Reader Deontos sent a link to a provocative article on SSRN, The Lawyer-Rent Seeker Myth, by Teresa Schmid. Schmid focuses explicitly on the impact of economic theory on how legal services are delivered. Using county-level data in Oregon, Schmid make a persuasive case that lack of access to legal representation isn’t just a social justice issue but is also an economic problem, since it exacerbates poverty and inequality.

Since the Carter Administration, pundits and citizens accept the notion that America is overlawyered and that legal action constitutes a deadweight cost on economic activity. However, the public does not realize that this point of view was promoted aggressively and is even tacitly accepted in the legal profession despite a lack of evidence. As Schmid describes, the result of this line of thinking going mainstream is the implementation of policies to reduce the access of lower and middle income people to free or affordable legal services. The inability to obtain legal representation has much greater economic costs than the anti-lawyer consensus recognizes.

Indeed , given that the Carter era also saw the first Administration push towards deregulation, it would be logical to expect the number of lawyers per capita to rise, not decline. After all, the “free markets” fantasy of a thin-form government rests critically on individuals being able to enter into contracts and enforce them. That in turn means that the hollowing out of the executive branch and regulations as the main bulwark of consumer protection should lead to an increase in the use of attorneys to defend individual rights. The fact that litigators in particular are depicted as at best a necessary evil and at worse parasites, reveals yet again the true aim of the neoliberal project: not to create a “freer” as in better, society, but to create a tooth-and-claw version of capitalism where the rich and powerful have the “freedom,” meaning the scope of operation, to prey on the lower orders and consolidate their advantaged position.

One of the most revealing sections of Schmid’s paper is her review of the evidence used to promote the idea that the US was suffering from a locust-like plague of too many lawyers. The concern is founded on anti-trust, that any monopoly or cartel arrangement is an exercise in rent seeking. However, it’s worth noting that the intensity of the focus on the idea that there might be too many lawyers isn’t matched with similar worries that there are too many accountants or doctors, which are both professions that use educational attainment and licensing to limit entry. Indeed, the charge that the legal profession has created too many rent-seeking (as in overpaid) lawyers is contradictory. A cartel that allows too much product, in this case attorneys, to be put on the market is a pretty crappy cartel, since an oversupply will depress prices.

It’s also worth noting that the efforts to depict the number of attorneys as a drag on commerce started around the time another initiative to turn the legal system into a vehicle for promoting commerce was starting to get traction: the law and economics movement. Led by Henry Manne, this effort used legal education to inculcate notions that turned long-established foundations of the law on their head. As we wrote in ECONNED:

The law and economics promoters sought to colonize legal minds. And, to a large extent they succeeded. For centuries (literally), jurisprudence had been a multifaceted subject aimed at ordering human affairs. The law and economics advocates wanted none of that. They wanted their narrow construct to play as prominent a role as possible.

For instance, a notion that predates that of the legal practice is equity, that is, fairness. The law in its various forms including legislative, constitutional, private (i.e., contract), judicial, and administrative, is supposed to operate within broad, inherited concepts of equity. Another fundamental premise is the importance of “due process,” meaning adherence to procedures set by the state. By contrast, the “free markets” ideology focuses on efficiency and seeks aggressively to minimize the role of government. The two sets of assumptions are diametrically opposed.

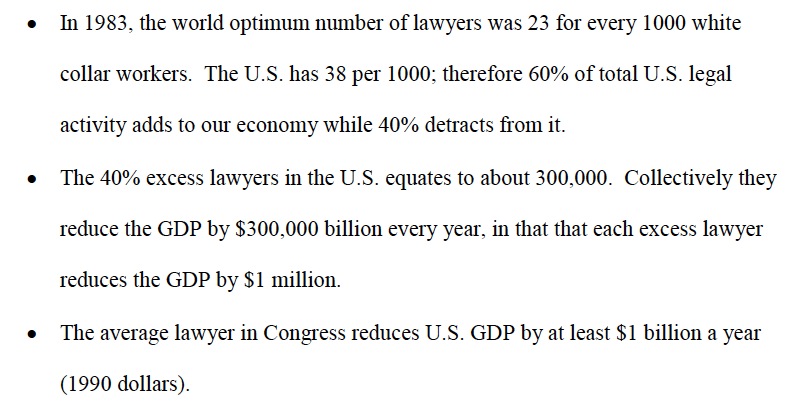

The studies that depicted America as suffering from a plague of lawyers are few and are embarrassing examples of ideology with numbers pretending to be research. For instance, an influential 1984 broadside, The Invisible Foot and the Waste of Nations, by Stephen Magee, William Brock, and Leslie Young, gained traction through the use of an “invisible foot” metaphor to attack attorneys. It also contained such bold formulations as, “By definitinon, rent seeking is just a legalized, white collar version of ordinary criminal activity.” Schmid summarizes some of what Magee et al. tried to pass off as analysis:

The entire analysis hinges off the “world optimum number” which is a huge tell that the “analysis” was the sort of fabrication that in my big firm consulting days would be called “McKinsey intuition.” But it’s worse than that, because the idea that there is a one-size-fits-all number of attorneys across disparate legal systems is obviously a crock.

For instance, Japan when I worked there (the 1980s) was not a contractual society. Everything (and I mean everything) was done on the basis of understandings and relationships and would be argued as events played out. It was extremely difficult to get Japanese clients doing business abroad to understand that an acquisition contract was the deal and that the verbal representations made by the other side meant nothing, and the Japanese client would no recourse except what was in the contract once they signed the agreement. Similarly, one simply did not litigate in Japan. It was worse than getting divorced in the US circa 1955. It meant something was seriously wrong with the party filing the suit. And criminal defense? Fuggedaboudit. Conviction rates in Japan were 99%, largely due to police beating confessions out of suspects. But by contrast, Japanese government officials were feared and respected in Japan, and so Japanese companies didn’t buck their directives. And Japanese executives still take personal responsibility for corporate scandals, as periodic resignations indicate. So the entire social structure of well agreed upon norms, the importance of maintaining good relationships (as in not screwing people and maintaining a good image) and regulators with clout reduces the need for courts as a check and balance to well below the norms in other advanced economies.

Similarly, as John Hempton has pointed out, the US relies more than any other advanced economy on private insurance, such as disability insurance, in place of social safety nets. That means that one would expect more litigation as a result of the resulting greater number of disputes.

And the “optimal” or expected number of lawyer would even vary by state, since some states have much tougher state-level consumer regulation (for instance, in New York, the state insurance regulator has long been aggressive about intervening when consumers file complaints) while other states such as Alabama instead have laws that contemplate that wronged consumers will turn to the courts.

Admittedly, the Magee study did extend some of the thinking of earlier work by Mancur Olson and Gordon Tullock raised doubts about the role of attorneys. However, some of these studies were more nuanced and equivocal in their conclusions. Olson was opposed to guild-like organization, particularly state bar associations. But at the same time, he saw access to courts as a public good:

Olson uncovered, but did not fully explore, the dichotomy arising when access to a public good (the courts) depends on the availability of a private good (legal services) to individuals who are not members of the collective (the organized bar.) Nevertheless, Olson’s logic of collective action demonstrated that government and associations can be subject to similar demands for public and collective goods, and that each may have to rely on taxation models to meet those demands. To that extent, he opened a discussion as to how collective action serves a variety of public interests as well as private interests in the policy arena.

And if the topic is rent-seeking, why are attorneys as a whole targeted? What about the financial services industry, or oligopolists like local broadband providers?

Schid shows how Magee’s “lawyers as parasites” model had a detrimental impact on the funding of legal services for the poor, created as part of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, first as OEO’s Legal Services Program, later as the Legal Services Corporation. Even at its peak, funding was meager relative to need:

Between 1959 and 1971, the total number of lawyers in the United States exclusively employed in serving the poor grew from 292 to 2,534, and the government’s total investment in legal services grew from $2,084,125 to $77,272,710. Even at 1919 poverty levels, however, that represented a distribution of 13,812 poor people per legal aid lawyer31 and a per capita investment of only $2.21, the gap presumably to be filled by private donations and pro bono services to be provided by 355,242 practicing lawyers nation-wide. The scope of this assumption is mind-boggling: in addition to maintaining a practice sufficient for his or her own support, under this model every attorney in the United States would be expected to volunteer enough hours to meet the legal needs of approximately 100 poor people.

Nevertheless, the OEO Legal Services Program learned how to punch above its weight:

[T]he Legal Services Program …adopted a policy of advancing impact litigation, especially cases that protected entitlements to the new programs created as part of the War On Poverty…This activity resulted in decisions such as Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 638 (1969) [prohibiting arbitrary denial of welfare benefits to legitimate recipients]; Goldberg v. Kelley, 397 U.S. 254 (1970) [requiring government to provide due process before denying benefits]; and Edwards v. Habib, 397 F. 2d (D.C. Cir. 1968) [prohibiting retaliatory eviction from residential housing.]

Both the funding and scope of this representation has been curtailed considerably. Not only was LSC’s funding cut well below the level of “minimum access” (two lawyers for every 10,000 poor people) but its scope was narrowed as well:

The funding cuts of 1996 were accompanied by the restrictions on LSC activities, the bulk of which that are still in force today:36 Section 504(a) prohibits the use of LSC funds for 19 specific activities, many of which had previously been central to the legal aid mission. These restrictions included prohibitions on lobbying; participating in class actions; representing any aliens not lawfully present in the United States (later overruled by the Supreme Court so as to permit representation of victims of domestic violence); defending a person subject to an eviction proceeding from public housing if the person has been charged (not convicted) of drug activity; participating in any litigation with respect to abortion; participating in any litigation on behalf of a person incarcerated in a federal, state or local prison (whether or not convicted of a crime); and claiming attorneys’ fees from litigation, even if such fees are permitted or even required to be paid under federal or state law. In sum, federal funding for legal aid was effectively limited to serving individual clients on a case-by-case basis rather than pursuing systemic legal reform. As a result, enforcement of consumer protection laws and public safety regulations through private litigation has become increasingly important as a vehicle for compensating consumers injured by major corporations.

Scmid relies on detailed county-level work in Oregon to demonstrate that limited access to legal counsel worsens poverty. For instance, in the case of domestic disputes, while police can intervene, the most they can do is stabilize a bad situation. In family court, it takes effective representation to assure that the unwinding of a marriage results in two households that have decent odds of making it from an economic perspective. Similarly, in California and New York, between 70% and 90% of borrowers fighting foreclosure were pro se. If a much larger proportion had had good attorneys, it’s hard to imagine that the authorities would have been able to paper over servicing and chain of title abuses.

Schmid’s analysis of detailed information in four Oregon counties on population growth, changes in poverty rates, domestic violence, nights in shelters (and unmet demand for shelter beds) and divorce rates indicates that sufficient access to representation to allow for dissolution of marriages is an anti-poverty measure. And intuitively, there are many other ways that having a lawyer can make a big difference in the financial standing of low-income people, including foreclosure cases, landlord-tenant disputes, employment cases, and consumer fraud.

Schmid points out that the Fed’s low interest rate policies are hurting poor people through reducing support for legal aid. Banks pay interest on lawyers’ escrow accounts, and programs implemented on a state level called Interest on Lawyers’ Client Trust Accounts allow for the interest paid to help fund legal services. As Schmid notes:

In light of the results yielded by this study on how increased access to legal

services is associated with declines in both domestic violence and poverty, it is likely that the precipitous drop in IOLTA revenues resulting from the drop in the Federal Funds rate provides a partial explanation. A significant decrease in the availability of legal services would deprive low-income Oregonians of legal protections for jobs, consumer protection, even entitlements such as welfare and Medicare benefits. Predictably, that would magnify the effects of an economic recession, making poverty more intractable and

recovery more elusive.

Schnid proposes a variety of remedies, including having bank lending under IOLTA count towards their Community Reinvestment Act requirements, as well as restoring tax-preferred prepaid legal services as an employee benefit. But it is not clear how to remedy the bigger issue that she flags as the premise of her paper: the belief that reducing the number of lawyers is pro-growth, particularly when other advanced economies are reaching the opposite conclusion. But here, fewer lawyers means unequal access to the court system, an outcome that serves the interest of the rich and powerful well. Thus it’s unlikely that we’ll see any change on this front soon.

I like this article. Law at its best should represent a level playing field for how a society wants to be structured. We seem to be at a two tiered system which is pulling at the fabric of western society.

‘Polanyi defines socialism as “the tendency inherent in an industrial civilization to transcend the self-regulating market by consciously subordinating it to a democratic society.” This definition allows for a continuing role for markets within socialist societies.’ Fred Block in the 2001 Introduction to Polanyi’s ‘The Great Transformation’ (originally published 1944)

He wrote this in the early 1940s but Polanyi seemed to have amazing insights into how economics are ’embedded’ and subordinated to politics, religion, and social relations. He felt this very strongly to the point that ignoring these issues is not sustainable. People will eventually fight back if they become totally degraded. A good legal system can help prevent that.

He felt that labor (human effort and activity) and land (the environment) cannot be commodified. These basic aspects of human rights and environmental protection could use a strong legal support system. I don’t think all lawyers want to do corporate law. :)

Not two, but three. The elites, a “free pass” system where no one is ever guilty of anything (including, often enough, rape and child molestation), the middle/working class, a reasonable if difficult approximation of what an ideal system would be, and the poverty class, which effectively has ceased to provide any relief whatsoever from anyone who sites them as prey.

“Law at its best should represent a level playing field for how a society wants to be structured.”

Law is 99.9% about property and who gets to keep it.

Sure, lawyers are one of those necessary evils in society. You want the best the lawyer you can buy when you are in a pinch. What becomes upsetting are the fees. They charge by the minute for all sorts of activities, something other professions do not do. Oh, yea, they get paid before you do when you win a case, which is another bone of contention.

Are there too many experienced lawyers running around wrecking the economy. I would say no. The issue is they’ve erected high barriers for entry into the profession. Here in tiny Belgium lawyers can only practice within their confined province. For instance, a Brussels lawyer cannot represent someone in neighboring Flanders. Although the EU likes to talk up a good game on movement of services, they carved out exemptions for lawyers. In other words, lawyers don’t get much competition on fees. The situation is so acute lawyers will tell you upfront if a case merits a court visit, because they know their fees could overwhelm the potential award.

This Libertarian argument is the worst. The practical reasons for the barriers is know how and expertise about how the laws in a particular jurisdiction in the U.S. (i.e, federal, stare and local laws differ ) the relationship between competency and jurisdictional legal issues is that the less a lawyer knows about a subject matter especially in a particular jurisdiction the more likely the lawyer will provide incompetent representation.

Or maybe a less complicated legal system is needed?

That’s a very naive position. Living in a society of 320 million people is complicated. Even if you eliminated inequality. Complexity is just the reality of systems.

True, but complexity creates its own problems. For one thing it is effectively a subsidy (a massive subsidy) to the legal professionals, who then have every reason to advocate for opaque, arcane language with which only they are equipped to deal.

Most lawyers since the 90s are trained under the “plain English” paradigm just as they are trained under law and economics. Nowadays when someone speaks of legalese, I assume they are trading on a lack of knowledge about the profession in the sane was that the article describes. The issue isn’t legalese. Its complex legal ideas often incorporating a lot of case law, analysis etc into writing along with complicated non legal facts That’s often a lot to expect clients of a layperson to fully grasp until the crap hits the fan. I work with sophisticated clients for whom its an issue although they have extensive exposure to lawyers . In fact the challenge doesn’t even take into account many lawyers now actively assist clients in skirting the law . My point is there is only so much dumbing down you can do if you are writing an indemnification clause or drafting a motion . There is only so much explanation.

Legalese, to most common people is pages of fine print to hide intent. It is often simple as the law that requires notation of interest amount be on a credit card.

The greatest legalese is the crap that comes as laws from congress and senate which runs into thousands of pages, The meaning to be determined by a court at some future date.

Your comment reflects the common delusion that things are simple just because…Your failing to properly hammer out the details is simple. It makes easier for you to be screwed bc there are several hundred years of jurisprudence born out of disputes between those common people who you like to imagine all think alike and lack their own interests. Toy live in a society with 320 million people. If you

Think the rules that 320million people ate simple or should be ,then I think you are ill suited to addressing issues of economic justice., which was the point of the article

Ditto, would recommend a movie for you (A man for all seasons).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Man_for_All_Seasons_(1966_film)

ding.

Legislative detritus is written and assembled by legions of staffers, no single one of whom has read the entire bill/law. Who’s read the entire, no less fully understood, the affordable care act? The very strategy of how legislative sausages are written, assembled, presented, debated and voted on is intended to obfuscate for the advantage of special interests.

Regarding “plain english”, try reading the T&Cs on the next piece of software you buy or a credit card agreement. Sure it’s written in clauses and savvy people understand what to look for, but at the core how complicated does it really need to be to express intent before it’s just obfuscation?

If the intent of lawyers is to present in “plain english” (enable comprehension?) why print in light gray w/small small font?

We need more lawyers? Who’s to say. Surely the issue is the barrier to fair access to competent legal representation. Not sure how cookie cuttering out more of them lowers the access barrier?. I would expect that will just infiltrate more lawyers into other professions. Not sure if that is a wise choice or not.

“Lawyering” is a closed guild, how much Xerox machine lawyering could be as/more effectively accomplished by paralegals?

Another point is how much social behavior legislation should be repealed? I am guessing there is ALOT of low hanging fruit to be removed that would make access to lawyers theoretically more available ( percapita legal manhours/population) with the present number of lawyers.

Low hanging fruit. Almost all laws written beyond the ten commands are for obfuscation of the law.

Maybe fewer than ten?

Cue classic G. Carlin piece:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1KiCEJoX9kE

George Carlin – The Ten Commandments – Live Stand Up Comedy

optimader, thanks, it was great.

It’s worse than you COULD imagine. Previous statues and precedents are likely to override your simple plain English agreement. Software agreements are a good example. If you provide ANY kind of warrantee on your product, you automagically import a couple of hundred pages of law relating to “strict liability”, consequential damages, etc.

For this reason, you can’t write a simple plain-English promise that if it’s broke you’ll fix it.

Most software companies include phrases that say that they take no responsibility, their product may not work at all, and if it doesn’t, they don’t care and are not responsible.

As someone reasonable famous said: “The law is an ass”.

Tech issues were actually my area

They are extremely complicated

IP, risk allocation, laws like export controls etc

The experienced lawyer involved will know the legal landscape in which the document is drafted

You don’t

The issue is there is an unequal level of understanding between the lawyer awareness and the clients that leads the client to think its easy

Clients don’t like to admit they don’t know

Plain English means if you read it you can understand it if you

Take time to understand the issues

It doesn’t mean well I believe in this folksy View of reality where I don’t need to read or think about it or I think its unfair that I need to say think about the warranty

Tech issues were actually my area

They are extremely complicated

IP, risk allocation, laws like export controls etc

The experienced lawyer involved will know the legal landscape in which the document is drafted

You don’t

The issue is there is an unequal level of understanding between the lawyer awareness and the clients that leads the client to think its easy

Clients don’t like to admit they don’t know

Right on. I’m often reminded of how simple things can be when we want them to be simple. The Constitution, Declaration of Independence, Social Security Act of 1935 (Economic Security Act), Civil Rights Act of 1964, Emancipation Proclamation; all together, less than 100 pages. And who can forget Paulson’s 3 page wonder of bipartisan bankster bailoutery?

Of course, when we don’t want things to be simple, we write thousand-page long documents just to make minor tweaks to existing laws.

Are you Joking?

Con law has literally an entire system set up to adjudicate the complex ways the laws are applied ? That document has no meaning without case law

Something you should know from a basic high school course in US CivIcs

The same is true in applying the other actual laws

I am stunned by the lack of basic legal literacy here

Of course Constitutional law is complex. It takes a lot of verbage to change the meaning of simple passages like this:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

Yes, our society is complex. But no, the laws do not need to be complex or verbose. The Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act is vastly longer then the original Glass Steagall Act. The Glass Steagall Act was 37 pages long. I’m not sure exactly how long Dodd Frank is — it probably depends on whether it’s single spaced or double spaced. I’ve seen claims of 2319 pages, but when I got a PDF from https://beta.congress.gov/111/bills/hr4173/BILLS-111hr4173enr.pdf, it was 848 pages long (definitely a dense single spaced format). In any event, Dodd Frank is ridiculously long, and serves as a subsidy for the legal profession.

Let’s not forget the tax code, either. There’s no rational justification for the length and complexity of the U.S. federal tax code, other than to create obscurity which facilitates wealth protection for the rich, and another subsidy for the legal and accounting professions.

I can’t take any if you seriously

Is that the best justification you can come up with for the complexity of the tax code and Dodd Frank?

Dodd Frank is complex because it was meant to be a headfake. For instance, a huge number of its provisions were kicked over into “studies” which meant (as everyone understood) the bank lobbyists would get a second go at it.

The tax code is full of pork. That’s why it is complex.

Oh, and perhaps more important, you put your fingers in your ears and yell “Nah nah nah” when lawyers (and layepeople) try telling you that contracts and statutes don’t operate in a vacuum, they live in a system of established CASE LAW (court decisions) and those writings have to be interpreted in that context.

Next?

It’s going to be surreal when there’s case law and regulations that interpret Dodd Frank! There’ll be even more complexity to keep the banks’ lawyers busy!

I don’t feel like I’m having a conversation with an intellectually honest crowd when

Having to explain basics like case law and. 320 million people means complexity

Beyond a certain threshold, the population size should have no effect on the complexity of the legal system. I see no reason why U.S. law should be any more complex fro a population of 320 million than it was when the population was 150 million.

China and India each have about 4 times as many people as the U.S. Should their legal systems be correspondingly more complex?

Jesper’s comment that a less complicated legal system is needed is completely valid. Jesper didn’t say that the legal system should be trivially simple, and I’m not saying that, either. But it desperately needs to be simpler than it currently is. Dodd Frank and the tax code aren’t the only examples of the excessive complexity of our laws. Obamacare is another example, and the regulations that lie atop so many of our laws add to the complexity. I’m not anti-regulation, but what we need is better enforcement of good regulations rather than layer upon layer of regulations that probably won’t be enforced.

Washunate also made an excellent point that the number of people with a legal degree and people’s access to legal representation are two separate issues.

Complexity in the legal system has everything to do with property and Capital exchange. Social values are quite simple and always have been. There lies the crux of the problem. The complexity is where the money is, and that is why the legal system has become less a representation of sound ethical human judgement and more an arbiter of Capital allocation. It should be no surprise that the less well off lawyers are the ones dealing with the social values end of the spectrum (i.e. public defense, etc.). Take away most law giving flexibility to Corporations and the wealthy (able to buy lawyers able to speak the divine incantations) and you have a very streamlined system able to serve all people far more effectively.

“Social values are quite simple and always have been”

What “social value” legislation doesn’t involve a “property and Capital exchange”?

Property and Capital are legal concepts. My point being law can clarify that it is not okay to steal from someone, but it also says what is or is not your property. This is where I have a problem. Social values are not part of the current legal/economic paradigm in my book and the law is self referential (as compared to being adapted to the relevance of the situation in question). If I occupy a home that is in disrepair and fix it up but it is owned by an absentee owner I have no legal claim to it, yet social values (and reason) would indicate that that home (ironically the property as a legal concept) and the people living around the home are much better off because of what I did (this is not an abstract example either, it is done everyday). Though through the legal system I am outside of the law with this action. We are conditioned to consider property as a timeless component of the human condition and sometimes I wonder if we feel that way about Capital as well.

Well written.

“Property and Capital are legal concepts.”

Isn’t “social value” a legal concept?

I applied to intellectual property law?

Obscenity Law (Miller test)?

Applied to intellectual property law?

I agree although the legal system is a byproduct of society. Society is generally reactionary so laws are generally passed AFTER something bad happens. A less complicated legal system would require people to respect each other more.

On the other hand when 26 of the 43 separate US presidents (44 but one guy is counted twice) have been lawyers, the path toward a complex legal system seems more predictable.

However the point that many people are underrepresented legally is a black eye on the nation as a whole. If a white collar worker or friend of a politician suffers an injustice we see much quicker results than when an unknown blue collar worker or homeless person suffers a similar injustice. On that note, the issue is much more complex because it doesn’t matter if we are talking about inner city black youth or middle aged white farmers in an isolated village, both groups of underrepresented people (are stereotypically thought to) have a culture of distrust for the government and their own methods for rectifying injustice.

middle class ideas about respect (eg, respect or civility will save the day) are not a solution to complexity. People have different interests and values and laws will be complex because of it as will the process of resolving differences even if everyone remains perfectly civil.

‘When 26 of the 43 separate US presidents (44 but one guy is counted twice) have been lawyers, the path toward a complex legal system seems more predictable.’

From a 2012 article about the previous Congress:

‘The share of senators who were lawyers peaked at 51 percent in the 92nd Congress, which was in session in 1971 and 1972. It’s now at 37 percent. Lawyers account for 23.91 percent of today’s House, down from a high of 42.56 percent in the 87th Congress (1961-62).’

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/23/first-thing-we-do-lets-elect-all-the-lawyers/

————

Lawyers in Congress are still represented at 30 or more times their prevalence in the labor force. There’s an inherent conflict of interest in putting those who benefit from complexification in charge of the legislative sausage factory. It’s as big a conflict as putting a bank cartel (the Fed) in charge of monetary policy.

Infinitely worse are two-lawyer couples in politics, such as the Obamas and the Clintons. I barf!

Yes it is shocking that a profession that interprets the law would be attracted to one that makes them. I also think it completely logical to conclude that bc they are lawyers therefore that explains their policies rather than their policies being unconnected to their prior profession. It certainly exit subs why all the non lawyers hold similar policy views.

Ditto is a lawyer

Actually I’m starting my own mom and pop

I used to be one

I spent most of my day dealing with Folks who would babble about how its all simple just like you abc the it get are doing

It ended up making my job miserable and a lot harder

I was an honest one rather than what the profession has become in I part in response to client is right thinking

So if the client says its smile we are supposed to parrot that thinking

A master navigator does not necessarily make for a master ship-builder. The captain, crew and passengers can however, as CITIZENS, provide honest feedback to the builder so he/she can design-build a better ship experience for ALL, in future journeys. Then “we” can pursue the altruistic goal of embedding honesty, fairness and ‘justice’ into the ethos of ship-building…or at least find purpose in pushing that stone up the hill.

Best comment ever.

Dodd-Frank vs Glass-Seagall?

Might be more examples on simpler things. Only way to not find ways to simplify is not looking for ways to simplify.

Not sure why you’re so opposed to the possibility of simplifying. If I was a cynic then I might think you’re in law and therefore benefit from the complexity of law.

For the most part, a poor person’s individual legal problems are not that complex. I worked in public housing for many years and spent a lot of time in the New York housing court. Most of the tenant’s complaint could be handled by someone with very little legal training or even pro-se. The only people who needed professional counsel were tenants we tried to evict for reasons other than non-payment or tenant who wished to remain in the apartment after family members died. In these situation, case law is fairly complex and you need a lawyer who knows how to formally argue your case before a judge. Most poor people’s legal problem are not that complicated. The one exception is criminal defense. In those cases, a really good lawyer can make the difference between jail time and freedom.

Of course, poor people would benefit from changes in public policy. Much of our politics is dominated by conservatives, so that would be a difficult task

I imagine the point about linking legal representation to economic status goes beyond housing case (which despite your claim can become complicated) is that there are a range of areas in which over a life time of the average person v say a well financed company, the individual will be screwed. Off top my head contracts as a consumer and arbitration clauses or the rights of the employee greatly effect the allocation of risks taken on by the poor and the middle class. In fact, one of the issues is that risk is being shifted to people often without their awareness. So that lack of qualified representation with know how in fact increases risks in ways that are very complicated.

Great post, Yves. But I think this theme goes back farther than the Cater administration, all the way to the ’30s and even earlier. The wealthy, who often saw themselves as the “natural aristocracy”, and therefore rulers, of America certainly hated the expansion of rights and the concept of due process that came with the New Deal and the rise of organized labor. They also hated the greatly expanded diversity of American society that came with the waves of immigration at the end of the 19th Century, which also saw a great expansion in demands to enforce the Bill of Rights.

In fact, I suspect that the foundation for the law and economics movement can be traced to the University of Chicago’s Law School in the 1930s, whose dean had a visceral hatred of the New Deal and often lectured how the laws built around New Deal were violating basic economic principles that could explain and justify the business practices that were being regulated and outlawed. Couple that with the rise of the civil rights movement in the ’50s and ’60s, in which many Americans had to face the ugly reality behind the the McCarthy era facade of harmony and wealthy, and you have basis for a Carter-era backlash.

Frankly, I think the subjects typically taught in a first-year law school curriculum should be taught to high school juniors and seniors—contracts, torts, constitutional law, property, procedure, criminal law. This would be far more productive than worrying about “STEM”.

We need streamlined access to the Rule Of Law. But like Healthcare, this is the last thing the Profiteers want. And, like Healthcare, no matter how many lawyers (or doctors) you have a large percentage of the law (or healthcare) is defective.

I recommend that anyone commenting here actually spend a day at your local/state/federal courthouse. I have done so and it is a real eye-ear opener. Listen in the corridors for deals being made. Also, if you have a beef with someone, consider streamlined Small Claims Court. In my jurisdiction, it can settle some disputes up to $25000. I’ve been twice in two different jurisdictions and won both times. Keep in mind also that the vast majority of cases in the US NEVER GO TO TRIAL, indicating that forces other than the citizen’s conventional courtroom ideas are at work.

Here is an unusual view of American law:

“Until this past year I had not realized, or connected the similarities between this fantasy holodeck and the shocking reality of our American courtrooms today, where, as in the holodeck, nothing is as it appears. But, like so many other things in life, as one accumulates knowledge, and uses their own experiences, observation skills, wisdom, and reevaluates what has been seen and heard, a reality or a truth becomes more apparent.

The American courtroom is created by a legal aristocracy who will stop at nothing to keep money and power in the hands of a few “power-elite” control mongers. Much to my disappointment, at this stage in my legal career the eerie similarities between the runaway American courts and the fantasy holodeck can no longer be denied. This Divine Right of Kings is still alive and well, but hidden carefully within the bigger holodeck called America….

What I now refer to as the “courtroom holodeck” is the scene of the crime, and the stage where this chimera is played out. In this virtual reality the judges and attorney(s) are holograms (mere images of justice), all working in the labyrinth of a “Litigation Vortex.” The unsuspecting public who either gets sucked into the vortex (unwillingly brought into court) or suckered into the maelstrom (thinking that justice would be received through the legal system), are real characters, but they do not realize they are on the court holodeck, nor do they realize that they are not being protected, or zealously represented as was taught to them in our government-funded elementary schools. They do not realize that nothing is as it appears.”

http://www.ejfi.org/Courts/Courts-4.htm

“nothing is as it appears” surely resonates with me.

Is the local or state courthouse open to the public to sit in on? I wouldn’t even know.

But I have heard stories like yours about how those who actually have to sit in court all day (criminal not litigation) waiting for their case to come up observe most of the cases don’t go to court. Something I half note, when the bleating begins, about rule of law, why don’t people trust the legal system, etc. …

Guess who was the director of OEO from 1969-1970, when many of my friends went to work there as newly-minted & idealistic lawyers? Donald Rumsfeld. Yes, THAT Donald Rumsfeld.

Rumsfeld didn’t want the job, had voted against OEO’s creation under LBJ, and opposed its mission. He hired as his underlings Frank Carlucci & Dick Cheney.

Our government, always doing the best for “the poors.”

The only serious purposes of our legal system are to enforce the contract claims of the business rich against one another, the contract claims of the business rich against the poor, and the prohibitions reining in entrepreneurial behavior of those industrious, independent minded and predatory lower class individualists who refuse to cave in and get a job. All other effects and consequences are anecdotal and random.

IMO, the problem is that there are parts of law which are over-served (namely too many corporate lawyers, with too few of them worth their salt), and parts of law (low-level criminal law, especially pro-bono) which are under-served. Same as in (say) banking – overbanking in some sectors, massive under-banking in others (serving poor..). Not enough money in the underserved part, too much money in the other.

Talking about about having too many or too few lawyers entirely ignores that a criminal lawyer is an entirely different beast from corporate M&A one.

Could we use more funding for subsidized legal services? Of course we could. But that doesn’t mean we need more lawyers! Each year, half of current law school grads are unable to secure legal employment, because there just aren’t enough jobs. There are plenty of unemployed lawyers to hire first.

Is it that there really aren’t enough jobs, or that there aren’t enough jobs at pay levels high enough for them to pay down the student debt they’ve accumulated going through school? As indicated, look at the stats in the article on how many people had to represent themselves in foreclosure. I can tell you that there was and is a dearth of foreclosure defense lawyers. Admittedly, many of the people who were in foreclosure were destitute and could not pay for a lawyer, but many had problems with HAMP or were victims of servicing snafus. In those cases, getting a lawyer involved for a few hours could have forestalled disaster.

A friend just finished his tax law certification, which he decided to get after failing to find employment with just his plain ol’ law degree. He’ll work for anyone, but there doesn’t seem to be anybody hiring, public or private sector.

There’s plenty of demand for the services of lawyers, as you point out, but it’s not effective demand (i.e. it’s demand from people who can’t pay for it), so it doesn’t count. It should, of course, but it doesn’t.

I’ve heard this too, but why are fees so high? 300-400, thousands of dollars to write a few letters or a document, which likely took a few minutes but was padded to the nearest, next hour? Considering the almost non-existent overhead, where are the fees going? A physician has x-rays, refigeration medicines, surgical equipment, nurses, records, insurance trouble shooters, etc. Why don’t some of the unemployed lawyers charge 100 dollars/hour?

Attorneys are not permitted to pad to the next hour. It varies by state, but the biggest billing time increment that exists I believe is 15 minutes, and I also believe some states make attorneys whack hours into 10 or even 6 minute slices.

In many cases, you are paying for making a credible threat. If you as an individual write an angry letter, the recipient can ignore you. If an attorney who is licensed in the state in which the offending party is located sends a nastygram on your behalf, the threat is that you will escalate to litigation. And the attorney has to evidence knowledge of the relevant legal issues for the nastygram to be credible. Even a frivolous suit takes $5000 to $15000 to make go away. So contrary to your assertion, a letter on legal letterhead is extremely valuable. I’ve been forced to use them on occasion and they’ve been worth every penny I’ve paid for them.

As a consultant, I charged $500 to $600 an hour, had even less overhead than a lawyer (no need to pay for bar association fees or continuing legal education costs) and clients happily paid that.

You basically are saying you don’t value and aren’t prepared to pay for professional services. Honestly, your attitude is shockingly naive.

Law school enrollments have dwindled considerably since the 2008 crash in almost all law schools. A lot of layoffs or buyouts of tenured profs happening in many law schools, plus law school staff of all types are facing lay offs (or have been laid off). The 2008 crash resulted in shrinking law firms, esp the Bigs. Where govt lawyer jobs often used to go begging for what used to be perceived as a 2d rate job, now those positions are filled and are hard to obtain.

And yes, after someone has gotten in debt to gain an undergrad degree, then they’re faced with racking up something close to $100k (plus/minus) to obtain a JD. It’s daunting, unless you come from the 1% or at least maybe the 5%. Only the very very top law grads from the top first tier law schools are hired in the Big firms (that pay fat, but definitely thinner than prior to 2008, salaries). It’s a small minority scrambling for those few high salary jobs. The rest scramble for what’s left over.

Hanging out your own shingle is always an option, but for someone newly minted as an attorney, that’s tough with huge debt to pay off. It’s unlikely that a newbie attorney will make much money on their own, possibly even for the rest of their working lives.

I have worked in the legal field for longer than I care to reveal (not an attorney). While I think I deserve my salary, believe me, I make a LOT more than many solo attorneys do. It’s tough out there if you don’t have money or connections.

The evidence seems to suggest that there really aren’t enough legal jobs. Some links below:

http://lawschooltuitionbubble.wordpress.com/original-research-updated/law-graduate-overproduction/

http://lawschooltuitionbubble.wordpress.com/original-research-updated/lawyer-overproduction/

Student debt is the biggie. I am a public defender at the appellate level (still a newbie, graduation 2010) and there is no way in hell I would have been able to do what I do without a constellation of incredible luck. I had no debt b/c I picked the 4th tier school with the full scholarship over the prestigious one charging full freight, and my spouse was an engineer who luckily turned out to be excellent patent attorney material and seems to fit nicely into the monied Biglaw world that frankly horrifies me. My total earnings last year were around $25k. Potential earnings in my career path are what most would consider solid middle class (eventual 65-90k) which sounds great until you consider that many are graduating with 100-250k in loans. Expenses for running a practice are also rather high, with a couple thousand a year taken up by licensing fees, insurance, etc. And I work out of a PO box without an office. Most of the few young people who do what I do come from family money, went to elite schools, and are dicking around with public service for a couple of years to look less like neoliberal slime on their resumes so they can run for office. The rest are the old-timers who came on in the 70s when this was less of a problem. All my idealistic working & middle class chums who bit the bullet and went to law school assuming they’d get rich “helping people” have quit after being totally unable to get a job that could service their debt. Most are now selling insurance, although a few hung on for several years trying to churn as many billable cases as possible in “solo practices” that were basically desperation gambits. I expect many ended up cheating their clients quite badly.

The underlying issue of this post has nothing to do with legal access for the marginalized and the scarcity of lawyers. [Hilarious, btw–The US and its “shortage” of lawyers.]

No, this post is about the fact that Progressivism, taken to its logical conclusion, has an Enforcement Problem. A huge Enforcement Problem.

Obviously, Warren-Progressives don’t want to be associated with Libertarians and the shared disgust over Ferguson. So what’s the answer for like-minded (but tolerant–so long as you are like minded), environmentally concerned, equality demanding, gender-neutral, racially conscious, spiritual, but not religious person peoples?

Lawyers. Lots of lawyers. Teams of lawyers. But first: We need to help the poor! And battered women too! Oh, and when we’re done–imagine what good Our Team will do for the environment!

Law is a step away from brute exercises of power via persuasion (through religion, cultural practice, ceremony, etc.) and violence, but I would argue that law further intrenches inequalities and power rather than challenges them. Lawyers are the modern secular equivalent of the Catholic priests of yore, salvation is only had through their guidance. The Catholic model with the priest at the cultural helm allowed for a functional society but eventually Europeans learned to move on. Lawyers, being the priests of the secular age, I’m sensing are in their twilight years as well. Information and social awareness is widespread, yet social justice thorough legalism is becoming less of a reality not from a lack of understanding of what is ethical, moral, or just, but a fixation on a ritualized mode of exposing it with a specific bloated lexicon. We should take what is good about legalism: equal footing before the law (though this has never happened in practice), formalized permissions/restrictions, protocol and procedure (if it is ethical and effective), and discard what is not needed, unnecessary hierarchy (explicit in the relationship of the citizen to the state via attorneys and judges), the undeniable “price” of justice through the Capitalist model of legalism (many hard-line Marxists will argue legality itself is exploitative and alienating but I’m not willing to go that far, yet). Legalism as we know it in the West is ineffective via its structure not its actors.

Well said. +1000

This is a silly article.

There is no shortage of lawyers: there is a shortage of paying clients. The average legal education costs upwards of $200,000 ($250,000 including undergraduate studies). Outside of the top 20 law schools (out of 202), between 30 and 60% of graduates are unemployed 9 months after graduation. The average salary for lawyers in the first five years of practice is about $60,000. You may be able to make more in your own practice, but starting your own law office requires capital, which for those of us in the bottom 99% is difficult to access with six figures of non-dischargeable student debt.

There are tens of thousands of unemployed lawyers in this country who’d be happy to work if someone would pay them.

That says that legal education, like higher education generally, is overpriced. You apparently missed, for instance, the number of people who represented themselves pro se in foreclosures. Some of them (not a large % but some) had some $ before they hit the wall and some were victims of servicing abuses (as in they paid on time but the bank didn’t credit their payments properly). I can tell you that there were nowhere near enough foreclosure defense attorneys relative to need (as in clients that could pay something had trouble finding competent representation).

People still need lawyers for all sorts of things, particularly now that companies even more engage in what Elizabeth Warren calls tricks and traps. That, BTW, in to some degree due to class action litigation and antitrust litigation have become more restricted. So the circumscribing of bigger ticket suits that would constrain powerful companies has shifted the need for legal services to abused individuals, many of whom can’t pay enough to fight back. Nicely played.

Both Yves and aesquire are correct. I would argue that there’s no shortage of lawyers, even given the shrinking enrollments in law schools. There’s a shortage of paying clients. Some lawyers truly are civic minded and would like to work with clients who have no money in order to shepherd them through the legal system, but then, how does that lawyer eat & pay the bills.

Indeed, Yves, I can state unhesitatingly that in my field (where we serve a lot of self-represented litigants) we see few attorneys interested in representing those in foreclosure. Again, I don’t think it’s through lack of not feeling like doing that work. It’s because they cannot get paid. And so how does the lawyer eat and pay bills, etc.

There are fewer and fewer legal services available to those with little to no money, and what is there is mainly accessible only to really poor or indigent people (which is good) but often also is only available for certain types of cases. After all, no one attorney is capable of handling every single kind of legal issue; they specialize.

Even before the crash, we began to see more and more middle class citizens needing some kind of free or low-cost legal services because they couldn’t afford the high attorney fees (even solo & small law firm lawyers charge more than many can afford). Where the crunch comes for most “regular” citizens are these legal areas (not an exhaustive list): family law especially (in CA 70% of family law matters are handled by self-rep litigants without an attorney), trusts/estates/wills + probate, landlord/tenant, traffic violations, various types of small claims (which, as another commenter pointed out, can be handled by a self-rep litigant, but you still have to follow certain procedures), debt collection & foreclosure, and criminal law issues.

Most of the people we see simply cannot afford a lawyer, but there’s few services out there to assist them through the complexities of the legal system. This, then, creates log-jams in the courts, where citizens attempt to limp their way through the legal system without benefit of legal representation.

The 1% and the corporations refuse to pay their fair share of taxes, and they have convinced a significant portion of the populace that, somehow, it’s “unfair” to have the govt pay for some type of legal representation for those who truly cannot afford it. It’s yet another conundrum of US life. The result is inefficient and ineffective use of the court system, which then citizens complain about that waste. And the beat goes on.

We do see, though, more attorneys nowadays attempting to learn how to practice law on their own or in small firms. But still, they have to charge enough to pay their bills. It’s not a complete answer to the current situation.

I completely agree with Yves that legal education (indeed, higher education across the board) is way too expensive. It’s goddamn scandalous as a matter of fact. I also agree that there aren’t enough lawyers in public interest fields to meet demand. But again, lawyers have to keep the lights on, just like any other business.

I count myself among the many lawyers in my community who would love to help people with foreclosures and debt collection problems. Sadly, I’ve tried this route, and it just doesn’t pay the bills (and by bills I mean office rent, professional liability insurance, and debt repayment, not the mortgage on my beach house).

If the state funded indigent representation in civil cases to the same extent they fund representation in criminal cases you’d see the ranks of public interest attorneys swell considerably. But there’s no constitutional right to counsel in civil matters, so the state isn’t going to fund what it doesn’t have to fund.

Yeah, I feel kind of sorry for Schmid. She’s talking about important issues of access to legal representation but seems to completely miss the most obvious facet of the legal profession today – lawyers who desperately want to do good can’t earn enough money to feed themselves, never mind pay for all of life’s other expenses.

Our system is curtailing access to justice because that’s what the authoritarians want, not because there aren’t lawyers interested in defending justice. It’s not a consequence of a lack of lawyers; it is an end goal in and of itself.

The Constitution guarantees everyone legal representation. The Constitution also empowers the government to print money whenever it needs to. To say there isn’t enough money around to pay for lawyers is nonsense. The Constitution requires that there is.

Now of course the stock answer is that this isn’t politically feasible, but that’s simply an admission that the people who run the show don’t want us to have a real legal system, and that can’t be an acceptable answer.

What is the correlation between increase in population and increase in complexity of laws?

More consumers lead to more complex legislation?

More house-owners lead to more complex legislation?

More employees and more employers lead to more complex legislation?

One new paragraph of law for every new citizen?

Its actually basic social dynamics

are the rules for interaction between ten people easier than the rules for a 1000?

I notice many people try to pull up things like frank Dodd but what abut a landlord tenant case or a bankruptcy or child support or a contract for a car etc or a tort etc

Of course there is a fundamental need for attorneys in our society. But there’s also a huge amount of unnecessary complexity that causes far more problems than solutions.

CA is working on reducing some of that complexity at the lower court levels, but some issues simply cannot be reduced further. Family law is one area where there’s simply no easy answers. IF the couple is willing to do a non-contentious divorce, THEN it can be relatively easy and painless. But IF the couple is committed to making life a misery for their erstwhile partner, THEN it rapidly becomes complex, difficult and time-consuming.

The latter is what most “regular” citizens are dealing with. That and family law, which, in itself, can become very contentious and complex. CA is actually better than some states in providing Family Law Facilitators & mediators in their Family Law Courts. They help a lot, but some citizens could benefit from the assistance of an attorney.

There is a legal publisher called Nolo (now owned by Ebsco), which publishes a variety of books geared to the layman or self-rep litigant. Clearly these books don’t cover fields like large corporation laws. They are aimed at helping the “average citizen” negotiate their way through landlord/tenant disputes, neighbor disputes, traffic court, small claims, etc. The issues we see are citizens who have literacy issues and/or where English is a second language. OR citizens who really don’t feel like reading a book and spending the time it takes to figure stuff out on their own.

Quite honestly, citizens CAN (and do) handle their own legal matters and can be successful (we see it every day), BUT they have to be committed to spending time on working on it. Too often we see citizens who want “THE” answer or “THE” form, and expect to grab ‘n go and have the problem go away quickly. The system doesn’t work that way.

Can’t argue with the reasoning or the merits of the goal. Unfortunately the reality of my experience with lawyers is more in line with Voltaire, who said “I was never ruined but twice — once when I lost a lawsuit, and once when I won one.” To make matters worse, unlike Voltaire, I was ruined way more than twice and, according to my lawyers, I never lost!

Yves, thank you for this analysis. The war against lawyers goes all the way back to Shakespeare’s time (and probably before). “First thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” http://www.nytimes.com/1990/06/17/nyregion/l-kill-the-lawyers-a-line-misinterpreted-599990.html Shakespeare understood that the best lawyers represent the interests of ordinary people and enforce the rule of law, without which our society descends into chaos. In my experience (32 years as an attorney), people love to hate lawyers until they need one, then they want the biggest baddest one they can find.

That is a common misinterpretation of Shakespeare! The “kill all the lawyers” remark was stated by people planning a coup. Hence lawyers were seen as a critical defense of the rule of law. For instance:

In reference to the review of ”Guilty Conscience,” (May 20) Leah D. Frank is inaccurate when she states that when Shakespeare had one of his characters state ”Let’s kill all the lawyers,” it was the corrupt, unethical lawyers he was referring to. Shakespeare’s exact line ”The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers,” was stated by Dick the Butcher in ”Henry VI,” Part II, act IV, Scene II, Line 73. Dick the Butcher was a follower of the rebel Jack Cade, who thought that if he disturbed law and order, he could become king. Shakespeare meant it as a compliment to attorneys and judges who instill justice in society.

http://www.nytimes.com/1990/06/17/nyregion/l-kill-the-lawyers-a-line-misinterpreted-599990.html

Nothing like being sued to bankrupt you. Even if you’re in the right, you can’t afford to defend yourself, while the other party’s lawyer’s on contingency. The pressure is to mediate and settle, or keep paying $250-$400 per hour, billable by the minute in minimum 15 minute blocks. Of course you settle. There’s a nastier word for the whole thing: extortion.

$250-400/hr?? Paying for Biglaw litigators is a huge ripoff most of the time, imo. Unless you have a lawsuit that will take reams upon reams of paper to defend (i.e. you are a major corporation and so are the people suing you) you will get the exact same representation and probably more individual attention from someone charging you $50-100/hr, or a graduated flat fee ($ if we settle before trial, $$$ if trial, $$$$ if appeal.) I’ve also noted a distressing tendency among Biglaw types to want to keep a case going so they can say they won a lawsuit, rather than consider what’s in the best interests of the client…

$50-$100/hr???!!!! In California???? No possible way. No way at all. Believe me, big law firm lawyers fees are way higher than what I’ve posted.

$350 an hour is the rate in CA for a not very experienced lawyer.

Big firm partners in CA are $650 an hour and more.

I can believe $350/hr for a not very experienced lawyer at a large law firm, or for high level M&E or something, sure, but for Joe’s Bait Shop being sued by a slip and fall customer? No way. The Law Office of Bill, Fred, and Sandy must exist in CA as well as MA. And they don’t charge anything like that much.

That may be true in the hinterlands — California’a a big state. But in and between the coastal megalopolises, your idea of fees are way way out of whack. Besides, you don’t even need a lawyer in a slip-and-fall — that’s a straight-up insurance liability claim, and the insurance companies pay because it’s cheaper than fighting, regardless of the circumstances. But if you have a contract dispute, forget it. Or you’re sued for something you don’t have insurance coverage for, forget it. You have no choice but to settle.

Sorry, not all that experienced solo practitioners in the Bay Area (and offices NOT in San Francisco, so you are not paying for that level of rent) are $350 an hour.

$650 is the low hourly rate for a top partner in a big law firm. Many earn much more than that per hour.

Agree that $350 per hour is pretty standard for more “mundane” work in a smaller firm, such as developing estate instruments, like trusts and wills, for example. I’m speaking about smaller cities, as well as the larger cities. Might be different in rural Ca.

I think it’s worth noting that in the US system of political economy, ‘number of people with a JD’ and ‘access to legal representation’ are unrelated issues.

Lawyers are a drag on the economy. Because what we have lawyers do in practice is ridiculous triviality in intellectual property and recreational drugs and so forth. Much of the legal profession isn’t even about litigation; trial advocacy is a minor field compared to all the corporate stuff that happens outside of court. And we funnel workers through a predatory, rent-extracting system of higher education first. You can’t even sit for a state bar exam without a piece of paper from an officially sanctioned organization. That’s called a cartel in plainer terms.

Most lawyers want desperately to do something meaningful. This is one of the biggest reasons why people go to law school. But our society doesn’t pay people to represent the voiceless and disadvantaged among us. That would defeat the whole purpose of a class-based society…

You make very good points, and I can’t argue with them. True.

America needs more lawyers. Oh jeez, how provocative. What a bunch of oblative rambling. Lemme guess, NC’s core audience are a bunch of bureaucrats in Washington.

I have a love-hate relationship with this site.

When the crypto-economy gets rolling this title will be more surreal than provocative.

First I laughed because you used the word “oblative”. Then I gagged because you tried to shove your computer coin down my throat. I know I’m a sheeple and all, but yet logic holds that just because you *want* something to happen doesn’t mean that it *will* happen.

Turn on, tune in, drop out, mate. Blockchain technology is for real.

I’m sure it is. That doesn’t render it any comparative advantage over, like, the dollar. (if anything, I believe there’s some tariff regarding exchange to hard currencies, though i could be wrong). The primary advantage of bitcoin seems to me that it’s cathectic of a particular ideology (libertarianism? church of zero-hedge? i dunno). nothing wrong with that — people should have some “skin” to back up their beliefs — but i still don’t see a non-apocalyptic scenario in which a “crypto-economy” arises…

but who knows

http://bitcoinism.blogspot.com/2013/12/lex-cryptographia.html

How about clarifying to: “We need more public interest lawyers but less corporate lawyers” or even better “We need more public interest lawyers and the requisite support so they can make a decent living (or at least pay back their law school debt) and less corporate lawyers”

As someone commented above, the govt is not required to provide public interest lawyers for civil matters. That’s the crux of the issue.

The article discusses the gradual declining funding of legal aid beginning in the 1990s. The notion is that citizens should be able to pay for their own civil matters, or simply not engage them if they can’t afford to pay for an attorney. That’s a really skewed way to view the situation, but many citizens don’t want to see their taxes going to legal aid for the usual reasons (eg, some lazy poor person is getting something for nothing, basically).

As others (and I) have commented, many attorneys would be happy to work for the govt representing citizens in matters like foreclosures, bankruptcy and even family law (which is a very difficult area of law in which to work; very stressful). We, the taxpayer, sat back and witnessed those on Wall St & in the Banks who caused the crash not only not have consequences for their crimes, but we get to witness them getting gargantuan pay raises, huge bonuses and having their tushies kissed by their patrons in the 1%.

When John & Jane Doe face foreclosure, they’re yelled at and told it’s “all their fault,” and that they should be ashamed of themselves, etc. And of course, no way for them to hire an attorney to work with them to save their homes from the predators.

Those of us who have worked in certain sectors of the legal profession are well aware of the disparities and inequalities that exist for more citizens in terms of true representation in the legal system. It is what it is.

There’s more than enough attorneys, but they shouldn’t be loaded down with humongous student debt to gain their undergrad and law degrees. And there should be the means for them to serve the needs of the citizens without having to starve, themselves.

Won’t hold my breath to see any changes.

Well, how about we import 1 million Indian lawyers on H1-B visas? When we faced nursing shortages and nursing strikes in the 80s, we opened up immigration from the Philippines for nursesIn the 2000s, after Y2K, when CFOs across the country were complaining about IT costs, we opened up 1 million H1-B visas to tech workers and lowered wages all across the IT sector. It worked for tech in the 2000s — lowered wages across the IT sector. After all, the Indian legal system is built upon Anglo-Saxon law, just as ours is. Surely if a Filipina nurse can pass the state nursing boards, an Indian lawyer can study and pass a state bar exam. I don’t see any problem with this idea at all. Though I’m very very sure the ABA would.

I hope you’re kidding, but in case you’re not…

1. You cannot take most/all bar exams unless you have a JD from a US law school. Those Indian attorneys would have to pay the usual gargantuan costs to get a law school degree here. Doubt that they’d be willing to work for peanuts with all that student loan debt facing them.

2. Even if one forces the substantial lowering of US lawyer salaries, the people who need the most help would still be unable to pay enough for lawyers to make a living. IOW: lowering wages across the board in the legal community wouldn’t solve the current problems, as discussed.

First off, we need more judicial resources and more judicial accountability.

Yves …

It seems like Paul Craig Roberts in on a similar tear to you here today.

America’s Corrupt Institutions: When the Law Goes, Everything Goes

http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/08/28/americas-corrupt-institutions/

I attended a California continuing legal education course for suddenly displaced attorneys a couple of years ago. As I recall, the presenter told California attorneys that, if they planned to open a law office and started a solo practice, they should expect to run practice for two-and-a-half years before they would be in a position to take any money out of it.

Interesting idea – but the problem with the notion that there is a dearth of lawyers in the US has nothing to do with number of lawyers. It has to do with access.

I fail to see how having more lawyers in any way improves access – as the numbers of doctors in the US is similarly not correlated with the access to heath care.

A huge fail IMO – albeit a valiant attempt to justify a (justly) vilified profession.

And as a note: I don’t think all lawyers are bad.

The problem is, the bad ones are not weeded out by the good ones.

How does number not relate to access? The more providers, the more competition, the lower the price. That is one of the reasons professions restrict entry, by requiring certain credentials which has the effect of creating barriers to entry and thus giving the incumbents more pricing power. Of course, you do have issues of specialization and location that create numerous markets for attorneys, as opposed to a single market.

And as for bad providers staying in business, how is that different from other real professions (accounting and medicine) and profession wanna-bes (consulting)?

Yves,

Numbers don’t relate to access precisely in the example I posted: The US does not suffer in any way from a dearth of doctors, yet the US has the poorest access to health care of any 1st world nation.

As for your examples on staying in business: accounting and medicine have the means of validating performance and capability.

Consulting is more similar to the legal professional – except in that case, there is even less barrier to entry. It is a great example, however: for every consultant who brings value, there are myriads who are simply better marketers.

Be that as it may – you did not address my point: there are unquestionably large numbers of lawyers who are not a credit to their profession. There are very few ways by which lawyers can lose their license to practice, and the ways which do exist consist of getting criminally convicted (by another lawyer). Nor does the supervisory body of the legal profession: the bar seem to do much to police lawyer behavior – although I’ll freely confess that I don’t know this for a fact.

Net net – the basic premise of the article: that there needs to be better understanding, compliance, and enforcement/reinforcement of legal rights – I would agree with that. That this would be accomplished by having more lawyers – I disagree.

We still have all sorts of regulatory agencies and authorities whom are NOT lawyers; the failures we see are more to do with these bodies’ regulatory capture than some lack of lawyer vigilantism in the general populace. To me, that’s one of the larger points of having government.

I don’t know who you are talking about when you say “here are unquestionably large numbers of lawyers who are not a credit to their profession.” Seriously? Class action attorneys, who are the ones most commonly demonized, in fact provide an extremely valuable service in acting as bounty hunters to police corporate abuses that are too costly for wronged individuals to pursue.

And contrary to your contention, there is in fact a shortage of primary care physicians in the US.

You clearly don’t understand accounting or medicine if you say they can be objectively measured. Accounting is in fact pretty malleable (have you not heard of the concepts like expense and revenue recognition, or quality of earnings?) and accountants often serve as liability shields for corporations by letting CEOs say “The accountant said it was OK.” Go read Francine McKenna. She discusses numerous cases where accountants were active enablers of corporate misconduct. And under the doctrine of secondary liability, shareholders can’t sue them. Only their client, the company that was delighted that they signed off on improper conduct, can.

Your argument re regulators is a straw man and is one I did not make, so so much for you engaging in argumentation. But I’ll take you up anyhow as a matter of sport. In fact, parsing case law is complicated. When a non-lawyer is appointed to head an agency whose primary job is statutory enforcement (like the SEC or FDA, the standards are different for prudential regulators, meaning bank regulators) it is widely understood in DC that that appointment is weak and was chosen because it was a presumed pushover or crony.

As this conversation continues, it becomes increasingly evident you are arguing based on personal prejudice rather than any evidence.

The problem is that competition cannot lower prices below the break even point for the lawyer. Nobody is going to lower prices to below their costs just to be competitive. Instead they drop out. So when high tuitions, high rents, and high regulatory costs (bar dues, CLEs, etc) combine you get high reserve prices for lawyers, and they just drop out of the profession if they can’t make enough to make a reasonable living.

There are too many lawyers because turning law students into lawyers is very profitable for schools. But the high tuitions are just one of the costs contributing to high prices for lawyers, such as rents, insurance, etc.

McKinsey which I would argue has a better brand name than all but the very very most elite law firms (and better board room access than any) in fact dropped its rates massively during the dot com bust, when there was a tremendous oversupply of consultants (McKinsey cut its staffing in North America by 50% in a two year period).

It was literally giving away studies as teasers in the hope of getting more work

Brand name professionals are not immune to supply and demand, but they are better protected by virtue of creating a niche that is generally resistant to entry (as in more supply).

I think this may be asking the wrong question. It isn’t a matter of whether there are enough attorneys, or not. Instead, it should be about whether a legal education needs to be made more widely available.

I believe strongly that law should be an undergraduate program and certain courses can be taught effectively in community colleges. The skills taught law school are mostly about critical thinking and, if you ask me, often common sense. If more people have a base understanding of law, the kind you get from the first year of law school, then I think we’d have a more engaged society and valuable work force.

I graduated law school during the financial crisis and, although licensed, don’t practice law. My legal training comes in handy everyday at work and in my personal life.

Reducing the cost of legal services for the poor can in theory be done in two ways:

1. Increase the supply of lawyers. The increased supply with unchanged demand should in theory drive down the price. It has been tried (as per quite a few posts above) and it hasn’t worked.

2. Decrease the demand of legal services. The decrease of demand with unchanged supply should in theory drive down the price. Decreased complexity should in theory decrease the amount of billable hours (demand). Lawyers argue that the current system has exactly the right amount of complexity (or even that it isn’t complex enough). It hasn’t been tried in practice in the US, we don’t know if it would work or not in the US.

The fallacy of the argument for more lawyers is obvious: we’ve already produced record numbers of lawyers, and never have legal occupations represented a larger part of our workforce, or a larger proportion of total remuneration received. Yet all during that time of record-breaking levels of lawyering, our society has become more and more obviously unjust.

The fallacy is also obvious when we look at the problem from another direction: is our vision of a fairer society one in which we produce many more lawyers to assist citizens in all their affairs?

The perceived need for even more lawyers indicates that our problem is chronic and structural.

Relaxtion of narcotics laws would drastically reduce the need for all kinds of criminal lawyering and judging needed in our society.