wealth. However, such data do not necessarily guarantee the representativeness of the sample and often use different definitions of units of analysis as well as geographical coverage of wealth holdings.

There are in addition synthetic estimates that draw on two or more sources, carried out by Davies and Shorrocks in the estimates they have prepared for Credit Suisse (Credit Suisse Research Institute 2014). In effect, they use the total number of UK billionaires (but not their wealth) reported in the Forbes list to fit a Pareto distribution. The changing number of billionaires drives the year-to-year changes shown in Figure 1 (the dashed series), since the distribution is otherwise based on the Wealth and Assets Survey 2006-2008. As may be seen, their estimates suggest that the share of the top 1% is close to the estate-based estimates, and the share has increased by some 3 percentage points over the period 2000-2014.

Wealth distribution is often highly concentrated and the UK is clearly no exception. The estate-based estimates certainly suggest that individually held wealth is more concentrated than individual gross incomes. Moreover, our estimates provide some support for the view that the top wealth share increased in the UK over the first decade of the present century.

However, the evidence about the UK distribution of wealth post-2000 is far from complete. Significant investment is necessary if we are to provide satisfactory answers for the UK to the three questions with which we began. There needs to be a re-examination of the estate method in the light of 21st century circumstances. HMRC estate-based estimates should be continued and improved and data need to be made available to allow use of the investment income method to be properly assessed. There also needs to be a reconciliation of the differing pictures shown by the estate estimates and household surveys regarding top wealth-holdings, and the potential of rich lists can be more fully exploited.

See original post for references

I like this article a lot. Comparisons between models are really useful in showing the effects of assumptions and what is being missed.

Consistent bias, for example. When my wife’s paycheck kept getting shorted, the employer called it random error, but in fact it was biased. Global warming models often fail to match with observed increases, which indicates the models are incomplete. When available information keeps lowballing observed values, then the model is missing something, &/or the information is biased.

There are (at least) two problem intractable. The first is the ‘secrecy jurisdiction’ which means that energy and money are being spent to hide the numbers, but assumes that the numbers are hard and accountable.

Another is a slippery one, like the effects of cognitive capture. It has to do with information and externalities. Mary Odum said, money is a circular flow of information that flows in a circle in the opposite direction from the flow of energy and goods. It’s an insufficient definition but useful. The farther up the chain, the further the money is from the hard numbers of productivity. The Magic Money Wand of Fiat seems to have unhooked money from tangibles almost altogether; when derivatives have ‘value’ an order of magnitude over the underlying assets, and jus primae noctis, then the cash can support the value of the underlying assets and the froth of bubbles seems self-sustaining.

It seems the farther up the chain, the more abstract and intangible the subject, the fuzzier the numbers. Calculating an EROEI for solar panels is tricky. Do you just follow the cash? Do you add externalities like pollution? How about pollution you don’t know about, the way endocrine disruptors in the water supply were acting before there was knowledge of the effect? Do you amortize the opportunity costs?

I’ve read that the business of Wall Street is insider information. How do you value the knowledge of knowing the very moment to dump the stock?

Thanks for the article, these thoughts are riffing on the theme, and I find my understanding insufficient in a necessary conversation.

It is easier to see what is going on if we put things in a historical perspective.

Is Capitalism the first social system since the dawn of civilisation to trickle down?

Since it is based on self-interest this seems highly unlikely.

It would be drawn up in the self-interest of those that came up with the system, i.e. those at the top.

The 20th Century saw progressive taxation to do away with old money elites and so looking at the playing field now can be rather deceptive.

Today’s ideal is unregulated, trickledown Capitalism.

We had unregulated, trickledown Capitalism in the UK in the 19th Century.

We know what it looks like.

1) Those at the top were very wealthy

2) Those lower down lived in grinding poverty, paid just enough to keep them alive to work with as little time off as possible.

3) Slavery

4) Child Labour

Immense wealth at the top with nothing trickling down, just like today.

The beginnings of regulation to deal with the wealthy UK businessman seeking to maximise profit, the abolition of slavery and child labour.

At the end of the 19th Century, with a century of two of Capitalism under our belt, it was very obvious a Leisure Class existed at the top of society.

The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions, by Thorstein Veblen

The Wikipedia entry gives a good insight.

This was before the levelling of progressive taxation in the 20th Century.

It can clearly seen that Capitalism, like every other social system since the dawn of civilisation, is designed to support a Leisure Class at the top through the effort of a working and middle class.

After the 20th Century progressive taxation the Leisure Class probably stay hidden in the US. In the UK, associates of the Royal Family are covered in the press and show the Leisure Class are still here with us today.

It was obvious in Adam Smith’s day.

Adam Smith:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

With more modern Capitalism it’s better hidden:

The Rothschild brothers of London writing to associates in New York, 1863:

“The few who understand the system will either be so interested in its profits or be so dependent upon its favours that there will be no opposition from that class, while on the other hand, the great body of people, mentally incapable of comprehending the tremendous advantage that capital derives from the system, will bear its burdens without complaint, and perhaps without even suspecting that the system is inimical to their interests.”

Wow, that Rothschild quote predates Das Kapital by four years.

Amazing the truths the rich may say when trump’ting their own advantages.

+ wow. We might be the great unwashed, but we sense our illnesses. I think we need at least a new umbrella. I’d like to see the UN pass a declaration of the Sovereignty of the Planet – since it is the final word on everything – and the word was good. So that we establish the Earth as Sovereign. Then all interested parties can join in the distribution of Planet Sovereigns but they cannot directly profit from them – the new currency to be spent in the restoration and maintenance of the planet. And committeed by scientists and sociologists and ecologists and biologists and botanists – you get the picture. And no money spent is an indebtness, rather an asset; capitalism upside down. And even if it were somehow considered a debt in some aspect, it doesn’t matter. Because profit, as we know it, is not at stake bec. it is totally obsolete.

other susan: Few of power seem to be interested in restoring or maintaining

our planet home, much less preserving it. So long as humans rule, it will be

so. We can’t change our hard wiring.

The pre-Columbus Indian Nations maintained their part of the planet home, and upgraded and terraformed large parts of it. If humans are hard wired, how did those two continent-loads of people overcome the hard wiring?

I wonder about that quote. In a quick internet search I could not find any further documentation, any listing of the complete letter, etc. It has the ring of a lot of Lenin, Lincoln, and other quotes which turned out to be imaginary.

Every citation is exactly the same.

Can anyone locate the whole letter…or find a reliable scholarly work that cites it?

Whether or not traceable to Rothschilds or anyone else, it’s kind of hard to argue that the content pretty accurately describes how things work. Along with that other bit about he who controls the money supply, controls the nation, and as BIGness happens, eventually most of the planet except for the few who can somehow remain “unbanked.” Which the Money Economy is working to ensure that even impoverished Africans can be admitted to the “banked” via cell devices that let them play low person on the Banked Totem Pole. To which so much stuff trickles down. And as with Haida poles, eventually the bottom rots off, but the shamans just carve and erect another for the mopes to honor and obey…

As noted by DW, there’s hardly a citation plus evidence to be found that this text was authored by people who actually did the stuff that’s described in the annals of the banking of the world. One interesting link, with cavils: http://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/sociopolitica/pawns_inthegame/pawns_05.htm Who knows anything for sure and certain, in a world of deceit and corruption and moral hazard and false flags and all the rest? But look around — even at the stuff that appears in NC’s posts and commentary. Are the statements anything but true, in application and practice?

I did a little research.

The letter quoted by Keith is almost certainly not authentic. Never written by the “Rothschild brothers.” There is not a single source. Just the same quote over and over in questionable places.

JT McPhee below, makes reference to the most famous Rothschild “quote” on he who controls the money supply controls the government. there is no evidence to link it to Rothschild.

Many sources debunk this one.

Two of the best are:

http://history.stackexchange.com/questions/7887/did-rothschild-say-this-famous-quote-if-yes-what-did-he-mean-by-it

http://www.illuminatirex.com/conspiracy-misquotes/

Another famous quote, attributed to Rothschild….”buy, when there is blood in the streets.”

Also false.

http://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2013/04/waxing-rothschild.html

There is an industry of false quotes, almost always right wing inventions which live on in their speeches and writings. The letter cited by Keith with its contempt for working people has the odor of stemming from extreme right wing movements with the target being the Jewish bankers. The quote cited by JT McPhee also has the odor of fascism. The giant industrialists who control the means of production are not part of the equation. Just the bankers.

History shows us the profit motive will lead to all sorts of horrors.

1) I need cheap labour to work on my sugar plantations to maximise profit.

Slavery, ideal.

2) I need cheap labour to work in my factories to maximise profit.

Men, women and children all paid enough just to keep them alive to work.

3) They came up with the Enclosures Acts to take away the Common Land of the people, leaving landless peasants who could no longer provide for themselves.

They now were in need of wages and ripe for exploitation in the factories and on the farms of the wealthy.

Today where regulation is lax:

Apple factories with suicide nets in China.

Apple profits come first.

To see the wealthy as generous benefactors would be a huge mistake.

Apple profits come first.

To see the wealthy as generous benefactors would be a huge mistake.

The monetary system is designed to give the bankers a cut at every stage in the process, but somehow these bozos still manage to go bust when they can create the money out of thin air and charge interest.

It was collective labour movements and not capitalism that got the masses a larger slice of the pie.

The rich give nothing freely.

Total agreement with Keith!

Absolutely: the rich give up nothing without a struggle.

Of course, while the financial sector is huge….it is characteristic of ultra right/fascist movements to focus exclusively on international bankers (aka Jews) as the villain. The bankers are of course a pernicious force, but those who control natural resources and means of production are often the natural allies of the ultra right. (Koch)

When climate change reaches its peak in storms, floods and droughts then the wealthy and the poor will be equally affected and money will mean little. At that time, perhaps, we can start again from a state of true equality.

That would be nice, but I think that if the rich become adversely affected they will simply go someplace nice and leave the rest of us to drown/scorch/starve/kill each other/be killed by the forces of ‘law and order’. EG, New Orleans and Katrina, gated communities anywhere, gun-packing concierges in hi-rise condos…

If we want equality of opportunity we should think what a meritocracy would look like.

“What is a meritocracy?”

1) In a meritocracy everyone succeeds on their own merit.

This is obvious, but to succeed on your own merit, we need to do away the traditional mechanisms that socially stratify society due to wealth flowing down the generations. Anything that comes from your parents has nothing to do with your own effort.

2) There is no un-earned wealth or power, e.g inheritance, trust funds, hereditary titles

In a meritocracy we need equal opportunity for all. We can’t have the current two tier education system with its fast track of private schools for people with wealthy parents.

3) There is a uniform schools system for everyone with no private schools or universities.

Thinking about a true meritocracy then allows you to see how wealth concentrates.

Inheritance and trust funds are major contributors.

When you start off with a lot of capital behind you, you are in life’s fast lane.

a) Those with excess capital invest it and collect interest, dividends and rent.

b) Those with insufficient capital borrow money and pay interest and rent.

If the trust fund/inheritance is large enough then you won’t need to work at all and can live off your rentier income provided by your parents wealth and the work of an investment banker.

If you are in life’s slow lane, with no parental wealth coming your way, you will be loaded up with student debt, rent, mortgages and loans.

To ensure the children of the wealthy get the best start we have private schools and universities to ensure they get the best education and make the right contacts ready for the race of life.

The children of the poor are born in poor areas where schools are typically below average and they are severely handicapped before they have started the race of life.

Wealth concentrates because the system is designed that way.

A meritocracy gives everyone equal opportunity but that is the last thing those in charge want for their children

The champions of Capitalism, the US and UK, have really low social mobility.

They are both about the same, which is a level that is the second worst in Europe.

A privately educated elite is obvious in the UK, the US hides its rigid class structure much better.

Capitalism works in the way its supposed to work.

So you like meritocracy? Be careful what you wish for.

Two books from the ’90s, ‘The Revolt of the Elites’, and ‘The Bell Curve,’ one coming from the left (Christopher Lasch, published post-humously), and one from the right (Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein) reached the same conclusions: that our increasingly meritocratic society was hollowing out the center and producing a cognitive elite that was garnering the biggest paychecks and the most power. The cognitive elite is not exactly patriotic, and tends to be pretty international in focus. Smart kids who might have joined their dad’s union a generation ago now work for Goldman-Sachs. So not only is the kid pressed to become a money shark in the shark tank, but the union is deprived of someone with leadership potential and natural intelligence.

Redistribution plans like Piketty’s will go nowhere, because by and large the cognitive elite earns their money rather than inheriting it. The children and grandchildren of one of the world’s great investors, Shelby Cullom Davis, all became very rich despite inheriting little. Why? Because they had brains and connections, and these are lots more important than capital.

Brains polished in expensive schools and social connections to your ancestors’ super rich super powerful friends are indeed capital. And leverage-ably monetizable.

It would be in the interests of the elite to dismiss meritocracy so they an carry on tilting the playing field for their own children.

If they can feed this propaganda to the Left and Right, the case for a meritocracy should be dealt with.

Social mobility figures for the US and UK show they are no meritocracies with really bad social mobility figures. Strangely they are almost the same and are at a level that would be the second worst in Europe.

The City in the UK is well known for being privately educated, there is no meritocracy there.

They have fooled you into thinking you live in a meritocracy to use some meritocratic ideas:

We don’t tax the rich too much because they have earned their wealth and they deserve to keep most of it.

Those at the bottom are there through their own lack of effort and don’t deserve benefits.

We have meritocratic ideas without a meritocracy, the worst of both worlds.

You have an example ….. Shelby Cullom Davis …… if I find someone who is 80 years old and smokes 40 a day, will you think smoking is safe.

Are you familiar with Gaussian/Bell Curve distributions, there are always exceptions at the edges of the bell curve.

I assume you must be by the book you quote ….. do you understand the concept?

The OECD social mobility study:

http://www.oecd.org/centrodemexico/medios/44582910.pdf

Cervantes said it well before the Rothschilds and Marx. “… the haves and the have-nots.”

Enjoyed the piece. One thing I would add is that from the perspective of policy advocacy, there is a bit of a false sense of precision going on. It’s impossible to know exactly how much wealth the top 1% have because the concept of wealth itself is not an independent variable of value judgments within political economy. The very act of converting everything to a common denominator of the present value of a national currency unit involves subjective as well as objective means. How much is flying your closest friends and family to a private island for your wedding “worth” in USD or GBP?

And that’s okay, because we don’t really need to know. Knowing that there is too much concentration of wealth is sufficient for the broad policies of progressive income taxation, ending the wars, reducing the prison population, stopping corporate welfare, and so forth.

It is not a matter of inadequate information. It is a matter of conscious choice: a difference in preferences since so many educated people in the Anglo-American world rather like inequality. And that’s the rub. A lot of people who aren’t in the top 1% actively work against a more egalitarian society.