By Tom Adams, an attorney and former monoline executive, and Yves Smith

For those of you who followed the House Oversight Committee hearings on the Fed’s conduct in the AIG bailout, one focus of discussion was the Fed’s efforts to keep the details of the CDOs that the Fed effectively bought via an entity it created, Maiden Lane III, secret.

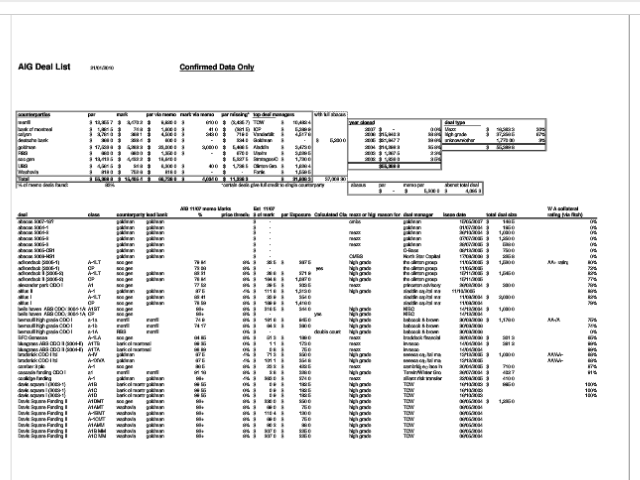

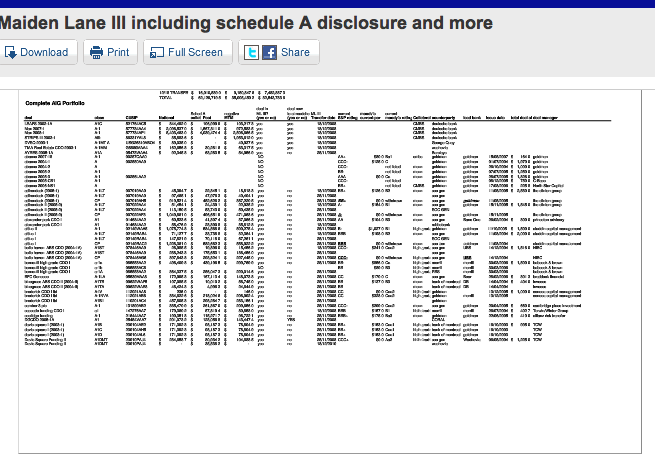

As we demonstrated, these details were hardly secret. The identity of most of the transactions were already public, and from that, considerably more information could be added with not much difficulty from other public sources. We published this detail last week (apologies for the itty bitty print, it’s easier to enlarge from here), with a discussion of findings and gaps.

Yesterday, Darrell Issa, who was the moving force behind the subpoena by the House Oversight Committee which forced the release of 250,000 pages of documents related to the AIG bailout from the Fed, released the notorious Schedule A, the transaction-level detail the Fed was so keen to keep secret, to Huffington Post, which published it.

From that, we have been able to update our work and are publishing the full output of our latest model run. We had already added CUSIPs (which the Fed stressed in testimony yesterday that was something it needed to keep confidential) on 85% of the deals prior to the Issa release,. Getting Schedule A allowed for refinements and corrections.

We indicated in our earlier post that while we did not have all the Maiden Lane III transactions, we had most of them, and this was confirmed by the publication of Schedule A. Of the $62.1 billion in par value, our earlier spreadsheet had all but $11 billion, or 82%, which is consistent with our estimates of our success re capture.

Here is a link to the updated version (which contains more information than Schedule A). Please note that there may be some minor errors; we will go over it again today to double check and correct. In some cases, the print was hard to read, and we hope to resolve anomalies today. For $11 billion of deals added, we also need to add collateral type, year and deal manager; that should also be incorporate today. Some sample output below:

We will be writing up our observations regarding counterparty relationships later today, but one point leaps out of this cut, namely, that for a fair number of deals, the posted collateral is very close to the notional amount of the bonds. In layperson-speak, that means some deals were basically dead already – and they were distributed across vintages and collateral type (excluding the commercial real estate CDOs, which are a small portion of the total). This implies that the other deals were going to catch up at some point. Put another way – if a 2005 high grade deal from one issuer had 80% collateral posting (meaning the counterparty and AIG agreed it was worth only 20% of its original value), odds are high that the other 2005 high grade deals and the 2006 high grade deals are going to get there soon enough (there was enough similarity in structures and underlying assets that the dispersion among eventual outcomes, in most cases, would not be that great).

The fact that some transactions were acknowledged both by AIG and the dealers to be zeros as of the bailout is yet another reason to doubt that these deals would have future upside. That is contrary to both the Fed’s logic in buying the CDOs (see our related post) and its current claim that the deals have traded up despite a massive decay in credit quality. Per a BlackRock memo prepared just prior to the November 2009 decision to buy the CDOs, only 19% were rated junk. Now, according to Moody’s, the more conservative of the two ratings agencies, 93% are rated junk.

Note that the Fed is already engaging in shifting rationales as to why this information needed to be kept in confidence. Its first argument was that the revelation of this information would damage AIG. That was obviously bunk; AIG has limited upside in the vehicle that owns the CDOs (and that charitably assumes there will be any upside). But that was the only line of argument that would fly with the SEC.

The new claim, from the New York Fed’s general counsel Thomas Baxter, is that BlackRock said secrecy was necessary to keep traders from taking advantage of the Fed if and when it decided to sell down the road. But even setting aside how much information was already known and could be developed, the argument is simply implausible. These are unique, illiquid deals; there is no obvious way to manipulate the market in advance of a Fed sale (yes, in theory one could game the ABX, but a sale of this sort is a protracted process, and any party trying to push the ABX around is not assured at all of benefitting by being the winning bid).

Consider: let’s say a bank wound up owning a bunch of apartments because a real estate developer went bust. You know they are scattered across three buildings (some apartments were sold before the developer failed), you know what the developer’s aggregate asking price was, you know the mix of one, two, and three bedrooms; you know the floor plans for one, two, and three bedrooms in each building. You don’t know how many of each type, and where they are situated (ie, which floor, which exposure, which will affect light, views, noise levels).

The bank is going to sell them individually. Thus, the “identity” of each apartment has to be made public for a sale to occur.

Maiden Lane III and the Fed are in a position very much like the bank in question. Even ex the transaction level detail, prospective buyers know the ratings across the portfolio. The names of the biggest deals were disclosed in Maiden Lane III financials. AIG in previous presentations to shareholders provided a good deal of information on vintages and collateral in the residential real estate CDO portion of the Maiden Lane III portfolio. And when Maiden Lane III goes to sell any particular CDO, any market professional has access to the databases that will allow it to look at the underlying collateral (analogous to an apartment viewing).

So how can keeping the identity of the “apartments” secret be of any benefit as far as producing more value in the event of sale? All of the evidence points to the fact that there are other reasons for keeping this under wraps. We’ll continue this line of thought in a post later today once we have tidied up the data a bit more.

Richard Smith contributed to this article

“The fact that some deals were acknowledged both by AIG and the dealers to be zeros as of the bailout is yet another reason to doubt that these deals would have future upside, which is contrary to both the Fed’s logic in buying the CDOs (see our related post) and its current claim that the deals have traded up despite a massive decay in credit quality.”

Hmmm….well that would certainly explain a lot about why the Fed didn’t want anyone to see its backroom deals. I also think the reason it wants the info ‘classified’ as national security issue is simple: otherwise it could become a personnel security issue.

Tom and Yves,

what do you make of Geithner’s testimony that the Fed had no leverage to negotiate haircuts from AIG’s counterparties because it was not willing to let AIG fail? Geithner claimed that all leverage was lost once that became clear to the Fed and everyone else. Couldn’t the Fed have bluffed that it was will to let AIG fall? What other tools or sources of leverage did the Fed have to force the banks to take losses?

and further to that question, Yves/Tom – is the claim that if the Fed had negotiated less-than-par payouts on the AIGFP obligations, this would have constituted default, resulted in an AIG ratings downgrade, triggered other covenants and thus resulted in a downward spiral hell fury of problems for AIG that would have cost the Fed/Taxpayer even MORE to resolve? That’s the key claim that Geithner/Paulson continue to make, which seems “subjective”

KD, Rolfe Winkler of Reuters asked me the same question (and later, a writer from Fortune). This was my response:

Imposing a haircut probably would have been viewed by the rating agencies as some form of “forced exchange” or “selective default” and might have led to a greater amount of capital to be put up as margin. AIG was the patsy in the CDS game of poker. They wrote lots of protection in exchange for seemingly free fee income. (NB: if you dominate a competitive market, and no one else can meet your prices, please ask why you are the brilliant one?) Collectively, the derivative market would take a significant hit from a failure of AIGFP.

Now, the Fed could have said to the traders, “We will stand behind AIGFP on the margin, you don’t have to raise the margin,” and structured the whole thing differently, where the government put AIG into insolvency, and acted as a DIP lender, rather than taking equity ownership, and pumping money into a holding company, and leading to all of the political furor we face today.

I don’t think AIG going into insolvency would have killed the main street economy. It might have had severe effects on the derivative markets and the money center and investment banks. The Fed could have firewalled derivatives trades at AIGFP though, as I said above, and at the time, I might add, and that would have been a cleaner way to do it.

One final note — the state insurance guarantee funds would have taken a whack as most of the AIG life companies would have failed. But those are the breaks. Have MetLife et alia send very nice chocolates and roses to Sec. Geithner.

My “on the record” two cents.

would AIG’s asian operations have failed as well?

Not likely, but I am not 100% sure. There were a complex maze of cross-guarantees, and I’m not sure anyone saw all of them in one spot.

If I may throw my $.02 in – what came out in the testimony yesterday was that one bank (UBS – a Swiss bank) had offered a compromise of 2% but only if the other lenders also agreed to compromise. Many times that kind of conditional compromise is offered when the offeror know or suspects that it is highly unlikely that other lenders will compromise.

NYFed’s General Counsel said that they had limited bargaining power because they were not going to play the “If you don’t, we’ll force AIG into bankruptcy card and they were not going to threaten supervisory action (because they had no authority nor administrative retaliatory action (of dubious impact against the foreign counterparties.” Barofsky, the SIGTARP, thought the Fed could have tried other tactics, like an appeal to the banks’ sense of patriotism or gratitude for being paid out.

Rita,

You don’t seriously believe bankers would take discounts out of “gratitude” or that foreign bankers would take discounts because of “patriotism” to the US, do you?

No, I don’t think so but that’s what the SIGTARP (Barofsky) was suggesting. He also thought that maybe some kind of meeting with the heads of the various banks would have worked but didn’t really address the fact that there were several foreign banks involved.

In spite of all the fog and smoke about CDOs being “too complex” and “illiquid” to correctly value, AIG and its counterparties appear not to experience this difficulty when it comes agreeeing on values for CDS collateral posting purposes.

charcad: I noticed the same thing. I also noticed that there wasn’t that much more collateral to post on most of these CDOs (Wall Street hadn’t gotten around to creating a CDO where you could lose more than 100% of your money, although I bet the Bear and Lehman guys were disappointed that someone stopped them before they had the chance). Given that the government had already agreed to massively backstop AIG, they could have simply given AIG the necessary cash to post as collateral and waited for the market to sort things out. That strategy would have had the benefits of denying banks 100% immediate unrestricted payouts that they did nothing to earn, reducing the amount of cash needed to be devoted to the AIG bailout (since you wouldn’t need to post 100% collateral on the whole portfolio), and eliminating the need for the government to hold a lot of illiquid paper and create a lot of suspicion. I mean, if we’re going to hold a ton of worthless AIG stock anyways, why add a bunch of terrible CDOs in order to hold a lesser amount of worthless AIG stock?

I understand that financially the outcomes would eventually be more or less the same, but putting cash into AIG seems politically and logically sounder than buying the burning houses at full price in order to cancel the insurance policy and reverse the loss reserve.

Does it occur to anyone here that there is a very serious problem with the fact that AIGFP entered into contracts that it could not honor.

Has there been a referral to the Justice Department? If not, why not?

You are onto something there- see Chris Whalen’s work on how fraudulent insurance company “side letters”, after attracting a little too much regulatory scrutiny, were shifted into the CDO business. There was never any intention of paying out these claims, the whole set-up may have been a fraud.

I have a question, please. I don’t know nuthin’ ’bout birthin’ babies or all this financial stuff, but the one thing I noticed was the payout to UBS – it was quite large.

Does this set off any bells for anyone?

I’m only curious because UBS had recently paid a fine to US ($780 million) for hiding tax cheats, right? It was determined that they were complicit in this. And the next thing you know, the tax cheats are going free, the whistleblower is going to jail, UBS is getting a sh**load of money from AIG, and the President of UBS is golfing with President Obama. What’s up with that?

Could the answer be that such “apartments” were simultaneously (and fraudulently) sold into more than one portfolio? (Perhaps Apt. #205 on Elm Street shows up in five separate portfolios.) That would be a good reason not to offer up the transparency of addresses and specific ways of tracking and reconciling inventory.

Considering the extent to which fraud was allowed to flourish, perhaps one has to look at what fraud COULD have been perpetrated all along the way. Then, one must assume that any fraud that COULD have happened–DID happen. Until proven otherwise.

If it was possible for them to have sold the same apartment complex several times over, it must be assumed that this is what happened, until specifically proven otherwise.

Ag Equity Release offers best equity release financial advice, review, ifa, equity comparison, info, reports and equity products. Offer free consultations to allow you to find out more about equity release.

equity release review