By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street

nvestors, lured into the $1.8-trillion US junk-bond minefield by the Fed’s siren call to be fleeced by Wall Street and Corporate America, are now getting bloodied as these bonds are plunging.

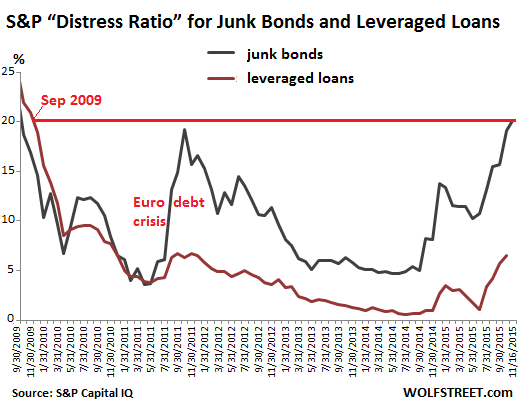

Standard & Poor’s “distress ratio” for bonds, which started rising a year ago, reached 20.1% by the end of November, up from 19.1% in October. It was its worst level since September 2009.

It engulfed 228 companies at the end of November, with $180 billion of distressed debt, up from 225 companies in October with $166 billion of distressed debt, S&P Capital IQ reported.

Bonds are “distressed” when prices have dropped so low that yields are 1,000 basis points (10 percentage points) above Treasury yields. The “distress ratio” is the number of non-defaulted distressed junk-bond issues divided by the total number of junk-bond issues. Once bonds take the next step and default, they’re pulled out of the “distress ratio” and added to the “default rate.”

During the Financial Crisis, the distress ratio fluctuated between 14.6% and, as the report put it, a “staggering” 70%. So this can still get a lot worse.

The distress ratio of leveraged loans, defined as the percentage of performing loans trading below 80 cents on the dollar, has jumped to 6.6% in November, up from 5.7% in October, the highest since the panic of the euro debt crisis in November 2011.

The distress ratio, according to S&P Capital IQ, “indicates the level of risk the market has priced into the bonds. A rising distress ratio reflects an increased need for capital and is typically a precursor to more defaults when accompanied by a severe, sustained market disruption.”

And the default rate, which lags the distress ratio by about eight to nine months – it was 1.4% in July, 2014 – has been rising relentlessly. It hit 2.5% in September, 2.7% in October, and 2.8% on November 30.

This chart shows the deterioration in the S&P distress ratio for junk bonds (black line) and leveraged loans (brown line). Note the spike during the euro debt-crisis panic in late 2011:

The oil-and-gas sector accounted for 37% of the total distressed debt and sported the second-highest sector distress ratio of 50.4%. That is, half of the oil-and-gas junk debt trades at distressed levels! The biggest names are Chesapeake Energy with $7.4 billion in distressed debt and Linn Energy LLC with nearly $6 billion.

Both show how credit ratings are slow to catch up with reality. S&P still rates Chesapeake B- and Linn B+. Only 24% of distressed issuers are in the rating category of CCC to C. The rest are B- or higher, waiting in line for the downgrade as the noose tightens on them.

The metals, mining, and steel sector has the second largest number of distressed issues and sports the highest sector distress ratio (72.4%), with nearly three-quarters of the sector’s junk debt trading at distressed levels. Among the biggest names are Peabody Energy with $4.7 billion in distressed debt and US Steel with $2.2 billion.

These top two sectors account for 53% of the total distressed debt. And now there are “spillover effects” to the broader junk-rated spectrum, impacting more and more sectors. While some sectors have no distressed debt yet, others are not so lucky:

- Restaurants, 21 issuers, sector distress ratio of 21.4%;

- Media and entertainment companies, 36 issuers, distress ratio of 17%;

- High-tech companies, 22 issuers, distress ratio of 19%;

- Chemicals, packaging, and environmental services companies, 14 issuers, distress ratio of 16.1%;

- Consumer products companies, 16 issuers, distress ratio of 13.9%;

- Financial institutions, 14 issuers, distress ratio of 12.6%.

The biggest names: truck maker Navistar; off-road tire, wheel, and assembly maker Titan International; specialty chemical makers The Chemours Co. and Hexion along with Hexion US Finance Corp.; Avon Products; Verso Paper; Advanced Micro Devices; business communications equipment and services provider Avaya; BMC Software and its finance operation; LBO wunderkind iHeart Communications (Bain Capital) with a whopping $8.9 billion in distressed debt; Scientific Games; jewelry and accessory retailer Claire Stores; telecom services provider Windstream; or Texas mega-utility GenOn Energy (now part of NRG Energy).

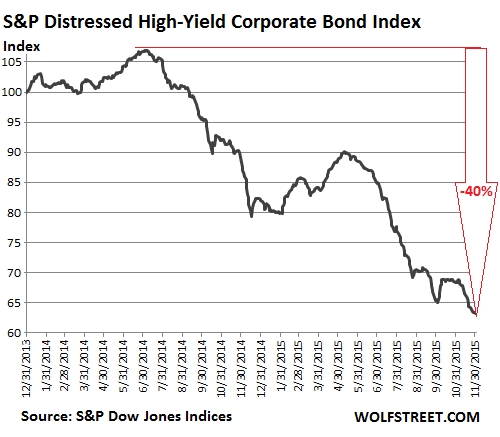

How much have investors in distressed bonds been bleeding? S&P’s Distressed High-Yield Corporate Bond Index has collapsed 40% from its peak in mid-2014:

In terms of investor bloodletting: 70% of all distressed bonds are either unsecured or subordinated, the report notes. In a default, bondholders’ claims to the company’s assets are behind the claims of more senior creditors, and thus any “recovery” during restructuring or bankruptcy is often minimal.

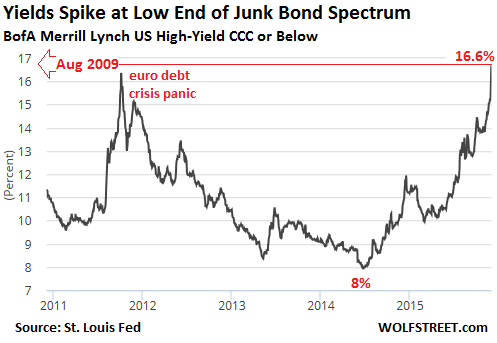

At the lowest end of the junk bond spectrum – rated CCC or lower – the bottom is now falling out. Yields are spiking, having more than doubled from 8% in June 2014 to 16.6% now, the highest since August 2009:

These companies, at these yields, have serious trouble raising new money to fund their cash-flow-negative operations and pay their existing creditors. Their chances of ending up in default are increasing as the yields move higher.

And more companies are getting downgraded into this club of debt sinners. In November, S&P Ratings Services upgraded only eight companies with total debt of $15.8 billion but downgraded 46 companies with total debt of $113.7 billion, for a terrible “downgrade ratio” of 5.8 to 1, compared to 1 to 1 in 2014.

This is what the end of the Great Credit Bubble looks like. It is unraveling at the bottom. The unraveling will spread from there, as it always does when the credit cycle ends. Investors who’d been desperately chasing yield, thinking the Fed had abolished all risks, dove into risky bonds with ludicrously low yields. Now they’re getting bloodied even though the fed funds rate is still at zero!

Other high-risk credits, such as those backed by subprime mortgages, will follow. And the irony? Just in the nick of time, subprime is back – but this time, it’s even bigger. Read… Subprime “Alt”-Mortgages from Nonbanks Run by former Countrywide Execs Backed by PE Firms Are Booming

Compound interest – eats the world.

Regards to the subprime mortgage info, thanks for linking.

It will be different this time! We have better lending guidelines! The investors ask hard questions!

A retired old-school banker I know used to have a book in his office with the seductive title “How to Borrow Your Way Out of Debt”. Upon opening, one found nothing but blank pages. But those were the days when bankers assessed credit risk on the borrower’s real PROFIT outlook and historical INCOME. If we were take such a view of most of these companies, I suspect that we would find blue sky, cooked books, and inflated real estate assets as the fictional collateral. Fraud on top of fraud………………….

So now we know why the executives of Countrywide Financial should have been put in jail the first time; then they couldn’t have plotted the next financial crisis. (See: http://tinyurl.com/hfqv354 )

It is interesting that “distressed” in this article pretty much refers to pricing alone and says little about whether it actually represents a significant change in the ability of companies to repay/refinance their debts. The charts show a similar spike that happened in 2012 without any real consequence to default rates. Of course we are right to not trust the rating agencies as they are lagging indicators and there is a prima facie case for oil being a potential disaster area, but the article give no evidence as to why the markets are right this time. They’ve been wrong before.

The definition of distress is also somewhat arbitrary – 1000bps stinks of being a round number rather than any meaningful economic measure. 900bps sounds pretty distressed to me. Or, as a bull might put it, a bargain!

Question: What mechanism brought distress down after the euro crisis in late 2011, and is it possible that mechanism, whatever it was, will work again?

It’s kinda like the post above on German domestic banks looking for profit from any rotten source. We are on the cusp of a new economy; keeping alive the old consumer/manufacturing economy is a dead end. Climate change came along just in time.

I’d like to thank the climate. It is an impeccable regulator.

Yep. Gaia’s gonna take care of the problem, and if it’s removing the irritant, so be it.

Lambert: Thanks for turning me on to the

Gaia hypothesis.

You’re welcome!

Yes, it’s likely there’ll be a lot of claret spilt on the carpet before she’s sorted us out.

Wait, wait a minnit– I thought, from the Absolutists posting here and elsewhere, that BONDS were a Sacred Holy Contract under which Investors were always entitled to Perfect Protection Against All Risks and Return of Capital Plus Stated Interest – a kind of no fault insurance, underwritten by Everyone Else!!! That’s not a correct statement of Bondholder Rights? The pillars of Heaven are shaken!

Oh, the Schadenfreude…