James Hamilton, in “Asking too much of monetary policy,” is trying to talk sense to a Fed that just doesn’t get it.

Hamilton ought to have some cred; he proved to be remarkably prescient when he warned in his presentation at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference of the danger of the markets playing chicken with the government on the issue of Freddie’s and Fannie’s implicit government guarantee. He said the markets would play a game of chicken and test the government’s willingness to stand behind the GSEs. He further observed that the US would capitulate and the Fed would be the party that would come to the agencies’ rescue.

Hamilton is now alarmed about the Fed’s recklessness as far as inflation is concerned. He argues that the Fed cannot provide enough monetary stimulus to shore up a fall in housing prices as severe as the one we are suffering now, particularly since the basis for the decline is insolvency, not illiquidity. He also notes that the Fed has stepped to the fore and unwisely taken responsibility for a problem it cannot solve.

The Fed is simply too small an actor, relative to the global banking system, to have enough impact. Consider: one analyst observed that with its new programs (the new $100 billion repo facility and the $200 billion Treasuries-for-MBS facility), the Fed had just creates a $300 billion bank overnight. True enough, but consider: Citigroup’s balance sheet has $2.2 trillion in assets. Steve Waldman estimates that the Fed can take deploy another $300 to $400 billion to similar operations. It can take one more big shot at this problem (ex monetary moves, which Hamilton deems ineffective) before it has used up all its powder.

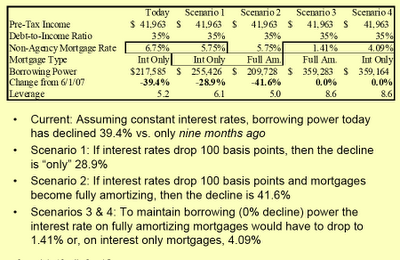

Here’s another way of looking at the problem. This analysis (in a presentation sent by reader Scott) started with a base case of a borrower earning $40,403 in pre-tax income in June 2007 (this was arrived at by starting with a $30,000 income in 1995, compounding it forward for inflation, and then using prevailing mortgage terms to see how much it yielded in buying power. With an interest only loan, a 60% debt to income ratio, a 6.75% non-agency mortgage rate, and no equity, the borrower could afford a home up to $359,139.

This is what you get when you deflate that back to the more realistic terms on offer now (note the income has been compounded forward). Click to enlarge:

It seems odd that the Fed is impervious to inflation risk (or the mere fact that a steepening yield curve, which is what too much cutting on the short end produces, neuters its policies). It may be subject to a phenomenon called incestuous amplification, which was defined in Jane’s Defense Weekly as:

a condition in warfare where one only listens to those who are already in lock-step agreement, reinforcing set beliefs and creating a situation ripe for miscalculation.

From Econbrowser:

I remember a Federal Reserve economist once recounting a conversation with his young daughter, who asked him, “What do you do at work, Daddy?” He answered, “I help make important decisions.” “What kind of decisions, Daddy?” “Oh, things like how much money the government needs to print.”

Which is an important decision, don’t get me wrong. By creating too little money, a nation’s central bank has the power to generate sustained deflation (a fall in the price level), such as the U.S. Federal Reserve did in 1931-33, greatly aggravating the Great Depression, or the Bank of Japan permitted in the late 1990s, undoubtedly prolonging the economic misery of that episode. These were outrageous policy errors, but ones that I am extremely confident that the well-trained fathers and mothers currently employed by the Federal Reserve System would never allow the United States to repeat.

The central bank also unquestionably has the power, by printing too much money, to create ferocious inflation– just ask Gideon Gono, head of the central bank of Zimbabwe.

I happen to be among those macroeconomists who further believe that the Fed can do a great deal more than just cause too much deflation or inflation. The choice for the time path of money creation ultimately determines the time path of short-term nominal interest rates, and indeed the modern Federal Reserve quite appropriately conceives of its primary operating decision as basically choosing the current value for the overnight interbank interest rate, known as the fed funds rate. I would readily agree that careful exercise of this choice could help mitigate– though in my opinion, not entirely eliminate– the ups and downs of real economic activity associated with the business cycle.

I would also quickly point out that an injudicious choice for the short-term interest rate has the potential to exacerbate those ups and downs. Not just the potential, I dare say, but in practice has often been observed to exert exactly that effect. The cycle is an extremely familiar one. The Fed, frustrated by the low level of economic activity, tries to engender an artificial boom through lower interest rates, only to discover soon afterward that this has created more inflation than the public is willing to tolerate. The Fed then has no option other than contract to try to bring inflation back down. But that contraction in turn may prove to be one factor contributing to the next downturn, to which the central bank wants to respond with yet another stimulus. In my opinion, this same pattern has been repeated many, many times in U.S. history, most recently with a Fed that was too expansionary in 2003-2004, which caused the Fed to have to contract in 2006, and that policy-induced boom-bust cycle is part– though in my opinion, only part– of the cause of the problem we find ourselves in today.

So, I am certainly a believer in the potential real effects, sometimes for good, sometimes for ill, of monetary policy. But I just as certainly do not believe, nor should any reasonable person believe, that no matter what the economic problem might be, you can always solve it just by printing more money.

What’s an example of a problem you can’t solve with monetary policy? Suppose you were convinced that house prices in the United States were at the moment substantially higher than they should be relative to the price of other goods and services. How could that have happened, an economist would want to ask, and let’s suppose that the answer is that a credit market profoundly distorted by moral hazard problems loaned vast sums to households that could not reasonably be expected to be repaid if real estate prices stopped rising. The purchase of the properties financed by those loans drove up the price of housing relative to what it would have been (and should have been) with a correctly functioning credit market, so now the relative price of housing must fall.

And why doesn’t the price fall instantly to the appropriate equilibrium value now that these problems are fully revealed, an economist would then reasonably inquire? To which the answer might be, home sellers reduce prices only gradually in a down market, as a consequence of which further price declines are presently quite predictable, as are the additional new defaults that would result from those price declines, as are the consequences of those yet-to-be foreclosed homes coming back for resale onto the market.

The problem then is many hundreds of billions of dollars in loans that are not going to be repaid, the prospect of whose default could completely freeze the market for credit.

That, it seems to me, is a problem you can’t solve by lowering the fed funds rate. Even if the nominal yield on Tbills were driven all the way to zero, the same is never going to happen to the risky long-term housing loans we’re discussing, nor to the rates charged for loans to the financial institutions exposed to the underlying default risk. And even if you could successfully engineer a further reduction in the nominal interest rate charged to home buyers, if the expected real estate price depreciation is large, that would dwarf the effect of the nominal interest rate itself in terms of the attractiveness to a buyer contemplating purchasing a home at today’s prices.

You could in principle solve the problem of overvalued house prices by printing so much money that you bring the price of everything else up to that of housing, generating the necessary adjustment in the relative price of housing without going through the painful cycle of bankruptcies and foreclosures. Whether that is an action you’d want to contemplate might depend on the magnitude of the price adjustment you think is necessary. If we are talking about just 1 or 2% more inflation, I personally would regard the inflation as worth it. But if house prices are today overvalued by 10-30%, for which our proposed remedy is to bring about a corresponding increase in the price of everything else of that magnitude, we would surely want to bear in mind the recent caution from Federal Reserve Governor Frederic Mishkin:

Empirical evidence has starkly demonstrated the adverse effects of high inflation.

Now, reasonable people can and do differ on how likely it is that further Fed rate cuts would help mitigate the current problems. You might reasonably argue that even if the chance of success is small, the cost of letting the economy slip into the cascading defaults that a further 20% decline in real estate prices would precipitate is so large that it’s worth trying anything.

And perhaps it is. But I would nevertheless caution that we need to be open to the possibility that no matter how low the Fed brings its target rate, it may not arrest the unfolding financial disaster. Unless the intention is to go all the way with enough inflation to avert the defaults, that means we need an exit strategy– some point at which we all admit that further monetary stimulus is doing nothing more than generating inflation, and at which point we acknowledge that the goal for monetary policy is no longer the heroic objective of making bad loans become good, but instead the more modest but also more attainable objective of making sure that fluctuations in the purchasing power of a dollar are not themselves a separate destabilizing influence.

I am worried that everyone now seems to be looking to the Federal Reserve for a solution, and the Fed seems to be signaling that it is going to provide one.

Very well said. Americans borrowed and spent; there are people who lent them the money expecting to be paid back. Someone has to pay and someone has to be unhappy, borrower or lender. The Fed can’t change that equation, any more than everyone can have a pony.

He argues that the Fed cannot provide enough monetary stimulus to shore up a fall in housing prices as severe as the one we are suffering now…The Fed is simply too small an actor, relative to the global banking system, to have enough impact.

People seem to dismiss or ignore the possibility that the Fed cares enough about the stock market to do something to prop it up, even though it’s clear that’s what the ’emergency’ rate cut in January was about. Right? The stock market occupies a big space in the average modern consciousness; Fed moves are good at putting a local floor under equities, giving many people a ‘the Fed’s on the job’ feeling of relief while the powers that be try to figure out what to do next. Part of the thinking must be that if equities hold up well enough, then this will mitigate the lost wealth effect of falling home prices.

Yves,

Perhaps you could take a stab at explaining this notion that inflation would somehow close the relative gap of prices – nominally. It makes no sense whatsoever and I don’t get it. It is the same logic as people talking about liquidity not solvency. Inflation in everything but wages/pay expropriates savings and makes people poorer. It does NOT increase your purchasing power. Purchasing power is twop sided: prices and pay. Take a look at the stock market performance in the seventies?

This idea that somehow inflation is the answer is like saying well if we can invent a mortgage that you only pay interest on than the house is worth 800K not 400K. The whole discussion is frankly otherworldly.

Hamilton is a college prof who I’m sure is tenured and has no idea what he’s talking about. These folks don’t live in the real world. They are one step down from the politicians. Blah…blah…blah…and you have his thesis! He’s also liberal as Hell I’m sure.

“Steve Waldman estimates that the Fed can take deploy another $300 to $400 billion to similar operations. It can take one more big shot at this problem (ex monetary moves, which Hamilton deems ineffective) before it has used up all its powder.”

Not true. If the Fed uses its existing asset capacity ($ 800 billion) to faciliate expansion of TAF and TSLF programs, it has the option of going beyond this by issuing interest paying liabilities in order to fund additional expansion. This would sterilize the potential monetary base effect of these programs without any theoretical limit. E.g. the Fed could expand its balance sheet to $2 billion, $3 billion, or more, without necessarily affecting the monetary base or its control over the Fed funds rate.

I meant above:

“E.g. the Fed could expand its balance sheet to $2 trillion, $3 trillion, or more,…”

Yves,

This is a great quote from Bloomberg article on Japanese GDP:

“Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda this month asked companies to raise pay for workers, whose wages have fallen about 11 percent in the past decade”

How funny! Maybe ben should abandon the rate cuts and go begging to Immelt & Co.

The Fed is not printing money. Lowering the funds rate is not the same thing as printing money.

The only money relevant to monetary policy that the Fed prints is excess bank reserves held with the Fed, when fed funds are not trading to target. This is a tiny portion of the monetary base, and even considerably less so of the broader money supply. (The bulk of the monetary base is currency notes and coin in circulation, as determined by public demand, which is an essentially irrelevant variable for monetary policy.)

What is really going on here is Fed asset management. The Fed is starting to intermediate mortgage debt by funding it with the monetary base. As noted above, it can expand this operation if it wants by extending funding to interest paying liabilities.

The Fed has considerable potential firepower to help mortgage market functioning. This is helpful in the sense that it is likely a 2 year problem to sort out correct marked to market valuations and begin the process of squaring these valuations with actual cash flow experience as it begins to hit the books of the banks in its final form. In other words, there is a major disconnect between reasonable expectations for marked to market accuracy and the true cash flow and equity cost that will eventually hit the banks. Parking mortgage product on the Fed balance sheet for a temporary period (even if temporary means 2 years) will greatly assist this process.

People make it sound like housing is the only market that is out of whack. Its actually obvious that other than wages all other price levels have risen quite substantially together. In fact, price of housing relative to gold is at a 20 year low. I think its time for wages – the most lagging of prices – to catch up.

JH parsiong and semantics. The fed cutting rates post sept 01 may not have printed monrey nbut it fdqcilited an explosion of near money and hence the credit tsunami. Host of dicsusions out there on fractuional reserves so leave it to thm. As an aside TIPS spreads negative

JH

I am pretty sure the FED outsourced its money printing operations to the Asian Central Banks.

JH

TAFY is cash to the banks and in theory that money would be lent out or shoved into higher yielding assets to earn NIM. = to inflationary.

As mentioned in earlier comments, very very well said. The implication for home prices is for much lower prices, it has too be.

Does anyone think that wages would rise as much as increased inflation on goods and services? Wouldn’t additional inflation simply put consumers further in the hole, thus aggravating the housing problem?

jh,

This is not a two year problem. The last housing recession (started ~ 1988) lasted 15 quarters, and that was with a Resolution Trust Corporation to force market clearing.

With failure on the individual mortgage level, no easy way to either resturcure or liquidate mortgages due to the way they have been securitized (and the lack of workout skills at lenders; they outsource to credit counsellors), this will take at least as long to resolve.

And having the Fed socialize losses reduces the incentive to have market clearing. We are instead going the Japan route of having zombie financial institutions and prolonged low growth. But Japan at least had a very high savings rate, so they could manage this internally. I’m not sure our friendly creditors will cut us suficient slack.

I’m not sure our friendly creditors will cut us suficient slack.

Without high growth to help support the dollar, this is a real question mark. Remember the talk earlier that the Fed cuts would (pardoxically) stimulate growth and cause the dollar to rise?

Structural sustainable growth rate of US economy is a HUGE issue.

Hi Yves,

Re: The Game of Chicken

Did you see this:

“In reality the Fed is plastering over the cracks until the US Government eventually spends taxpayer’s money stabilising the markets,” said Jim Reid at Deutsche Bank in a note. “Perhaps the markets are trying to force the authorities’ hand sooner than they would ideally like.” http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2008/03/13/11568/cds-report-is-carlyle-the-tip-of-an-iceberg/

So when would the “authorities . . . ideally like” I wonder? After January 20, 2009 so they can try to blame this debacle on the Democrats?