By Delusional Economics, who is determined to cleanse the daily flow of vested interests propaganda to produce a balanced counterpoint. Cross posted from MacroBusiness.

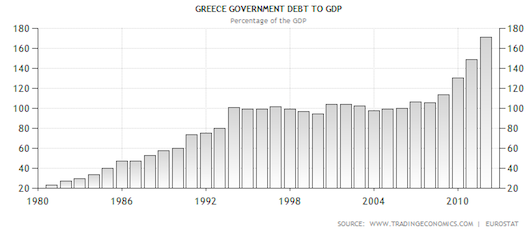

I note that we still haven’t heard from the Euro group meeting about what the exact plan is for Greece. As I said, my expectations are that a ‘deal’ will be stitched together at the last minute to ‘kick the can’ further down the road because I can’t see northern creditors having the political will to admit to their own taxpayers that real losses are inevitable at this time. The big question is whether the IMF is going to accept whatever the ‘deal’ ends up being. But if they are going to stick to their policy that the program needs to credibly deliver a government debt to GDP of 120% by 2020 it hard to see how they can.

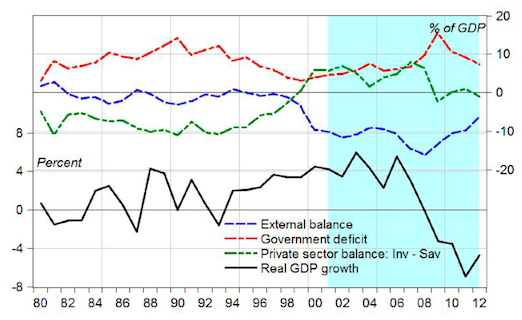

Today I thought it was timely to have another look at the Greek economy from a sectoral balance perspective which will hopefully provide some clarity on exactly what we are seeing in Greece, but just as importantly also provide some broader context to the likely outcomes for other Eurozone periphery nations with similar economic dynamics.

As you maybe aware, my overall assessment of the current Troika programs is that the policy implementation is far too one-sided and simultaneously forcing large fiscal adjustments on euro-bound nations that are already highly indebted and possess structural current account deficits is likely to be counterproductive without significant debt write-downs.

The premise for the Troika programs is that internal devaluation will make supported nations more competitive and therefore lead to an export driven recovery. This however, ignores two points.

Firstly, without investment in the tradeable sectors to support the structural transformation and increased productivity the only point of adjustment is wages and employment which means that servicing existed debts held by the private sector becomes impossible (I discuss this point here). Secondly, if large sections of each countries export sectors are all attempting the same thing there will be significantly lower external demand to support this adjustment.

The likely outcome therefore, as I’ve covered previously in terms of sector flows, is:

So with the external sector in this state and the private sector unable and/or unwilling to take on additional debt as it attempt to mend its balance sheet … the only sector left to provide for the short fall in national income is the government sector. If it fails to do so then the economy will continue to shrink until a new balance is found between the sectors at some lower national income, and therefore GDP.

It may appear logical to you that this must occur, and I don’t totally disagree, but that doesn’t change the fact that under these circumstances there is simply no way that the private sector will be able to continue to make payments on the debts it has accumulated during the period of significantly higher income. This is a major unaddressed issue.

If we look at the data in the case of Greece this is exactly what we see.

As you may notice we are now seeing a reversal in the external balance which means the current account is starting to move out of deficit. In fact over recent months the Greek government has been reporting a current account surplus:

Greece’s current account balance showed a surplus for the third month in a row in September, when it reached a surplus of 775 million euros, compared to a deficit of 1.1 billion euros a year earlier.

“The trade deficit fell by 700 million euro, as a result of a 512 million euros decrease in the trade deficit excluding oil and ships, as well as declines of 68 million euros and 120 million euros in the net import bill for oil and ships, respectively,” said the Bank of Greece in a statement on Monday.

“The trade deficit excluding oil and ships shrank due to the considerably reduced import bill (down by 726 million euros or 30.3 percent), despite the fact that export receipts fell by 213 million euros or 15.9 percent in September 2012.

This sounds positive but , as always, concentrating on a single metric can give false impressions and it is important to understand exactly what is occurring “under the hood” as it were.

What you may have noticed from the sector chart above is that Greece has had a fairly long running current account deficit, which started to accelerate in the second half of the 90s. This corresponded with the move to a negative net saving position by the private sector and also a marked increase in GDP growth. What this implies is that the private sector began to take on increasing levels of debt funded through external borrowings, which also allowed government deficits to begin to fall over the same period while the economy grew.

Followers of the Australian economy may recognize this dynamic as similar to the “Howard years”. The problem is, of course, that this is GDP driven firstly by a dis-saving in the private sector and, if continued, increased private sector indebtedness. As we know, again from Australia, this can continue as long as direct investment, portfolio flows and net lending to the financial system from foreign sources continues, mostly via surplus recycling, and the private sector is willing, and able, to continue on this path. This is a major concern for Australia in terms of the end of its capex boom (I discuss this here) but a point of difference is that Australia has a cushion of a floating currency in regards to its creditors, Greece does not.

As you can see from the chart this all came to a screaming halt around 2007 when the GFC struck and Greece’s private sector was forced to re-enter a state of net saving. This was initially met by an increase in government deficit but austerity programs quickly turned this around and, as I explained above, this led to a situation where the only possible outcome was a fall in GDP while the sectors found a new equilibrium.

Debt of GDP is quite obviously governed by two factors of the level of debt and GDP growth and with the later falling rapidly ,and transfers from the private sector to the government made impossible by existing indebtedness, the only possible outcome is what you see in the chart below:

So what does this tell us?

Firstly, it shows that the Greek crisis was not just an issue with the government sector, but was likely caused by a long running structural issue in which economic growth was being funded by increasing foreign borrowing by the private sector.

Secondly, although the current account is now approaching surplus it is nowhere near the required magnitude to drive economic growth. Without renewed private sector indebtedness or an increase in foreign investment, both unlikely, GDP will continue to shrink driving national debt to GDP higher. Although the current Troika plan hinges on a growing current account surplus led by exports, subdued external sector demand from Greece’s existing trade partners make this unlikely.

Thirdly, given that both the government and private sectors have been net debtors to the external sector the write-down of existing debts or the transfer of non-financial assets is really the only way meet the current parameters of the Troika program.

Fourthly, Australia can learn some lessons from this woeful episode of financial mismanagement.

greece is not austria and will never be austria…greece is florida…sun fun…(not as many guns)…

Cyprus gets the attention, but the oligarchs of greece have kept the property ownership database a mess for over 30 years…this insures a barrier for building retirement homes for europeans…

physically, greece could sustain 100k new homes being built every year…(for non greeks)…greece probably has more coastline around its thousands of underinhabited islands than can be filled by blue haired europeans…and with so many mountains everywhere, its like living in the oakland hills…so suggesting that greece needs to be like…germany…is like suggesting florida will never be too popular since it has a limited rail system and it is too far from the center of the USA. Why try to fit the fat chick in spanx two sizes too small ?? The problem with greece is that it is run by greeks…greeks who have no vision…the country is led by mostly corporate carabinieri who have wormed their way to the top…they dont see how easy it would be to write ESOP legislation and allow fresh money to enter greece from the sale of 100k retirement homes per year…the leadership is still waiting for the bell bottoms in their closets to come back in style…who loves you baby…???

The loudmouth union leaders need to go visit Lula in Brazil to see how the left was won, and need to hire UPS to share with them how an ESOP works…

and since when does the IMF know what it is doing…???

what country, exactly has heeded its calls word for word and magically became a challenge to the US or China ??

Hi alex, yes, Brazil does seem to offer something close to a viable alternative. I’m worried though that it’s success is in part covered by the resource boom. Maybe another example — and I’d be interested if you’d agree with me or not here — is Argentina. Now, for a Brit, that’s not a happy recommendation ! But I am beginning to wonder if maybe, in spite of some pretty big reservation I have about Cristina Kirchner, whether Argentina’s in-yer-face approach to the banks isn’t worth more study. I get into enough trouble here commenting on the US, so Latin America is where I fear to treat ! That’s why I’m interested in other opinions…

Clive, you might find the US military intervention into South America’s southern cone interesting, which is being undertaken under the pretense of the ‘War on Drugs’. Aldea Global (Global Village) did an excellent report on what’s going on in the region in its October edition:

“The war on drugs: US strategy of control in South America”

http://issuu.com/lajornadaonline/docs/aldeagl02102012/1

The article is written in Spanish, but I will try to give a synopsis.

Several countries in the region (Chile being the only exception) have adopted economic policies which run counter to the neoliberal polices which the US is trying to impose. Argentina, under an expansionist neoKeynesian government, has increased public investment and is on the road to becoming an interventionist state, which has caused tensions between it and the US and US/NATO-dominated international organizations like the IMF and World Bank. Brasil also has taken a protectionist tact, increasing tariffs on 100 products and constantly limiting imports in order to guarantee employment and protect domestic industry. Uruguay has also resorted to protectionist measures, and has committed the ultimate crime in the eyes of the mandarins of global laissez-faire: it has legalized the use of marijuana.

In reaction to this, the US engineered the overthrow of the government of Paraguay and, with the permission of the newly installed government in Paraguay, dispatched US Navy SEALS to conduct maneuvers in the Chaco province of Paraguay. The justification the US uses to justify this military intervention is to fight the war on drugs. The veiled purpose, however, is to intimidate Argentina and Brazil and to destabilize the region so that the US can reassert its dominion over the region.

There’s nothing new, of course, about the liberal internationalism being imposed at gunpoint by the United States and its NATO allies around the globe. I would point you to Kevin Phillips, who in Wealth and Democracy observed of the openness of the world economy from 1870-1913:

Of course we all know how that movie ended: WWI, the Great Depression and WWII.

ww1 began becasue of fanatical, pan European, millitarism and 18th politics colliding with 20th century weapons..the great depression happened because there were yet few or no policie regulations and actuall physical infrastructure (power plants, highways, airports ets.,) in place to prevent or mitigate the all too predictable results of a 10 year specualtive stock bubble bursting…ww2 was mainly the continuation of the festering, smouldering, unresolved conflicts of ww1 – in addtion to aggressive Japanese expansion in the Pacific.

Not quite.

World war one began in the context of imperial carve-up. Britain and France, along with others including the US of course, ran what the people of their empires would recognise what you call regimes of fanatical militarism (ask the Filippinos about US militarism on the eve of the 20th century). Germany wanted a larger piece and had been constrained for years by France and Britain – not for reasons of altruism. So yours is a plausible statement only if you include both the British and French as chief underwriters of that militarism.

World War two in the Pacific has a similar basis. Japan was doing the western schtick of subordinating other nations (Manchuria and China) when hostilities with the west began. They began with US and European shipment of materiel, pilots and training to Burma and China (an act of war by the western imperial bunch after which Japan took over Vichy Indochina) and then in the form of an embargo on Japan (another act of war) by Dutch Indonesia, Australia, Britain, France and America of supplies of iron and steel and of rubber in 1941. Japan’s assets were frozen in the international banking system (ie America).

Stimson, Sec. of War dairy entry November 25 1941, “The question was how we should maneuver them [Japanese] into firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves.”

The attack on Hawaii, Malaysia and the Philippines was in reaction to this threat to their ability to wage war on mainland Asia. The blockade took place because the West was protecting its racist, militarist, industrial/government (fascist, if you like) empires – and its Chinese business interests. Not much different to Japan, just there first.

The original sin is empire and the state-of-the-art sinners before both wars were the British and French and then (WW2) the US. Holland, Germany, the Austro-H empire, Japan and other empire builders or losers simply wanted by force what we took by force.

Clive,

There’s another article in that same edition of Aldea Global that you might find of interest. It alludes to the market fundamentalism that inheres in neoclassical economics.

In the neoclassical view, markets are an embodied rational will: the social world is governed by an “invisible hand” that miraculously produces a rational distribution of goods and services. The dissident view, articulated by folks like Hyman Minsky and Steve Keen, asserts that markets are highly irrational and prone to large swings in sentiment, ranging from “conservative” to “euphoric” to “ponzi.” As Steve Keen puts it, the “rational expectations” of the neoclassical economists means “never having to say you were drunk.”

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2012/05/22/predicting-the-global-financial-crisis-post-keynesian-macroeconomics-2/

The real-world effects of the neoclassical economists’ delusional and absolutist faith in markets have proven disastrous. The modern neoclassical economist is very much cut out of the same cloth as the medieval scholastic, the only difference being that the orthodox economist believes in the omnipotence and infallibility of markets, whereas the scholastic believed in the omnipotence and infallibility of God. Overstating the absolutism is impossible. The Church has become “a faithful and ever watchful guardian of the dogmas which have been committed to her charge,” wrote San Vincent of Lerins. “In this secret deposit she changes nothing, she takes nothing from it, she adds nothing to it.” “The Catholic Church holds it better,” wrote a Roman theologian, “that the entire population of the world should die of starvation in extreme agony…than that one soul, I will not say should be lost, but should commit one venial sin.” We now see this extreme absolutism reemerge in neoclassical economists, such as what is occurring in Spain before our very eyes:

Many thanks From Mexico. Appreciate the translation, these articles are worthy of a wider audience. And also, yes, you’re right to mention Britain’s “form” on this one — the Empire was mercantilism plain and simple. Ultimately, of course, unsustainable. But brought to and end, ironically, by US hegemony.

Thats not a “happy” recommendation for anyone, except maybe European and American banks

IMF “knows” exactly what it is doing-read history-(John Perkins) “Confessions of An Economic Hit Man”, and “Hoodwinked”:

http://www.thriftbooks.com/viewdetails.aspx?isbn=0452287081

http://www.thriftbooks.com/viewdetails.aspx?isbn=0307589927 (2011 edition-this is 2009)

IMF INTENDS profiteering..let’s not forget Goldman-Sachs involvement in Greek “debt”:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/feb/18/greece-goldman-sachs-debt-derivatives

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/7318877/Goldman-Sachs-faces-Fed-inquiry-over-Greek-debt.html

Alex, why yes, why didn’t I think of that, turning Greece into Florida? I don’t want to pretend to an expertise in Greek national character which I don’t have, but I have a few nagging suspicions from fragments I’ve picked up over the years that this might not sit too well with the Greeks. (And which Greeks, the society is stratified just a wee bit, I hear…Balkans excepted, didn’t Greece have the most recent Civil War in European history, at the end of WWII?)

I think that perhaps because Greece has abundant natural energy resources – potential now – not brought to fruition – and a pretty broad agricultural base still (and remember the old prescriptions for “modernizing”: shrink the numbers engaged in Ag and export like crazy)they might have a shot at the Argentine model; no easy go and still lots of change and adaptation…but more on their own terms. Just can’t see globalization and foreign capital inflows on the 1990’s model working out well for the periphery – and you have stated some of the reasons.

Blue haired Europeans? that’s a really good typo

At the risk of being boring he is talking about Australia – 20 million people sitting on piles of rocks in the sun strewn across 3 million square miles.

NOT Austria – former home of the Hapsburgs emporers and now best known for skiing and a Rin Tin Tin copy called Inspector Rex.

A really excellent feature Delusional. You’ve covered all the bases.

Here in Europe, we get subjected to regular doses of hopium about “EU leaders are working on a solution to Greece’s problems” or some such. As you rightly point out, it’s really not that difficult to understand. Even people who wouldn’t think of reading NC get it. The available options are:

1) A significant step-up in exports. To which the reply is “Of what ? To whom ?”

2) Lots of Foreign Direct Investment. To which the reply is “Why Greece ? Why not (insert country of your choice here)”

3) A competitive currency devaluation. Been declared as off the table.

4) A default.

Instead, what’s being attempted is an internal devaluation. But that is really 1) above in disguise. It has the same problem.

As many NC features have pointed out, for underwater but otherwise solvent home owners — and pretty much any other class of borrower in fact — a modification of your loan is the least-worse solution.

I’m not expecting anything other than many years of continued can kicking.

The euro was all about increasing efficiency over redundancy (manchester economics)

But unlike Manchester in the early 19th century more energy products (corn back then) is not flowing from external sourses to blow down internal monopolies.

However the euro pack wishes to destroy internal monoplies anyway leaving a nothing really.

Europe cannot function under this level of complexity as there is simply not the energy density available to do this.

After 1986 and the single european act these former nations internal rational trade collapsed – to be replaced by the external oil / corn melange .now the oil is gone and they have no national currency to continue as a positive medium of exchange that can adjust to the new circumstances these societies are and will implode.

The Greek oil balance has not moved much in 3 years , but its capital account is being destroyed so as to drive it into current account surplus.

I see this in Ireland also – you now have a division of people

1. who cannot afford the bus

2 that can afford the capital expense of a car and sometimes a expensive German model.

A dramatic stratification of society because of its use of a external hard but brittle

currency.

Interesting Graphs in this energy report although it has that special euro trash blandness about it all.

http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/newsroom/cf/_getdocument.cfm?doc_id=7657

It completely misses the point of course – with a obscene emphasis on efficiency over redundancy but if you equate efficiency with banking leverage and profits this makes perfect sense.

The euro experiment can be seen as a series of onion rings with successive wage / money / energy deflations starting from the core pushing out to the PIigs and their credit / energy inflations and to the Brics now obscene overcapacity.

This started a very long time ago with for example our Irish banks using core fiscal / agri money flows to increase their leverage / credit malinvestment base with a huge waste of capital during a major agri / car boom in the Ireland of the 70s which went bust in the early 80s.

The article of course fails to understand that only national sov goverments printing money for local trade use can we relocalize rational domestic demand & investment and prevent this mindless capital export / destruction from one former nation to another.

In this CSO graph you can clearly see the effects of the Suez crisis in 1957 (first post war credit oil crisis ?) and the capital destruction (capital going up into fumes as the banking system increases the credit money supply and destroys capital.

New private Cars reg

Y1971 : 51,803

Y1978 :105,582 (peak)

Y1987 : 54 ,341

http://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=TEA10&PLanguage=0

I find it interesting that no one seems to ask the one question that alleviates the need for any other discussion on the subject.

That being where does interest come from? I have thought about it since I was a child. I just never got or understood any of the explanations on the subject because money is, of course, inorganic and therefore it does not and cannot grow or multiply.

Ok so if we know that money is created from thin air. That the value of money, particularly in the case of a loan, is really the degree of faith one might have in the value of your signature predicated on an opinion of whether, or not, you will, God be willing and the creek don’t rise, pay back any funds borrowed. Made by those who collect data, from merchants who report, and conversely, hopefully, reporting correctly, about your transactions and your honesty or dishonesty in dealing with those merchants.

Thus, this would explain why we have bubbles and the parallel consequences of crashes after, starts, and therefore it starts to become crystal clear. You can’t pay interest in a fixed monetary system; as each dollar created is a loan, a debt, meaning that all money created is already spent before it’s ever even printed.

Money isn’t really needed in the current modern system created, and bubbles and crashes were infinitely harder to control and execute before we, the world in this case after WWII, allowed ourselves to authorize our Governments, in some, most if not all, this wasn’t a choice given to the people it was just taken. In the case of America it was done without Constitutional authority to do so. We allowed our monetary systems to be run by others and are finding that their interests don’t match ours.

Bubbles and crashes are much easier to control with money that has no fixed real property value to it until the people started tying their homes to it….. get it? Then it has value, but, before it had no real value but belief and that was wearing thin with the people. It’s not fixed to anything that allows one to control the amount in circulation or understand and point to a quantifiable reality based object or standard of measurement as to its intrinsic value as relating to anything at all.

Therefore the only real reason for the crashes and the bubbles that precede them is that once you have all that money in circulation, built up by the bubble, while it may worth less in the short term, its value, will increase over time if they didn’t blow things completely up (I.e. Bosnia, Argentinia, and lately the whole damn world) and therein lies your interest on the money you gave the bank to save for you.

This, would seem to be, a very expensive, way, to save money if you ask me. If your money doesn’t multiply under your bed, when, you save it; why would it do so in the bank? Magic? No you lent yourself the money, actually credit, and you paid yourself the interest on any money saved when the bubble crashed.

Which is why Banks don’t really want people saving anymore, it’s then that people start to figure out the screwing they are getting for the, alleged, privilege of someone assisting them in having others believe them when they say they will pay the bank/loan shark/etc… back. Because someone will always ask how does the inanimate inorganic un-living give birth.

This, all, then would have to be a lie, wouldn’t it? When we know that the jobs are being sucked off overseas and that no one in Government does or will do a damn a thing to help the people of a country only the corporations. Corporations who pay nothing in taxes, suck off the public teat that unlike Social Security that does not cost the taxpayer anything in our budget it being a separate, by law, funded government organizations.

Corporations (Banks are Corporations too) take everything in value for essentially nothing in the end. So I guess that’s apropos that this loan, credit really, is then converted into this cartels means of using said credit. Credit cards, debit cards, Federal Reserve notes (cash), checks and various other financial sector monetary instruments and therefore it’sthe epitome of that old song “nothing from nothing equals nothing …. you gotta have something if you want to be with me.”

Right now folks we are getting bent over and the only ones saying any different are the ones who profit the most. If we want a war in this country and in the end a world war to beat all others then we just have to let the banks continue to do as they do.

FFC, three years ago I would have thought it was irrational to think that social unrest could lead to another civil war in this country. But after watching the Middle East go up in smoke, followed closely by the European nations and knowing civility here is so parched that all it will take is one match, I actually do worry, seriously worry, about an uprising – inchoate or otherwise – right here. Governments no longer govern. It has become a lost art.

Alas, ditto Susan.

I don’t know when I began to wonder just how far-fetched it might be to consider what steps might be taken should even relatively minor unrest break out. Here in the UK we have a long tradition (like, many, many centuries) of general civil obedience.

But in this interconnected and thus vulnerable world, things get pretty fragile pretty quickly.

Thinking about it, two events probably crystallised my change of mind. One was the bank run on Northern Rock (where internet and even humble telephone access to your bank account facilitated a hither-to difficult to bring about rate of withdrawal. The other was the revelation that industrial unrest brought about by the economic turmoil of the 1970’s caused serious planning to be undertaken for the introduction of a “State of Emergency” http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/SearchUI/image/Index/C11493667?index=3&page=1&source=16377

You wonder sometimes, we’ve come so far, achieved so much. But the wrong circumstances conspiring in too short a timeframe, it’s not really robust.

The tragedy is that these things can usually be avoided because someone has foretold it (or several someone’s).

About Greece’s catch 22: if the private sector is not indebted the economy will fail due to the fact that it will be so crippled it will reach a point of no return and slide into poverty. Maybe that has already happened. But it cannot run a deficit because it no longer has sovereign money. So it must borrow from external, foreign sources, who will no longer take that risk. (In fact create the conditions for default.) So Greece can only default and try to make it up by forking over its islands and its gas and oil fields. With everything going on in the Middle East and North Africa right now, and also the South China Sea, it isn’t unreasonable to conclude that this was the intended outcome for Greece, and Greece’s natural resources were considered for 10 years to be sufficient collateral. That, sadly, no other solution was ever considered. Watch out Brazil. Don’t dismantle those missiles yet Russia.

The Greeks can perfectly well default and refuse to make anything up. They can then announce that they are not leaving the Eurozone (for the advantages), or that they are leaving the Eurozone (for different advantages), but the Germans have no say in the question.

Thanks. :)

But what about Germany, et al.? The system includes them, as well. If Germany is going to impose draconian measures on Greece, but wants to preserve the Euro zone, shouldn’t Germany spend money in Greece or import from Greece?

“Although the current account is now approaching surplus it is nowhere near the required magnitude to drive economic growth.”

Here in Europe, we have started to see Greek products for sale. I Am not kidding. We never did. And this is important.

Some rebalancing is taking place.

Alas, the exports from Greece are of course all too limited at this stage. That is not the case for Spain and Italy where the external trade is on the mending side.

“GDP will continue to shrink driving national debt to GDP higher.”

As opposed to Spain, where the problem is now essentially political (breakup), Greece is of course not on the mending side.

Alternatives to the current situations? They certainly can leave, default and pay their imports cash (oil).

That is up to them. Most Europeans would not mind a confident Greece on their own at their footsteps.

Will they do it? I have doubt about Greek citizens being confident in their own governance for some obvious political reasons.