By Martin Ravallion, Director of the Development Research Group, World Bank. Cross posted from VoxEU

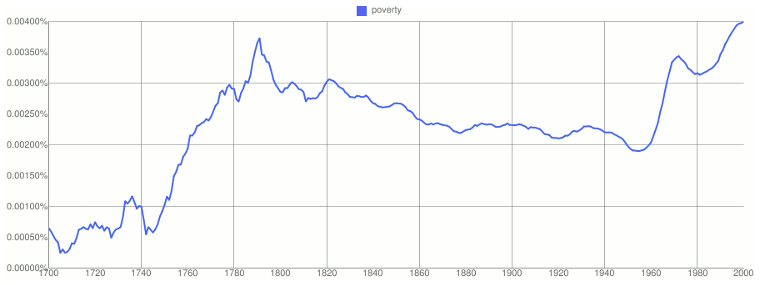

For how long have we cared about poverty? Tracing the number of references to the word “poverty” in books published since 1700, this column shows that there was marked increase between 1740 and 1790, culminating in a “Poverty Enlightenment”. Attention then faded through the 19th and 20th centuries, leaving room for the second Poverty Enlightenment in 1960 – and interest in poverty still rising.

Public awareness of poverty could well be at its historical peak. Figure 1 plots references to the word “poverty” in Google Books from 1700-2000. This is a moving average of the incidence of that word, normalised by the total number of words in the books published that year. We see that there was a seven-fold increase in the incidence of references to poverty between 1740 and 1790. Toward the end of the Enlightenment, around the time of the French and American Revolutions, there was what I will call a “Poverty Enlightenment.” But attention then faded through the 19th and 20th centuries. A significant awakening of attention to poverty – a second Poverty Enlightenment – came around 1960. The peak in the average incidence of references to poverty was around 2000, when the available series ends.

Figure 1. Incidence of references to poverty in Google Books 1700-2000

What lies behind these two Poverty Enlightenments? In a recent paper (Ravallion 2011), I have tried to answer this question by combining the rapid word-counting power of the Google Books Ngram Viewer (the Viewer hereafter) with my (much slower) reading of the historical texts.

The first Poverty Enlightenment

In his excellent history of the idea of distributive justice, Samuel Fleischacker (2004, p.7) argues that in pre-modern times, “the poor appeared to be a particularly vicious class of people, a class of people who deserved nothing”. In the early 18th century, Robert Moss instructed the poor man “to rest contented with that state or condition in which it hath pleased God to rank him”. The French doctor and moralist Philippe Hecquet wrote in 1740 that “The poor are like the shadows in a painting: they provide the necessary contrast”. To the extent that any effort was made to explain poverty it was seen as either “God’s will” or a purely private matter, stemming from bad personal behaviour, such as laziness. Indeed, hunger was often seen as a good thing, as it motivated poor people to work.

A new questioning of longstanding social ranks emerged in the later 18th century, most notably in France. In the 1780s, The Marriage of Figaro, a play by Pierre Baumarchais, had Parisian audiences taking side with the servants in laughing at the aristocracy. Some of this new egalitarian spirit spilled across the English Channel, though it met with some stiff resistance. In 1806 Patrick Colquhoun, the founder of the police force in England, wrote that poverty “is a most necessary and indispensable ingredient in society, without which nations and communities could not exist in a state of civilisation.”

The first Poverty Enlightenment was the time when poverty started to be seen as a politico-economic outcome rather than the manifestation of some natural order. Poor people started to aspire to be otherwise. But poverty was still widely accepted in the literature as a more-or-less inevitable fact of life. The economics of the 18th and 19th centuries did not offer any serious challenge to this view. Some economists saw poverty as an essential condition for economic development. No doubt it was agreed that rising real wage rates would reduce poverty, but it was argued that this would undermine wealth accumulation by reducing labour supply and (in the Mercantilist schema) making exports uncompetitive, and even corrupting the values of workers as they aspired to luxury goods. Thomas Malthus famously saw ecological disaster ahead, with poverty and famine as the only check against rising population. Nor did Adam Smith – far more optimistic than Malthus about the scope for overall social progress – entertain much hope that the fruits of economic development would be equitably distributed; Smith (1776, p.232) wrote that: “Whenever there is great prosperity, there is great inequality. For one very rich man, there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many.”

The second Poverty Enlightenment

If Western Europe in the late 18th century gave birth to the modern idea of distributive justice, based on the notion that a minimum standard of living should be attainable by all members of society, it seems that the idea died a slow death in the public consciousness for the next 170 years. But it stayed alive in scholarly writings. In economics around the turn of the 20th century, Alfred Marshall (1890) was asking in the opening pages of his Principles of Economics, “May we not outgrow the belief that poverty is necessary?” (p.2).

But the re-awakening of popular awareness – the second Poverty Enlightenment – did not arrive until the 1960s, and it was particularly striking in the US. In the wake of the civil rights movement, the rediscovery of poverty in the midst of affluence in mid-20th century America was stimulated by important social commentaries, including John Kenneth Galbraith’s (1958) The Affluent Society and Michael Harrington’s (1962) The Other America (both best sellers at the time). These helped initiate a political response in the US, including new social programs targeting poor families, under the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty.

Galbraith and Harrington wrote their books at the right time to have the influence they had, given the combination of new affluence for the majority and optimism, including about policy, that prevailed in America in the 1950s and 1960s. But as times changed, a backlash emerged. The counter-attack came in the 1980s (as exemplified by Charles Murray’s, 1984, Losing Ground), with welfare reforms following in the 1990s; 30 years after declaring a “War on Poverty,” America declared a “War on Welfare.” There are continuing debates today about poverty, its causes and the appropriate policy responses, throughout the world – echoing many of the debates of 200 years earlier, including on the extent to which poor people themselves are to be blamed for their poverty.

Another factor in the surge of attention to poverty in the late 20th century, was the public’s increasing awareness of the existence of severe and widespread poverty in the developing world, which started to attract global public attention in the 1970s. The World Bank’s (1990) World Development Report: Poverty was influential in development policy circles, and soon after a “world free of poverty” became the Bank’s overarching goal. A large body of empirical, survey-based, research on poverty followed in the 1990s.

Poverty and policies

The last three centuries have seen a shift away from complacent acceptance of poverty, and even contempt for poor people, to the view that society, the economy and government should be judged in part at least by their success in reducing poverty. There are a number of possible explanations for this change. Greater overall affluence in the world has probably made it harder to excuse poverty. Expanding democracy has given new political voice to poor people. And new knowledge about poverty has created the potential for more well-informed action.

The last 300 years have also seen large swings in attitudes toward markets and the state, including on the potential for effective government intervention. The post-WW2 period – the “golden age of government intervention” (Tanzi and Schuknecht 2000) – saw rising attention to a wide range of policies. The counterattack – based in some measure on economic analyses of the limitations of governmental solutions to economic problems, but also driven by an effective political mobilisation – started to gain ground in the late 1970s.

However, while the cycles of debate and reform continue, the written record does not suggest that the end of the golden age of government intervention came with a widespread diminution of interest in poverty. Indeed, the incidence of references to poverty (and inequality) followed a clear upward trend in the latter half of the 20th century and, since 1980, we have seen a steep increase in references to social policies, social protection and civil society organisations (Ravallion 2011) – no doubt (in part at least) as a reaction to rising public concerns about poverty and inequality.

Translating this peak of awareness of poverty at the outset of the 21st century into effective action is, of course, another matter. The second Poverty Enlightenment has entailed much debate and a mixed record of successes and failures in the fight against poverty. But it is at least encouraging that the recent rebirth of the resistance to government intervention that prevailed through most of the 19th century has not come with a return to that century’s complacent acceptance of the inevitability of poverty.

Dont you think that the rise of the labor movement in the 1890s and the Great Depression created an awareness of pover in between those times, not to mention the financial panics of the 1870s and 1890s. This seems like a kennedy-centric view.

Maybe we are talking about elite economist reacting to public pressure to solve poverty and not a lack of awareness. Afterall calls for liberty equality and fraternity address poverty in empowering ways, from the people most effected by poverty, so does the labor movement.

I think the present rise in poverty worldwide is due to population increases in poor countries.

Fix that and the numbers drop.

In western countries it is obviously due to the slowdown.

We’re still waiting on a fix for that.

By now we’ve learned how the economy works, and we know that even to this day there’s no absolute scarcity in anything necessary, but rather that all scarcity and all poverty is artificially, intentionally created by the “elites”. The existence of poverty is a direct measure of their robbery.

Once everyone has access to the land and the freedom to individually or cooperatively cultivate it, only then will we find out who’s truly incapable of working on account of some turpitude. I guarantee that fraction will be negligible.

It should go without saying that any level of poverty, unemployment, street crime, or “idleness” existing within a top-down command economy structure is 100% the creation and responsibility of the elites who impose that structure. If such effects exist to any significant extent amid absolute plenty, on its face that proves the dispensation is a failure and a travesty – morally, rationally, and on a practical level.

The last three centuries have seen a shift away from complacent acceptance of poverty, and even contempt for poor people, to the view that society, the economy and government should be judged in part at least by their success in reducing poverty. There are a number of possible explanations for this change. Greater overall affluence in the world has probably made it harder to excuse poverty. Expanding democracy has given new political voice to poor people. And new knowledge about poverty has created the potential for more well-informed action.

We ought to add to that how clear it’s become that the political and economic elites are absolutely worthless, destructive, and inferior. They’re worthless parasites who shouldn’t even be tolerated as street beggars, let alone allowed to steal all power and wealth.

Do you really consider the likes of Lloyd Blankfein, Dick Fuld, Barack Obama, or George Bush to be even anywhere near your equal, let alone your infinite better?

Very well said, attempter.

We should add too that global GDP has grown approximately four-fold over the last three to four decades, whereas global poverty has doubled (according to the UN). And yet still the ‘experts’ bleat for ‘growth.’

The situation we face as a species demands a totally new way of thinking. This is no longer about ‘earning a living’ or wages for labour, it is not about economic ‘growth’ as the only palliative for all our troubles, forced upon us by the nature of the money system anyway, it is about wising up and recognizing the reality of our predicament as a species. Do we want to survive, or don’t we? All other questions are secondary to that. The multiple crises we face go way beyond nationality, religion and ideology. This is about the knowable facts of homo sapiens sapiens as part of planet earth, as part of nature, of the universe. It is about our ability to destroy and create. How are we to use our accumulated wisdom going forward? Remember, it’s not possible to stay the same.

One more thing: Elitism is obnoxious and always was. It presupposes, by definition, that the vast majority of us are cannon fodder, slaves, wage-slaves, dumb consumers, pick your term. It is responsible for the disgrace that passes itself off as an education; for the rampant corruption and decadence, now in such an advanced state stating the truth is an offense; and for poverty generally, as attempter points out. My contention is that only sociopaths and psychopaths can remotely ‘enjoy’ holding onto enormous power and wealth, the socioeconomic defense of which causes untold misery, death and destruction. Therefore a major requirement for ‘running with big dogs’ is a lack of empathy.

As attempter rightly asks: do you think they are even remotely your equal?

That’s why this question:

Do we want to survive, or don’t we?

has to include, for its correct answer, the realization that we cannot negotiate or compromise with these psychopaths or with any element of their way of thinking.

Funny how only White and Black people stand on our freeway offramps begging. The Central Americans are too busy

standing down the block waiting for day labor work.

How is that the fault of a “top down command structure”?

Because the land they have the right to farm and the materials they have the right to craft and the tools they constructed to use for these things have been criminally enclosed against them. That’s been the work of command policy, every step of the way.

The people want to work, have the right to do so, and are the rightful owners and managers of all they produce. A criminal wall was put up against them. Democracy’s task is to tear down that wall.

Because Obama’s ICE teams will beat and deport anyone who even looks illegal?

Freeing mankind from poverty is a battle which pits man against nature. But it is a battle that has to be fought on two fronts. If mankind is to free itself from poverty, then man must overcome not only physical nature, but human nature as well.

An interesting exercise is to take Ravillon’s graph and indicate upon it the lifespan of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), which coincides with the rise of romanticism, and the lifetime of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968). Perhaps more than any other historical figures of the West, these two had the ability to imagine a fairer and more just world, and the faith and conviction that this world could be realized. According to Ravillon’s graph, awareness of poverty increased greatly during both these men’s lifetimes.

Then one can indicate the American Revolution (1775-1783) and the French Revolution (1789-1799) which came at the crest of what Ravillon called “the first poverty enlightenment.”

Speaking exclusively of the battle against physical nature, one can indicate the two most pivotal events on this front on Ravillon’s graph. The first is the coal revolution which started about 1780. The second is the oil and natural gas revolution, which began in about 1910.

Of course the battle against human nature and the battle against physical nature are hardly independent of each other. They are inextricably intertwined, and what happens on one front affects what happens on the other.

David Sloan Wilson in Darwin’s Cathedral provides the intellectual framework that I believe best explains the events of the last 300 years:

Human societies become structured in many different ways and often become highly stratified. Behind all of them, however, is a strong moral sentiment that society must work for all its members from the highest to the lowest. I interpret this spirit of communitas as the mind of the hunter-gatherer, willing to work for the common good but ever-vigilant against exploitation. In small groups the spirit of communitas results in egalitarian societies with an absence of leaders. In larger groups, which must become differentiated to function adaptively, the spirit of communitas serves as a kind of moral anchor. A large society is robust to the extent that its structure fulfills the spirit of communitas. When it fails, as it so often does from the temptation to benefit oneself at the expense of others within the society, members withdraw their commitment and work to destroy what they previously supported. By a slow and halting process, marked by frequent reversals and by no means destined to move forward, social structures evolve that work roughly for the common good. One important design feature of a robust society is bi-directional control. Leaders and other authorities are required to coordinate action in large society, but they must also be controlled to prevent abuse of their power. According to Boehm (1999), the anthropologist who has been most influential in developing the concept of guarded egalitarianism, even the most powerful chiefs of traditional societies were ultimately accountable to their so-called subjects.

I’ve read Boehm’s “Hierarchy in the Forest” and found it both interesting and deeply flawed. For Boehm egalitarianism is inverse domination, or upside-down hierarchy, with the many dominating the few. Things like teasing and social exclusion are explored as devices for maintaining an egalitarian set up. And yet is it ‘domination’ that is sought via these means? Isn’t it more accurate to say that egalitarianism seeks fairness? It is domination hunter gatherers avoid, they do not seek it out explicitly. Boehm looks from within our culture back at hunter gatherers and simpler settled tribes, and projects too much of his own prejudice on what he finds, despite his quick look at primate hierarchies in the opening chapter, the study of which is controversial at best.

However, more deeply still, we need to ask ourselves what we really mean when we say ‘human nature’ or ‘the battle against nature.’ I don’t want to be the armchair philosopher here, and accept that humanity has, since farming, increasingly perceived itself as separate from, and looking down upon, nature, nature being a pool of resources there for pursuit of more and more comfort. But this perception is in fact false, potent as it is. The social structures, the cultures, the socioeconomic systems that have grown in complexity while humanity has laboured under this false perception have shaped our behaviour more profoundly than genes alone can do. We are now, as we always were, products of the environment. A child raised by wolves away from language and culture for ten years cannot become a functioning member of society thereafter, no matter how healthy her genetic make up, no matter how human. Even upright walking will be beyond her.

The complexity you cite, DownSouth, is also, in part, a consequence of this false perception. The complexity we have built up can be differently set out, perhaps simpler though comfort-oriented, and need not require fixed hierarchy at all. Open Source Software is an example of how self-organization can operate more effectively than imposed hierarchical organization. The Egyptian revolution, “Revolution 2.0”, is another example. Something neutral-ish, call it technology, can allow self-organization/egalitarianism to flourish, where it might otherwise fail in an overly oppressive and rigidly hierarchical setting.

The tension today is predominantly, I feel, a direct result of humanity’s technical ability to organize society very differently, and our dim but growing awareness of this, both clashing with vested interest. Human nature is only relevant in so far as it has been formed by culture and environment these last millennia. Human nature, in terms of our genetics, is not the impediment you seem to imply it is. Not in my opinion anyway. Descartes was wrong.

Also, was there poverty when humans were less separate from nature? During hunter gatherer periods for example? Does fighting poverty pit man against nature, or does pitting man against nature create poverty? I believe the latter is far truer.

So what is “fairness”? Is fairness egalitarianism? Or is fairness a merit system, with some sort of a safety net for those who, for whatever reason, can’t cut the mustard? Do most people want equal outcomes for everyone, regardless of performance, or do they want a merit system?

As to domination, what is it you hope for? Is it a coercion-free society? I don’t believe that exists. As to those who study primitive cultures in the modern world, there’s never been any evidence of a society free of the type of domination you describe. Quite the opposite, here’s what they’ve found, as reported here by Hillard Kaplan and Michael Gurven:

Although certain levels of imbalance [of food sharing] may be due to differential need, there is much evidence to suggest that such imbalances are sometimes tolerated only within limits. Those who do not produce or share enough are often subject to criticism, either directly or through gossip, and social ostracism. Anecdotes of shirkers being excluded from distributions until they either boosted their production or sharing levels are found among the Maimande (Aspelin 1979), Pilaga (Henry 1951:199), Gunwinggu (Altman 1987:147), Washo (Price 1975:16), Machiguenga (Baksh and Johnson 1990), Agta (Griffin 1984:20), and Netsilik Eskimo (Balikci 1970:177). However, other ethnographies report the persistence of long-term imbalances without any obvious punishment, exclusion or ostracism [Chácobo (Prost 1980:52); Kaingang (Henry

1941:101); Batek (Endicott 1988:119)], although these anecdotes suggest that such imbalances are due to a small number of low producers within the group.

And I don’t believe the society you describe, free of domination, ever existed. Romantics of all stripes have dreamed of a paradise of innocence somewhere in man’s ancient past. Mexican Marxists of the 1920s to 1960s, for example, thought they had found an example of this past Shangri La in the ancient cultures of West Mexico. Richard F. Townsend, writing in Ancient West Mexico: Art and Archaeology of the Unknown Past, describes this fantasy world as follows:

Free from domination by priests and the demands of complex rituals…the ancient West Mexicans had had time to concentrate on “the little things in life.”

[….]

By the 1960s West Mexico seemed to be securely defined as a kind of frontier Eden, a place that had avoided the authoritarian states and empires of Mesoamerica proper.

But none of this was true, as Townsend goes on to explain:

But in the mid-1960s, this tranquil image of ancient West Mexico was disturbed by events in Los Angeles, at the University of California, where anthropology faculty such as Clement Meighan and H.B. Nicholson and graduate students such as Peter Furst and Stanley Long were actually excavating West Mexican sites pertaining to the “shaft-tomb cultures” and their hoards of ceramic figures.

What the anthropologists found was that the ancient societies of West Mexico were far from egalitarian, that they had been ruled by hereditary political and religious elites.

Gauguin also thought he had found his paradise of innocence amongst the more primitive cultures of Tahiti. He idealized these cultures in paintings like this and this.

.

But the reality of Gauguin’s own material existence belied his imagined paradise. Here’s how Diane Kelder describes his stay in Tahiti in The Great Book of French Impressionism:

Suffering from poverty, malnutrition, and syphilis, he contemplated suicide in 1897. Yet somewhere he found the inspiration and the strength to work on this oversized composition [D’Où Venons Nous/ Que Sommes Nous/ Où Allons nous], which he clearly viewed as both a personal testament and a new interpretation of the traditional religious and philosophic view of human destiny. Using a rough-textured sackcloth, he created a friezelike composition whose flat but monumental forms and exotic color create visual equivalences of the peace and harmony he had admired among the Polynesian natives.

I take your point on “fairness,” it was a poor choice of word. But what I was not trying to describe was utopia. Clearly dominance and attempts at domination exist in egalitarian societies for there to be teasing and exclusion techniques, and murder, to deal with them. But the goal of these techniques is not domination per se, but the sustaining of egalitarianism, the maintenance of the status quo if you will. Boehm explores the reasons for this too, which he felt were to do with trust. Hunters need to trust implicitly that their partners on the hunt have the tribe’s interest at heart, not their own ego-based desire for superiority. On the other hand, sustaining a rigid hierarchy requires inbuilt domination throughout the system, the withholding of certain information, propaganda, and so on. These are fundamentally different processes.

I also made no attempt to describe a world without coercion, though coercion can take many forms. Nor is it my position that there was never any suffering in ‘the good old hunter gatherer days.’ I try not to idolize or romanticize anything. What fascinates me about differently structured societies is their effect on human behaviour, the different type of human they produce. It is my aim, in repeatedly drawing attention to this, to demonstrate the flexibility of human nature, not to suggest a return to primitivism. I am not a primitivist, far from it. I was questioning your assertion that human nature somehow gives rise to poverty, and that abolishing poverty means fighting nature.

Finally, biology is clearly important. We cannot raise cats and dogs to play violins or pilot racing cars. Our humanity is a biological phenomenon. What we do with it is cultural, and people like Gandhi and Martin Luther King show the way to a possible future. Only time will tell if we can make it that far. If we fail, it won’t be our genes’ fault, on that I’m certain.

In terms of egalitarianism in the modern setting, as it is enabled by technology and the path of development generally, this kind of thing is roughly what I’m talking about:

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/10/arts/10innovative.html?_r=3&partner=rss&emc=rss

“But it is at least encouraging that the recent rebirth of the resistance to government intervention that prevailed through most of the 19th century has not come with a return to that century’s complacent acceptance of the inevitability of poverty.”

The guy apparently leads a sheltered life. The idea that poverty is God’s punishment for sin (an idea seldom explicitly expressed in public forums, but often in conservative internal communications) lies behind a lot of the Republican Party’s horror at transfer payments and social spending. The free-market utopianism of libertarians and Mellonists also has a moralistic tinge: “liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate… it will purge the rottenness out of the system.” For these two highly influential groups, misery is not merely inevitable, but a good thing, a functionally necessary element necessary for a good society. Voluntary charity for the deserving poor is allowed, but they have to be humble and grateful.

The guy works for the World Bank, and in international developmental economics this misery principle is overridden by the commitment to economic growth and a global market, a commitment motivated in part by the punitive desire to take American labor down a peg.

Liberal and left-center discussions of these topics go off the track when they fail to realize the nature of the opposition. Good intentions cannot be assumed, and a moralistic meanness which is not necessarily disciplined by facts of any kind is a major influence in American politics and, judging by outcomes and trends, to a lesser degree in European politics too.

Well said. Poverty is the necessary stick to rich’s carrot. Poverty is a systemic necessity of scarcity-based economics and cannot be meaningfully addressed within it.

“The guy works for the World Bank, and in international developmental economics this misery principle is overridden by the commitment to economic growth and a global market, a commitment motivated in part by the punitive desire to take American labor down a peg.”

I agree. And the culture war generates mutual hatreds amongst Americans whose primary political goal becomes punishing each other.

Just think how useful it is to promote the “racist white working class” meme amongst east coast liberals when your goal is deindustrialization. It was very clear from the political commentary on mid-west swing states like PA and Ohio during the 2008 D-Party primary how ingrained amongst liberals this particular formulation really is.

When talking — even briefly — about the attitudes of 19th century economists about poverty, Karl Marx really ought to be mentioned.

No. Clearly the most important figure of any century to mention in a discussion of poverty is the 19th century American economist Henry George, who correctly ascertained both the cause of poverty and its solution.

C’mon Yves, is this another one of those “belly-splitting” satirical posts…like the one you posted from the “Harvard Student Economists” last week?

At best, Ravallion is an academic hustler who’s exploiting poverty by using it as a Red Herring to push his Leftist Agenda.

I think that’s way too generous, though. Instead, it appears that Ravallion thinks you are so stupid that he can take your money in a game of 3 Card Monte without the benefit of the 3rd card.

“Follow the ‘Poverty’ Card, Yves. Yes, follow the ‘Poverty’ Card….

Meanwhile, you are utterly ignoring the “Awareness” Card…and looking all the fool for it.

With his “AWARENESS of Poverty Over Three Centuries”, Ravallion asserts that people who lived between 1800-1960 were less “AWARE” of (or less “concerned” with) poverty. He arrives at this conclusion after conducting a Google Book Search.

Are you kidding me??? I am actually embarrassed for Naked Capitalism right now. I blush as I write this. I’m going to tone it down a bit as I feel a sense of pity and compassion. Sure you have George Washington and the Tin Foil Hat Brigade, but that’s obviously because you want to add a little Sensational Spice to your blog. I get it.

But this guy…Ravallion? He is supposed to be legit. He’s Director of Research for The World Freaking Bank for crying out loud….

For the Blog That’s Too Smart to Sleep, this is a MAJOR set-back. It’s Yahoo Chatland-esque.

Before I go, though, I have to address the use of the phrase “Distribution Justice”.

Total bullshit, along the lines of “Family Values”…

Take a belief system, like Conservatism and cloak it behind a “broad, but meaningful” word like “Family”. Then, for good measure, append “Values” to it and voila! “Either you believe what we believe, or you don’t care about the children.”

“Distribution Justice”: Either you are a Socialist or you don’t care about the impoverished.

Gimme a break Ravallion. Are you so embarrassed by your belief in Socialism that you have “Euphemize” it? Does Socialism become “Distribution-Justice-ism?”

How about this as a scaled back, toned down version of mockery and derision, with euphemistic abstraction that even a Leftist Academic can appreciate:

“Guest Post Awareness: Utter Vapidity over the Span of Ten Minutes. Ravallion’s Post Sucked. Justice. And Values Too.”

Actually, given that the net distribution of wealth is from the landless to the landed, either your a (quasi-)Georgist, or you don’t care about the impoverished. (Or you don’t understand the economics and injustice of rent.)

Were you trying to say something, Dan?

Along with Dan (with whom I otherwise disagree) I have to wonder — this can’t be serious. Or else it shows us the fatuity of “analysis” based on a Google search. Did the author only search English language books? What about Saint-Simon, Marx, Engels, What about newspapers?

“Awareness” of poverty most certainly did not decline in the 19th Century. The Revolution of 1848 that spread across Europe was all about poverty.

Increased income disparity caused by the power of global multi-nationals and elites is creating a world we do not want to live in. A world where two thirds live in poverty (basic needs not met).

Awareness is one thing. But what can you and I do about poverty? We are not victims, nor are we uninvolved bystanders, we are participants. We are not powerless, we vote with our dollars, time and actions.

The ability to develop relationships beyond our own family (clan, social class, nation) and connect with others who are different than ourselves is critical. This brings compassion. This will bring solutions to the complex problem of poverty.

This is not an easy task. Certainly it is not an instant or quick-fix task. But neither is it an impossible task. Rather, it takes education, listening, connecting and the willingness to make different choices. Lastly it requires awareness that we are all connected – part of a larger whole – interconnected and interdependant.

Karl Polanyi, in his work “The Great Transformation”, wrote about poverty and origin. Just as Stuarts and Tudors created the laws such as Poor Law 1601 or events such as Enclosures and Speeenhamland law from 1795 and later The Poor Law Reform Act of 1834 which targeted peasants. Today, this abovementioned families can be replaced with some family of nowadays feudals.

“Speenhamlannd was designed to prevent the proletarianization of the common people, or at

least to slow it down. The outcome was merely

the pauperization of the masses, who almost lost

their human shape in the process.”

“The scientific cruelty of that Act was so shocking

to public sentiment in the 1830S and 1840s that the vehement contemporary protests blurred the picture

in the eyes of posterity. Many of the most needy poor,

it was true. were left to their fate as outdoor relief

was withdrawn, and among those who suffered most

bitterly were the “deserving poor” who were too proud

to enter the workhouse which had become an abode of

shame. Never perhaps in all modern history has a more ruthless act of social reform been perpetrated; it

crushed multitudes of lives while merely pretending to provide a criterion of genuine destitution in the

workhouse test. Psychological torture was coolly

advocated and smoothly put into practice by mild philanthropists as a means of oiling the wheels of the labor mill.”

Karl Polanyi – The Great Transformation

If all liberals would read Polanyi’s “Great Transformation,” the cause of human welfare and justice would be greatly enhanced.

Exactly.

As many nations are setting the economic growth targets that will take their populations to the standard of living of a Norway; Brazil,Russia,India CHina, the problem with the current world economy is that there are not enough profits to do this. Hence, unemployment is being exported from these countries and imported into others. Egypt is an example of this. The money being concentrated into the elites of the Arab/OPEC Middle East is not distributed to the larger citizenry nor is any attempt to build even a modest middle class evident, just extreme plutocratic opulence. Dubai anyone. When all of the nations start to move to more egalitarian forms of politics and economics, then there is less for the top, less power for the top, essentially a new world order built on something other than endless accumulation of capital, perhaps built on the endless accumulation humanity.

http://marriottschool.byu.edu/emp/WPW/Class%209%20-%20The%20World%20System%20Perspective.pdf

“You shall not charge interest to your countrymen: interest on money, food, or anything that may be loaned at interest.

“You may charge interest to a foreigner, but to your countrymen you shall not charge interest, so that the LORD your God may bless you in all that you undertake in the land which you are about to enter to possess. Deuteronomy 23:19-20 (New American Standard Bible)

Our current social contract is that the fractional reserve banks shall steal purchasing power from all money holders including the poor and give them jobs and better products in return.

I know this is a radical idea but how about we design an ethical money system that steals from no one? Think that might nip a lot of social problems in the bud? Or is the God who commanded “Thou shalt not steal” mocked? Apparently He isn’t mocked.

Freeing people from poverty goes against Western style capitalism which needs the poor to beat down wages in developed countries.

If there were no poor the whole thing would fall apart.

Where could jobs be outsourced to?

How could Western capitalists pay themselves big bonuses if they couldn’t cut wages?

Ultimately as resources(money/wealth)become more concentrated among the few, poverty is what is left for the rest of us.