This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 918 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in financial realm. Please join us and participate via our Tip Jar, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our fourth goal, burnout prevention

By Maria Demertzis, a fellow at Bruegel and a visiting professor at the University of Amsterdam. She has previously worked at the European Commission and the research department of the Dutch Central Bank. Originally published at Bruegel

The attempt to address the problem of non-performing loans in the EU should tackle both sides of credit creation at once. On the demand side, new credit is not picking up as long as the problem of the debt overhang, namely the disincentive of undertaking new investments and consumption while old debts are prohibitively high, remains. This, hinders the creation of new productive capacity, necessary to absorb factors formerly misallocated to sectors hit by the crisis. By implication, as long as private debts remain at high levels, economic activity will struggle to pick up. On the supply side of credit, progress has been slow in resolving impaired loans, which persist in banks’ balance sheets. This is problematic for both their overall health but also the creation of new credit.

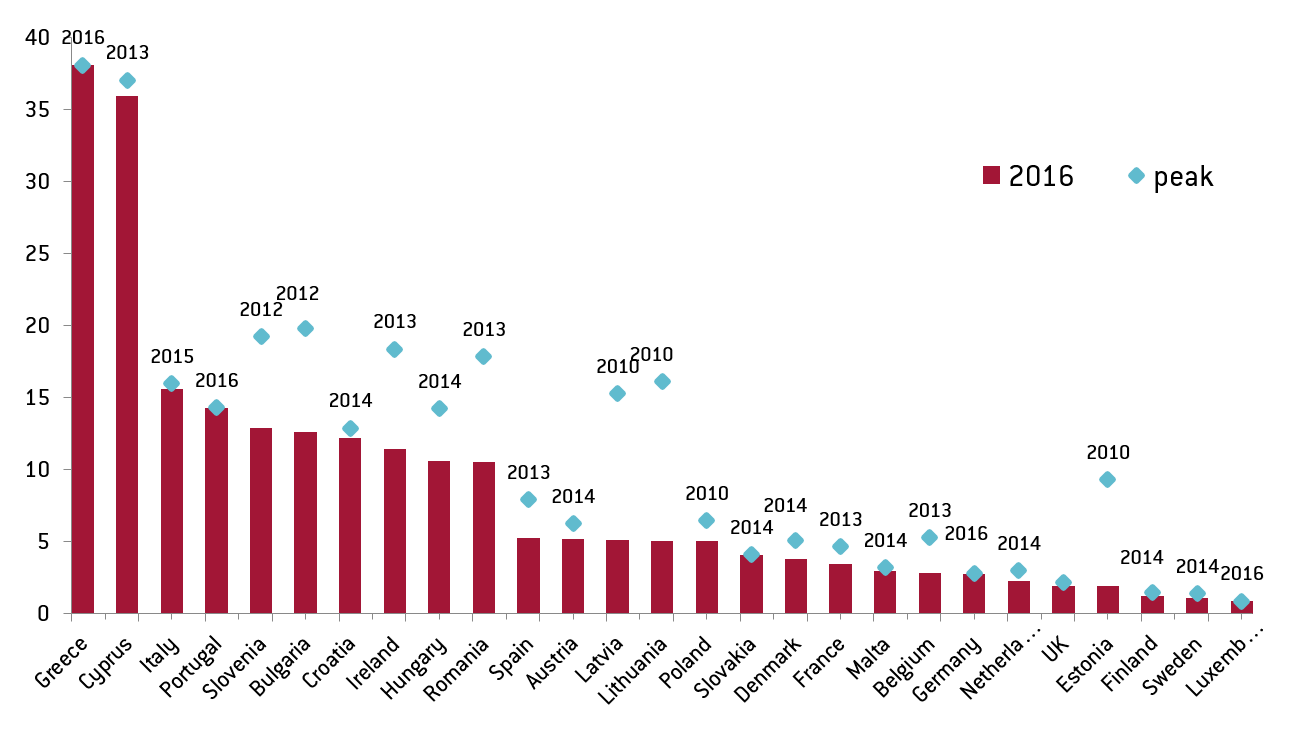

Figure 1: Gross non-performing debt instruments, % of total gross debt instruments

Source: ECB, Note: peak year to 2016Q1

And while a number of countries (namely the Baltics) have managed to decisively resolve bad debts to the benefit of new credit creation, others have made less progress and some have even been unable to make any (Figure 1). The ECB recently issued draft guidelines in an attempt to pool resources and address the issue.

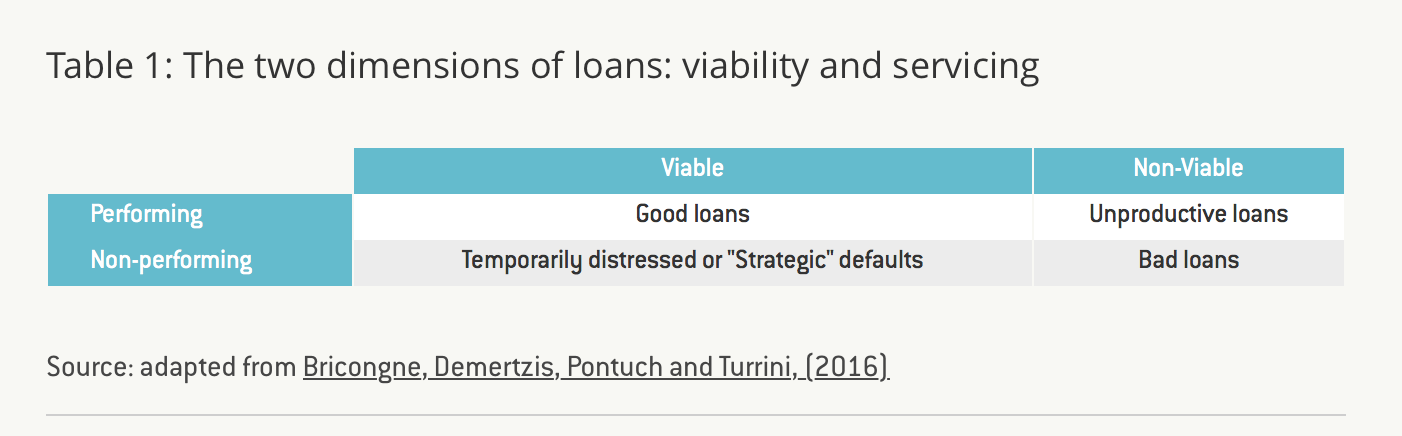

I argue here that an important guiding principle in resolving NPLs should be to ensure that viable debt remains serviced, while non-viable debt gets resolved. But this is not the same as resolving non-performing debt while holding on to performing debt. It helps therefore to categorise loans in two dimensions: viability and ability to service themselves.

Table 1 then provides four possible ways of classifying loans. Performing loans are those that are effectively being serviced and paid back. Viable loans are those for which the underlying assets generate sufficient value to cover funding costs.

Good loans are then, productive loans that are being serviced. This is the only category where debt has a productive role.

Bad loans by contrast are those that do not perform, but also those for which the activities they had financed do not generate enough value. Aiming to resolve these loans in a swift and timely way should be encouraged, as the only way of identifying losses and reducing uncertainty for creditors but also releasing debtors from unproductive activities (second chance).

Unproductive loans are then those which may actually perform in the sense of servicing payments, but do not themselves generate value. Collateralised loans can provide indicative examples here.

Consider a household in the following situation: the value of its house is smaller than the loan that financed it (negative equity); it is liable by law for that remaining difference, as is the case in European countries (full recourse), and has very little possibility of walking away from such obligation by declaring bankruptcy (say through strict insolvency rules). If the household chooses (or needs) to sell that house, additional resources would be needed to repay the loan in full. Also, since the possibility of walking away from such a liability is effectively not available, the household is left locked into servicing a loan which is economically unattractive, as it is larger than the value of the house.

Protecting creditor rights is of course an important reason why insisting on servicing such debt may be a good idea. But when housing markets have gone through sharp corrections, followed typically by a downturn in the business cycle, such arguably unproductive loans may not be isolated cases, but rather wider spread. From a macroeconomic perspective, one ought to therefore at least consider whether the benefits of “creative destruction” outweigh the costs of violating creditors’ rights. The European Commission alludes to this in its last country report for the Netherlands.

Finally, there is also a category of temporarily distressed loans or strategic defaults. This includes either debts that are temporarily in distress but could return to being performing or loans that are non-performing by choice. The latter are the result of moral hazard where debtors choose not to pay back debt even when economically feasible. Evidence shows that strategic defaults increase as negative equity on mortgages increases, and especially when there is no full recourse. However, households’ likelihood to default strategically is shown to be also associated with perceptions of fairness, but also decreasing with the perceived risk of negative consequences of doing so (stigma, negative credit ratings etc). In this respect, indiscriminate protection of debtors or the less than perfect ability to collect collateral may lead to more strategic defaults.

Resolute action to remove non-performing loans from banks’ balance sheets should address both the supply and demand side of credit. Removing bad loans from bank’s balance sheet is important for their health and financial stability more generally. But removing them also from the debtors’ balance sheet is equally necessary if new credit is to be demanded.

Given the four categories presented above, understanding debtors’ true ability to pay back debts and restructure appropriately is crucial in this process. But aligning incentives between the different parties involved, creditors, debtors and relevant institutions (supervisors, regulators but also tax authorities and courts) is equally important.

The aim is to have as much debt fall in the “good” category. If loans are only temporarily distressed, they need to be identified as such and assisted in becoming productive again. Banks should be incentivized to deal with this in a timely manner.

Unproductive loans could be reduced if, for example, the possibility of walking away from debts through bankruptcy was not protracted and/or unforgiving. But here, while banks do not have an immediate incentive to either identify or deal with such loans, macroeconomic policy makers do, in particular when their size is systemic to the economy. Data on debtors failing to make other payments, like taxes or health insurance contributions, could serve as important indicators of financial distress. Such loans should then be assisted in becoming “bad”, which in turn should be treated swiftly to help redirect resources to productive activities. Enforcement and the rule of law are important in identifying “non-performance”; aligned incentives and bank involvement are important in determining “viability”.

What debt? Since the liabilities of the banks toward the general population are largely a sham* then who says the liabilities of the population toward the banking cartel are legitimate?

If banks are a recurrent source of trouble, is it not possible that sham accounting is the cause?

A Postal Saving Service or equivalent is not just something for the unbanked; it is a vital component of an honest money and credit system while government insurance of privately created liabilities is, on its face, corrupt.

*This will be 100% evident if physical fiat is abolished since then it will be impossible to cash a check even though the check says, for example, “Pay to the order of _____” “____________dollars”.

Good loans are then, productive loans that are being serviced. This is the only category where debt has a productive role. Maria Demertzis

Good for whom? Good for workers who may be disemployed (e.g. via automation) with what is, in essence, their own (as part of the public) credit?

ISTM the author thinks that if there are too many bad loans in society then people who might be able to service their debt have less incentive to do so because there is less social stigma when most everyone is wallowing in debt, and her solution to that is get rid of the worst one’s so people keep paying, a base recognition that too much was lent but excusing the perps and saying only the marks who can be productive should keep paying. This solves absolutely nothing. the problem is the creation of unsustainable debt by people who think that in spite of the fact of the unsustainable system, the debts must be paid to keep it going when in fact the creators of the debt should collapse from their ill conceived business models. We would not be in this ridiculous election had that happened. She has no problem with the system, just wants to be able to prune the dead wood, which just happens to be people. the system isn’t going to fix itself, and nibbling around the edges is certain to fail.

Financial companies lend at interest to, well uh um…..insure against the risk of a pool of loans going bad?

Financial companies ‘created’ innovative products (makes me choke on the absurdity of all 3 words….create,innovative,products) for us smurfs to play with.

Financial companies blew up the housing bubble with intent and too the extent that their bought and paid for manipulation of risk backfired (they had intent and purpose to screw the global economy….IBGYBG).

These same private corporations, through their own manipulations crashed the system through fraud and misrepresentations, and mis-warranties…they then got public assistance to get bailed out.

Financialization is all about getting paid a public guaranteed profit and gouge via the bought and paid for government. Look at the oh so legal boosting of med prices and the feigned outrage on the Hill…..most that extra cash comes from gov support…….guess the fake outrage is somebody getting to much public exposure to the pig fest that those with fake outrage are trying to hide…..either that or they are trying to hide the abuse of office by defacing on their sworn duty to act in the public interest.

Ah, remedies, ruleoflaw, incentives, all that stuff, to push as much debt as possible into the “good” category. Does that include Wells Fargo and the rest of debt inviters and inducers and control fraudsters?

Categorize away, O ye very smart economists, invent your incentives, get us to another round of bubbles and Groaf — did I read that “US consumers” having worked through some old debt are now once again maxed out trying to survive and also to live the advertised lifestyle? All this wise churning, just so more debt can be picked up by debtors, and banks incentivized to clean up their balance sheets. Zombie debtors BAD, zombie spin-off banks GOOD?

Query: does nuclear war or total cyber war or just a tech meltdown effectively operate as a Jubilee/bankruptcy? And wil the banister mentality dominate in any next round of humans, too? Reparations! Reconstruction of records of debt, proof of payoff of notes handily lost? Even more unidirectional ruleoflaw?

Does the writer go to church and pray, “give this day our daily graphs, and forgive us our debts as we forgive our good debtors”?

What G_D does the economist pray to?

Excellent–succinct, clear and practical. It sets out clearly the need to balance moral hazard and macroeconomic circumstances. Thank you, Maria Demertzis!

So far governments seem to be ignoring macroeconomic circumstances. Also, they seem to focus wrongly on consumer moral hazard while ignoring the more significant moral hazard at the private banking, central banking, and regulatory levels–particularly the executives.

They say that debts must be repaid. Rubbish.

The heart and soul of capitalism is that bad investments must lose money.

If banks did not get bailed out for making bad investments, if people could walk away from mortgages made during property bubbles, if loans made to corrupt governments could be declared odious and wiped out, then banks would have an incentive to not make such loans.

In the US we have a bubble in student debt for degrees of dubious value at inflated prices. The ‘private’ investors are guaranteed their profits no matter what. If there were no such guarantee, then maybe the lenders would scrutinize the value of said degrees, and colleges would not have been inflating their costs so fast etc.

Thank you. This article is a joke, with a punchline based on long-past notions about “solvency” and “capitalism”. What we have instead today is crony hyper-socialism for debt issuers.

Hedge fundsCentral banks emit their gaseous and aqueous “credit” in unlimited quantities, which we are then supposed to agree to exchange for real goods and services. With every conceivable source of future productivity and demand already claimed this so-called “money” now even has a time preference of less than zero (NIRP). Anyone who cannot see this for exactly what it is should just go down to the parade and marvel at the emperor’s sartorial glory.TG: Well said. This is it in a nutshell.

Nothing new here for us. These methods can work somewhat, but only if they are implemented aggressively and in a timely manner. We did some of this stuff so sloppy it made a bad situation worse. Europe, on the other hand, is paralyzed and desperate for new techniques. Nothing will improve in a capitalist economy, or any economy for that matter, unless it is an expanding economy because everything is still geared to making profits through insane levels of productivity. So what we are doing (nothing) is almost a eulogy. It’s over. We need to shift our urge for progress to a different track. Use sovereign credit without debt to build the world we need and want and create economies that do not require voracious consumption of money and profits.

Appreciated the author’s differentiation of loans for productive purposes vs. nonproductive purposes. Would loans for speculating in the financial markets or flipping houses, corporate stock buybacks, private equity LBO’s, corporate mergers and acquisitions, etc. be considered “productive purposes”?… Seems to me we should as a matter of public policy provide incentives for banks to make productive loans and disincentives for those in the latter category.

Further, while a conceptual framework for debt writedowns is a prerequisite to determine the amounts of losses on bad loans that should be recognized by creditors in their accounting treatment; policies to address the suppression of aggregate demand due simply to the enormous overhang of existing private sector debt and the amounts required to meet debt payments on that preexisting debt are needed. They are two separate issues.

Seems to me we should as a matter of public policy provide incentives for banks to make productive loans

Such as developing and deploying automation to disemploy people? Those may be productive but are they just?

Who writes off the bad debt? Banks? They scammed the politicians and public in 2008 into transferring their bad private debt onto sovereign states and went back to making more bad bets. The only entity that I know of that can write down bad debt is the government once it nationalizes the banks and reopens strong regulated ones with the remaining preforming loans. For the last eight years; instead, there has been quantitative easing, trade treaties that privatize government and right wing politics to flush it down the drain. The next depression is fated to be much worse because the financial nationalization must be performed by weaken, incompetent and ideology riven governments, or nothing is done at all.