By Marshall Auerback, a portfolio strategist and hedge fund manager, and Rob Parenteau, CFA, sole proprietor of MacroStrategy Edge and a research associate of The Levy Economics Institute

Historically, Greeks have been very good at constructing myths. The rest of the world? Not so great, if the current burst of commentary on the country is anything to go by. Reading the press, one gets the impression of a bunch of lazy Mediterranean scroungers, enjoying one of the highest standards of living in Europe while making the frugal Germans pick up the tab. This is a nonsensical propaganda. As if Greece is the only country ever to cook its books in the European Union! Rather, the heart of the problem is in the antiquated revenue system that supports that state, which results in a budget shortfall consistently about 10% of GDP. The top 20% of the income distribution in Greece pay virtually no taxes at all, the product of a corrupt bargain reached during the days of the junta between the military and Greece’s wealthiest plutocrats. No wonder there is a fiscal crisis!

So it’s not a problem of Greek profligates, or an overly generous welfare state, both of which suggest that the standard IMF style remedies being proposed here are bound to fail, as they are doing right now. In fact, given the non-stop austerity being imposed on Athens (which simply has the effect of deflating the economy further and thereby reducing the ability of the Greeks to hit the fiscal targets imposed on them), the Greeks really are getting close to the point where they may well default and shift the problem back to those imposing the austerity. This surely can’t be much worse than the slow execution they are facing today.

In reality, the Greeks have one of the lowest per capita incomes in Europe (€21,100), much lower than the Eurozone 12 (€27,600) or the German level (€29,400). Further, the Greek social safety nets might seem very generous by US standards but are truly modest compared to the rest of the Europe. On average, for 1998-2007 Greece spent only €3530.47 per capita on social protection benefits–slightly less than Spain’s spending and about €700 more than Portugal’s, which has one of the lowest levels in all of the Eurozone. By contrast, Germany and France spent more than double the Greek level, while the original Eurozone 12 level averaged €6251.78. Even Ireland, which has one of the most neoliberal economies in the euro area, spent more on social protection than the supposedly profligate Greeks.

One would think that if the Greek welfare system was as generous and inefficient as it is usually described, then administrative costs would be higher than that of more disciplined governments such as the German and French. But this is obviously not the case, as Professors Dimitri Papadimitriou, Randy Wray and Yeva Nersisyan illustrate. Even spending on pensions, which is the main target of the neoliberals, is lower than in other European countries.

Furthermore, if one looks at total social spending of select Eurozone countries as a per cent of GDP through 2005 (based on OECD statistics), Greece’s spending lagged behind that of all euro countries except for Ireland, and was below the OECD average. Note also that in spite of all the commentary on early retirement in Greece, its spending on old age programs was in line with the spending in Germany and France.

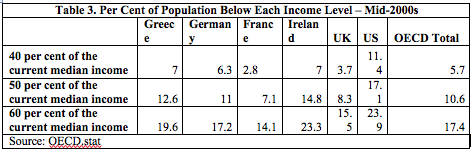

In fact, Greece has one of the most unequal distributions of income in Europe, and a very high level of poverty, as the following table shows (source: OECD and Papadimitriou, Wray and Nersisyan). The evidence is not consistent with the picture presented in the media of an overly generous welfare state—unless the comparison is made against the situation in the US, which is akin to comparing a French impressionist’s skills with that of a 5 year old finger-painter.

Of course, these facts don’t matter. The prevailing narrative is that Greece is, in the words of the FT’s John Authers, “a country that was truly profligate”, with little in the way of data to support that assertion. The country, however, is truly stuck: they can’t devalue, they can’t pay their own way because they do not have a sovereign currency, and nobody will voluntarily finance them. So they must exit and devalue or drop their domestic prices. The massive default, though inevitable, is just a step along the way.

To make the problem worse, export earnings also seem to face their own structural cap that is consistently exceeded by import spending, which means that the debt that finances the government shortfall is increasingly held abroad. The debt is issued under Greek law, but now it is payable in Euros which Greece, as a user of euros, can’t create, given the surrender of its currency and consequent fiscal sovereignty. In this sense, ironically, the fiscal crisis is a consequence of Greece’s success, after a long preparation, in joining the European Union, and hence giving up its own currency, as Professor Perry Mehrling has noted.

The point is that, if this analysis of the source of the problem is correct, then standard IMF austerity policy is unlikely to do much to help. And, as the increasingly intensifying riots on the streets are vividly demonstrating, the patient might not willingly accept the medicine. Despite attempts to turn the country into an economic colony of the EU, Greece is still, after all, a democracy and if one is to judge from the growing unrest in the country, it is far from clear whether Greece (or any other euro zone member for that matter) is really willing to cut spending and raise taxes rates to any degree which will satisfy the Fiscal Austerians dominating economic policy in the euro zone today without at the same time provoking an ungovernable failed state, right in the middle of the euro zone. As J.M. Keynes noted a lifetime ago in a still widely ignored footnote to Chapter 23 of his General Theory:

Experience since the age of Solon at least, and probably, if we had the statistics for many centuries before that, indicates what a knowledge of human nature would lead us to expect, namely, that there is a steady tendency for the wage unit to rise over long periods of time and it can be reduced only amidst the decay and dissolution of economic society.

Of course, Keynes was not a “Keynesian” and in any case, what did he know that the mathematically “elegant”, well-calibrated, dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models of contemporary Nobel Laureates of today cannot tell us?

Even the “Troika” – the European Commission (EC), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the European Central Bank (ECB) – conceded that there might be a slight problem with their Austerian approaches: In a leaked report, from the currently underway EU Summit, and this document will likely form a part of the deliberations in the Greek debt restructuring proposals to be hammered out by Oct. 26th.

On the first page of the document is not only a pretty open and blatant admission that expansionary fiscal consolidation (EFC) has proven to be a contradiction in terms, at least in Greece, but there is also a serious policy incompatibility problem, at least over the intermediate term horizon, with efforts at internal devaluation (ID) – that is, attempting nominal domestic private income deflation in order to improve trade prospects when one has a fixed exchange rate constraint.

While they stop short of recognizing that their demands and the actions they have imposed on Greek policymakers are setting off a Fisher debt deflation implosion of the Greek economy (never mind rupturing any semblance of a social contract, and ripping the social fabric to shreds as well – this is, after all, the jackboot version of neoliberal “reform” designed to stamp out any last vestige of social democracy and organized labor in the eurozone). This is a very large concession for the Troika to have made before the EU itself has taken a “final decision”.

Admitting that EFC is not working, and that pursuing ID will only aggravate matters further, including the ability of Greece to hit fiscal targets, is a fairly large step by the Troika in the recognition of the reality of the situation. This is not something the faith based neoliberal economists in the Troika organizations are often prone to do. It is not what their incentive structures, formal and informal, tend to encourage them to do.

So why pursue it? Well, let’s face it: this has far less at this stage to do with Greece (even as the prevailing mainstream narrative continues to perpetuate the picture of a lazy, unproductive country full of profligates and scroungers), than punishing other potential fiscal deviants and recalcitrants.

Angela Merkel clearly has Italy in her sights. She, and the Troika are scapegoating the Greeks – in order to make sure that should Greece take the rumored “hair cut” on its debt and restructure, the other peripheral countries – especially Italy – won’t get any ideas and be tempted down the same path of forced debt restructuring, but rather will redouble their efforts to achieve arbitrary fiscal targets on an equally arbitrary timeline (and how’s that worked out for Greece?), and learn to “live within their means”, as the Germans always piously lecture the world. This is the strategy to prevent what is euphemistically called the “contagion impact”. In reality, it is also called the principle of collective guilt – destroying the livelihoods of thirteen million people for political or ideological or faith based reasons, which is frankly disgusting and unacceptable. Given their own history, German policy makers should understand this phenomenon. Indeed in many respects, this all too eerily resembles the tangled, twisted mess left by the demands of WWI reparation on Germany – except this time around, Germany is one of the creditor nations imposing their will on the crushed debtors.

If the prevailing mix of fiscal austerity policies continues, there will be spill-over effects to nations that export to Greece. To be sure, Greece is a tiny market in Euroland, but its fiscal problems are by no means unique. As the bigger economies like Spain and Italy also adopt austerity measures, the entire continent can find government revenue collapsing – even Germany, where economic deceleration has become markedly more noticeable in the past few months. As an illustration, consider the ZEW survey results on six month forward expectations for the economy to get a glimpse of where German export momentum may be going. If the historical eight month lead times continue to hold up – and it is certainly tracking right on schedule to date – then the contagion effects on German exports will be utterly devastating by early 2012.

Finally, if austerity succeeds in lowering wages and prices in one nation it can lead to competitive deflation, only compounding the problem as each country tries to gain advantage in order to promote growth through exports. If private debt to GDP ratios did not well exceed public debt to GDP ratios in most eurozone nations, this might not be such a dangerous dynamic to set in motion.

And here we must ask the painfully obvious question: why, pray tell, do all the Fiscal Austerians make a point of ignoring the private debt overhang built up over years of serial asset bubbles in the eurozone? Could it be the faith-based economics that they practice, where fiscal balances express a sort of moral purity, and private decisions are always and everywhere deemed to be optimal and sustainable by definition, a la the magical passes of the Invisible Hand?

What is most remarkable to us is that the largest net exporter, Germany, does not appear to recognize that its insistence on fiscal austerity for all of its neighbors will cook its own golden egg-laying goose. If Germany wants to run a perpetual current account surplus in order to pursue their Asian-like mercantilist, export-led growth strategy, then some other nation, or group of nations must be prepared to run current account deficits ad infinitum. Which means issuing liabilities ad infinitum to the current account surplus nation in order for the current account deficit nations to spend more than they earn on tradeable goods and services. What this means is that default is inevitable unless there is a policy or price mechanism that encourages the current account surplus nation to reinvest the reserves they earn in foreign trade back into productive, income generating capital equipment in the trade deficit nations. This much is elementary international economics, but somehow it completely eludes Berlin.

The German Chancellor and her Finance Minister like to say that no real economic union is possible if one party to the union (Greece) works shorter hours and takes longer holidays than another (Germany). What she should say is that no real economic union is possible if the governing plutocrats of ALL nations (not just the billionaire Greek ship-owners who probably have already moved their money offshore, but also wealthy bankers who have suffered no consequences for their own fraudulent and willfully destructive lending practices) consistently evade their fair share of the cost of that party’s own state expenditure, expecting the union either to pay the bill itself, or to force the bottom 90% to pay it. And there is no real economic union (or any hope of a future political union) if current account surpluses are not properly and sustainably recycled into the trade deficit nations. It would be as absurd as Texas perpetually insisting on running trade surpluses with the other 49 American states.

Greece is not a special case, but rather a case in point of exactly what happens when you impose fiscal consolidation on countries with high private debt to GDP ratios, high desired private net saving rates, and large, stubborn current account deficits. What is needed is a way to redistribute demand toward the trade deficit nations—for example, by having the trade surplus nations spending euros on direct investment in the trade deficit nations. Germany did this with East Germany. Such a mechanism could be set up under the aegis of the European Investment Bank very quickly. Effective incentives to “recycle” current account surpluses in this manner via foreign direct investment, equity flows, foreign aid, or purchases of imports could be easily crafted. If it could be accomplished, it will be a way Greece and the others could become competitive enough to secure their future through higher exports.

Failure to embrace this kind of coordinated, mutually beneficial growth option will ultimately give the Greeks little alternative but to default, leaving the euro zone’s policy makers with an even bigger and costlier mess on their hands. Admittedly, this will not fully solve Greece’s problems as they would like have to leave the euro zone as well and reintroduce the drachma. They would need to reverse fiscal consolidation and place government bonds in their banks as part of their recapitalization efforts. An independent central bank would also have to become a buyer of government bond issuance as foreign demand would likely evaporate for some time. This would entail capital controls, which will cause people to head for the exits (this is, after all, a country with lots of boats) and will require an active mobilization of real resources into public/private initiatives and export enhancement (improved labor productivity, faster product innovation, more R&D, etc. It would not be pretty, it would undoubtedly be painful, but as Iceland is demonstrating today, it is possible to survive and grow and, in any case, is far better than the alternative of starving to death under the guide of the Troika for a decade or more.

In a more dire scenario, a Greek default, would be more akin to a “Sampson moment” for the entire euro zone. Like Sampson in his last days, blinded and beaten by the Philistines, Greece is weakened, blind and bound. Default would represent one last defiant burst of strength with which it “wrecks the temple” (in this case the euro zone) via default and in doing so, it may also take down everybody else.

Myth-making at the expense of the Greeks does not serve anybody’s interests, as there will be a cascade of defaults everywhere, and a Soviet style collapse in incomes, hardly an enticing prospect for the global economy. Not an attractive ending, but this is the kind of outcome which the troika’s self-serving, immoral and cruel policies could lead to before long. The Greeks, and the vast majority of Europe’s citizens, can surely do better than this. The existing policy path is literally bankrupt and bankrupting, and this game of chicken cannot go on for much longer.

As I understand it, if the ECB were allowed to print the money for each country to cover its debts then, since the bank is standing behind the loans, interest rates would fall and save the bankers. But, in order for the EU to grow, there needs to be a EU fiscal unit – a government. Is that correct?

…The top 20% of the income distribution in Greece pay virtually no taxes at all, the product of a corrupt bargain reached during the days of the junta between the military and Greece’s wealthiest plutocrats. No wonder there is a fiscal crisis!…

…The country, however, is truly stuck: they can’t devalue, they can’t pay their own way because they do not have a sovereign currency, and nobody will voluntarily finance them. So they must exit and devalue or drop their domestic prices. The massive default, though inevitable, is just a step along the way…

I know you’re economists and class warfare has gone out of fashion, but if the ailment is a corrupt bargain then, surely, the remedy must lie in reversing that bargain and not in hiding it beneath a currency depreciation. Never let a good crisis go to waste!

This is somewhat in contrast to other things I’ve said here and elsewhere, but I think it’s an important point, and one that stands outside the dichotomy of Neoliberals/Austerians vs. Chartalists/Keynesians.

Clarification: I was trying to say that maybe economists should not always feel compelled to give economic (monetary) advice if the cause of the ailment isn’t primarily economic (monetary) in nature. You should be teaming up behind a Greek version of Bill Black, I’d say. Of course, for practical purposes, there is a case to made that fighting symptoms is as important as fighting causes, so I’ll leave it at that.

Oliver,

Agree totally that this is a POLITICAL problem above all else. Our point is that you cannot possibly rectify the current problem through the policies that are being embraced by the Troika and the core European countries. And it’s not just Greece. Take a look at the latest European PMIs, which were a disaster. Certainly, if there is a recession the body politics will probably lose patience. The French services PMI fell more than five points to 46. Okay, that is a subjective read, but if correct it suggests a sudden broad based contraction. We don’t have the Spanish and Italian PMIs but they were already very low. This overall PMI suggests they fell as well. That would put Spain in outright negative territory. The Spanish government keeps reporting good GDP and other data. They must be deliberately lying about their economy and fiscal deficit (no, that can’t be right; I thought only the Greeks did this!). In any case, this cannot be hidden forever. If they are lying and it surfaces then this whole thing can blow up.

A thousand thanks for this article, sir, and I hope people recall about a year or so ago when Merkel publicly announced they should legislate against naked swaps, and then a big silence and nothing further was heard on that subject?

Of course, this is the attack on the Euro south, and we will probably witness something similar over the next few years in the USA against state and local municipal debt.

Quite probably with the same results.

not true, Latvia did it, and did it voluntarily

The problem is that the problem is not either/or.

There is a broken revenue system leading to a massive under collecting of taxes AND there is a problem with certain elements (not all) of the public sector being overly well compensated.

So there is no one “solution”to the mess. The society needs to “transformed”and this is no easy solution, especially in the middle of a crisis, with everyone looking out for them selves first.

The solutions that could require time (which is no longer available), or a critical event from which there is no escape (drachma return).

Unfortunately the lack of trust in the society makes any solution all but impossible to implement. Greece is still no where close to getting its act together.

That’s all interesting, but, please, explain to me what Greece actually produces to warrant your comparison in wage and income costs to the rest of Europe.

“What this means is that default is inevitable unless there is a policy or price mechanism that encourages the current account surplus nation to reinvest the reserves they earn in foreign trade back into productive, income generating capital equipment in the trade deficit nations … And there is no real economic union (or any hope of a future political union) if current account surpluses are not properly and sustainably recycled into the trade deficit nations. It would be as absurd as Texas perpetually insisting on running trade surpluses with the other 49 American states … What is needed is a way to redistribute demand toward the trade deficit nations—for example, by having the trade surplus nations spending euros on direct investment in the trade deficit nations … Effective incentives to “recycle” current account surpluses in this manner via foreign direct investment, equity flows, foreign aid, or purchases of imports could be easily crafted. If it could be accomplished, it will be a way Greece and the others could become competitive enough to secure their future through higher exports.”

The German capital account deficit already represents funding that is equivalent to a funding/saving shortfall for investment elsewhere in the Euro zone – by accounting identity, of course. But the source of this German capital account outflow is the German current account surplus, which continues notwithstanding any “rule” that might direct outflows from the German capital account. A “rule” for directing those flows will be constrained by the fact of such flows inevitably being deployed in some way with or without such a rule, so long as the current account surplus continues.

If the strategy is to “redirect” the German capital account deficit toward productive investment in a more specific way, then it involves by implication a change in (not an addition to) the investment mix elsewhere in the Euro zone, ceteris paribus. And it involves by implication a reconciliation of flows that originate through the current account surplus with a simultaneous requirement to ration them out through offsetting capital account deficit. It’s seems sort of like needing to exert endogenous control over an exogenous variable.

Put another way, since Greece is running a current account deficit now, it already invests to the point where it “requires” capital inflows. And that balance is quite outside the separate existence of the Greek government budget deficit. So, what is wrong with the existing Greek investment mix that an externally “supervised” investment program will fix? (Not saying there isn’t something wrong – just inquiring what is it?)

From Germany’s perspective, how would this work? Presumably, this involves a change in the way in which investment decisions are made elsewhere in the Euro zone, but controlled in part by Germany. In essence, the German current account surplus starts to carry stronger voting rights for investment elsewhere in the Euro zone. Can you shed a little more light on how such a re-balancing mechanism would work?

Auerback, Parenteau: “The country, however, is truly stuck: they can’t devalue, they can’t pay their own way because they do not have a sovereign currency, and nobody will voluntarily finance them. So they must exit and devalue or drop their domestic prices.”

I respectfully disagree. The ongoing Greek debt deflation should be the right time to introduce stamp scrip in Greek states and communities, converting their debt to public servants and other expenses to local currency, and accepting this local currency from their inhabitants.

As an example the case of the town of Woergl in Tyrol, Austria is useful. In July 1932 Woergl introduced ‘Arbeitsbestätigungsscheine’ (certifications of work performed), a kind of ‘umlaufgesichertes Freigeld’ (free money with guaranteed circulation), thereby following the teachings of Silvio Gesell.

The certificates representing 1, 5 and 10 Schilling had to be devalued with stamps, every month by 1%. Money circulation and economic activity was revitalized, and unemployment was reduced by 6%, while it increased further in other Austrian states.

The experiment ended after 14 months in September 1933 after the Austrian central bank had won its lawsuit against Woergl, and the town was threatened with the deployment of the Austrian military.

The usage of ‘Freigeld’ (free money) in Woergl was even acknowledged by Irving Fisher who recommended it as ‘stamp scrip’ to the US government.

Yes sir. Negative interest is discussed at length in Eisenstein’s “Sacred Economics”. The only things standing in the way are psychological hurdles and mythical “growth” ideologies. Hurry up and spread the word before they capture the world wide web library too!!

http://www.realitysandwich.com/sacred_economics_chapter_12

Pete: very good link, thx.

German trade surplus, ad infinitum, global savings glut, the classic Ben Bernanke paper and TRILLIONS OF USD, domestic and expatriot cash hordes, sitting on the sidelines as a liquidity preference. What we have here is a failure to distribute all of the wealth that has been created, and over accumulated, the surplus profit capital. And now, the liquidity preference brings on the extortionate restructuring of the problem, moving the solution downstream into the 99% of the population that is too profligate. The Germans blame other ethnic groups the way republicans blame greedy unions and minimum wage regulation of business for all of the problems of the world.

But, there will be a return of the business cycle to business as usual, as restructured into THE new normal, shoved down the collective throats of the citizenry of the world. And profits will accumulate, yet again, and be delivered into unprofitable, crisis producing investments of debts, seeking a return of investment that can not be repaid, without the return of the liquidity preference intervening to stop the machines of commerce from grinding, while they restructure to the problem to that someplace else that causes the least problem for the capitalist class, no matter how much annihilation it causes the rest of the world. But, not so easily this time with world wide revolt going on.

Paper Capital is not wealth. If the capital runs to the exit (gold, hard assets, consumption) inflation will explode.

Greece is a stuck nation. Who in their right mind would invest in greece for production ? The market is to small and to open(EU) to invest. The biggest firms are service(telecom,rail) or consumption (Coke bottler) but not export oriented.

High wages compared to the worker efficiency. A lot of strikes and in incompetent tax system coupled with red tape and corruption.

Greece is doomed one way or an other.

Greece has a huge net deficit even without interest and they get a huge 2%(=6 billion)/GDP net cash infusion from the EU every year. Greece has cooked their books and lived above their means for a long time.

They are broke and the other countries wont and cant finance them forever.

Yes, Marshall has caught the awful taste of it. There is a long, long tradition in the history of capitalism, interwoven with the Protestant Reformation, which still haunts it. What made sense at one time in economic history – saving, spending restraint, investment, and which can still make sense at the individual family or firm level, or even under one’s nation’s path at a specialtime, will turn into a mass deflationary austerity disaster when everyone practices it.

This is a repeat of the 1930’s when even left – socialist governments – tried to adhere to the gold standard – which drove them to the same balanced budget directions as Germany, France, Gr. Brit… and the “Center-Right” in the U.S.today.

It was not too hard to see coming; this tale was deeply interwoven with Karl Polanyi’s narrative in his book “The Great Transformation” – from 1944, which I covered in my essay – with a title that resonates with Marshall’s piece here: “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry Market” from Jan. of 2010. You’ll see, thanks to the find anthropological work of Karen Ho in “Liquidated,” that Wall Street had its own “Greek profiligacy” trope which they applied to the old corporate model – all the better to merge and acquire the bloated old firms. Here, still at

http://www.ourfuture.org/blog-entry/2010010211/sinners-hands-angry-market

If Greece defaults, or if the banksters agree to the 50% haircut that’s being discussed, and the world doesn’t immediately end, it will be further evidence that the best policy is to just turn and walk away from these sociopathic bastards. During the Asian Crisis the IMF tried to impose an austerity program on Malaysia, but the PM told them to go take a running leap through a rolling donut. Instead of austerity, Mahatir instituted currency controls and an expansive monetary policy.Their economy rebounded quickly, much more quickly than the other Tigers. And look at Iceland and Argentina? You have to wonder if these criminal bankers understand that their days are numbered (financially speaking), and they are just trying to hold their perverse system together long enough to steal a few hundred more billion before they climb into the get-away Mercedes.

A Greek default would lead to chaos, but nothing like what the Greeks suffered under the military dictatorship. Assuming the Greeks remain in the euro, the final result will be for the population to turn on the rich and privileged and confiscate everything that can’t be moved out of the country. Pensions will be abolished in favor of guaranteed jobs. All real-estate and factories will end up seized by the government and then sold off again to provide revenues and heavily taxed henceforth so that capital receives little and most of the profits go to labor. Human capital will sail through the crisis unscathed, all other capital will be lost. Once the crisis is over, the Greeks will no longer be able to afford imported goods like they are now, but they can still have a high standard of living. People don’t need Mercedes and Iphones and submarines and military jets to be happy.

On the other hand, if Greece leaves the euro, this will allow the powerful to preserve their privileges for a while longer, since inflation benefits the owners of businesses and fast moving speculators.

It is amazing how Germany had all wrong since the very beginning. Profligacy is a side issue: The problem is capital flows from the core to the periphery.

Not addressing the crisis in a symmetric way (demand boost in Germany and other core countries, neutral short term fiscal policy in periphery countries) will lead us all against the wall.

Not to mention the scaring incapacity of our leaders to act…

I am not very optimist…

Well, you can trace this stuff back to Karl Weber (just to mention one) who complained that Catholics were slow to adopt the clock (yes, the clock). Developmentalism starts here, with the designation of populations for discipline at the hands of big capital.

Protestant churches in England, meanwhile, would abandon their anti-usury ideology as, increasingly, they shaped theology around the needs of the emerging system.

There’s a f*cking reason you meet so many missionary nimbuses on the plane to any poor Caribbean or Central American country. All the poor brown people need our expertise like another bullet in the brain.

The subject, as always, is racism, but racism with a purpose.

The purpose of every IMF package ever constructed has never… read NEVER… been to help reform the recipient state into a productive economy in aggregate for its citizens.

Overwhelmingly the prescriptions of the IMF globally have been for states to sell off productive public assets to private interests at fire-sale prices. This of course favors the liquid who have capital on-hand to take advantage of these schemes. The last 50+ years of monetary policy in the G8 have centered around flooding the banking sector with liquidity in the event of crisis.

So the people who propagate these crises are then given the tools to essentially further pillage what little value remains in an economy in crisis. It’s a positive feedback loop of incentives to create crises.

I haven’t yet decided if this is intentionally coordinated this way by the interested parties. It’s possible that it’s a bunch of independent institutions all adapting to the conditions of the system they operate in using myopic policy goals.

Greece spends money in the same ways (basically) that every european country spends. The difference is tax evasion is a way of life there, mostly at the top but really all over the income spectrum. Also, scamming the government, there’s plenty of stories about this.

So if you don’t collect enough but spend the same as your neighbors you need to borrow. Its sneaky though, right, borrow a little more, a little more and then a nasty recession comes along a blam, they borrowed too much.

So the lenders are screwed.

Saying that cutting spending is not the answer is an interesting way of putting it. Its really one or the other, spend within what you collect or enforce your tax code. The cut spending won’t do it idea is bullshit – its an opinion that spending as much as the next guy is the default option.

But this wasn’t any secret to the lenders in the first place. If they thought that this was a problem, why lend? The lenders didn’t properly assess the risk, so who’s fault is that?

“In a more dire scenario, a Greek default, would be more akin to a “Sampson moment” for the entire euro zone. Like Sampson in his last days, blinded and beaten by the Philistines, Greece is weakened, blind and bound. Default would represent one last defiant burst of strength with which it “wrecks the temple” (in this case the euro zone) via default and in doing so, it may also take down everybody else.”

Profound. IMHO, this is exactly the fear that has driven the successive irrational attempts to ‘fix’ the Greece problem based on deep delusions that the ‘fixes’ were mechanisms that would somehow or another (magically in effect) actually have a corrective effect on the unviable Greek economic paradigm – when the mechanisms could not possibly correct the actual technical workings of that economic system.

So basically, “Free Trade” and “Globalism” is an unworkable wetdream of “academics”….funded by “thinktanks”…owned and operated for and by the top 1%?

Sounds about right.

Thanks for the heads up on the real regarding “profligate Greeks”….a very convincing false “narrative” the msm has going in that regard.

The “world is not going to end”…but it sure will be a very different looking animal soon.

The Greeks be tame kittens compared to what 300 million armed and P.O.’d Americans will look like.

When the “Reserve” fiat burns….so will gated communities and ivory towers. And the cops now so full of vinegar and pepper spray, venting on those they should be allied with, will soon be losing their pensions, and will stand and watch the “privileged class” go down….and no amount of useless fiat will motivate them to lift a finger.

Because the US is the 800 lb. Debt Gorilla in the room. Not Greece, not Ireland, not Spain or Italy…..the US stands “supreme.” And will fall like a ton of bricks. Greece is like a small entree before the main course. A “little taste” of what’s sure to follow.

“rf says:

Saying that cutting spending is not the answer is an interesting way of putting it. Its really one or the other, spend within what you collect or enforce your tax code. The cut spending won’t do it idea is bullshit – its an opinion that spending as much as the next guy is the default option.”

Hardly “bullshit or opinion” to state that reducing the amount Greeks (And Italians, and Spaniards, and Irish, etc)have to spend impacts the exports of the country (Germany) wanting to maintain an export surplus…or is that too complicated a concept to grasp?

Simplified: you can’t have your cake and eat it too.

Best bet? Everyone goes back to their own monetary system, and minds their own damn business. And eliminates the concept of “private central banking” and unelected “unions” from civilized discussion.

Including re-erecting the necessary tariff barriers to protect their own citizens…kinda what government is supposed to be about.

Nonsense,why can Latvia do what the Greeks seem incapable of? Nobody forced Greece into the euro, and nobody can force Greece to exit the euro. Stop complaining, stop blaming others, reform or just leave the euro if you think that’s the solution.

Different Eric here. I used to post under Eric, but that seems to be now occupied by Mr. Latvia. I lived Athens a couple of years in the 90s and was impressed by how hard-working many Greeks were. I don’t think they are lazy at all. But boy do they hate taxes. The first full Greek phrase I become aware of was “Is that the price with a receipt or without”? It is pretty lame to contend the main fiscal problem is a deal done back when the Colonels ran the place….or rather, its the same deal these guys have had for centuries! No, the fiscal condition of Greece is what Greeks, operating through their democratic institutions, have elected to make it. They appropriated funds for public purposes, borrowed to have the capacity to meet those appropriations and spent them as intended and prefer not to pay back what they borrowed. The only crisis is that their creditors were so delusional to only catch on the last year or so….it is their crisis mostly. I’m pretty confident that many Greeks are content to let hot-headed youths run wild (down carefully identified streets) for several more months making the case for as big a haircut as possible and then get back to normal life.

You set out to refute the statement that Greece is “a country that was truly profligate”. So how do you explain the very large Greek national debt?

All the complex economics won’t change one, very simple fact. Greece is monetarily non-sovereign. (http://rodgermmitchell.wordpress.com/2010/08/13/monetarily-sovereign-the-key-to-understanding-economics/)

An absolute rule in economics is that a monetarily non-sovereign nation cannot survive long term without money coming in from outside its borders, i.e. without a positive balance of payments.

By contrast, a Monetarily Sovereign nation (like the U.S.)can go on forever with a negative balance of payments.

There are but two solutions for Greece and the rest of the euro nations:

1. Re-adopt your sovereign currency

or

2. Create a pseudo United States of Europe, in which the EU supplies member nations with euros, as needed.

That’s it. Anything else is mere patchwork that continually will reduce the euro nations’ standard of living — perhaps great news for austerity lovers.

Those who do not understand Monetary Sovereignty do not understand economics.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

Hi, I live in Greece and would like more info on the special deal between the Junta and the Plutocracy at the time ie up to 1974.

40 billion Euros is estimated now to be owed by 14,700 businesses and individuals!

Thanks for this. Definitely an antidote for the “Greeks are wasteful” 30 second analysis. But what about the “Greeks don’t pay taxes that they owe” criticism?

There is a consistent thread of this, in more lengthy articles (example: http://www.vanityfair.com/business/features/2010/10/greeks-bearing-bonds-201010?printable=true).

So the argument is not so much waste, but rather setting spending levels that are not supported by revenues, and so funding recurrent expenditure with lines of credit.

That said, the lenders were at fault, and should take their lumps, German and French pension funds and other CDS conunterparties notwithstanding.