Yves here. We posted yesterday on how, despite falling oil prices having a ricochet effect across the entire energy complex, so far shale oil well shutdowns didn’t appear to be proceeding at the expected pace. John Dizard of the Financial Times attributed continuing cash-flow-negative exploration and development to continued access to super-cheap funding. He also noted that even when fracking operators were cut off from their money pipeline, a new wave of speculators was likely to sweep in and try bottom-fishing among distressed companies. That meant that normal market discipline would be circumvented, meaning production levels could remain at uneconomically high levels, keeping prices low.

A second danger for the aspiring fracking-industrial complex is that prevailing production forecasts show the US having production well in excess of its domestic consumption levels in a few years. Production of needed export infrastructure would need to ramp up rapidly for so much shale output to be moved overseas. But not only are there “will the transport systems be in place” doubts, there’s also a reason to question whether this investment will pay off. On current trajectories, fracking output peaks in 2020 and falls gradually over the next decade, and declines more rapidly after that. 12 to 15 years of decent utilization is very short for specialized facilities.

Third, some readers, presented with the scenario above, said, basically, “No problem, production will focus on the lowest-cost areas like Marcellus.” As the article below points out, there are parts of the country that have gotten a nice boost from the energy boomlet and will suffer if they aren’t in the most competitive areas cost-wise. And their lenders are also at risk.

Finally, current cost forecasts don’t allow for the possibility of production delays or additions expenditures due to local protests and/or higher environmental standards put in place. Before you pooh-pooh the idea that anything might stand in the way of energy barons, consider the industry they are damaging: real estate, which is another powerful and politically connected industry. If fracking water contamination or fracking-induced earthquakes start affecting higher population density areas (suburbs, cities), we may have a Godzilla versus Mothra battle between competing elites in our future.

By Steve Horn, a freelance investigative journalist and past reporter and researcher at the Center for Media and Democracy. Originally published at DeSmogBlog

Outgoing Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC) chairman Phil Bryant — Mississippi’s Republican Governor — started his farewell address with a college football joke at IOGCC‘s recent annual conference in Columbus, Ohio.

“As you know, I love SEC football. Number one in the nation Mississippi State, number three in the nation Ole Miss, got a lot of energy behind those two teams,” Bryant said in opening his October 21 speech. “I try to go to a lot of ball games. It’s a tough job, but somebody’s gotta do it and somebody’s gotta be there.”

Seconds later, things got more serious, as Bryant spoke to an audience of oil and gas industry executives and lobbyists, as well as state-level regulators.

At the industry-sponsored convening, which I attended on behalf of DeSmogBlog, it was hard to tell the difference between industry lobbyists and regulators. The more money pledged by corporations, the more lobbyists invited into IOGCC‘s meeting.

Perhaps this is why Bryant framed his presentation around “where we are headed as an industry,” even though officially a statesman and not an industrialist, before turning to his more stern remarks.

“I know it’s a mixed blessing, but if you look at some of the pumps in Mississippi, gasoline is about $2.68 and people are amazed that it’s below $3 per gallon,” he said.

“And it’s a good thing for industry, it’s a good thing for truckers, it’s a good thing for those who move goods and services and products across the waters and across the lands and we’re excited about where that’s headed.”

Bryant then discussed the flip side of the “mixed blessing” coin.

“Of course the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale has a little problem with that, so as with most things in life, it’s a give and take,” Bryant stated. “It’s very good at one point and it’s helping a lot of people, but on the other side there’s a part of me that goes, ‘Darn! I hate that oil’s dropping, I hate that it’s going down.’ I don’t say that out-loud, but just to those in this room.”

Tuscaloosa Marine Shale’s “little problem” reflects a big problem the oil and gas industry faces — particularly smaller operators involved with hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) — going forward.

That is, fracking is expensive and relies on a high global price of oil. A plummeting price of oil could portend the plummetting of many smaller oil and gas companies, particularly those of the sort operating in the Tuscaloosa Marine.

Tuscaloosa and Oil Price

Governor Bryant’s fears about the price of oil are far from unfounded, serving as a rare moment of frank honesty from Mississippi’s chief statesman.

As discussed in Post Carbon Institute‘s recent report, “Drilling Deeper: A Reality Check on U.S. Government Forecasts for a Lasting Tight Oil & Shale Gas Boom,” the fracking industry relies on high oil prices to stay on the drilling treadmill and keep shale fields from going into terminal decline. Further, future projections of shale gas and oil fields are wildly over-inflated, argues the Post Carbon report.

“Other factors that could limit production are public pushback as a result of health and environmental concerns, and capital constraints that could result from lower oil or gas prices or higher interest rates,” reads a passage in the Post Carbon report. “As such factors have not been included in this analysis, the findings of this report represent a ‘best case’ scenario for market, capital, and political conditions.”

Recent articles published in the business press further highlight the key caveat in the Post Carbon report, as did a recent Halcón Resources Corp investor call that discussed the Tuscaloosa Marine.

“Tuscaloosa Marine Shale, I’m going to do my darndest to make sure that people understand that we’re highly confident and we like the play,” Halcón Resources CEO Floyd Wilson said on the call.

“However, it is currently a relatively high-cost play and with currently low crude prices we will not be devoting a significant portion of our resources to TMS in the near term,” Wilson continued. “Having said that the TMS is certainly more susceptible to low oil prices than our other crude plays due to the higher well costs, a tempered approach to drilling in this play in the near term is warranted.”

A recent report published by energy investment firm Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co., described Tuscaloosa Marine as the shale basin most likely to face severe impacts from the falling price of oil. The Tudor report said that drillers operating in the Tuscaloosa require oil to sell at $70-$90 per barrel for fracking to remain economically viable there.

The $80 Mark

Mississippi does not stand alone in feeling the hurt associated with a drop in the global oil trading price.

Bloomberg reported that companies operating in Utah and Texas have already slowed down drilling as a result of the high oil prices they had previously relied upon. In total, 19 U.S. shale plays will no longer be profitable if the price of oil continues to fall.

“Everybody is trying to put a very happy spin on their ability to weather $80 oil, but a lot of that is just smoke,” Dan Dicker, president of MercBloc, said in an interview with Bloomberg. “The shale revolution doesn’t work at $80, period.”

Not all industry insiders, however, are trying to spin things.

Ralph Eads, a life-long friend of former Chesapeake Energy CEO Aubrey McClendon and global head of energy investment banking at Jefferies LLC, agrees with Dicker’s assessment.

“If prices go to $80 or lower, which I think is possible, then we are going to see a reduction in drilling activity,” Eads told Bloomberg. “It will be uncharted territory.”

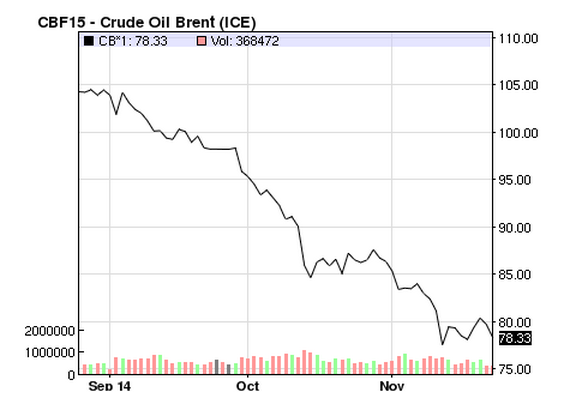

As of November 25, 2014, the price of Brent oil has fallen to $78.33.

Image Credit: Nasdaq

A Wall Street Journal article from late October concurred with others who said the Tuscaloosa will take a beating with the fall of the price of oil. But it also concluded that for operators in many other more prolific shale basins like the Bakken Shale and Eagle Ford Shale, $60 per barrel is the break even point, not $80.

One Mississippi, Two Mississippi…

To the smaller companies operating in the Tuscaloosa, recent oil pricing developments are likely no laughing matter.

But that didn’t stop Governor Bryant from cracking a joke to conclude his presentation at the IOGCC annual meeting.

Image Credit: Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission

“Fraser Institute says Mississippi is the second in the world for oil and gas development…so we came up with this little idea,” Bryant joked. “We have the number one and number three football teams in the nation: one Mississippi, two Mississippi, three Mississippi. That used to be a call signal for how long you could take before you could rush the quarterback.”

But as with all numbers, it depends on who’s counting. And the Fraser Institute is an associate member of the industry-funded State Policy Network “stink tanks.”

As with shale gas production numbers and figures, it always pays to consider the source.

“US having production well in excess of its domestic consumption levels in a few years.”

That’s not going to happen, that would mean another 10mbd. Even EIA looks at things starting to peter out by 2020 and they’re always optimistic. This has got another couple years at most before starts decline, the interesting thing will be if before declines set in if we’re able to tell who if anyone actually made money on this thing. One thing for sure, its a lot less people at $75 than it was at $100.

The FT has a source that disagrees with you and they are referring to production levels by 2019:

So much gas is being developed in the Marcellus and Utica resources of the northeastern US that it really cannot be absorbed by the US market. Suzanne Minter, manager of oil and gas consulting at Bentek in Denver points out: “Over the next five years, daily production in the US is forecast to grow by more than 16bn cubic feet per day, with about 10bcf of that coming from the northeast. Of that, at least 8.5bcf has to be exported. Domestic demand does not grow enough.”

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/0f5be83a-717f-11e4-818e-00144feabdc0.html

Fracked fields have very high first-year production but have very sharp decline curves. The Marcellus is going to be running out by 2020. Already, all the “sweet spots” have been drilled and the undrilled areas have terrible return rates.

The Bakken is exceptional, but all the other fracked fields are set to decline very quickly.

http://www.postcarbon.org/publications/drillingdeeper/

So sure, production may be very high in 2019, but it’ll be crashing down by 2025.

note that joe is talking about oil (+10mbd) and you are talking about gas (10bcf) and to an extent i agree with you both; we’ll never produce enough oil to eliminate our imports, while our present imports of gas, mostly from canada are marginal and given higher prices we might produce enough to export; see this:

http://www.ferc.gov/market-oversight/othr-mkts/lng/ngas-ovr-lng-wld-pr-est.pdf

also note that gas prices might be quoted in mmBTU (million BTU) or Mcf (thousand cubic feet) and that they’re roughly the equivalent amount of gas…

Maam;

It’s taken me a while to respond to your querry from another thread about my idea concerning LNG production and export because I’ve been otherwise engaged. In reply, no, I do not have specialized expertise in the field. I really am a plumber. However, one of my sons in law works in a field related to the design of petrochemical sea transport, and has engaged me in much lively discussion about it. (When he talks about his field of expertise, I shut up and listen. He knows what he’s speaking about.) One big item affecting petrochemical shipping he taught me was the cost and length of time it takes to build, and then pay off one of those behemoths. They aren’t cheap. It takes major financing to build a tanker. Tankers are usually pre leased for several years before the keel is even laid. To guarantee financing and utilization, long term supply contracts are often needed. The Bloomberg article linked to below gave the overall figure of $186 million per year this year in U.S. Government subsidies for U.S. flagged and manned cargo vessels. This is the result of the Jones Act which requires inter-state shipping to be in U.S. flagged bottoms. One fascinating fact given was that gasoline was $.15 more expensive in some parts of the U.S. due to a shortage of U.S. flagged tanker capacity to transport petrochemicals within the United States. Do read the last section of the Bloomberg article. In it, the author stated that the U.S. Northeast was buying LNG from Europe at a premium because there are no U.S. flagged LNG tankers to handle domestic LNG transport from Texas to the Northeast! It looks like the Jones Act is going to become a political football soon.

The other bottleneck in LNG supply is liquefaction capacity. I know from personal experience in commercial construction, and from watching my Dad oversee construction and refitting of sugar mills in the Sixties, that industrial plant is expensive and time consuming to construct. One basic point is that the supply of raw materials and the demand for finished product have to both be in place before anyone will make such an expensive venture. A decent series of “user friendly” short pieces I stumbled across is linked to below. (It is written in a series of short articles, so keep scrolling down for new subjects.)

All of the above ties intimately in with the expected time lines for shale gas supply. Oil wells usually produce some gas along with crude. This has always been a part of the oil and gas business. So, any major increase in gas exporting would be tied to increases in the spread between LNG costs at the dock and end users prices. Japan is the biggest importer of LNG. The price of domestic energy production in Japan is now decoupling from Atomic electric production for obvious reasons. Having few natural resources of their own, they fought a big war last century over that, Japan relies on imported hydrocarbons. Until Green Energy takes off, this should continue into the future. China and India both are expanding their reliance on imported hydrocarbons as their populations and economies grow. China has shown itself to be fully invested in Green technology development for national security reasons. India should not be far behind. Both are essentially rational states who have an understandable reluctance to be beholden on foreign governments for such a basic item. So, those governments’ policies concerning energy supply and independence will affect hydrocarbon trading around our globe.

Thank you for your patience.

Bloomberg: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-03-07/us-flaged-lng-ships-gain-support-as-export-costs-seen-rising.html

Market Realist: http://marketrealist.com/2014/05/working-overview-of-investing-in-lng-carriers-future-of-natural-gas/

The northeast buys cargoes from abroad b/c there is no liquefaction capability in the US, it has nothing to do with the Jones act currently. That may come into play when the US brings liquefaction plants on line, but for now it’s not an issue. The Jones act will come into play when Repsol tries to optimize their receipts of gas in the future, but the evolving natural gas pipeline grid may render that irrelevant.

Given the Billions of dollars needed to bring a LNG facility (import or export) online, they all have long term contracts to back financing. Funny thing is the US just got done building many import facilities, and except for the NE/Canadian plant, none of them are doing anything b/c US gas is so cheap. Now they are turning some of them around, and it’s an amazing use (waste really) of dollars.

i dont know what “the expected pace” shale oil well shutdowns should be proceeding at, but i’m satisfied that it’s progressing…as i wrote two weeks ago: with low prices for oil persisting, there have been more signs of a slowdown in fracking activity among the companies with an oil patch focus… companies from Continental Resources, a major driller in the Bakken, to Pioneer Natural Resources, with holdings in the Eagle Ford Shale, have reported to shareholders that they’re cutting back on spending and will be drilling less in the coming year…the Financial Times reports that Halcon Resources, Rosetta Resources, Conoco Phillips, Devon Energy, EOG Resources, and Hess will similarly be cutting back on their capital spending plans, although others, such as Occidental, will wait till the end of the 4th quarter to lay out 2015 plans…meanwhile, the pullback in North Dakota has been so pronounced that state legislators are already considering that they’ll have to factor the possibility of lower royalty payments when drawing up the coming year’s budget; the WSJ notes that although the break-even price for oil in North Dakota is about $35 a barrel, 15% of the production in the state has a break-even price above $87…low oil prices are having similar impact on other drilling as well; Transocean, who you’ll recall was the owner of the Deepwater Horizon, who plead guilty for their involvement in the BP Gulf oil spill, reports that they’ll be taking a $2.8 billion write off for the 3rd quarter, primarily because their 29 deepwater drilling rigs had accumulated 296 combined days of being out of service in the third quarter, and that they further expect 435 days of idle deepwater drilling rigs in the 4th quarter…

most of that is from 3rd quarter reports…

then four days ago i added:

after weeks of anecdotal stories about drillers cutting back on activity, this week’s economic data provided the first hard evidence that it’s actually been occurring…the Fed’s G17 release on Industrial production and Capacity Utilization for October showed that US industrial production fell slightly, primarily because production from the “mining” sector, which includes gas & oil production, fell .9% for the month, while the oil & gas extraction component of that fell 1.1%, the kind of drop not usually seen unless weather disrupts drilling in the Gulf…the associated drop in capacity utilization, which is the percentage oil & gas drilling equipment that was in use during the month, was even more pronounced; from an operating rate of 98.9975% in September, equipment utilization for gas and oil drillers fell to 96.7865% in October, a drop of 2.2% in the percentage of gas & oil well drilling equipment that was in use, which probably means they had ordered new equipment earlier this year only to idle it when it was delivered…admittedly, one month’s data doesnt prove a lot, especially in light of the growth the industry has seen over recent years, but we’re already well through November without a change in the downward trajectory of oil prices, so if that continues, we may see a contraction in the industry in the coming year at least as great as the recent expansion…

as i said, i dont know how fast you’d expect the industry to shut down..it took decades to kill domestic steel…

Oil storage is very limited, and I suspect gas even more so, so it is stored in the ground, as in not “lifted” when prices are unfavorable. So not dialing back production pretty quickly is not typical behavior.

a 1.1% drop in actual production in October seems like quite a drop to me…prices didnt seriously break below $100 until September, and any wells being drilled at that time would have been finished, while producing wells extant then would continue to produce…assuming a ~40% annual depletion rate in shale, for output to drop over 1% in October, it suggests that new drilling would have been cut by nearly a third in a months time..

I had originally thought that shutdowns were happening pretty promptly. Dizard at the FT suggests they aren’t, or at least not to the degree you’d expect. So we have divergent readings.

Recall that many of these companies are in the land-flipping business. They must report high production numbers in order to flip their wells to sucker buyers.

The idea that gas export facilities won’t get built due to investor payback concerns – I.e. investment fundamentals – is probably wishful thinking.

When is the last time fundamentals got in the way of a good bubble?

I think we can fully expect the government to help lower the cost, and the cost of financing the infrastructure. And guarantee the investments for good measure.

The march of folly continues.

Third, some readers, presented with the scenario above, said, basically, “No problem, production will focus on the lowest-cost areas like Marcellus.”

I assume this is in response to my comment yesterday … FYI I was talking specifically about dry gas, in contrast to oil / liquids. I think it’s really worth treating the two markets completely separately, even though the production technique is the same.

Focusing on lower-cost areas, in both markets — That is present tense, not future (see link below). Examining the payback on the stock of existing wells (drilled in the past 4-5 years lets say) is important, but is essentially a rear-view-mirror analysis, at least as far as drawing conclusions about near term future prices/production on a national level. What happens to the investors, lenders, landowners, suppliers, local governments and communities, and everyone else involved in the process — that’s a whole another story of course.

http://phx.corporate-ir.net/External.File?item=UGFyZW50SUQ9NTYyMDI5fENoaWxkSUQ9MjYxNTQxfFR5cGU9MQ==&t=1

When gas prices went south in late 2000s, a lot of the Piceanse gas drillers picked up their operations and headed over to the Bakken to drill oil instead. The national average of drilling activity disguised the net loss in one region/product moving to a different region/product.

Peteybee, good stuff again. The blog post above is drowning in misunderstanding and ignorance. Will look out for more of your posts on energy.

From what I know the Tuscaloosa Marine is too soft for conventional fracking. The shale closes over the propant, forcing larger amounts of propant to be used. The Eaglebine was deposited in a deltaic environment and the amount of sand cuts down on the organic content of the shale. But if I remember correctly it is a combo of the Woodbine and Eagle Ford.

Every “shale” formation is unique. In fact, many are not shales. I would say the Eagle Ford is closer to a marl and the Niobrara seems to be a stacked play, somewhat, of alternating marl and chalk units. The Bakken is actually a sandy dolostone laying between two shale units.

And there are many reasons there has been no sudden pull back in production. One, remember that these companies hedge their sales. Second, wells can take years to drill and complete. In fact, it may take six months to a year or more to complete a well (frack plus connect to pipeline). Third, drilling activity (not rig count) can and does slow down due to the winter weather. It snows in many parts of the Marcellus and parts of North Dakota see severe cold temperatures and snow. Fourth, these operators (the oil companies) are locked into contracts with their drillers.

If this decline in prices is temporary, less than nine months, then there is no use in a company getting their panties in a wad.

So, as for earthquakes in major cities: haven’t heard a peep from Dallas or Fort Worth where shale gas drilling has been ongoing for a decade.

Toxic waste injection wells are what cause the earthquakes. It’s becoming a big issue in Ohio.

in Ohio, we have had quakes caused by multiple-lateral fracking, and that’s the reason the ODNR initiated the regulations mandating seismic monitoring…

here’s some good documentation on how fracking caused the Poland Ohio quakes: http://www.nofrackingway.us/2014/03/10/ohios-first-frackquake/