Yves here. The short answer is “a lot”. This analysis confirms Gabriel Zucman’s estimates on how much in assets is hidden (a mind-boggling 6+% of the total) but estimates the stealth income as much lower than his estimates. Mind you, the amounts not reported are so great that including the estimated losses would make the US look like a far less significant capital importer than it appears to be.

By Valeria Pellegrini, Senior Researcher, Banca d’Italia, Alessandra Sanelli, Head of the International and Withholding Tax Division, Banca d’Italia and Enrico Tosti, Senior Researcher, Banca d’Italia. Originally published at VoxEU

Balance of payments statistics suggest that assets held abroad are greatly underestimated – particularly for mutual fund shares and bank deposits. This column looks into the role played by tax havens and estimates that unreported financial assets amount to between $6 and $7 trillion. On this figure, the related tax evasion is between $19 and $38 billion a year on capital income, and between $2 and $2.6 trillion on personal income. Recent policy initiatives such as automatic information exchanges constitute real progress, but some critical aspects might jeopardise their effectiveness.

Over the last two decades, the growing volume of international financial transactions has allowed more and more taxpayers to escape domestic taxes by hiding their income and wealth abroad, particularly in offshore centres with strict banking and financial secrecy rules. Links and transactions with counterparts and subsidiaries located in tax havens provide individuals and business entities with channels to avoid or evade taxes or to transfer funds abroad.

The geographical breakdown of data reported in external statistics provides evidence of a prominent role of tax havens and offshore financial centres. Statistics on foreign direct investment show that, globally, almost one third of the foreign direct investment stock (inward and outward) refers to partners located in tax havens (UNCTAD 2015). As far as trade in services is concerned, the tax advantages offered by offshore countries have a significant impact on the geographical distribution, especially in the case of business services (Hebous and Johannesen 2015). The results of the most favourable voluntary disclosure schemes confirm that there are significant amounts of undeclared external assets held in tax havens. More generally, the analysis of global data from balance-of-payments statistics and international investment positions reveals that the portfolio liabilities reported globally by debtors are normally higher than the corresponding assets reported by investors of all countries (e.g. Lane and Milesi-Ferretti 2006). As these aggregates should coincide, it is reasonable to infer that the discrepancy stems from the underreporting of portfolio assets held abroad. Since corporations are subject to many regulatory checks (accounting standards, etc.), it is likely that most of the unreported assets belong to households. These hypotheses are the basis of our recent work (Pellegrini et al. 2015) on the hidden offshore wealth of households and tax evasion, which refines and updates our earlier studies (Pellegrini and Tosti 2011, 2012; Sanelli 2008).

In order to estimate a plausible magnitude of the undeclared assets held abroad, we compare the ‘mirror statistics’1 on portfolio assets and liabilities (shares, bonds, and mutual fund shares) on a global level, as taken from the Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey conducted by the IMF, and assume that measured discrepancies are a proxy of the undeclared external assets. The Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey does not include other financial assets, among which bank deposits. The amount of undeclared foreign bank deposits held by households may be estimated looking at Bank for International Settlements locational statistics on cross-border deposits of non-bank investors and taking a share2 of these deposits held both ‘in’ tax havens by residents of other countries and in non-haven countries ‘by’ tax haven residents.

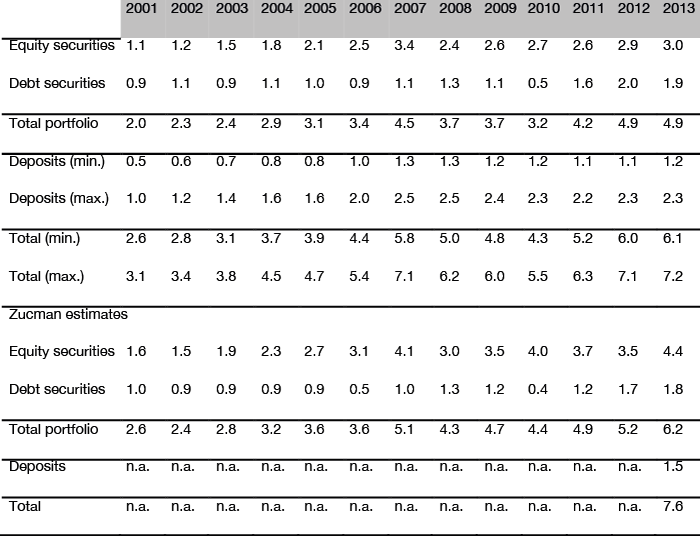

For the years 2001-2013, we estimate the global discrepancy between portfolio liabilities and assets (underreporting of assets) to be equal, on average, to 6.4% of world GDP. At end-2013 it amounts to $4.9 trillion. At the same date, undeclared foreign bank deposits may range between $1.2 and $2.3 trillion. The overall amount of unreported financial assets may then be estimated between $6.1 and $7.2 trillion. This amount represents a lower-bound estimate of the potential amount of undeclared wealth held offshore, as it does not include either other possible types of financial assets, such as life insurances or derivatives, or non-financial assets (such as real estate). Overall, the order of magnitude of unreported portfolio assets is not far from that estimated by Zucman (2013, 2015) with a similar methodology – $6.2 trillion for 2013, against our result of $4.9 trillion. The difference is mainly due to a higher amount of equity securities found by Zucman. As for bank deposits, his result is within the range of our estimate.

Table 1. Estimate of under-reporting of external financial assets (trillions of US dollars)

Sources: authors’ calculations (mainly on IMF and BIS data, see Pellegrini, Sanelli and Tosti, 2015) and Zucman (2015).

Tax Evasion Stemming from Unreported Assets

Starting from these results, we estimate the potential amount of international tax evasion linked to the unreported portfolio assets and bank deposits by assuming that most of the assets are held by individuals (either directly or through intermediate controlled entities) and that they give rise both to annual capital income tax evasion (on the basis of given rates of return) and to personal income tax evasion, this latter refers to the income from which the unreported assets originally arose.

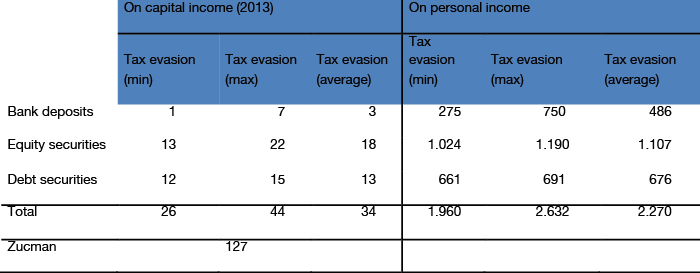

According to our estimate, at the global level international tax evasion on capital income might range between $19 and $38 billion a year. Personal income tax evasion estimated with reference to the stock of unreported capital at the end of 2013 ranges between $2 and $2.6 trillion, i.e. between 2.6% and 3.5% of world GDP.

To the best of our knowledge, similar estimates for personal income tax evasion are not available. As regards capital income tax evasion, for 2013 Zucman obtains a value of $127 billion, almost three times our maximum estimate of $44 billion. The difference is mainly due to the assumption of higher rates of return of the unreported assets – Zucman uses a single rate of return equal to 8%, whereas we prudentially use lower rates, differentiated by financial instruments, in the range of 0.5-3.3%. Namely, we calculate yearly interest rates on short-term (or sight) bank deposits by gathering IMF and ECB data (for European countries). For portfolio securities, we estimate actual average rates of return (respectively, in terms of dividends and interest) on the basis of the financial proceeds reported in balance of payments and the correspondent financial assets indicated in international investment positions.

Table 2. Estimate of tax evasion on undeclared external assets (billions of US dollars)

Automatic Information Exchange

The analysis of external statistics reveals that the amounts of undeclared assets held offshore and of the related international tax gap are significant.

Over the last few years, and namely after the Global Crisis of 2008-2009, unprecedented progress towards automatic information exchange between national tax authorities has been achieved thanks to the US FATCA legislation and the related Intergovernmental Agreements and through the Common Reporting Standard on Automatic Exchange of Information approved at OECD level in 2014. The crucial question is whether automatic information exchange represents an effective tool to fight international tax evasion.

Currently, a majority of countries in the world are committed to implementing automatic information exchange. As a matter of fact, full transparency and full access to information by tax authorities are far from being achieved. The main obstacles to an effective information exchange include, among others, persisting difficulties in the identification of ultimate beneficial owners, lack of reciprocity in many agreements on information exchange (namely, in a number of Intergovernmental Agreements negotiated by the US), problems of timeliness and margins of freedom left to national legislators in the implementation process, and loopholes in the information reporting provisions. In other words, the new measures will probably make tax evasion more difficult for small investors, but not for the bigger and more sophisticated ones who are often able to use complex structures to conceal their wealth abroad (see Zucman 2015, Economist 2015).

See original post for references

“the new measures will probably make tax evasion more difficult for small investors, but not for the bigger and more sophisticated ones”

One law for the plebes and another for the oligarchs. Yet again. Why is the US chasing the pennies when a few high-profile scores, aided by NSA data and a few competent auditors, could put the fear of G_d into the wealthy tax cheats?

Thos article doesn’t even touch on the purported “REMIC” trusts that aren’t. The amount of taxes owing is in the millions, or quite possibly billions.

.

There is a simple way to do this. We just need to convince Putin to put nuclear veapons in Grand Cayman, and the marines will close the place down in a New York minute.

Cut all the underground cable to the mainland and shoot all sat uplinks. The accounts are now “frozen”.

London, Switzerland, Monaco, Isle of Mann, etc… will have to be handled by the Chinese or that Dong dude ’cause that’s where Putin keeps all his money.

I wonder what economists make of the MMT idea that wealth accumulation is a black hole of money.

These are trillions of dollars parked to avoid taxes, doing nothing.

They would love to see that money put to good use in the public arena to help deal with inequality.

But they don’t want to wait for that to happen. They want to see some of the deficit money that is being spent now diverted to the common good in more of a ‘QE for the people’ type manner.

“They would love to see that money put to good use in the public arena to help deal with inequality.”

Wait, you mean the MMT crowd would like that to happen? Taxes don’t fund federal spending, any of this money that was taxed would literally be destroyed. The purpose of subjecting all this black hole money to taxation would be to simply get rid of it. Take away the ultra-riches cash, because they can’t be trusted with it.

True that. Taxes also give value to money so letting this slide tends to devalue the currency.

From Bill Mitchell, http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=32755

“”It follows that the imposition of the taxation liability creates a demand for the government currency in the non-government sector which allows the government to pursue its economic and social policy program.

This insight allows us to see another dimension of taxation which is lost in orthodox analysis.

Further, while real resources are transferred, the taxation provides no additional financial capacity to the government of issue.

Conceptualising the relationship between the government and non-government sectors in this way makes it clear that it is government spending that provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

That governments, as long as they can enforce the rule of law, have many options available to ensure they have sufficient taxing capacity to create the necessary real resource space to accommodate a public spending program.””

This goes to show that the use of “money” is totally flexible. Can’t collect those naughty taxes, well, we’ll still get along… the bigger problem the tax evaders have is their obsession with return on equity – leaving the haven is like leaving las vegas or the frantic illusion that everything is going to pay off bigtime – the real world is up and down, not just up. There are such sane tax rules as capital losses.

“The main obstacles to an effective information exchange include, among others, persisting difficulties in the identification of ultimate beneficial owners, lack of reciprocity in many agreements on information exchange (namely, in a number of Intergovernmental Agreements negotiated by the US), problems of timeliness and margins of freedom left to national legislators in the implementation process”

Little nuggets like this tell me all I need to know about these mass surveillance treaties. Of course margins of freedom left to national legislators are a problem, make them too wide and these savages may actually get it in their little heads, God forbid, that they should be making laws in their countries, when obviously the select few in Washington and Brussels are the only ones qualified for this job. They should go back to picking cotton, herding pigs or whatever is the reason these uppity peasants are even allowed to exist.

I find the thesis somewhat contradictory – aren’t corporations primarily the ones with access to sophisticated techniques and complex structures used to evade taxation?

This:

Since corporations are subject to many regulatory checks (accounting standards, etc.), it is likely that most of the unreported assets belong to households.

seems to contradict this:

In other words, the new measures will probably make tax evasion more difficult for small investors, but not for the bigger and more sophisticated ones who are often able to use complex structures to conceal their wealth abroad…

And the “likely” bit is not substantiated.

Is the piece misdirection or just misguided? It would be helpful to get a survey of the totals of tax evasion and a breakdown thereof by category – individuals, corporations, and other entities.

I think it’s the matter of difference between tax avoidance (legal) and tax evasion (illegal). What corporations do is generally the former – exploiting regulatory loopholes and inconsistencies to shift their profits into lowest taxed areas possible. In the end, a publicly traded corporation cannot just hide the money, because that would amount to meek performance (lower dividends for stockholders) at best and embezzlement at worst.

This article concerns tax evasion – illegal nonpayment of taxes, primarily achieved by hiding money and other assets from the government. Thus the small investors vs. bigger and more sophisticated ones distinction is probably about different individuals – i.e. Jill Average could no longer afford to hide her 100000$ savings from IRS, but Koch brothers will still find a way.

In other words, corporate CEO can invent a new strategy like “Dutch Sandwich” to minimise corporate tax, but it has to be legal and everything is on the books. A CEO cannot simply withdraw cash from corporate account, pack it into a suitcase, smuggle it, put it in a Swiss bank account and don’t tell anybody, because this isn’t his money, it belongs to shareholders. This is however what individuals can do with their personal income.

Interesting spike in under-reporting of external financial assets ahead of the financial crisis (2007) with figures increasing into 2013, as well.

From the 2015 OECD/BEPS executive summary report (page 33):

“Although measuring the scale of BEPS proves challenging given the complexity of BEPS and the serious data limitations, today we know that the fiscal effects of BEPS are significant. The findings of the work performed since 2013 highlight the magnitude of the issue, with global corporate income tax (CIT) revenue losses estimated between 4% and 10% of global CIT revenues, i.e. USD 100 to 240 billion annually. Given developing countries’ greater reliance on CIT revenues, estimates on the impact on developing countries, as a percentage of GDP, are higher than for developed countries.

In addition to significant tax revenue losses, BEPS causes other adverse economic effects, including tilting the playing field in favour of tax-aggressive MNEs, exascerbating the corporate debt bias, misdirecting foreign direct investment, and reducing the financing of needed public infrastructure.”

http://www.oecd.org/ctp/beps-reports-2015-executive-summaries.pdf