The Maryland Policy Institute issued a report this summer on the impact of high fee strategies on public pension fund returns. The results are devastating as far as high-fee strategies, both alternative investments like hedge funds, infrastructure funds, and private equity are concerned, as well as active managers. Needless to say, followers of John Bogle would not be surprised, but a horde of pension consultants have apparently succeeded in persuading public pension fund staff and trustees that they can find someone with a hot hand who can deliver them sparking performance…if they are willing to ante up for it.*

I’ve embedded the short, tartly worded paper at the end of the post and urge you to read it in full. It shows the high cost of investing in high fee strategies:

The study also shows that a passive index that mimics the investment allocation of the typical state pension fund outperformed the peer group median by 1.62 percent per year over a five-year period. On an initial $50 billion pension fund, this difference over five years is equivalent to $6.8 billion in foregone income.

The same team performed the same analysis two years ago and got similar results.

Note that this study analyzes only the fees reported in public pension funds’ Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports. That means that both the return and even more so, the fee data is less than complete. We’ll turn to the problems with the returns as far as private equity is concerned shortly and will discuss fees first.

On the fee side, as the fiascoes in recent CalPERS’ Investment Committee meetings have demonstrated, CalPERS, like most of its peers, does not include the profit share mislabeled as “carry fees” in its Comprehensive Annual Financial Report. And it does not report the full management fees in the private equity fees and costs section of its CAFR. It includes only the hard dollar payments, and omits the portion shifted onto portfolio companies via management fee offsets.

And as we wrote earlier this year, standard-setter CEM Benchmarking concluded that virtually all public pension fund expense reporting was out of compliance with applicable accounting standards. From a May post:

CEM also points out that most public pension funds are not complying with government accounting standards in how they report private equity fees and costs, and that based on their benchmaring efforts with the South Carolina Retirement System Investment Commission and foreign investors, most public pension funds are missing at least half of the total costs.

Ex-banker, now private equity researcher Peter Morris confirmed that sorry picture in a quick and dirty look at 15 pension funds. From his draft analysis:

– Two (small) funds disclose both management and performance fees for PE (South Carolina and a smaller Texas fund)

– Nine disclose management fees only (with no mention of portfolio company fees)

– Three fail to break out PE from overall expenses

– Only CalSTRS fails to report even management fees on PE. Until last year it was trying to avoid admitting that it had failed to report the data. As of 2014, it at least comes clean about not reporting even PE management fees. It doesn’t say why it doesn’t report them. The most obvious explanation would be that it simply doesn’t have the data.

Remember that CalSTRS is the second-biggest public pension fund investor in private equity. And here’s an example from CalPERS of how IRR provides misleading results. The first fund in its latest private equity performance report is 57 Stars. It reports an 8.3% IRR but has only returned 20% over its 6-7year life. As one observer said, “At best 3.3% a year ignoring compounding.”

Even worse, that 8.3% IRR is almost certain to be reduced in future years. Since PE funds that do well tend to return most of the capital invested early, it’s almost certain that when 57 Stars eventually liquidates its investments, some, and probably most, will be sold at a discount to their current reported values, with persuasive-sounding explanations as to why it made sense to sell at a discount to what they were supposedly worth (that is typical behavior when dealing with portfolio companies that are clearly at a point where they should have been sold already but are still in the fund).

The reason for underscoring the magnitude of fees that are simply ignored in private equity is the fee gouging is directly related to the lackluster performance. As Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou said via e-mail:

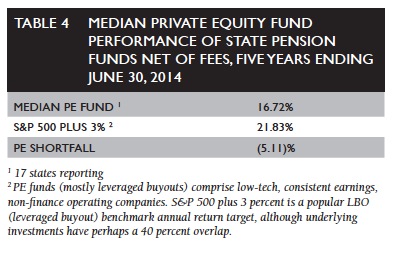

A responsible consultant would take the return evidence seriously and would have also computed the fee bill. The evidence is loud and clear:

Average PE gross of fees returns = 20%

Average PE net of fees returns = 12%

Average listed stock returns = 12%Instead of arguing to change the benchmark to 3% and go home, why aren’t investors and consultants tackling what seems to be the real issue here!

But even then Phailppou is giving private equity the benefit of the doubt on the investment return side. Private equity does not outpeform when properly measured. Astonishingly, the industry has gotten investors to accept bogus return metrics.

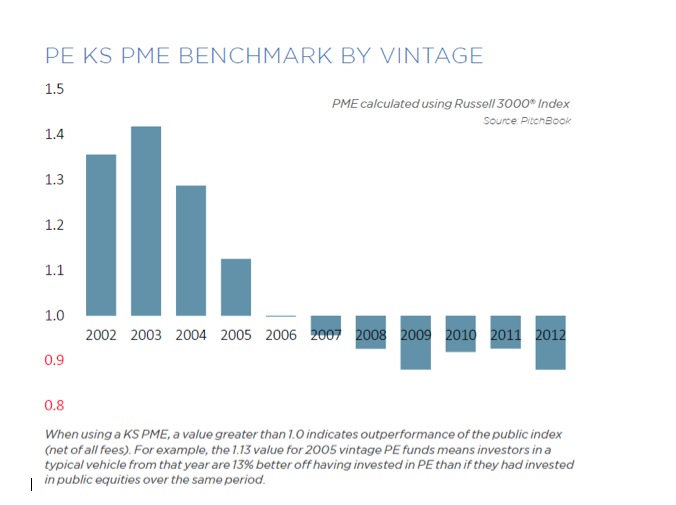

Private equity uses IRR, meaning comparisons with public equity benchmarks are a garbage in, garbage out exercise skewed to favor private equity. McKinsey has criticized the use of IRR for calculating investment returns: “…typical IRR calculations build in reinvestment assumptions that make bad projects look better and good ones look great.” That is particularly true for private equity, since IRR is particularly flattering for investments where high returns are realized early on and doggier ones later. Using public market equivalent, which is an apples to apples comparison, produces a very different picture:

As Eileen Applebaum, the co-author of Private Equity at Work, said in an e-mail:

PitchBook’s calculation of the PME and IRR for median PE funds of various vintages stops with 2012 vintage since more recent vintages still have few exits and lots of dry powder, making estimates of performance problematic. Very different results for PME and IRR. IRR exaggerates performance.

Private equity uses valuations that are known to be questionable. Unlike public securities and hedge fund investments, private equity is not subject to independent valuation. That means it is rife for abuse, and there is considerable evidence that it has been abused.

In a 2013 paper, How Fair are the Valuations of Private Equity Funds?, Tim Jenkinson, Miguel Sousa, and Rüdiger Stucke concluded that private equity funds exaggerate performance around the time that they are raising funds. Since this typically occurs 4 to 5 years after the previous large fund was raised, this goosing occurs relatively early in the fund’s life. Recall that the use of IRR exaggerates the impact of early high returns, so this overstatement is made more pernicious by the use of IRR.

This study also confirmed another wide-spread criticism of private equity valuations, that they are “smoothed,” which means they understate how much the prices of portfolio companies change over time if they were value properly. This is especially noteworthy in lousy equity markets, when private equity perversely reports lower price declines than public stocks, when given their high leverage levels, it’s almost certain that (absent the occasional instance of distressed financial re-engineering, of buying back cheap debt at a discount) the price declines of portfolio companies on average would be even more severe.

This fudging of valuations helps investors like public pension funds tell extremely useful lies. The false low declines of private equity portfolio companies in down markets is treated by pension consultants as if it were real, and is used to advance the bogus claim that private equity is a useful addition because it diversifies risk. If private equity firms want to create risk-buffering exposures, they can create custom “synthetic beta” for a hell of a lot less than private equity’s “2 and 20” fee structure. Worse, the real purpose is for pension managers and overseers to present an artificially rosy picture of how the fund is doing in bear markets.

Reports of private equity “outperformance” are suspect due to sample bias and use of IRR. From Private Equity at Work:

Because there is no publicly available or comprehensive data set on private equity, all studies of performance suffer from incompleteness and biases, and different methods of calculating returns lead to different results. But some methodologies and data sets are more credible than others. Reports that PE funds substantially outperform the stock market come almost entirely from industry sources that use the internal rate of return as a measure of performance. This measure is deeply flawed, for reasons examined in this chapter, and many finance scholars reject its use. Industry reports are also biased, as they rely on the data and methods of self-interested parties.

Our review covers the most credible research by top finance scholars. They report much more modest returns to private equity funds, with some showing that the median fund does not beat the stock market and others showing that median returns are only slightly above the stock market.

The Maryland Policy Institute report was less charitable:

Furthermore, the private equity industry has yet to offer proof that private equity (PE) consistently

beats the relevant public equity market index, after fees. Recent experience suggests the reverse.

Notice that using a S&P 500 benchmark is a gimmie to private equity. Private equity portfolio companies are much smaller than the average S&P 500 companies, and smaller-company stock indices generally show higher rates of return.

The report also takes a dim view of the diversification defense for sub-par results:

When questioned about the unproven history of alternative assets, public pension funds officials and investment consultants typically respond that while performance may be mediocre, alternatives allow diversification out of public equity and public fixed-income markets. This statement

shows a lack of understanding about alternatives.Hedge funds principally invest in publicly-traded securities or example, Pershing Square hedge fund, run by Bill Ackman, has sizeable positions in Canadian Pacific (long), Herbalife (short), and Burger King (long). Private equity funds acquire mainly securities in privately owned corporations. However, the underlying issuers of such private securities have economic attributes that resemble their publicly-traded counterparts in many ways. That is hardly diversification.

The propaganda efforts of the private equity industry and its dependents, the pension consultants, have created what the Maryland Policy Institute correctly calls a Stockholm syndrome, where the incumbents seek out advice only from parties who have a vested interest in preserving a high-cost status quo that leeches pubic pension funds of returns. The taxpayers who are on the hook need to demand regime change.

____

* Mind you, that’s the most charitable interpretation. As David Sirota in particular has documented, there are plenty of incidents where investment decisions look to be tied to political back-scratching. And even where the influence is not overt, I am told that public pension employees are afraid of private equity fund general partners, in that they believe that they wield enough power in state legislatures to get them fired. Mind you, no one can point to a single example of that having ever happened, and one politically-savvy contact who has done time in private equity regards the notion as preposterous, in that any move like that would wind up being so obvious and heavy handed as to damage the firm’s position, and conceivably cause a real scandal. But the fear does not need to be well founded for it to produce the desired outcome, that of public pension fund staff aversion to challenging the logic of investing in private equity.

The Maryland Policy Report findings are understated because many plans are still hiding Private Equity fees. In the report it takes from the official financials of Kentucky $42 million in PE fees. A recent CEM analysis found this to be $160 million in fees. However Kentucky feels CEM’s numbers are too high and is reporting around $100 million a year on the financials in what they are calling a .”Proactive Transparency Change”

http://www.kentucky.com/2015/09/15/4038324_fees-paid-by-kentucky-retirement.html?rh=1

With zirp, a dwindling choice of publicly traded companies and plans looking for low risk, high return investments to fund pensions,what else could we expect?… that environment is set to attract the snake oil salesmen….

Interestingly, these posts are not those that get the most traffic when the pension system is at the root of our monetary problems thanks to an ageing population in a system shoving individualism and self-funding down our throats.

That’s a contradiction in terms, right? You earn high returns by taking on additional risk. Surely fund managers understand that…well, probably…

If you are guaranteed high returns with high risk then there is no risk!

So when one takes high risks, there is some chance of getting high returns and much higher chances of losing.

However, QE and bailouts have totally destroyed the valuation of risk and the population’s understanding of it. And now the left thinks government can fix this without a change in paradigm.

Where do pensions fit in all of this… The theory says that efficient diversification will maximize return while reducing risk. Risk in the practical context is volatility.

This is where alternatives fit in… Plan sponsors are looking for ways to reduce plan funding to reduce the impact on corporate earnings… Funds invested in assets valued with appraisals look quite attractive in that context. The amazing thing with alternatives is that it can take 5-10 years for reality to catch up (ramp up of infra projects leading to cost overruns)… So these are attractive to both perma-optimists and those looking to kick the can down the road .

In the final analysis, the pension system is a mess and probably one of the biggest contributors to the concentration of wealth.

Everyone should have had access to the same types of pensions.

In north America a lot of people have trouble understanding that the one getting 50k might have contributed more to society and the economy than the one getting paid 200k… Therefore they might deserve the same pension. Most people do not understand that the pricing system is broken at every point in the system

NC rocks. You can’t get this anywhere else.

I read a paper years ago (at the start of the LBO boom) that argued convincingly that the vast majority of the economic value “generated” by PE funds and LBOs is due to the tax-shield of leverage. Such a strategy does work for low beta (low volatility) companies and companies with very low maintenance capex. Most of these companies were picked off years ago. I think the PE universe increasingly resembles the broader market, and I remember reading a story (maybe here?) that you could replicate or even exceed the returns on a typical PE fund by buying the broader market w/ leverage. Without the fees.

PE lenders will now LBO just about any asset they can get their hands on, because the thinking is that a couple of 3-baggers in a portfolio will offset 7 or 8 turds — plus, they get their base 2%, anyway. It really does seem like a rigged game.

whoops, I meant “PE firms” not “PE lenders” at the start of paragraph 2

Thank you for your continuing coverage of the ways public pension funds get ripped off by predatory Wall Streeters and their captured fund ‘fiduciaries.’

Here’s a chart I’d love to see, forgive me if it exists and I’ve just missed it:

A State by state analysis in funding shortfall for pensions after imagining the funds hadn’t been fleeced in these ways

That is, if state pension funds had only ever been in vanilla investments, year after year, would the holes look anything like they do now? For sure chickens-t legislatures have failed to ante up in budgets when they should have, but all of the claims about how public employee pensions are grossly unaffordable look different if a material amount of the hole is due to the kind of corrupt extraction you’ve ben documenting.

Great questions and would love to see a chart created like that, if possible.

What the general public, including those either investing in or receiving money from public pensions, is how the system has, once again, been gamed/rigged by Wall ST – in this case PE – to munificently benefit themselves, whilst ripping off the 99%. Another take on privatizing the benefits and socializing the losses. All while dissing government/public service workers as the scourge of the earth. Nice job at distracting whilst fleecing the rubes.

. . . Nice job at distracting whilst fleecing the rubes.

Pirate Equity can make a lot of money on some investments. But do they share? No one will ever really know.

Thanks again for these PE posts. PE is taking state pensions to the cleaners.

A question I’ve had for a long time (and probably unanswerable) is just how unfunded the post office and public pensions really are? The post office pension was deemed sound until the accounting rules for it changed. (a new 50 year time horizon? really? guess they’ll have to sell off some prime real estate.) By the old accounting rules the post office pension is still sound. In the same fashion the accounting rules for state pensions changed in the last 15 years. Under the old rules they were sound or had a small problem. Under the new rules they were overnight dangerously underfunded and have a big problem. How much has this rule change contributed to the drive for higher rates and PE investments? One can only wonder.

No matter the answer to that question, state pensions are being taken to the cleaners by PE. State pensions ought to get out of PE.

If they get out of PE, then they’ll have to admit they might have to cut benefits…

Thanks again for the in-depth reporting on the vast rip off of PE investments by government pension funds. The sooner these big pension giants, like CalPERS, stop investing in PE, the better for us all.

Keep up the good work! I am reading this and also communicating with CA state officials about this. Something needs to change fast.

Bill Gross frames pension funds’ dilemma this way:

Regarding private equity as an ‘alternative’ to public equity is mistaken. Economically, they are the same damned thing, but with the latter being more liquid, more transparent and less leveraged than the former.

One of the few truly uncorrelated asset classes is pet rocks — you know whut I’m talkin’ about; the old yellow dog. A pension meltdown, and the inevitable equal and opposite reaction thereto by the authorities, generates the kind of monetary uncertainty which benefits metals that don’t rust in the rain.

I think you are right that the Fed has put insurance companies and pension plans in more than a pickle. They inflated asset prices on the premise that robust growth would come and ‘justify’ those prices. They forced everyone to take more risk. Oops. So now, if the long rumored ‘air pocket’ actually turns out to be real, equities (and some bonds) gap down, and pension funds and insurers get their heads handed to them.

What do we do for the insurance co and pension plan bailout? Well, I suppose insurance companies can raise rates. Pension plans? Got shantytowns?

. . . So now, if the long rumored ‘air pocket’ actually turns out to be real,

I think it will be more like a vacuum.

“Worse, the real purpose is for pension managers and overseers to prevent an artificially rosy picture of how the fund is doing in bear markets.”

You mean “present an artificially rosy picture”?

Thanks, fixed.

An official with the American Federation of Teachers, whose members are relying on pension investments, told Pando that the disclosures of huge fees and potential conflicts of interest may put pension trustees at odds with the law.