Yves here. This is Lambert’s pick, but since I still remember my two years in Sydney fondly, I thought I would comment. Australia is often stereotyped as being 20 years behind the US in a good way: it has a commitment to collective good, a sense of community, and a robust middle class, things that are increasingly wanting in the US. And it has those qualities along with better broadband and first class, cheap healthcare (the offsets are getting used to the seasons being the reverse of up North, having to adopt a footie team, dealing with the onerous documentation requirements of their tax authority, and having most movies get there after you can see them on international flights).

The interesting quality of this article by Houses and Holes is its sense of consternation about what looks like rising corruption in Australia. I don’t mean to sound condescending, but being in a country so much further along in this ugly process, there’s an underlying trust in authorities and process evident in this piece, while those sentiments are in tatters in the US.

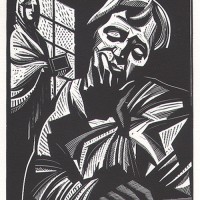

Most societies have a level of crooked behavior that they tolerate; the assumption seems to be that these dirty backchannels are sometimes the only efficient way to work around obstacles, and that enough bad guys will be caught and punished to keep the dubious dealing at a manageable level. You can see here a quiet sense of horror, as if someone in a movie sees their hand suddenly changing into something they don’t recognize as human and realize they may be undergoing a fundamental, chthonic transformation.

By Houses and Holes, who is a regular contributor at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and The Drum and is a former commentator atBusiness Spectator. He is also the co-author of The Great Crash of 2008 with Ross Garnaut. He edits MacroBusiness. Cross posted from MacroBusiness.

In his greatest work, Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky tells the story of Rodion Raskolnikov and his decision to kill an unscrupulous pawn-broker for her cash. Raskolnikov is an aspiring medical student and he rationalises the murder by the greater good that the money can do if it is in his hands. What follows is the finest psychological thriller in world fiction as Raskolnikov is pursued by the authorities and his conscience alike across the ravaged landscape of Western rationalism.

Dostoyevski’s main theme and point was to attack the radical thinking of Russian nihilism; to cut a long story short, those politicians of his day that were driven by a credo that the ends justified the means so long as enough impoverished folk benefited. Dostoyevski was no communist.

But the story is broader still and holds important lessons also for capitalism. Indeed, radical rationalists in all forms are the book’s target, and that can just as easily apply to those on the Right as it can the Left. Which is why Dostoyeski’s work has something to add to an assessment of the current state of Australian capitalism and business. As an entrepreneur myself, I understand the compulsion to bend (and sometimes break, eek!) the rules, to push a business forward. Sometimes rules, legal or ethical, do get in the way of common sense business decisions and it is very easy, and sometimes actually right, to push back the boundaries for the personal and the greater good. But there is also the danger of misjudgment by these ubermensch and over time these mistakes can add up to a softening of the values themselves.

We have just now a range of high-profile scenarios playing out in Australian capitalism that Dostoyevski may recognise as a symptom that something has gone more fundamentally wrong with the values that underpin a rules-based liberalism that balances the benefits of individual merit against the collective need for behavioral norms. In the public sphere, the scandal engulfing the highest levels of the RBA amid bribery charges surrounding its note printing offshoots is a case in point. One has to question the process of accountability handled by the bank. According to Glenn Stevens last week, the RBA did not disclose the details of its internal investigations in 2007 to government until the story broke in the media in 2009. Nor did it ever refer the issues to the police. Ever since, the RBA has been dogged by accusations of obfuscation. Finally last week, the most senior RBA executive responsible, Ric Battellino, acknowledged in Parliament that the police should have been notified and Glenn Stevens admitted the bank’s handling of the affair “was not good enough”. Is this enough accountability? I don’t know and Ric Battellino has retired anyway, perhaps taking some sting out of the fallout. But the fact remains, lack of transparency in a regulator can only erode business probity more widely.

In the private sector we have two other recent high-profile examples of unaccountable behaviour. The first has been the recent convulsion of blame-shifting to labour the cost blow-outs in the oil and gas sector. While labour costs have certainly played a role and unions have too, more important has been the decisions by executives to charge into moon-landing levels of capital spending all at once. As a result they have inflated asset prices, as well as input costs for everything from welders to tires. That many in this same sector so violently opposed the resource rent tax, which may well have eased some of this cost inflation, is one irony. The other is that we have seen this story before (it is called ‘a bubble’) and it will hopefully culminate in a shareholder rebellion that holds those executives who have destroyed value to account.

The other recent example of unaccountable behaviour brings together both public and private spheres in the ongoing Qantas imbroglio where former CEO Geoff Dixon is attacking the national carrier’s current management with a view to destabilising it for his own purposes. This is all to the good and if the market backs a better strategy championed by Dixon then that’s progress. But doing this from the chairmanship of Tourism Australia, a taxpayer funded organisation that had very large commercial contracts with Qantas, is a conflict of interest, as Qantas management has made plain. As Tourism Australia moves to negotiate with a new commercial airline partner, how can the public have faith that its chairman has their best interest at heart? The response of Tourism Minister Martin Ferguson, that Tourism Australia has been cognisant all along of Mr Dixon’s interests in Qantas, is more confession than defense.

It’s not easy to tell if these examples represent a worsening of business probity in Australia. After all, a thin grey line between public and private benefits is certainly not new. In the lead up to the GFC there was a remarkable dissolution of boundaries between investment banking and former public servants as privatisation passed assets from public to private hands. Accompanying that reform, an open-door policy developed between senior public and private executive roles.

There is also the role of globalisation to consider. As Sell on News has described, American historian Philip Bobbitt sees three models for capitalism emerging in the form of market states: laissez faire (America), managerial (Europe) and mercantile (Japan). These three types will contest, just as communism, democracy and fascism contested for control of the nation state. Democracy, by the way, will struggle in the market state because its organising principle is one dollar, one unit of power, not one voter, one unit of power. As countries become more beholden to flighty international capital, it may be that the pressure upon governments to do special deals is growing. And in a post-GFC context of demand deficit, there is a global push towards closer integration between big businesses and governments that protect them, with all of the ‘behind closed doors’ connections that that entails. This might give you the sense that, for the time being at least, the Eastern market state which privileges connections (especially filial) over transparency and meritorcracy, is in the ascendancy.

But Australian capitalism is, at the best of times, a boys club. I don’t mean that as a comment about gender but rather an assessment of how the culture of Australian business works. It is, much like a footy or cricket team, a gang of mates. Often times, deals get done by pulling favours, regulators move against businesses behind the scenes, most sectors are so concentrated that success is often a case of trading assets between friends and, more to the point for this discussion, accountability in both the public and private sphere’s of our version of the market state is administered with such delicacy that punishment more often than not looks like reward.

This is not without its benefits. Familiarity makes crises more manageable and solutions more swift in the finding. But it also comes with problems. Anyone familiar with Paul Kelly’s seminal work, The End of Certainty, will understand that liberal capitalism is only lightly tolerated in Australian society. The default position for the nation is a noncompetitive, oligarchic business structure that unites big business and government in a productivity-killing partnership that perennially erode’s the nation’s standards of living. Who could deny such an undercurrent when the past few years has re-established an untouchable banking oligopoly with few offsets for the public, a clique of big miners that write their own tax rates and a car manufacturing sector on public life-support (that I agree with, to risk your wrath!) but for some reason must be kept secret.

If you want to have a functional liberal capitalist system, one that lays claim to the benefits generated by individual genius, innovation (and occasional pushing back of boundaries) then you must also lay claim to individual responsibility when things get cocked up. As FOMC member, Thomas Hoenig put it:

…a capitalistic economy – if you really believe in its long-term benefits – has cycles. People do make mistakes. See, the market is valuable not because it’s the smartest in the world, but because it’s the harshest. It captures mistakes and punishes and forces a correction. It’s when you then interfere with that that you allow the path to go off longer and the correction to be more severe and harder on people. And that’s what you can’t lose sight of when you say you’re for Capitalism, but not really.

* * *

Lambert here. But would Dostoyevski agree?

Another country but:

http://www.broadsheet.ie/2011/09/15/you-probably-wonder-from-time-to-time-why-this-guy-seems-untouchable/

“I don’t mean to sound condescending, but being in a country so much further along in this ugly process, there’s an underlying trust in authorities and process evident in this piece, while those sentiments are in tatters in the US.”

Oh, I don’t know. Liberals are only now, just barely, coming to the conclusion that the government is not going to fix what ails the US, whereas we probably are well past the point where that could have happened, (ie., Dan Kervick is right that his generation is the lamest).

Maybe if Australia wakes up a little quicker they can attempt a save.

Reading the article, I was struck by how small the examples raised were, by comparison to what we see here.

Is Mr. Market a nihilist? Why or why not?

Friends;

I’m not so sure the present socio political system can be saved. If you work from the assumption that governments serve with the assent of the governed, positively or negatively expressed, then the groundswells of ‘righteous anger,’ think the Chinese Boxer Rebellion, building up in, for want of a better word, the lumpen proletariat, will, if unchecked, bring the entire edifice down around our ears. It doesn’t really matter if the motivating principles are ‘Right’ or ‘Left,’ the end result will be the same; chaos, from out of which will emerge the next World Age.

The sub title of Mz Smiths book says it well: “How UNENLIGHTENED Self Interest Undermined Democracy and Corrupted Capitalism.”

I’m sorry to say that Canada is following in the US and Australian footsteps. We have “The Thieves of Bay Street” to thank for much of the corruption in the marketplace. That’s a book by Bruce Livesey and the review here covers its subject matter ( http://arts.nationalpost.com/2012/05/18/book-review-thieves-of-bay-street-by-bruce-livesey/ ).

Recently, the PM finally confessed that the banks in Canada were bailed out to the tune of $114 billion (more per capita than TARP). He refused to admit the money was a bailout calling it “liquidity support.” Well, when government gives money to banks because they will fail otherwise, that is a bailout. ( See: http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2012/04/Big%20Banks%20Big%20Secret.pdf )

Our government is in austerity mode (cutting 10% from public services and 19,000 public service workers) and is planning some great privatizations in the future. Woe, woe woe!

We have to admit that corruption is a world-wide phenomenon because all the big banks and corporations are intermingled.

On my worst days, I believe that capitalism has run its natural course and I wonder what will follow.

Struck by two things. First is “the default position for the nation is a noncompetitive, oligarchic business structure that unites big business and government in a productivity-killing partnership that perennially erode’s the nation’s standards of living.”

I agree on the oligarchy bit (just as in other smallish countries, there just is not room for several competing centres of business and finance). But perennially eroding the nation’s standards of living? The ordinary standard of living in Australia is – and pretty much always has been – higher than in the US. Yes, notional per capita income is lower – but it’s more equally distributed, and non-income benefits like healthcare and education are much higher. Australia is in semi-permanent panic about its prospects, and has a deep inferiority complex, but these are self-inflicted neuroses, not facts (“aagh, we don’t all live like millionaires, like they do in America as seen on TV!!!).

Second is that Australia has always had a fairly shonky business sector, right from the days of the Rum Corps. We just relied on the bureaucrats (not the judges – they were usually part of the scene) to keep them in line. This does seem to have eroded a bit over the last couple of decades.

Yves,

Thanks for getting the word “chthonic” into the finance blogosphere (where it indubitably belongs…) Just another of the innumerable ways in which you keep NC at the top. The hand transformation image hit the spot, too…