By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants

Uber released its S-1, its IPO filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, on April 11th.[1] Press reports indicate Uber is seeking to raise $10 billion and achieve a valuation close to $100 billion. To succeed, investors will need to believe that despite losing roughly $14 billion in the last four years, Uber not only warrants a current valuation that would make it the second most valuable startup IPO in US history (after Facebook) and the second most valuable publicly traded transportation company in the world (after Union Pacific), but that its stock will continue to steadily appreciate once it becomes publicly traded.

Uber’s biggest IPO challenges are to convince potential investors that it has already made substantial progress towards reversing its recent massive losses, and that its businesses have the ability to generate strong, sustainable profits.

Uber’s S-1 not only fails to present any credible evidence about future potential profits, but its presentation of historical results is designed to mislead potential investors about recent improvements that did not actually occur.

Nobody believes Uber’s claim that it earned a billion dollar profit in 2018

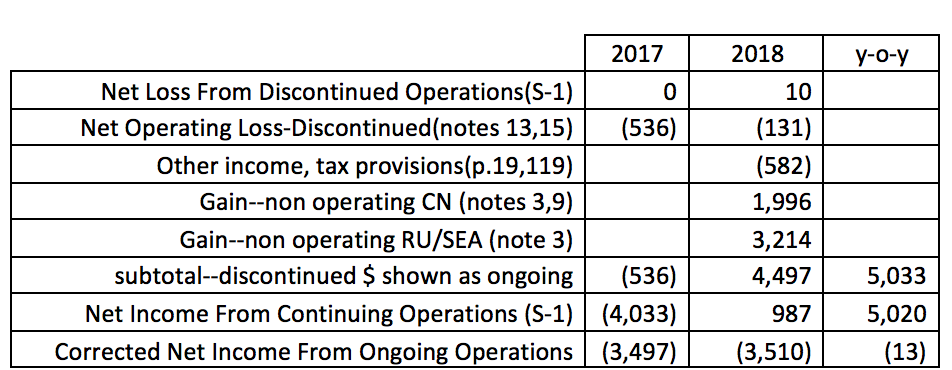

Uber’s S-1 claims that it achieved a $5 billion profit improvement in 2018, moving from a $4.03 billion loss in 2017 to a $997 profit in 2018. Uber’s efforts to manufacture artificial accounting profits that gullible outsiders might not immediately see through first surfaced with the release of its first quarter 2018 results, when a claimed $3003m gain from the sale of its failed Southeast Asia operations to Grab converted a huge loss into a small profit. A fair number of the reporters actively following Uber saw through the original first quarter ambit [2] and the vast majority of reporters following the S-1 ignored the reported $5 billion improvement.

Many current reports have still misreported the 2018 profitability of Uber’s ongoing operations in ways that incorrectly showed meaningful year-over-year profit improvement [3] because Uber was deliberately making it difficult for outsiders to understand those numbers. But most realized that any reported profitability numbers needed to exclude items such as the Grab gain.

All previously released Uber P&L data were based on actual worldwide operations.[4] Uber decided to recast all of its S-1 financial reporting to segregate results from countries (China, Russia, Southeast Asia) where it failed dismally and sold its remaining operations to the dominant local company. This would be reasonable if done transparently and consistently, as it might help potential IPO investors better understand the past performance and future profit potential of the parts of the business that haven’t failed.

If Uber’s intention were to help these investors, the S-1 would have included clear warnings that the 2018 “improvements” were the result of the decisions to abandon these failed markets. Uber didn’t do that, because they are trying to give outsiders the impression that profitability is on a strong upward trajectory.

Uber overstated its 2018 profit improvement of its ongoing operations by $5 billion; ongoing operations lost the same $3.5 billion that they had in 2017.

Uber’s S-1 P&L says that “Net Income From Continuing Operations” improved by roughly $5 billion, from a $4 billion loss in 2017 to a $987 profit in 2018. This is not true; the actual net income from continuing operations in 2018 was negative $3.5 billion, virtually the same as 2017’s result. Uber mischaracterized $5 billion in gains from discontinued operations as gains from continuing operations in order to mislead IPO investors into thinking that the performance of its ongoing business was rapidly improving.

When Uber abandoned its failed Chinese, Russian and Southeast Asian operations, the dominant local companies gave Uber equity and debt instruments to partially compensate it for providing them an easier path to market dominance. These non-tradeable instruments only exist because of Uber’s decision to discontinue operations, but Uber includes their $5 billion value in “Net Income From Continuing Operations”

The current accounting value of these assets is based entirely on Uber’s judgement as to what paper issued by companies currently losing massive amounts of money might be worth someday. [5] If one takes Uber’s judgements at face value, one could conclude that Uber’s only profitable activity is getting paid off for discontinuing staggering unprofitable markets.

In addition to misleading investors about the proper distinction between the results of discontinued and ongoing operations, Uber inappropriately combines the hypothetical future value of non-tradable paper on the “Other Income” line with items that legitimately reflect current year business activity such as interest income and foreign exchange impacts. Uber undoubtedly needed to assign and record a value for these assets somewhere on its financial statements. The problem is Uber’s failure to sufficiently highlight the problematic nature of the assigned values and to ensure investors clearly understood that they had nothing to do with the performance of its current marketplace activities.

The table below summarizes the differences between the 2018 Net Income for discontinued and ongoing operations shown on Uber’s S-1 P&L statement (roughly zero and positive $987 million) and the actual numbers based on other data reported in the S-1. The $5 billion year-over-year profit improvement misstatement results from understating 2017 ongoing profitability by roughly $500 million (because losses from discontinued Russian/Southeast Asian operations had been included with other ongoing operating results) and overstating 2018 by $4.5 billion. Uber’s desire to mislead investors about the actual split (and its failure to improve the profitability of its ongoing operations in 2018) is further illustrated by the fact the numbers for discontinued operations were spread across six different subtables and footnotes. [6]

Uber’s S-1 provides no evidence that its international operations are anything other than financially disastrous

One of the major risk factors identified in the S-1 is that “Our business is substantially dependent on operations outside the United States, including those in markets in which we have limited experience” with 74% of total trip volume currently coming from outside North America. Footnote 2 notes that only 54% of Uber’s revenue comes from outside North America, suggesting that foreign market and competitive conditions substantially reduce average revenue per trip.

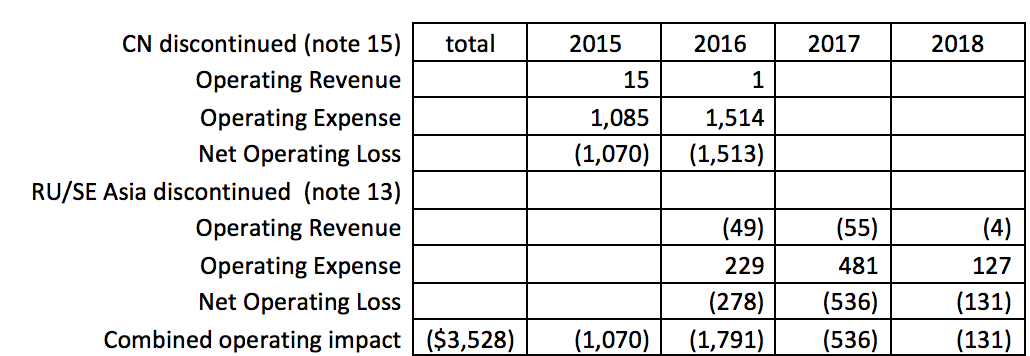

Uber’s S-1 claims operating losses of over $3.5 billion from two and a half years of operations in China and two and a half years of operations in Russia and Southeast Asia. Unbelievably, the S-1 claims the discontinued operations incurred significant expense but had almost no revenue. Footnote 15 explicitly says Uber’s had over $1.5 billion in operating expenses in China in 2016 but only $1 million (with an m) in operating revenue. 2016-18 operating results from Russia and Southeast Asia shown in Footnote 18 are similarly anomalous. Uber’s accountants apparently saw no need to explain why Uber was conducting a large scale business that had no revenue, but the reported data contributes to the appearance of large subsequent profit improvements.

The combination of these data points should serve as flashing neon warning lights to investors trying to understand Uber’s future growth and profit potential.

But Uber doesn’t present any evidence in the S-1 that would mitigate concerns about the international operations it hasn’t yet abandoned. These three markets might have been Uber’s worst, or they might be the only markets where a larger operator was willing to offer Uber a deal including non-tradable paper allowing face-saving claims of hypothetical future gains if they abandoned the market.

Unsubstantiated press reports suggest certain markets (such as India) are especially problematic, and that meaningful competition precludes the possibility of profitability anywhere. Most foreign markets enforce regulatory and safety requirements that Uber freely flouted or nullified in the US.

A further hint that a lot of Uber markets may have especially weak financials is the disclosure that 24% of all Uber trips occur in just five especially dense and wealthy cities (Los Angeles, New York San Francisco, London, Sao Paulo). There is no way to access whether certain type of markets offer Uber the path to profitability that it has clearly been unable to find broadly. Uber’s failure to provide any objective data about profitability by market suggests that it may not have any data that could address these concerns.

Uber’s S-1 does not provide any information that would help investors understand driver economics, or the relative profit performance of Uber’s different ongoing businesses.

All of the Uber economic and financial analysis presented in this series since 2016 has been based on published taxi industry data and the limited Uber P&L data released to the press. Usually the publication of a 300 page IPO prospectus would give outsiders a trove of new data permitting much more detailed and sophisticated analysis of the company’s economics.

That is not the case here. Uber’s S-1 data does not allow outsiders to evaluate the current profitability or the profit trends of any of Uber’s lines of business (car service, food delivery, scooters, etc.). It does not allow outsiders to evaluate whether observed revenue changes are due to pricing or demand or competitive changes, or to understand whether pricing or other marketing changes increased or decreased operating losses. As already noted, outsiders have no way of knowing whether there are significant differences in revenue per trip or profitability by country or by markets within countries, and no way of evaluating what factors might drive those differences.

Uber’s business model depends on a massive number of allegedly “independent” drivers. Uber’s S-1 provides no information (such as base and incentive earnings, turnover, driving patterns, utilization rates, costs of acquiring new drivers) relevant to whether they can continue to provide the capacity that Uber’s customers are paying for. Prospectus readers have no idea whether how driver take-home pay compares to minimum wage levels or alternative low wage jobs, or how much driver compensation has declined. Prospectus readers can’t tell how Uber changed base and incentive compensation in response to marketplace challenges (such as the terrible publicity Uber received in 2017, or local market share battles) or whether Uber has any potential to reduce the driver share of passenger fares going forward. Prospectus readers have no idea what portion of drivers work very long hours, what portion only work during demand peaks and what portion only work occasionally, and have no idea whether these driver patterns align with demand patterns.

Lyft’s IPO prospectus presented ridesharing unit revenue data but Uber did not. Uber only presented the sum of car service and food delivery trips, so prospectus readers couldn’t figure out what customers were paying for the two services separately, or how prices for the two services have changed. The combined data suggest that both growth rates and pricing was declining in the second half of 2018, but prospectus readers have no way to identify the underlying problems, or whether those problem are likely to get worse.

Uber’s S-1 provides absolutely no data on operational efficiency. Its claims about synergies and scale/network effects are completely unsubstantiated. It says, “Our strategy is to create the largest network in each market so that we can have the greatest liquidity network effect, which we believe leads to a margin advantage” and that synergies “across our platform offerings …effectively lower our costs and allow us to invest in a scalable way that becomes increasingly efficient as we grow with each new product or offering.” But Uber fails to provide any supporting evidence about productivity gains or actual margin improvements.

The S-1 highlights the importance of “technologies” that allow better matching of supply and demand and more optimal pricing. But it makes no effort to demonstrate whether these technologies are any better than tools used by other companies and presents no evidence showing that the alleged better matching of supply and demand actually reduced unit costs or how its sophisticated pricing systems actually increased unit revenues. Although Uber’s entire legal defense of its “independent contracting” model is that it is a software company and not a transportation provider, the prospectus does not even pretend that it is a software company.

Uber claims it benefits from significant scale economies saying “we believe that the operator with the larger network will have a higher margin than the operator with the smaller network” but presents no evidence showing that size is the primary driver of profitability. In reality, other factors such as the ability to maximize the revenue utilization of assets and labor against complex demand patterns are far more important drivers of transport profitability. Since Uber is already orders of magnitude larger than any previous urban car service operator, if size was the critical driver one would think these powerful margin effects would have shown up by now.

Uber’s claims of powerful network effects are nothing more than the assertion that some drivers can carry both passengers and food deliveries and that “Uber Eats is used by many of the same consumers who use our Ridesharing products.” Uber has no evidence that its platform increases the loyalty of either drivers or customers. The most likely explanation for the rapid recent growth of Uber Eats is not that customers are locked in to an app they like, but that customers got the same massive subsidies that drove the early growth of Uber’s car service. Airline passengers also buy hotel rooms and rental cars and restaurant meals But airlines understand that the synergies of combining these products within a single smartphone app owned by a single corporate entity are trivial.

Uber has internal data that could address all of these efficiency, pricing and margin questions in great detail. One can reasonably presume that they chose not to include any of it in the IPO prospectus because it would raise serious doubts about the company’s future growth and profit potential.

Since the prospectus fails to make a legitimate, compelling case for strong near-term profit improvements, its other shortcomings can be ignored.

Numerous other sections of the prospectus fall somewhere on the scale between “should raise red flags” (Uber has over $1 billion in San Francisco real estate commitments) and “argument too ludicrous to take seriously” (Uber’s true growth potential is defined by the worldwide market for urban travel). Again the question is not whether Uber might someday reach breakeven, but whether investors see enough robust long-run revenue, profit and equity growth to justify making Uber the second biggest startup IPO in US history and the second most valuable publicly traded transportation company in the world.

Uber correctly notes that all of its expansion opportunities involve industries with much more challenging economics and much more efficient incumbents than ridesharing. The IPO is clearly dependent on investors who think that years of powerful revenue growth can drive equity values even without profits, and the prospectus strongly emphasizes that Uber has yet to achieve a 1% share of its near-term market potential. But Uber fails to tell investors how much capital will be required to fuel this long-term growth (it already has $7.5 billion in debt), or how long it will take to earn returns on that capital.

Uber notes that it has already invested $475 million in autonomous car development, but doesn’t say how much more investment will be required, how its approach offers greater promise than what its competitors are doing, how long it will take before it believes autonomous cars can begin to produce meaningful revenue, and makes no effort to explain why Uber’s investments are likely to succeed given the huge technological, legal and competitive obstacles. There are various unsubstantiated claims about “synergies” between scooters and taxis, but absolutely no explanation of the current economics of scooters or how they might someday become a profitable business. The prospectus briefly mentions Uber’s investment in flying cars, but seems to be hoping nobody notices.

Growth beyond Uber’s core taxi business requires being able to profitably produce services substantially cheaper and more convenient that existing options such as private car ownership and public transit. Since Uber is still billions away from being able to produce profitable taxi service, there is little need to spend time evaluating Uber’s long-term growth claims.

__________

[1] The Uber S-1 can be downloaded at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1543151/000119312519103850/d647752ds1.htm

[2] Can Uber Ever Deliver Part Fifteen–Uber’s Q1 Results – Reporters Show They Aren’t Up to Reading Financials (May 24th, 2018)

[3] Most news reports, including the New York Times, Washington Post, CNN and Fox Business have reported a headline $1.8 billion loss. This is a non-GAAP EBITDA contribution measure, not a GAAP profit measure. A couple others reported Uber’s $3.0 billion loss from operations, which is also not a true profit measure.

[4] Uber financial results through mid-2017 are documented in Hubert Horan, Will the Growth of Uber Increase Economic Welfare? 44 Transp. L.J., 33-105 (2017). Available for download at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2933177. Subsequent P&L data can be found in other parts of this series including Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Thirteen: Even After 4Q Cost Cuts, Uber Lost $4.5 Billion in 2017 (18 Feb 2018) and Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Seventeen: Uber’s 2018 Results Still Show Huge Losses and Slowing Growth as IPO Approaches (16 Feb 2019)

[5] The S-1 notes that neither the 2016 Didi transaction nor the 2018 Grab transaction have been approved by the local competition authorities. Rulings that these deals unacceptably exploited the elimination of competition would presumably reduce these hypothetical paper values to zero.

[6} There are several discrepancies in the data Uber reports. Footnote 3 says the gain from the Yandex transaction $1234m; footnote 9 which says the value was $954m. The $2328m Grab number in the S-1 is inconsistent with all previous releases of 2018 Uber P&L data which said the Grab value was $3003m. Presumably Uber’s accountants could explain these discrepancies, but they demonstrate that those accountants were going to great lengths to make it difficult for S-1 readers to figure out the actual financial split between discontinued and ongoing operations.

Quoting from the post:

Although Uber’s entire legal defense of its “independent contracting” model is that it is a software company and not a transportation provider, the prospectus does not even pretend that it is a software company.

To which I say:

This is a big, waving red flag (or target) to all who are involved in employment litigation with Uber.

How is this kind of prospectus even legal?

If it wasn’t for the real threat of pension funds and state-owned investors would chip in, as well as all small-trade suckers getting fooled in post-IPO price-drops, I would have laughed my head off thinking predators predating on predators or neoliberals fooling neoliberals.

Glad to see the SEC is doing their job of making sure unscrupulous corporations don’t mislead investors [/sarc]

If I was a cynical person, I would note that as this company has never made a profit, has indulged in fraud to boost its earnings, and may never ever turn a profit, that something else may be going on. Uber itself has said “We expect our operating expenses to increase significantly in the foreseeable future, and we may not achieve profitability” which is not exactly a confidence-booster. It may be that the smart money has their cash tied up in Uber and needs to unload it to make a profit. That they are looking for stupid money to pile in when Uber goes public and dump their holdings on them. After all, it’s not a profit until it goes into the bank. But that would be if I was a cynic.

Uber IPO = Big short fot the Smart Money?

Look at Lyft. As soon as options began trading all hell broke loose to the down side.

Traded down to $55.55 today from $88.60 opening day high.

Ouch. Down 37% in less than a month.

Reading this article, something about the Greater Fool comes to mind…

Any entity, fund, or person investing in Uber for the long term has to be willing to do whatever it takes for Uber to have a transportation monopoly.

It just remains to be seen how many of them there are vs investors at the top of the pyramid willing to say anything to cash out big now.

How can the SEC let an IPO go forward with such misleading data? Neoliberal Scams correctly points out that people’s retirement funds could be invested in this.

WTF SEC ?

Wait, what? Dara Khosrowshahi is a good guy!

Adding, thank you for this mind-bending post. To be fair, Khosrowshahi doesn’t think small.

Well if nothing else, the S1 proves he knows exactly what he is doing. He is a Colin Powell rent-a-reputation type.

One thing that I wonder about whenever I hear that autonomous vehicles will save Uber/Lyft/etc…

Who will own the damned things? Since there’s no driver, presumably they’re now on Uber’s balance sheet. Or, since Uber “may never make a profit”, an enormous leasing company, as in the airline industry. But how do you set operating lease rates on autonomous cars with no pricing track record, so that the leases aren’t recast as capital leases? How do you set insurance rates? Who provides the capital? A whole ‘nother level of uncertainty. And the lenders to leasing companies aren’t exactly the kinds of suckers who would buy Uber in an IPO.

Of course not; Uber will generously allow you, the plebes, to convert your car to fully autonumous – on your dime, of course (perhaps using a “Uber Convert X” program where you just need to sign on the dotted line for them to finance the conversion) and then graciously allow you to Make Money While You Sleep (and take all the risk, including any related to injuries etc).

Uber gets paid, gives you a pittance that covers fuel and washing the car (but certainly not long-term maintenance) and everyone who matters profits! It’s win-win-win, and you’re the mark, not one of the players.

This is exactly what I’ve been wondering for a couple of years. Under the current system, the drivers provide the cars, pay the insurance, buy the gas, pay for repairs, replace tires, and pay for a host of other minor expenses. We don’t yet know how much self-driving cars will cost compared to ordinary cars, but can be pretty sure they will cost a lot more. Then you have the expenses currently borne by the driver-owners being taken up by Uber. I don’t see how the economics are supposed to work. I’ve never actually gone looking to see if anybody asked Kalacki or if Uber has explained this. It just seems like they’re salivating at the prospect of sticking it to workers.

After 5 years as a full time Ride SERVICE! driver (as im not “SHARING” sh@# w anyone). It baffles me how many customers are so clueless about what these companies have really been up to.

When Uber comes up in conversation, and I mention that it has burned billions and never produced a meaningful profit, people often don’t believe it.

I would be interested to read about your experiences as a driver.

People need to be told they’ve never paid the real rates, and Uber kept subsidizing their rides by big margins only to gain market share (and show investors the business potential) as opposed to make profits.

I’m assuming any comeuppance or reckoning for Uber would probably be banal and mixed, not like a thunderclap. Once the IPO happens, let’s say they’re having a mediocre time the way Lyft is and trading for less than the IPO price. Yet they’re shielded from just folding, because of ongoing money from institutional investors? Is it accurate to say that index funds buy one of everything, giving every company on the exchange ongoing funding no matter how ludicrous they are?

For a while there were reports about Twitter not doing well. But Twitter never actually folds. Top management can be sacked and replaced, like with Dorsey. Snapchat doesn’t fold.

Homejoy, on the other hand, did simply fold, over misclassification suits. The private companies in CB Insights’ series of post-mortem reports sometimes just fold, and the founders write tearful final blog posts about how “we failed to scale blah blah,” or whatever.

What can it mean in practical terms to be “heading for a crash” once you have public status washing out the severity of particular bad acts or lousy 10-Q’s ? I guess the public-company version of going kaput is to be sold off to PE?

Thank you for the great analysis, Hubert.

Note: the graf beginning “All previously released” has a problem. I think two versions of a sentence got in.

Thanks for the catch. Don’t ask how I read the post and managed to miss that. Fixed.

Thanks for the quick (and devastating) analysis.

That such a blatant fraud is almost certainly going to be allowed to proceed to a public share offer is yet another sad indictment of the regulators. There’s going to be a lot of losses when all this crap unwinds.

Holy crap. Am I reading that right? Uber booked $5 billion of one time gains as regular income in order to juice its net income above the profit line, just in time for the IPO? So it’s pretty much just a massive pump and dump? Assuming this is all GAAP, I have to wonder whether whether accountants could bear any kind of liability for this transparent attempt to mislead.

I was trying to boil the Uber debunking down into a few sentences recently and came up with this rationale:

1. When considered as a collective business across the Uber platform and independent drivers (which is the right way to do it for competitive analysis purposes) Uber has no real cost advantage compared to traditional taxi services, and in fact has some disadvantages.

2. This means that for Uber to be profitable, it needs to either extract a disproportionate share of the profits relative to its drivers (i.e., treat them as a cost sink) or add enough value over and above traditional services that people would be willing to pay a premium for it, most likely both. Its branding also supports this, by touting all the ways in which it’s superior to taxis.

3. However, it is instead selling its services at a substantial discount (and below cost) thanks to massive subsidies from investors.

4. As a consequence of #3 we still have no idea whether #2 would be a successful long term business model for Uber, since they have never tried to sell that way.

On point #4 we can maybe get a rough idea by polling people who use Uber and asking whether they would still use it if it was, say, 20% more expensive than traditional taxi services. Unless we get a clear yes across the board on that question, Uber is never likely to show a profit.

An alternate strategy would be for Uber to use its ride business as a loss leader to gain a leading position in future market areas and ultimately earn enough money from those to justify the losses to date. Uber is attempting to do just this in multiple areas (food delivery, self driving and/or flying cars…) Some of these may ultimately turn out to be impossible. Others may be possible as a niche service for the wealthy but impossible as a mass market service at prices most people will be willing to pay. Even for the subset that might one day become a profitable market at a large scale, there is generally little reason to believe that Uber will be the market leader.

Uber and Lyft will never make money given the current rate structure. (even if Level 5 autonomous cars debuted tomorrow)

—-unless base rates rise dramatically (but crushing demand) and city governments hand over lots of public curb space for cars to park between rides. (think taxi stands galore to cut down on dead-heading, possible given the willingness of most local governments to do whatever a lobbyists says)

Care of Lambert Strether ‘Water Cooler’

‘A lot has been said about the Uber IPO but maybe none as cogent as this FT comment’

I like it!

https://twitter.com/bytebot/status/1117323665865969664/photo/1

Nailed it!

Hubert-

Are you aware that Chicago just released a treasure trove of data on uber/lyft rides in the city? Pretty detailed data similar to what taxis are required to release. I know in the past you’ve mentioned that it’s tough to evaluate Uber & lyft’s claims because they don’t release data, so I’m curious whether there’s any insight to be gained from the city’s data release.

@hubert- what about grab? Here in Singapore they seem to have taken over the taxi industry. Are they different in any meaningful way or do they make the same amount of huge losses and are playing a monopoly game?

Everything that is applicable to Uber, also applies to Grab (which ‘took over’ Uber’s SE Asia operations). Grab is not profitable either .. and also doing the same nonsense like Uber (expanding into food delivery etc). Lots of drivers that used to be Grab drivers have now moved back to being plain old Cab drivers, at least those who can figure out the maths – for those who have the much harder to obtain taxi vocational license.

The private hire / Grab-applicable license is much easier to obtain as they convinced the regulators that no regulations need apply until all the conditions are fully firmed up, since they are a tech disruptor… I’m serious, that was the gist of their pitch which worked.

The long con is drawing to an end.

How can people be so gullible?

The SEC surely must put a halt to this now.

Will banksters /fund mgrs helping their high net worth VC friends get out by simply plonking retirees funds into this mess? Surely there must be laws relating to fiduciary duty?

1 – amazes me too.

2 – yes.

3 – surely you jest

Hahahahaahahahaha! You make the comedy.

Selling a failing operation for overvalued stock and calling that a gain seems like the kind of thing Joe Kennedy put a stop to. When did that become legal again?

I can see a way for Uber to become profitable, eventually. Its a long, crooked road to get there, with potholes everywhere, and it has to do with AVs.

What is the most valuable ‘thing’ regarding AVs? Is it safety, where the digital brains behind the wheel never makes a mistake? Is it conservation of resources, where fewer cars are made because ownership declines and individual transportation is efficiently handled by Uber? No and no. These are a side benefit and rather insignificant.

The most valuable thing regarding AVs is ‘trapped attention’ and here is MIT guy to explain it.

Now, Uber depends on desperate people that failed arithmetic to drive cars, therefore sidestepping the cost of car ownership.

Uber could do something similar with AV cars it owns by using a TV type advertising model and having advertisers absorb some of the cost of owing these AV cars. It could offer quiet rides for the full price with no ads or take the ads and get a deep discount.

Imagine in ten or twenty years down the road, you hop into an Uber AV car and for a cheap ride, all you have to do is watch and listen as peckerhead Bezos implores you to buy moar crapola from Amazon, the only company left selling anything.

Such a deal. How could you say no?

Eh. Perhaps. I think you are underestimating the ability of Uber (or whatever company that comes after them) to bullshit the law, the drivers and defraud the owners of the capital that they use (i.e. the cars).

Why should Uber/Grab/NextGenAICabCompany own any of its cars? That sounds like it requires a lot of capital, not to mention that of course, the owner of a car is far more responsible for any injuries that the car causes than the poor, little tech-disrupting company that just happens to tell the car where to go (if any incidents is not deemed the fault of the people in the car, because reasons and tradition).

Thus, they will allow the current model, where a mark owns the car, but instead of having the mark (or someone, they don’t care) drive it around, the car will be autonomous but not directly under the control of Uber; Uber simply interfacing with the autonomous software, sending it a destination. Thus, with responsibility vaguely diffused between owner of the car, autonomous software company X and the autonomous hardware supplier, Uber will attempt to silently crawl off into the night with the profits.

That’s what I would attempt, were I forced to somehow handle Uber in its current metastasized state.

As I have mentioned before, Uber could have just been an app that earned an “honest” arbitrage between drivers and customers (building on ease of use “sign up once, get driven everywhere!”) and did the occasional funny thing (Uber Helicopter) with, perhaps, a high-end limousine service in areas where that makes sense (if nothing else as a loss-leader to get it out there, as well as having to keep it up since they’ve been doing it since the start). That app could have earned some money (probably quite a bit due to reputation – why go with Country App X when you have Uber installed?), but it could not create a monopoly, which is what they seem to aim for.

Missing quantifier:

“moving from a $4.03 billion loss in 2017 to a $997 profit in 2018” => “moving from a $4.03 billion loss in 2017 to a [$997 million] profit in 2018”

Hubert – can you point me to the place in Uber’s S-1 filing which contains detailed forward looking financial statements? (You say that all IPO document contain those in multiple articles)

Thanks!

Love the series.

Housekeeping: The Uber tag is missing from this post.(