This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1147 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, bonuses for our esteemed writers.

Charles Darwin’s enduring legacy rests not only on his discovery of natural selection, but also on the extraordinary breadth of its explanatory power. Evolutionary theory is applicable to all manner of systems from biology to behavior, and now, the technology of war. Today, the evolutionary logic of adaptation and survival is playing out in drone warfare.

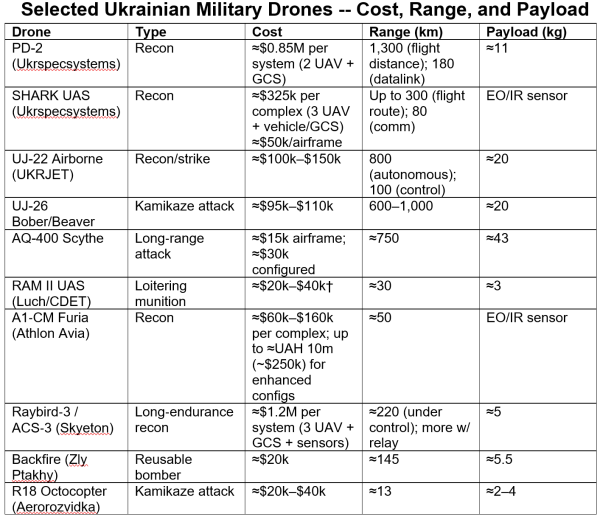

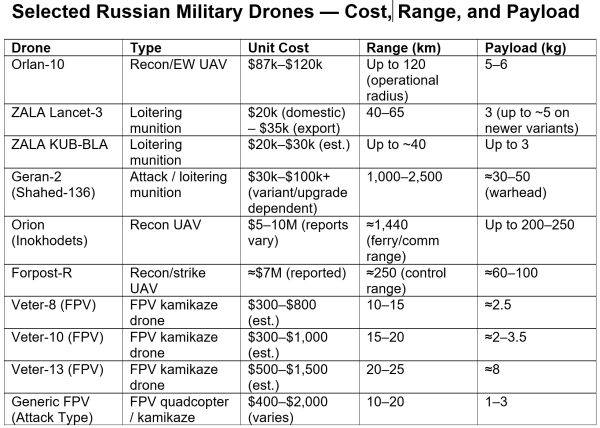

The war in Ukraine has become the first full-scale conflict in which drones dominate every zone of combat, from trench lines to strategic deep strikes. What began as a desperate improvisation with civilian quadcopters has transformed into a relentless contest of innovation, countermeasures, and counter-countermeasures. Each new adaptation on the battlefield triggers a quick technological response, greatly reducing the gap between research and deployment.

This rapid evolution has turned Ukraine into the world’s most dynamic military drone laboratory. The conflict now demonstrates that airpower is no longer the exclusive province of state air forces. Instead, a distributed ecosystem of relatively inexpensive, software-driven systems can achieve effects once reserved for costly precision-guided missiles and manned strike aircraft. Understanding how this transformation unfolded offers critical lessons for militaries worldwide.

Improvised Beginnings

In the chaotic opening months of 2022, Ukraine faced a numerically superior invader. Its early edge came not from high-end Western platforms, but from consumer drones bought off the shelf. Civilian quadcopters like the DJI Mavic, costing under $2,000, were repurposed to spot artillery targets and adjust fire in real time. Soon these drones were modified to deliver munitions, making them precision-guided weapons.

Weaponized drone – small but deadly

Grassroots networks of volunteers, tech hobbyists, and veterans formed ad hoc units such as Aerorozvidka, pioneering battlefield hacks: 3D-printed bomb racks, modified GoPro cameras, extended-life batteries. These innovations converted hobby drones into lethal spotters and light bombers. The effect was immediate: artillery accuracy improved, small units gained real-time intelligence, and morale surged as soldiers saw their own strikes broadcast live.

Russia, relying on traditional reconnaissance and centralized command structures, was initially slow to adapt. The early months thus marked a paradigm shift: drone improvisation delivered an artillery multiplier and direct attack weapons. A new arms race had begun.

Industrialization and Swarming

By mid-2023, improvisation gave way to industrialization. Both sides recognized drones as indispensable, and domestic production lines emerged to meet insatiable battlefield demand. The First Person View (FPV) revolution, repurposing high-speed racing drones into precision-guided loitering munitions, transformed tactics. Pilots, wearing video goggles, steered drones directly into enemy armor or fortifications, achieving precision strikes at a fraction of the cost of guided missiles.

FPV drone operator – a view to a kill

Ukraine’s decentralized model encouraged rapid iteration: components sourced globally, assembled locally, and tested within days. Russia responded with mass production of its own FPV systems and dedicated electronic warfare (EW) units. This set off a new electronic duel — with jamming, frequency hopping, and anti-jamming technologies evolving in near-real-time.

The result was a shift from occasional drone use to persistent aerial presence. Every trench, armored column, and supply route now operated under constant observation. The swarm had arrived, and with it, a new definition of air superiority measured in volume and duration of battlefield coverage.

Strategic Deep Strikes

As capabilities matured, the battlespace expanded. Ukraine began launching long-range drones deep into Russian territory, striking oil depots, airbases, and even the outskirts of Moscow. Many of these systems combined legacy Soviet engines with modern guidance — a fusion of old hardware and new software.

These attacks were not merely tactical disruptions; they carried profound psychological and strategic effects. Russia, which once enjoyed sanctuary in its heartland, now faced nightly alerts and scrambled interceptors. The cost-exchange ratio favored Ukraine: a drone worth tens of thousands forced the diversion of million-dollar air defenses and civilian anxiety in major cities.

Moscow adapted with dense radar coverage and layered SAM networks, yet no defense can guarantee immunity from low-observable, expendable threats. The drone had erased the boundary between front and rear, turning the entire theater into a contested zone.

The Techno-Operational Feedback Loop

Perhaps the most striking feature of the drone war is its compressed innovation cycle. In traditional procurement, weapon systems evolve over years; in Ukraine, weeks suffice. Every tactical success triggers imitation and countermeasure. A new FPV mount appears on Telegram today; by next week, adversaries are testing defenses.

This constant experimentation mirrors a Darwinian process of selection: designs that succeed under fire propagate instantly across the front, while ineffective models vanish from production lines. Crowdsourced R&D blurs the line between soldier and engineer. Volunteer collectives fund projects, share code, and publish field results openly.

A vivid illustration is the rapid adoption of fiber-optic guidance in frontline FPV systems. As electronic jamming intensified, degrading radio-controlled drone links, Ukrainian and Russian engineers independently revived the concept of tethered control over a fiber optic cable, drawing inspiration from anti-tank missiles like the 9K135 Kornet. Within months, drones equipped with spooled micro-cable guidance appeared in combat, immune to radio interference and capable of precision strikes in heavily jammed zones. Though the added weight and limited range impose trade-offs, the innovation demonstrates the agility of combatants to iterate under pressure, substituting one evolutionary constraint (mobility) for another (resilience). Each adaptation feeds back into the next design cycle, refining the balance between connectivity, survivability, and lethality.

Fiber optic drone – jam-proof guidance

Artificial intelligence increasingly enters the evolutionary process. AI software for targeting, automated navigation, and swarm coordination is in active development and is being deployed. This battlefield natural selection rewards adaptability over pedigree. Survival depends less on industrial scale than on the agility to reconfigure tools faster than the opponent. It is warfare at startup speed — iterative, experimental, and unforgiving.

🇷🇺💥🇺🇦

BREAKING NEWS !!!

Russian “Gerani” have started hitting moving targets

▪️In the Chernihov region, for the first time, a strike was recorded on a Ukrainian railway echelon carrying fuel while it was moving 150-200 km from the border.

The new drone model is equipped… pic.twitter.com/gIhSX0qNfl

— 𝐃𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐝 𝐙 🇷🇺 🇷🇺 (@SMO_VZ) October 1, 2025

The Evolution of the Shahed-Type Drone

In parallel with the tactical FPV explosion, a separate evolutionary branch of Russian drones emerged, based on the Iranian Shahed family of long-range drones. These propeller-driven, delta-wing, loitering munitions were conceived for affordability and range rather than precision. Introduced into the Ukraine war in late 2022, they represented the first mass-produced strategic drone species, optimized for long endurance, minimal radar cross-section, and saturation attacks.

Early Shahed variants exhibited crude navigation and limited accuracy, but successive Russian iterations, notably the Geran-2 versions, incorporated improved guidance, GLONASS satellite navigation modules, and domestically sourced components to bypass sanctions. Over time, adaptations enhanced reliability, fuel efficiency, and warhead stability, making the Geran an increasingly fit organism in the Darwinian ecosystem of long-range warfare.

This drone’s value lies less in sophistication than in niche dominance: it can travel hundreds of kilometers, evade some air defenses through low-altitude routing, and force defenders to expend costly interceptors. A single Patriot interceptor costs about $4 million, whereas the cost of a Geran strike drone is estimated at $40k–$200k. The exchange ratio therefore favors saturation tactics imposing significant asymmetric costs on Ukraine.

As production shifted to Russian soil, the Shahed’s evolution accelerated. Domestic assembly lines now produce hybrid models blending Iranian airframes with Russian avionics and engines, forming a localized subspecies, the Geran, suited to the Eurasian theater. Deployed in waves, these drones overwhelm defenses through numerical superiority, a survival strategy based on replication rather than innovation. There are reports of new Russian Gerans that are jet-powered, doubling speed and increasing the difficulty of interception.

In biological terms, the Shahed/Geran lineage exemplifies stabilizing selection: a design refined not by radical mutation but by iterative optimization within a specific environment, the long-range strike domain. Its persistence underscores a key truth of drone warfare: evolutionary success requires not only novelty, but reproducible sufficiency.

Russia’s Drone Manufacturing Capacity

While Ukraine has excelled in innovation and agility, Russia has exploited its industrial depth and centralized production efficiency to seize an advantage in drone manufacturing. By late 2024, multiple Ukrainian and Western sources claimed that Russian output of FPV and reconnaissance drones exceeded 100,000 units per month, although these estimates are contested. The broader picture is clear even amid uncertainty: Russia has emphasized standardization, volume, and resilient supply chains, while Ukraine has excelled at rapid, field-driven innovation. One model prioritizes continuity at scale; the other prioritizes agility. Matching Russia’s throughput would require coordinated production, hardened supply lines, and shared standards across Ukraine’s partners.

This scaling capacity reflects an evolutionary bifurcation: Ukraine’s ecosystem thrives on rapid experimentation and field-driven adaptation, while Russia’s model emphasizes standardization, volume, and logistical resilience. The former favors novelty; the latter ensures continuity. As a result, Russia now fields a steady and growing supply of uniform, interoperable drones, a critical asset in sustained attrition warfare.

Geran drone production – quantity matters

This industrial edge may prove decisive in a prolonged conflict. In evolutionary terms, Russia’s advantage lies not in variation, but in reproductive fitness: the ability to replicate successful designs faster and at greater scale than the adversary. For Ukraine and its Western supporters, matching this capacity would require coordinated production, supply-chain resilience, and shared technical standards, a challenging industrial mobilization of innovation.

Ukraine’s war effort is highly reliant on energy and rail transport infrastructure. These are elaborate networked facilities, highly resistant to scattered strikes, but with extensive long-range drone attacks, Russia may be able to cripple the Ukrainian energy and rail systems. Estimates put the current output of Russian Geran drones at around 100 a day. In Ukraine, there are roughly 90 330 kV electricity distribution substations, which are the energy supply backbone of the electrified rail network, and there are approximately 500 to 1,000 diesel locomotives. Recent numerous Russian drone strikes on energy infrastructure and trains suggest that a tipping point may be near, with ominous consequences for Ukraine.

Countermeasures?

Despite extensive efforts to devise effective countermeasures against attack drones, the drones have the upper hand. Electronic jamming is only partially effective against radio controlled drones and useless against fiber optic guidance. Vehicles with protective screens or cages may stop a single strike but will not survive multiple drone hits. Guns can’t reach drones at high altitude, and interceptor missiles are too expensive to use in large numbers. Anti-drone drones have had some success, but their interception envelope is limited. Drone evolution has simply outpaced the technical capabilities of defensive systems, and there are no near-term remedies in sight. Defensive innovation is lagging; unless radically accelerated, the imbalance will persist.

Anti-drone cage – no guarantee of survival

Strategic and Doctrinal Implications

The proliferation of cheap, effective drones undermines long-standing assumptions about force structure. Cost asymmetry has become decisive: a $500 FPV drone can disable a $10 million tank. Traditional metrics of military power, tonnage, armor thickness, sortie rate, lose relevance when quantity and expendability outweigh mass. Moreover, an unfavorable cost exchange ratio against interceptor missiles places a further burden on defenders.

Persistent aerial surveillance erodes concealment, rendering static defenses and troop concentrations hazardous. The old doctrine of maneuver under cover is obsolete in skies saturated with loitering sensors. Armies must now disperse, camouflage electronically, and expect continuous observation. Psychologically, the overhead buzz of drones has reshaped infantry experience, inducing fatigue and hypervigilance. Meanwhile, the democratization of airpower decentralizes control, empowering small units while complicating battle management.

Doctrinally, this represents not just technological adaptation but evolutionary divergence: forces that fail to adjust face extinction on a battlefield where iteration is survival. For major powers, the message is clear: future combined-arms operations must integrate drone defense as thoroughly as armor or artillery. Air superiority will depend as much on jamming and counter-UAS tactics as on fighter jets.

Global Lessons and Policy Outlook

The lessons of Ukraine are already global. Taiwan studies FPV tactics for coastal defense; Israel integrates micro-drones into urban operations; Iran refines exportable loitering munitions. NATO militaries, once skeptical of non-traditional platforms, now race to replicate Ukraine’s innovation pipelines. Yet ethical and legal frameworks lag far behind. Civilian infrastructure and urban centers increasingly fall within drone range, raising questions of proportionality and accountability. The dual-use nature of components, from lithium batteries to GPS modules, complicates export controls and sanctions.

For major powers, industrial policy must pivot toward micro-production ecosystems emphasizing software, autonomy, and rapid iteration. Nations with both strong technology capabilities and mass manufacturing resources will have advantages in large-scale conflicts, but drone technology also enables asymmetric warfare by smaller nations and non-state actors. Proliferation of drone weaponry is already taking place, and this may lead to growing instability in conflict regions worldwide.

Conclusion

In less than three years of the Ukraine war, drones have evolved from aerial scouts to potent strike systems. The transformation reveals more than technological ingenuity; it signals a structural shift in warfare itself. The conflict demonstrates that adaptation is the critical success factor. Survivability and effectiveness derive not from thickness of steel or caliber of shell, but from speed of innovation. Like organisms in a hostile ecosystem, drone systems that fail to evolve perish swiftly, while those best suited to the environment propagate across the front. As nations absorb these lessons, the war in Ukraine foretells the drone warfare of the future: dense, autonomous, and in constant flux. Aerial supremacy no longer belongs to conventional manned air forces. In the drone-saturated battles of tomorrow, victory will belong not to the strongest, but to the swiftest to evolve.

Regarding the technological ingenuity of drones, I’ve been wondering why someone has developed an even cheaper countermeasure, namely, a net. But I just checked and apparently it’s been done, at least on a small scale – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=68-S4Xy09SE Seems like an effective way to counteract swarms, depending on how close together the drones are flying. Instead of the hand launched net shown in the video, netting could be flown above a drone swarm and then dropped on top of it. Maybe even use small drones to pull the netting to the appropriate circumference before dropping it on a swarm.

Anti-drone nets are used extensively to cover important roads in Ukraine, but any gap becomes an entry point for drones. Also, conventional bombs and artillery can tear up the nets, making holes that drones can fly through. Thousands of smart people on both sides of this war have been working on drone countermeasures, so far without much success. There is also a classic offense/defense asymmetry. The defense has to be effective everywhere, but the offense can concentrate attacks anywhere.

So far I’m reading that offense is the best defense: Russians now have units dedicated to hunting down Ukrainian drone operators. Reconnaissance drones, signal intelligence, ground observers all trying to pinpoint the Ukrainian operators and feeding data to both long range artillery and loitering Russian drones.

It’s been claimed that a Ukrainian drone operator has a life expectancy of less than 6 months at the moment.

Ukrainians claim that this is how they know Russians are preparing for a ground operation: in a few weeks they lose all their drone operator teams in a certain area and the next thing you know is the Russian motocross troops all over the place.

Another ecological analogy – if an innovation dies with the drone operator, it’s like a novel adaptive gene that does not reproduce and is lost to the species gene pool. A short life expectancy means more “reproductive failures.”

It is indeed. And no, this:

Is not the solution.

The primary goal should be to physically cut Ukraine off from NATO, then finish it off without it being supplied with drones. Or any other weapons.

That in fact had to be the SMO’s #1 priority from Day 1. But Putin sent pathetically few forces to try to take Nikolaev, which meant they never even made it past the Bug, let alone reach Odessa. And there was never any force even allocated to try to seal the Polish border. Only a small incursion towards Zhytomyr that went nowhere.

Defense needs to be broken down into area defense and self defense. Systems like Patriot are intended for area defense and as noted saturation tactics will defeat area defense.

So self defense becomes a key. It seems like passive measures are mainly being used aside from EW against comms up/down links. It isn’t clear if EW is employed against onboard sensors, or if decoys are deployed. Self defense hard kill systems with range in 100’s of meters seem an obvious option.

Excellent work. I learned quite a lot. I know it may be like giving away your secret source but can you say a little boutique how you’re sourcing this?

The Ukraine war is probably the most closely observed armed conflict in history. Aerial strikes and battlefield changes are reported multiple times every day, sometimes within minutes of the events. There is a huge amount of material in the public domain. It’s just a matter of collecting and analyzing it.

Thanks.

It’s just a matter of collecting and analyzing it.

Drinking from the fire hydrant, huh?

Bah. I meant secret sauce for secret source and a little bit not little boutique.

Goddam spellcheck altering what I wrote when I’m on a phone and didn’t catch it.

Due to the lack of effective countermeasures against drones, armored vehicles are rarely seen on the Ukrainian battlefield, regardless of which side they belong to. Ukrainian soldiers travel in ordinary pickup trucks without protective cages. Their only survival strategy is to jump out immediately if spotted by Russian drones.

As demonstrated in Ukraine, drones are highly effective. Had Hamas possessed kamikaze drones, the Israeli military would have suffered devastating losses. Yet, for some reason, no one ever supplied Hamas with drones.

I think this excellent overview misses a significant aspect regarding the early phase of the war.

Initially, the Ukrainians relied on the famous Turkish Bayraktar drone — to such an extent that they even composed an hymn to Bayraktar mocking the Russians.

That was not unexpected. The Bayraktar had provided the Azeri military a decisive edge against its Armenian foes during the second Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020, and was also instrumental in allowing Ethiopian troops to regain the upper hand after their initial reverses during the Tigray war, from 2021 onwards. It was natural that other armies, such as the Ukrainian military, acquired that model, since it seemed to be so effective.

The Bayraktar is quite large (6.5m length, wing span 12m), flies at medium altitudes (5.5-7.6km), at fairly low speeds (130-220km/h). Apparently, its speed was initially a problem for radars fine-tuned to track much faster aircraft.

To keep with the article’s argument of an evolution race, the Russians eventually figured out the weak spots of the Bayraktar and started shooting these drones down in significant numbers with their anti-aircraft weapons. The usage of the Bayraktar declined markedly in the second half of 2022, became episodic in 2023, and the Ukrainians basically stopped using it in summer 2023.

Without sounding too clueless… what would happen if there were thousands of individuals with laser pointers? It’s illegal to point them at planes, wouldn’t they be effective also in blinding or at least interrupting guidance/visual systems?

That’s not really a clueless question at all, but sort of a gateway to the entire field of Electronic Warfare / Electronic Countermeasures (EW / ECM) What you’re describing essentially exist already as “dazzlers”

There are 2 main catches that are arguably what make military EW / radar engineering both hard & secretive:

1. Any signal your platform actively sends out (including to disable an enemy) at least partly reveals your platform to enemy sensors.

2. Even if you can knock out one sensor for one band of radiation, the economy, signal range, & networkability of modern sensors are crazy. Physics still imposes certain limits (atmosphere will scatter very high-frequency radiation, very low-frequency signals have poor resolution in isolation, beam intensity & sweep are inescapable trade-offs, etc.)

But if you can get a sufficient sensor network in place (like the Russians seem close to in Ukraine), the synergies make losing a few sensors on the margins irrelevant. That’s partly why I tell people, though I think a lot of harm will come out of the current AI moment, AI doesn’t scare me. The words “sensor fusion” OTOH are something I would never want to be on the receiving end of.

I have seen suggestions that shotguns might be useful for point defense of infantry under attack by FPV drones.

Directed energy weapons. Not just lasers, but the microwave equivalent.

It falls under the umbrella term of “Electronic Warfare”, and another umbrella term used is “Electromagnetic Spectrum Operations” or EMSO. I’ve been following the developments via the EW professional organization, Association of Old Crows.

They have a podcast interview with a Croatian volunteer in Ukraine who is a drone pilot and engineer https://fromthecrowsnest.transistor.fm/episodes/this-is-where-i-should-be-inside-the-front-lines-of-ew-in-the-russo-ukrainian-war

I have been following drone iterations. The rapid progress has reminded me of WWI airplane progress. This is a great overview.

What we have been observing in Ukraine and Gaza are live fire arms fairs. It’s not only drones but surveillance tech and countermeasures which have rapidly advanced in capacity to threaten the everyperson. They are likely coming to a neighbourhood near you sometime soonish. What a way to settle the pettiest of disputes.

The advance in UAV/drone tech has mirrored the changing uses of aircraft during WW1 which commenced as forward observers for artillery, then hand dropping of bombs and on.

I was thinking the same. It has been said that WW1 accelerated aircraft development by about twenty years. The fragile ‘kites’ in use at the start of the war had little resemblance to the highly sophisticated machines in use by 1918. But drones are different in that they do not need industrial aircraft manufacturers to make them. I have noticed some smaller countries in Africa adopting them due to their effectiveness. For major armies, military action is going to get a lot more complicated if drones are part of the picture. Imagine if Trump goes ahead with his invasion of Venezuela – only to discover that the Venezuelan military has quite a stock of drones on hand. And those drones are wrecking US aircraft and helicopters on those seized airfields. Would the US military be ready to deal with the threat that the Russians and Ukrainians have to deal with each and every day?

There is currently only one solution to the drone scourge — deprive the enemy of them.

Which Russia has the tools to do, but Putin refuses to use them.

In this case this means the Polish and Romanian borders have to be shut completely by force or the threat of using the kind of force that would compel Poland and Romania to comply. Hungary and Slovakia presumably will be much more cooperative.

There is no other solution.

And in case anyone hasn’t gotten the hint, yes, that means the nukes come out.

The alternative is the war remaining a stalemate for decades. This, combined with the absurdity of agreeing on the current arrangement, which is that NATO can strike deep inside Russia but Russia is not allowed to strike back even once, guarantees a Russian strategic defeat.

gm: in case anyone hasn’t gotten the hint, yes, that means the nukes come out.

What are the Oreshniks for?

Because I fail to see why those won’t do the job. Putin explicitly said as much after the first one was used.

The alternative is the war remaining a stalemate for decades.

The neoliberal states of the West and of the EU/NATO specifically will not have the capability to maintain a war for decades. France is wobbling on the verge of financial collapse, Germany’s industrial contraction continues to 2005 levels as of today, and while the UK may teeter on as it did in 1848 when unrest broke out all over the continent, its main interest in the Ukraine war was seeing the EU reduced and divided and that will have been accomplished.

What exactly is an MRBM with 3-4 tons throw weight going to achieve if it does not carry nukes?

Ukraine receives a combined throw weight of 50-100 tons of explosives sent its way+- every single day, what has that achieved?

The Oreshnik only makes sense as a nuclear delivery system. And almost certainly that is what it is, it’s just that Putin is still in appeasement mode so he could not say it when he publicly talked abot the Oreshnik.

Oreshniks are a replacement for tactical nukes in some use cases, especially targeting hardened underground bunkers. It means no leader in Europe can retreat to a bunker and feel safe – they could be targeted without needing to start a nuclear war.

Oreshniks make no sense as nuke delivery system. Russians already have various other missiles meant for that. Oreshniks allow

them to escalate without going nuclear.

And you underestimate russian patience. They are breaking apart Nato, building a massive military capability and profitable export sector, and forging new alliances left and right, and a very strong alliance with the new most powerful nation on Earth, China. They are displacing a hegemon without falling into the thucydides trap so far (ie all out war with the US).

If you think they’re appeasing, you totally misread the situation.

????

You have absolutely no idea what you are talking about.

Nobody has ever fielded a missile of that size that was anything but nuclear.

Because these missiles are very expensive and if they are not nuclear, they just don’t make any sense.

And no, Russians had no other such missiles. The INF treaty made sure about it, and then NATO started taking care of their long-range ALCMs through Operation Spiderweb and the other one-off drones strikes on the strategic aviation, but ALCMs are too slow for the kind of strikes that are needed anyway.

You underestimate what traitors the Russian elites are. The nuclear threshold was passed long ago. Long, long, long ago. We are way way way past the point where it was not just warranted, it was mandatory to smoke out all of Europe and every single US base in Eurasia and then dare the US to initiate an all-out exchange or back off.

But Putin hasn’t fired a single shot back, because his primary role is to serve the Russian oligarchy, and the Russian oligarchy wants to go back “how things were”, not to fight the GPW again. After all, the scumbags who broke up the USSR in order to loot its riches are still the core of the Russian elite. There has been no purge whatsoever.

How? Finland and Sweden joined, the other countries are under stricter US control than ever, Moldova was captured, Armenia and Azerbaijan too, etc. etc.

There is a tendency to assume that dragging the war out to the last Ukrainian is now the primary European aim. It may also serve Russian interests to keep the conflict slowly moving along until more European governments fall, and the fragments of the EU and NATO are blown to the wind. Russia will be the dominant power in Europe and can start to shape it to its ends, ensuring that the major European countries are effectively de-militarised for the next fifty years or so.

Good to see that the lunatic warmongers that would get us all killed also exist on the pro-russian side…

He is not on the pro-Russian side.

This post, https://nitter.poast.org/RWApodcast/status/1975482041786597784#m, talks about how the battlefield is now made up of tiny groups (2-4 soldiers), that have to walk many kms to the frontline because they can’t get transport any closer. Routes and Lines of Communications are regularly mined, so getting resupplied is fraught with danger. With infrared sensors, nighttime is more hazardous: “If you haven’t found your fighting position before sunset — you die.”

It explains why there is so little movement on the frontline – it is impossible to bring a large force together to push through one point.

If the war goes on much longer, I can foresee AI playing a much larger role. FPV drones are very effective but obviously are limited since a person has to fly the drone. If flight and targeting can be delegated to AI, then Russia with its greater manufacturing capability will likely force a complete win. OTOH running an AI program requires a fair bit of compute power and energy, which will impact how far and how long a drone can be airborne. Also, the AI itself could become a target for hackers.

Greater manufacturing of what? Drones? The drones come from China, for both sides.

So the side with the deeper pockets will win, and that is not Russia. Unless the Chinese finally wake up out of their arrogance slumber and realize they are next on the menu and that their fancy weapons will not save them when they are surrounded from all sides.

From the OP:

“While Ukraine has excelled in innovation and agility, Russia has exploited its industrial depth and centralized production efficiency to seize an advantage in drone manufacturing.”

This is the usual confusion between large one-way attack drones used for deep strikes and the small off-the-shelf drones that have stalemated the battlefield.

The side with deeper pockets may well win, but that isn’t going to be the US or the Europeans. Life can become very difficult very quickly for debtor nations.

Agree that the conflict has seen rapid development of drone weapons and tactics. Think you may underestimate the strategic impact in Ukraine of RF dominance in long range strike weapons, electronic warfare, and air defenses. FAB 500 glide bombs for example are responsible for much destruction of entrenched positions, and their use accelerated with the destruction of Ukrainian air defenses.

Personally I think the fact that much of Ukraine is still intact says less about RF capabilities and more about their understanding of the rules of engagement in a special military operation vs. a war. And I believe Ukraine’s increasing reliance on drones says less about (genuine) Ukranian ingenuity and more about the destruction of their other weapon systems and loss of manpower.

Actually the drones have reduced the effectiveness of FABs too, by forcing the total atomization of the enemy forces.

UMPK FABs are very useful for blowing up fortifications, and if those fortifications hold a dozen or more enemy soldiers, that destroy the enemy forces very fast.

But if you have one or two soldiers holed up in dugouts that aren’t even visible, then FABs are much less effective.

Pay attention to how the war developed. UMPKs appeared first in early 2023 and then played a major role in the break through in Avdeevka, which happened in late 2023 and early 2024. Avdeevka was extremely fortified, having been the base for terrorizing Donetsk for a decade, and it was only thanks to the UMPKs (and the pipeline operation) that it was taken. And around that time there was a palpable acceleration of the war — it went from basically no Russian advances to more than 5 km^2 a day, which was a huge jump.

But now we are at Pokrovsk and serious attempts to take it have lasted much longer than the Avdeevka operation. Even though Pokrovsk in in fact not really heavily fortified in the way Avdeevka was at all. Because what happened was that last year around that time it very much looked like Russia has found to the key to rapidly breaking Ukrainian resistance because a string of actual cities, even though not very big (not the usual random villages with pre-war population in the low hundreds) fell in rapid succession — Vugledar (which had been another major fortress), Krasnogorovka, New York, Dzerzhinsk, Ukrainsk, Gornyak, Selidovo, Novogrodovka, Kurakhovo, Velika Novoselka, all of those fell between August 2024 and January 2025. And then the Russian army ran into the drone buzzsaw south of Pokrovsk, where it was impossible to move any further because of the drones.

Same situation developed around Volchansk already in May-June 2024, and later on when Russia tried to enter Sumy coming out of Kursk. And those places were not really fortified at all.

The result is that Russia is yet to take a city in all of 2025 so far, and the only place where there is a steady rate of advance is along the border between the Zaporozhye and Dneproptrovsk regions, where the most skilled units operate. There they have moved 70-80 kilometers in the last 9 months. But elsewhere it has been near impossible to move. Despite the UMPKs, for the reasons I explained above.

Now we are talking.

A lot of people are taking the absolutely wrong lessons from this war — a serious war will not be fought with drones in trenches. Not that this is isn’t a serious war — this is as existential for Russia as the GPW was — but the Kremlin refuses to take it seriously to this day.

In a real war fought with no restraints by both sides, strategic weapons will be deployed to destroy the other side’s capacity to wage war and there will not be a line of contact. It will look much more like the missile/air strike exchange between Iran and Israel.

Also, a minor nitpick with Haig’s characterization of Russian force as having been numerically superior: they were not. I remember tearing my hair out trying to find ways to come up with the kind of numbers of troops they supposedly launched the invasion with. As it were, I think it’s broadly accepted that the Russian force was only around 120-150 thousand strong and relied on boldness and speed (and paid for the latter as their positions inside Ukraine were not very defensible, due to many key bastions remaining in Ukrainian hands that complicated possible Russian defenses). The extent to which Ukrainians succeeded in their defenses, with drones or otherwise, is rather overplayed, methinks.

Not minor at all. Numerically inferior force managed to capture large swaths of land in short time. That means that defences were crap, drones or not. After they overstretched, they had to retreat. Early mobilization gave the edge to Ukrainian forces.

A minor nitpick would be laser beam riding Kornet credited as inspiration for fiber optic guidance. :)

One should also keep in mind that around 80-100 thousand of those “Russian” troops were actually mobilized separatists “Ukrainians” from Donbass.

As the Ukrainian shelling at the time was intensifying and Ukrainians were creating pathways trough the minefields, on 19th February both Luhansk and Donetsk mobilized and began evacuating children (the horror!) and other dependents to Russia.

I personally remember drones becoming a serious subject sometimes around battle of Bakhmut. For example, a documentary of the battle of Mariupol does not mention or show drones at all.

Yes, indeed, Mariupol was classical warfare. And Russia did rather well.

Had that window of opportunity not been missed, we would be in a very different world now.

But Putin refused to prepare for the war (they were bragging in the years between 2014 and 2022 how little they spend on the military), went in forcing his own army to go in under absurd self-restraining rules meaning it was fighting with one and a half hands tied behind its back, then refused to mobilized in March 2022, and all the way to September 2022, and even then didn’t mobilized properly, and still hasn’t.

This is my turf.

Familiarize yourself with Ondas and Wrap Technologies– leading USA anti-drone systems. This video is important:

https://vimeo.com/1118106520

Yes, nets and wraps are huge as non-destructive means of taking-down drones. The two companies I’ve cited are launching bigly into DoW and other agency anti-drone efforts.

November 24 is when DoW (Department of War) announces winners if this year’s anti-drone competition.

LD, I’d be interested in your thoughts on Anduril’s combo of AI/software (Lattice) and kinetic (Roadrunner) counter-drone tech.

These systems definately arouse my curiosity.

The “Iron Drone” by Ondas and Wrap’s bolo devices are basically non-destructive designs that reduce risk of civilian casualties, so could be used for law enforcement purposes as well as on (above) the battlefield. Anduril appears to be pure war-fighting, and with AI (as with fiber-optic), there’s practically no vulnerability to signal disruptions/EW. The “drone-in-a-box” design utilized by Roadrunner has become a more common feature or method of deploying drones,

such as civilian package delivery drones– makes set-up a breeze.

The Roadrunner looks like an answer to large-scale drones like Shahed, whereas the former could target small to mid-sized ones efficiently and cost-effectively. Networked, AI could decide what type of counter-drone systems to deploy once a threat has been detected and identified.

We sure aren’t living in 2022 anymore.

Appreciate the reply, thank you.

We sure aren’t living in 2022 anymore.

Indeed!

Modular entanglement cassette is my entry in this decade’s military buzzword competition.

Seems like a promising idea, but these guys need a way better marketing video. I can’t understand how the product works or discern a good example of what it does here.

Here’s the modular entanglement cassette of my youth:

image

To elaborate slightly, there is no single tool for drone defense– you’re looking at layers of anti-drone systems, from microwave, SAMs, shotguns, lasers, EW, etc..

It’s toatally cat-and-mouse– on meth. No exaggeration that things are changing week-to-week.

I wonder if this is true unconditionally. A major factor behind proliferation of drones is, after all, access to cheap and reasonably capable microelectronic devices, of which China is the key source. Can any country do this while antagonizing China, or even against China? There are some places that can supply microelectronics in quantity–Taiwan is likely one of them–for some time. But Taiwanese industry has gotten so integrated with that of the mainland that I’d be skeptical that they could operate independent of the mainland for long.

Great piece, HH.

It strikes me that much of Western contempt for Russia’s limited advances comes from a complete failure to understand how much drones have changed the game.

The article is filled with Western misconceptions from the very beginning. Russia has never had any numerical advantage at the front. No Ukrainian drones reach the outskirts of Moscow, and no one in Moscow is afraid of them. All Ukrainian drones are shot down on approach to Moscow, and far from the city. Recently, Ukrainians have even reduced their number and are looking for other targets somewhere in sparsely populated areas.

Oh, yes, they do, and much further.

What do you think blew up the refineries in Bashkiria?

Drones have reached Bashkiria, but they don’t reach Moscow. There is already a dense air defense network near Moscow. It won’t take long for Bashkiria to have a lot of air defense. All these Ukrainian drones fly low and slowly. Even a Kalashnikov assault rifle can handle them.

If the aiming problem can be solved (!!!), a rifle seems like an excellent anti-drone weapon. It’s portable, ubiquitous, and the cost per shot is under a dollar. We already have giant factories cranking out ammunition in mind-numbing amounts and no one is predicting any shortage or multi-year backlog of bullets.

Maybe the venerable .50 calibre machine gun can be repurposed for this. The a rate of fire is high and the shots reportedly go for miles.

Drones are already being shot down with large-caliber sniper rifles equipped with a thermal imager. Thus, many agro drones were shot down, which the Ukrainians are converting into bombers. They lift and carry an anti-tank mine.

But they can also be shot down with a Kalashnikov assault rifle. Cartridges with large buckshot. In three seconds, 90 metal balls fly out of the machine gun at an aiming distance of up to 400 meters. If you have three people, they will fire over 800 of these bullets in 15 seconds. Taking into account the recharge. Getting into a flying drone is not difficult.

Good luck downing an An-196 with a rifle.

In addition to rifles, there are large-caliber anti-aircraft machine guns and even 100-mm anti-aircraft guns) There are many different air defense systems. There will be no problems with destroying this ancient aircraft. Such planes are constantly being shot down in Russia.

Yes, they do reach Moscow.

This is from September 28:

https://t.me/RVvoenkor/100678

I am sure that woman and her grandson and their relatives are immensely thankful for the reliable protection that Putin has provided them.

There is no such thing as perfect air defense. If you keep just taking it, you will get hit. It’s that simple.

The purpose of air defense is to absorb an initial attack and to protect as much as possible while the enemy is beaten back and defeated. But in the case of countries like Russia (and the US), the assumption has always been that the first attack will also be the last. Because it would be followed with the immediate destruction of whoever attacked.

But when the destruction of whoever has attacked is not even on the table as an objective, not even that, but the people responsible are very carefully protected by the Russian leadership, well, then you get the s**t show that we have been in for three years now.

Voskresensk is located 70 km from Moscow. Grandma and grandson are not military, but civilians. Ukraine is engaged in terrorism.

Which could be terminated very quickly by, you know, punishing the terrorists.

But the terrorists have not been touched for 12 years now, while Russian patriots critical of the Kremlin for refusing to fight seriously are in jail.

Which is rather telling, isn’t it?

Drones from Finland, or from within Bashkortostan itself which has a pretty small Ukrainian population and a small independence movement.

I predict within 5 years (in 2030) drones will be used by governments to track the movement of protestors as they leave their house on the way to an event. The drone will automatically alert your bank that you are a participant in an unauthorized protest event and your account will be frozen, then likely seized. As you approach the protest point, you will be sprayed with either pepper spray or indelible ink to be easily spotted and picked up by the goon squad. First it was teflon, created by the space program and next “control drones” created in the fields of Ukraine and Russia. Thanks a million, “progress”.

My guess is that this is going to be the greatest impact of the introduction of drones onto the battlefield. Traditional militaries have relied on massed troops, stationary bases and airfields, and large weapon systems like tanks and ships. In a current war environment these are nothing but big fat targets asking to be blown up; however, most military doctrine, strategy, and procurement is based around these kinds of things.

The Ukrainians have now found that even having more than two people gathered together, or even people wearing military uniforms, makes them too obvious and vulnerable to be a viable military element. Soldiers must travel in ones and twos at night and on foot, and lay low in civilian structures during the day.

I have a hard time even seeing how a war can be fought under conditions like these. Certainly, making war more and more difficult is going in the right direction for the species, but I often wonder how (and how much!) the future will differ from the past.