Lambert here: AI seems to be having a moment.

By Masayuki Morikawa, Vice President, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI). Originally published at VoxEU.

The substitution of human labour by artificial intelligence and robots is a keenly debated topic. Some claim that a substantial share of jobs is at risk, while others argue that computers and robots will lead to product innovations and hence to unimaginable new occupations. This column uses a survey of Japanese firms to examine the impact of AI-related technologies on business and employment. Overall, firms expect a positive impact on business but a negative impact on employment. Firms with a highly skilled workforce, however, have a more optimistic view than firms with lower skilled employees.

Since the second half of the 1990s, productivity growth has accelerated in the US due to the Information Technology (IT) Revolution. However, the productivity effects of traditional types of IT were exhausted by mid-2000 (e.g. Fernald 2015). Today, the impacts of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics―referred to as the Fourth Industrial Revolution―on the future economy and society is attracting attention, and many speculative arguments have arisen regarding the possible effects of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In particular, the substitution of human labour by AI and robots is being hotly discussed.

The Japanese government has begun efforts to develop and diffuse AI and robotics technologies. The Robot Revolution Initiative Council was established in 2014 and has published a report, New Robot Strategy, which includes a five-year action plan to realise the robot revolution. The Artificial Intelligence Research Center was established in the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) in 2015 to promote development of AI-related innovations. The Japan Revitalization Strategy 2016, which is the core growth strategy of Abenomics, places the Fourth Industrial Revolution at the top of the growth policy agenda.

The Impact of AI and Robotics on Employment

There have been numerous studies on the complementarity/substitutability of IT and the skills of workers. Earlier studies have presented evidence based on the skill-biased nature of IT that indicate skilled labour and IT are complementary, but that unskilled labour and IT are substitutes. More recent studies have shown that IT substitutes for routine tasks conducted by middle-skilled workers, which results in the polarisation of the labour market. Although the discussion about the impact of AI and robotics on employment is a natural extension of the studies on the relationship between IT and labour, quantitative evidence on this issue has been scarce.

The estimation by Frey and Osborne (2013) of the number of jobs at risk to be replaced by future computerisation, including advances in machine learning and mobile robotics, has attracted attention of the media and policy practitioners. According to their study, roughly 47% of total US employment is at risk from computerisation.

On the other hand, Mokyr et al. (2015) survey the historical lessons learned since the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century and argue that computers and robots will create new products and services and that these product innovations will result in unimaginable new occupations. However, we cannot deny the possibility that the impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution is different from the past innovations.

Evidence from a Firm Survey

Against this background, we designed and conducted an original survey of Japanese firms to investigate the impact of AI and robotics (see Morikawa 2016 for details). Specifically, in late 2015, we distributed the Survey of Corporate Management and Economic Policy to a variety of firms operating in both the manufacturing and service industries and obtained more than 3,000 responses. The survey inquiry was wide-ranging, but in this column we focus on the questions about the possible impact of AI and robotics on business and employment. Special attention is paid to the relationship between the skills of human resources and AI-related technologies.

Responses regarding the impact of the development and diffusion of AI and robotics on future business were generally positive – positive responses (27.5%) far surpassed negative responses (1.3%).1 In contrast, the perception of the impact of AI and robotics on employment is negative – 21.8% of firms responded that the development and diffusion of new technologies will decrease the number of employees, and the share of firms expecting positive effects on their employment is notably small (3.7%).2

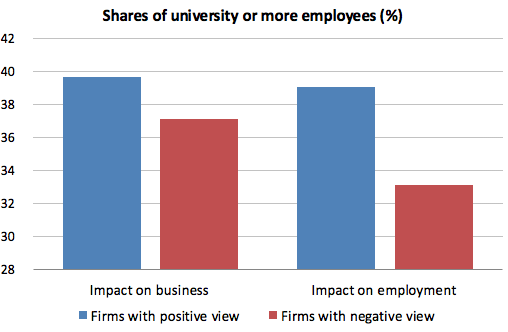

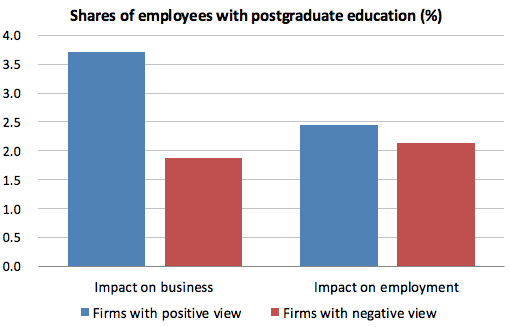

Lessons learned from the IT Revolution are that firms with relatively low-skilled employees are likely to be affected negatively by the new industrial revolution, and those with highly skilled employees tend to reap benefits. To analyse this technology-skill complementarity in the context of AI, we compare the relationship between firms’ perceptions of the impact of AI and robotics and the education levels of their employees (see Figure).

Figure 1 Firms’ views on the impact of AI-related technologies and employee skill levels

Source: Calculated from the Survey of Corporate Management and Economic Policy (RIETI).

Firms expecting positive effects of AI and robotics on their business have significantly higher ratios of university graduates and employees with postgraduate degrees. Conversely, the ratio of highly educated employees is lower among firms that anticipate a negative impact of AI and robotics on their employment. This technology-skill complementarity is confirmed by formal estimations controlling for other covariates including firm size and industry.

According to a previous study, the return to postgraduate education in Japan already exceeds 10% (Morikawa 2015). The diffusion of AI and robots may further raise the return to higher education unless changes in the education system catch up with the technological progress. In order to accelerate the development and diffusion of AI-related technologies and, at the same time, maintain employment opportunities, it is necessary to upgrade human capital, such as increasing the number of people with postgraduate education.

Editors’ note: The main research on which this column is based appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Fernald, J.G. (2015), “Productivity and Potential Output before, during, and after the Great Recession,” in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2014, edited by J.A. Parker, and M. Woodford. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1–51.

Frey, C.B., and M.A. Osborne (2013), “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” mimeograph, Oxford Martin School.

Mokyr, J., C. Vickers, and N.L. Ziebarth (2015), “The History of Technological Anxiety and the Future of Economic Growth: Is This Time Different?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29, 31–50.

Morikawa, M. (2015), “Postgraduate Education and Labor Market Outcomes: An Empirical Analysis Using Micro Data from Japan,” Industrial Relations 54, 499–520.

Morikawa, M. (2016), “The Effects of AI and Robotics on Business and Employment: Evidence from a Survey on Japanese Firms,” RIETI Discussion Paper, 16-E-066.

Endnotes

[1] 71.3% of the firms responded as “neither positive nor negative.”

[2] 28.6% of the firms expect “no impact” of AI and robotics on their employment and 45.8% of firms responded as “don’t have any idea.”

Who is gullible enough to believe in a robot economy, artificial intelligence and quantum computing?

Pay attention and you’ll see that everyone is doubling down on reliable human slaves

Sure, by and large the high-education companies are the ones making AI. Of course they have higher employment education. That is anecdote not meaningful correlation.

http://www.scmp.com/news/china/economy/article/1949918/rise-robots-60000-workers-culled-just-one-factory-chinas

Excerpt:

Thirty-five Taiwanese companies, including Apple’s supplier Foxconn, spent a total of 4 billion yuan (HK$4.74 billion) on artificial intelligence last year, according to the Kunshan government’s publicity department.

“The Foxconn factory has reduced its employee strength from 110,000 to 50,000, thanks to the introduction of robots. It has tasted success in reduction of labour costs,” said the department’s head Xu Yulian.

“More companies are likely to follow suit.”

As many as 600 major companies in Kunshan have similar plans, according to a government survey.

Foxconn has a million+ employees and manufactures around 40% of consumer electronics. This is a foot in the water. Wonder how this ties in:

> In 2015 Foxconn announced it would be setting up twelve factories in India and would create around one million jobs

They should worry more about “knowledge workers” than “workers” in my opinion. The kind of AI pioneered by IBM (Watson) could clean up pretty much of the work in legal and engineering in just a decade. Chemistry AI’s are moving past the experimental stage and into industrial chemistry labs soon.

http://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2016/04/12/the-algorithms-are-coming

Logistics is already heavily AI’ed.

For decades some of us blue collar proles have been warning the knowledge workers and professionals that they were next. To deaf ears, natch….nothing as individualistic and libertarian as a keyboard jockey or E-school grad in the go-go 80s and 90s, when they were hiring anti-gravity engineers and warhead programmers by the boxcar load to win the cold war. And now here we are, and the meritocratic educated tech workers and STEM workers and professionals are looking down the barrel of the H1B visa and starting to sound like unemployed steel mill workers in 1986.

We told you so, Cold comfort, but it’s something. We. Told. You. So.

Sometimes they don’t have to divide-and-conquer us. We do it to ourselves.

It’s not “AI” it’s “algorithm”. A system of hidden, self-generated rules that classifies input based on how it was trained. It has to be trained first. If the training is good you get usable results. If not look out below.

What AI produces is crap: “good enough” for the poorly-run businesses of today who only care if things are cheap, not if they are right. It might be a situation similar to mass produced clothing that fits everyone equally poorly vs. the bespoke garments of a hundred years ago. Unless the managers came up through engineering they have no ability to communicate properly to AI. They don’t know how to train it. They don’t know what to ask for. And they will inevitably misuse the results in horrifying ways.

“Stop worrying about technological unemployment! You people will just transfer into new, fulfilling careers opened up by the rise of the robots–such as yoga teachers, massage therapists, baristas, sex-providers, gardeners and footmen to the wealthy!…” say the same voices that pushed NAFTA through.

We should believe them this time why?

If they said, “You people will just transfer into new, fulfilling careers opened up by the rise of the robots–such as wiping the butts of physically-impaired and very old people,” then you could believe them.

The only reason people panic about the loss of jobs is because capitalism stripped people from their land and made them completely dependent on wage labor. NC has many posts on this subject. The peasants are now loaded up with debt and reliant on the mass market for basic necessities. If that were not the case — if people had a place to live, no debt, and enough land to survive via horticulture etc. — we could welcome new technology with some complaisance.

Capitalists must explain how they intend to handle the issue of surplus workers. They broke the previous system, they reaped the profit, they own the solution. Technology requires far-flung supply lines incredibly vulnerable to disruption. Humans denied dignity, position, and basic survival are all to happy to provide it.

It’s going to be some kind of crappified basic universal income, obviously. Some sort of low-rent version of the Marxist post-work utopia, with everyone glued to Jersey Shore: Mare Imbrium to see who will get voted out of the airlock next and checking their facebook feeds in virtual reality instead of rearing cattle and philosophizing after dinner or whatever it was.

Robert W. McChesney and John Nichols in their new book, People Get Ready: The Fight Against a Jobless Economy and a Citizenless Democracy — New York, Nation Books, 2016, see AI as a very significant component of a confluence of factors auguring a deteriorating job picture in the coming years. They make a convincing argument that forthcoming advances in computer technology will, in the not too distant future, permit the automation of jobs that are currently thought of as professional.

This brings up a philosophical question I’ve thought about at times.

Some rambling here,

Let’s say machines, computers, robots advance to the point that most labor is unneeded. This would mean in theory that most of the population wouldn’t have to work. Sounds great on the surface! But what in today’s world “No Work” really means is “NO INCOME” and that means “POVERTY”, and all the ills that go with it.

So say in a society where the productivity of machines is so high that the need for labor is minimal, the question becomes: “How do we distribute wealth (productivity) for the benefit of everyone, but allow for individuality, and reward those that benefit society?” Really this question is no different than what we talk about here every day. “How should wealth be distributed?” By this I am aiming at one of FDR’s Four Freedoms, “Freedom from want”. For now we will ignore climate change and ecosystem limits which at least “in theory” put a ceiling on things.

Perhaps a robust guaranteed minimum income; and people who want to work could earn more, or pursue personal or artistic pursuits that could produce an income. How to reward extra effort fairly? I’m assuming there would still need to be human oversight, creativity and input into the system.

One big problem is what to do with those that need to have and control everything. I’ll call them what they are, “Psychopaths”.

So would we have something like the movie Elysium, rich enclaves with a small tech class, including a few managers and human enforcers, or something more along the lines of Star Trek’s Federation?

Three comments:

1. “In theory… most of the population wouldn’t have to work.” This is not just you but I don’t understand what people are saying when they say this. Any look at our “best ever” country shows lots of work that needs to be done: infrastructure is falling apart, many public schools are understaffed (imagine what 4 or 5 teacher’s aides in every classroom could do), many places still suffer from severe shortages of nurses, home health care aides, etc. And, as you say, this is without considering the need to address climate change, which should be the employment program to end all employment programs. So I think the starting concept needs to be interrogated much more closely. Or perhaps the claim is more specific than the current verbiage.

2. I am open to other interpretations but at this point in time, I think the question you are asking is: what do we do when there isn’t enough paid work for everyone? But, despite the recent scare stories about AI, this is certainly not a new dilemma and the last century (two centuries if we are going back to Speenhamland) provides considerable thought, practice, and analysis of this condition and efforts to remedy it. Not that new thinking isn’t needed. But I find the claim that we are confronting an(other) “end of history” situation misleading in the extreme.

3. I tend to go on and on about care work. In addition to the specific travails of older and disabled people who don’t have relatives available to provide uncompensated care for/to them, we generally do a sh1tty job in this country caring for all people who need care – young, old, and all those in between with care needs. Some have claimed to me that these aren’t “jobs” and others, more theoretically, that commodifying care work might be a less good strategy than de-commodification (perhaps in the form of a UBI that would allow more people to do unpaid care work). I await their proposals. In the meantime, it seems to me that a program that paid people the new federal minimum wage of $15/hour to do care work, including caring for their own children and elders, accompanied by appropriate (paid) care training/education, could address many of these issues at once in a holistic manner.

Avoiding the Lump of Labour Fallacy and Broken Windows Economic Policy

“Firms expecting positive effects of AI and robotics on their business have significantly higher ratios of university graduates and employees with postgraduate degrees”

What does China do?

Xi calls for building competitive human resource system http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-05/06/content_25118308.htm

China university rule change sparks protests in 4 provinces https://next.ft.com/content/6a6c8b18-20be-11e6-aa98-db1e01fabc0c

Literacy

The original argument for simplification was that it would accelerate the literacy process. That is why many now claim that given China’s improved economic and social conditions the use of simplified Chinese may not be necessary any longer.

http://www.counterpunch.org/2016/04/19/language-simplification-in-china-as-a-tool-of-progress/

“Lessons learned from the IT Revolution are that firms with relatively low-skilled employees are likely to be affected negatively by the new industrial revolution”

Hong Kong-based campaigner to press United States big business on slavery scourge

http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-crime/article/1965358/hong-kong-based-campaigner-press-united-states-big-business

The West is busy enjoying advance stage debt peonage

Neither Robots nor Slaves buy shit

Robots are great in controlled environments but try to pull an autobot and you’ll need a human watcher.

Hack a car in Michigan, go to prison for life if new bill becomes law http://www.computerworld.com/article/3064381/security/hack-a-car-in-michigan-go-to-prison-for-life-if-new-bill-becomes-law.html

In America’s prisons, a reinvented version of slavery lives on http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/09/prison-labor-in-america/406177/

Skynet is impossible, godel theorem, what is possible is stuff like genocide by drone by simply declaring any drone kill a terrorist, obama doctrine and other fudges, like mechanical turk or social engineering folks into classifying stuff

People Blindly Follow Their Robot Leaders http://nymag.com/scienceofus/2016/03/do-people-instinctively-trust-robots-too-much.html

Principal Component Analysis is not 42

But at least the ECB/BOJ/FED etc are making sure there’s money for hookers sloshing about

Thank you for your thoughtful reply,

A lot of what of what I’m thinking is purely speculative at this point. And yes I’m wondering what do we do when there is not enough work to go around. Pretty sure it won’t happen nearly as quickly as some think. Part of my work is fixing what the computers get wrong and making sure data gets from one system to another correctly, so from my point of view the day will not come soon. FYI (I had no idea until the other day, but I meet NC’s typical reader profile scarily close).

1. Yes, a lot of disinvestment needs to be re-invested here so to speak. Money is stuck up at the top of the pyramid and really needs to be pulled down and invested in projects that will benefit and employ people. Adding teachers and decreasing class sizes is one thing that works for me, but realize many of those running things in this country have no interest in an educated populace that can think for themselves.

2. Not an end of history situation from my perspective, but more about the choices we make going forward and whether we choose to value our world and the life on it. On other blogs I see a lot of AI/ productivity improvements being used as an excuse to justify screwing working people. TINA folks.

3. Home care can be physically and emotionally challenging and yet it is one of the least valued (by the all-knowing “Market” making it hard to find and retain good workers. And yes, we do a shitty job taking care of those that need care. Again about choices. This is one area where an increased minimum wage would benefit people. Finally, as I think Bernie proposed a large scale project for alternative energy would help with climate change and employee people. This should have been started decades ago imho.

TINA

Yep, lets focus more on digging virtual holes and filling them again as that is surely the way forward. We tried it with digging real holes but this is different….

What is so wrong with shorter work-weeks, longer vacations and earlier retirement?

And the cynic in me thinks that perhaps the way that MAINTAINS employment isn’t at all what you are supposed to assume, but rather is that it keeps people out of the labor force, until 30 years old or so.

But instead of trying to make everyone an academic, lets just have shorter worker weeks and longer vacations for all, natural academics types can find their calling that way as will everyone else.

Very interesting comments.

The last paragraph ; “The diffusion of AI and robots may further raise the return to higher education unless changes in the education system catch up with the technological progress. In order to accelerate the development and diffusion of AI-related technologies and, at the same time, maintain employment opportunities, it is necessary to upgrade human capital, such as increasing the number of people with postgraduate education.”

The USA public education system as an institution, has consistantly been challenged for the past 25 years by the billionaire funded Chater School movement .

Critics contend Higher Education in the USA has been “dumbed down” . Are we on the verge of “Factory Schools” 4th Indusrial Age style? “Gattacaesque”

I’ve been thinking about this passage a lot over the past few years.

Wrote Dorning Rasbotham in 1780:

Rasbotham’s glib dismissal of concerns about technology calcified into unquestionable economic dogma and 111 years later was given the sobriquet of the lump-of-labor fallacy.

Although the lump-of-labor may be a “fallacy,” its refutation is a myth. What is at issue — and has always been at issue — is NOT the total quantity of work to be done. The struggle is over proportions. Who gets how much of what in exchange for how much effort. The framing of the issue as being about the “quantity of labour to be performed” is a distraction and a diversion. As Thomas Pynchon wrote, “If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.”

Worrying about the amount of work to be done is the wrong question. But it is exactly the question THEY want you to be asking. Because then they don’t have to worry about answers to the proportionality question.

In 1662, John Graunt wrote:

Isn’t that the “same principle” that Dorning Rasbotham later said was false? It is not. And therein lies all the difference in the world. It is the difference between asking the wrong question and asking the right question. A certain proportion is not a certain quantity. A proportion is a relationship, a ratio.

Graunt’s concern with proportion is a legacy of Aristotle’s Politics and his Ethics. His “political arithmetick” was primarily concerned with understanding the political. In contrast, Rasbotham’s proto-political economy was primarily concerned with subsuming the political for the sake of the expansion of trade. John Ramsay McCulloch elevated this impulse of suppression in his footnote ode to the holy wisdom of Rasbotham’s straw-man edict:

No idea so groundless and absurd? Under any circumstances? McCulloch’s hyperbole is astonishing. But not as astonishing as his arrogance. What about the idea that quantity is all that matters and that proportions are of no consequence?

How do we get beyond the trade-trumps-policy treadmill that McCulloch’s and Rasbotham’s injunction inflicts upon economic discourse? How do we move from the quantity question to the proportions question? My suggestion is a technique called “ethical debate” that Anatol Rapoport outlined back in 1960 as a way of toning down the Cold War arms race. I will be writing a piece about my recent experiments with the technique in an exchange with Omar al-Ubaydli and will post it at EconoSpeak when it’s finished.