We’ve written from time to time that not all debt is created equal. Prudent business borrowing enables companies to make investments and expand operations. And even though governments like the US that issue their own currency may nevertheless sell bonds, operationally they can simply create more dough to fund spending. The constraint on spending is creating too much inflation, not bankruptcy. And since as we’ve regularly discussed, the business sector chronically underinvests, deficit spending is necessary and desirable most of the time. Economist Mariana Mazzucato has argued that there are certain risks, such as engaging in basic research, where the uncertainty is too great for entrepreneurs. And that’s before getting to the fact that the party that makes the discovery could easily see its technology exploited by free riders.

However, economic studies have regularly found that high levels of household debt is a negative for economic growth. Moreover, some economists have found a strong relationship between high levels of consumer debt and economic crises. Yet if you read the business press, analysts and government officials see rising consumer borrowing as a plus for growth. How does that make sense?

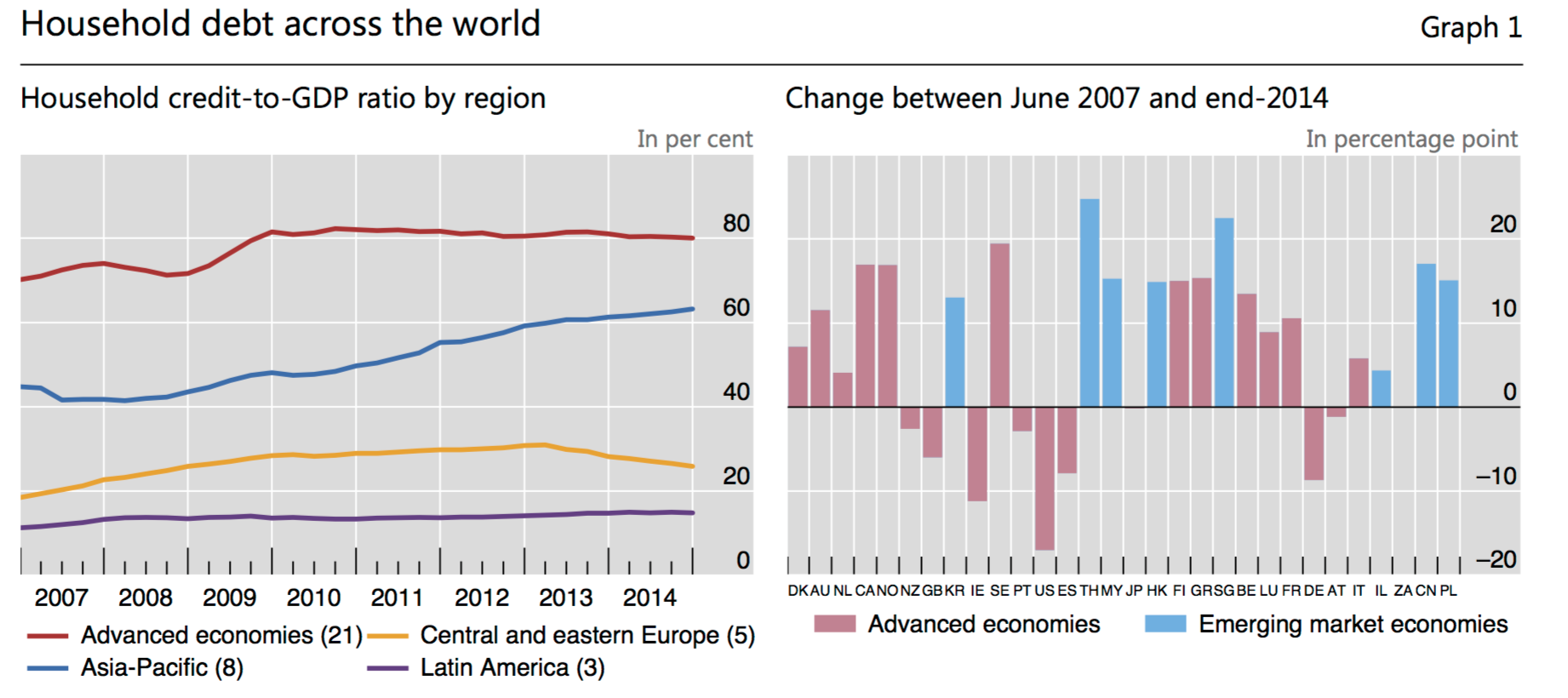

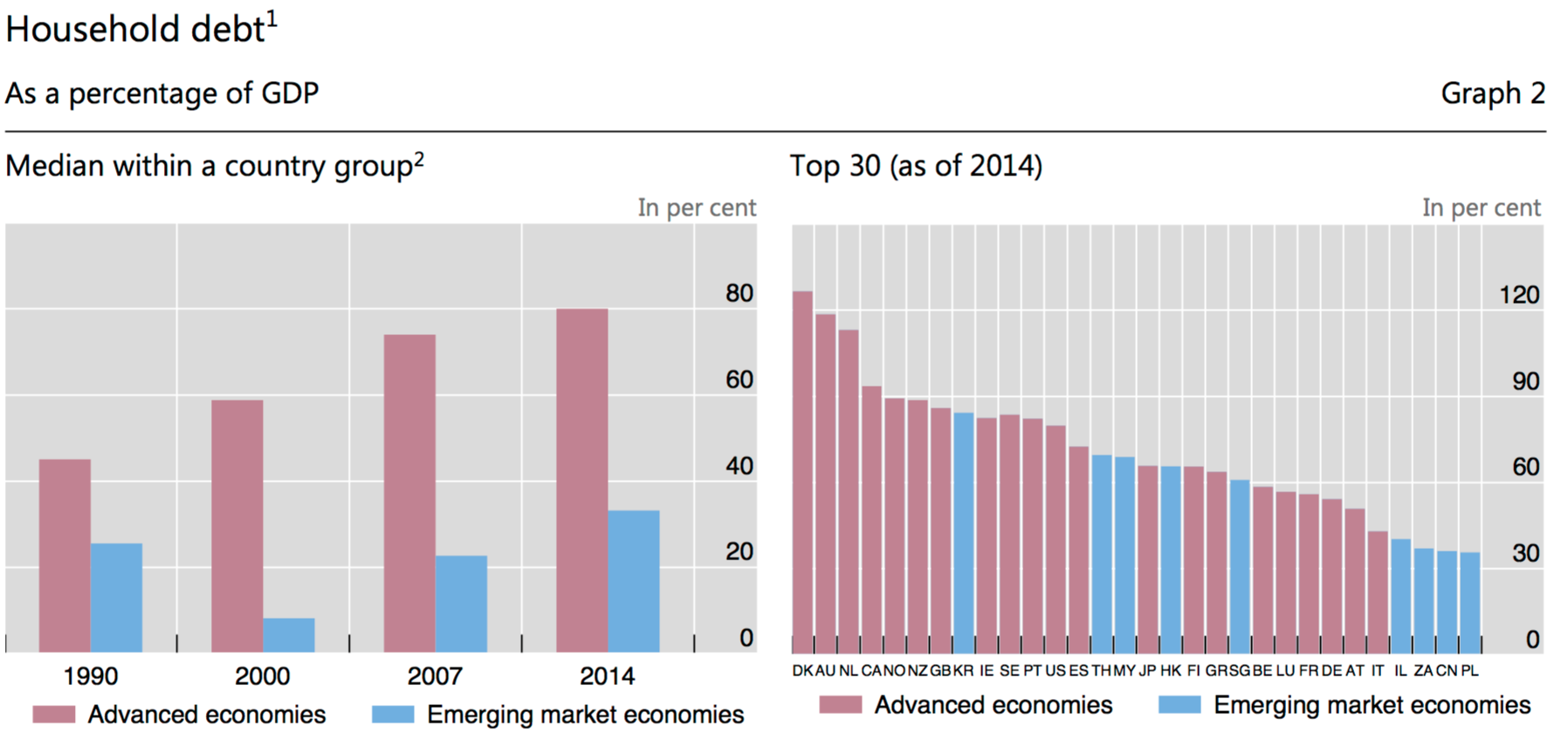

A recent Bank of International Settlements paper (hat tip UserFriendly) helps reconcile this apparent paradox. The immediate impact of household borrowing does indeed spur the economy near-term but creates drag down the road. And the level at which household borrowing becomes a net negative is 60% of GDP, when nearly all advanced economies are at higher levels. Worse, the dampening effect is more pronounced when the household debt to GDP level exceeds 80% The BIS puts the US as above that threshold

From the study by Marco Lombardi, Madhusudan Mohanty and Ilhyock Shim:

Our results suggest that debt boosts consumption and GDP growth in the short run, with the bulk of the impact of increased indebtedness passing through the real economy in the space of one year. However, the long-run negative effects of debt eventually outweigh their short-term positive effects, with household debt accumulation ultimately proving to be a drag on growth. Our estimates suggest that a 1 percentage point increase in the household debt-to-GDP ratio tends to lower output growth in the long run by 0.1 percentage point, suggesting that policy makers face non-trivial, real costs in stimulating the economy through credit expansion. These findings are robust to alternative lag structures and control variables. Our analysis of the threshold effect suggests that the negative long-run impact of household debt on consumption growth intensifies as the household debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds a threshold of 60%. The estimated threshold is somewhat larger for GDP growth, with the negative debt effects intensifying as the household debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 80%.

And what did they find explained most of the differences among the 54 countries they studied from 1990 to 2015? How much power the lenders had in forcing borrowers to pay them back:

Another interesting aspect of our results is the role of country-specific characteristics in determining debt limits. One key result is that the only institutional factor able to account for cross-country variation is the degree of legal protection of creditors. In particular, we find that countries with stronger creditor protection tend to experience more drag on long-run growth from higher levels of household indebtedness. We interpret this result as implying that in countries with stronger creditor rights, household borrowers are less likely to default on their loans and more likely to service their debt in the long run. This reduces consumption growth and eventually GDP growth to the extent that banks in the countries do not sufficiently reduce ex ante their loan spreads in consideration of higher expected earnings due to stronger creditor rights.

Note that this paper isn’t set up to capture what amounts to changes in the legal regime. In particular, in the US, mortgage borrowers had the belief, which historically was sound, that if they got into trouble, as in had a work interruption or a financial emergency, that the bank would work with them, as they do with business borrowers who have a bad spell but look to be viable in the long run. That went out the window with the rise of mortgage servicing, since the servicers found it more profitable to foreclose than modify loans, even though the investors would also do better with a successful mortgage modification than a foreclosure sale.

And you can see that in this chart. The US has supposedly had the largest post-crisis household deleveraging of any advanced economy, and much of that was involuntary, meaning the result of foreclosures. Banks also became stringent post crisis about issuing new mortgages, more the result of typical behavior and the need to strengthen their balance sheets than the favorite scapegoat of regulations:

And even with all of its deleveraging, the US is still just above the 80% level1:

The researchers tried to decompose long versus short-term effects:

The right-hand panel of Graph 3 makes two points very clear. First, past increases in household debt are not a good predictor of positive growth but appear to be associated with weaker consumption and higher risks of recession. Second, the downward-sloping line suggests that the negative correlation between household debt and consumption actually strengthens over time, following a surge in household borrowing. What is striking is that the negative correlation coefficient nearly doubles between the first and the fifth year following the increase in household debt.

As is well known, simple correlation does not suggest anything about the causal effects. That said, the preliminary evidence in Graph 3 appears to support the view that credit expansions may have very different effects on the short- and medium-run economic prospects of countries. It also confirms the findings of King (1994) that large increases in private debt in the 1980s made many OECD countries vulnerable to problems of weak growth and “debt deflation”. He shows that the most severe recessions since the 1930s have occurred in countries that have seen the largest increases in private debt in the preceding five years.

If you like nerdy papers, you’ll enjoy the data analysis here. In addition to using several different methodologies to examine the data, they also tested extensively for cross-country explanatory variables and robustness.

The authors point to the open policy questions at the end:

An important question, on which this paper is largely silent, is the role of various factors in the accumulation of household debt.20 One key issue in the context of the risk-taking channel of monetary policy (Borio and Zhu (2012)) is the extent to which low short- and long-term rates over the past eight years may have played a role in the recent rapid rise in household debt in many countries and may even have constrained central banks in raising rates. Even though such a question remains beyond the purview of this paper, any assessment must consider the various short- and long-run effects associated with any strategy aimed at stimulating the economy through ever larger debt levels.

Let us offer our own bit of speculation from ECONNED in 2010:

Let’s use a different metaphor to illustrate the problem. Say a biotech firm creates a wonder crop, the most amazing creation in the history of agriculture. It yields far more calories per acre than anything else, is nutritionally extremely complete, and can be planted and harvested with far less machinery and equipment than any other plant. It is tasty and can be prepared in a wide variety of ways. It is sweet too, so it can be used in place of sugar and high fructose corn syrup at lower cost. We’ll call this XCrop.

XCrop is added as a new element in the food pyramid and endorsed by nutritionists and public health officials all over the globe. It turns out that XCrop also is an aphrodisiac and a stimulant (hmm, wonder how they engineered that in) and between enhanced libido and more abundant food supplies, the world population rises at a faster rate.

Sales of XCrop boom, displacing traditional agriculture. A large amount of farmland is turned over from growing other types of produce to XCrop. XCrop is so efficient that agricultural land is taken out of production and turned to other uses, such as housing, malls, and parks. While some old-fashioned farms

still exist, they are on a much smaller scale and a lot of the providers of equipment to traditional farms have gone out of business.Twenty years into the widespread use of XCrop, doctors discover that diabetes and some peculiar new hormonal ailments are growing at an explosive rate. It turns out they are highly correlated with the level of XCrop consumption in an individual’s diet. Long-term consumption of high levels of XCrop interferes with the pituitary gland, which controls almost all the other endocrine glands in the body and the pancreas.

The public faces a health crisis and no way back. It would be very difficult and costly to put the repurposed farmland back into production. Some of the types of equipment needed for old-fashioned farming are no longer made. And with the population so much larger than before, you’d need even more farm- land than before. The world population has become dependent on the calories produced by XCrop, so going off it quickly means starvation for some. But staying on it is toxic too. And expecting users simply to restrain themselves will likely prove difficult. The aphrodisiac and stimulant effects of XCrop make it addictive.

Advanced economies have become hooked on debt technology, which, like XCrop, is habit forming and hard to wean oneself off of due to its lower cost and the fact that other approaches have fallen into partial disuse (for instance, use of FICO-based credit scoring has displaced evaluations that include an assessment of the borrower’s character and knowledge of the community, such as stability of his employer). In fact, the current debt technology results in information loss, via disincentives to do a thorough job of borrower due diligence (why bother if you are reselling the paper?) and monitoring of the credit over the life of the loan. And the proposed fixes are not workable. The Obama proposal, that the originator retain 5% of the deal and take correspondingly lower fees, is not high enough to change behavior. And a level that would be high enough to make the originator feel the impact of a bad decision would undercut the cost efficiencies that made securitization popular in the first place. You’d have better decisions, but less lending, and higher interest rates. That’s ultimately a desirable outcome, but as in the XCrop situation, no one seems prepared to accept that a move to healthier practices will result in much more costly and less readily available debt.The authorities want to believe they can somehow have their cake and eat it too.

Note this hasn’t proven to be quite correct; the most rapidly growing category of consumer debt post crisis has been student debt. With most loans government guaranteed, investors have no credit concerns…but the high level of delinquencies and defaults attests to the severity of that ticking time bomb. And we have the more immediate effect that generous student loans simply produce more college education cost bloat, while leaving many graduates with debt burdens that in many cases keep them from getting married, buying a house, and starting a family, and can wind up being a millstone.

Yet both parties shy away from addressing this issue. The Democrats are particularly complicit since academia serves as an informal but very large addition to their think-tank apparatus. Where is our William Jennings Bryant, who will talk about a cross of debt?

__________

1 Bear in mind that the researchers made adjustments for consistency, which may explain why their figures for the US, which exclude student debt (they consider only borrowings made via banks, while the Federal government makes the majority of student loans via colleges) come up with a higher debt to GDP ratio than if you take the New York Fed’s quarterly report on household debt for year end 2016, and divide that by the fourth quarter GDP just released.

And NOT a word of our massive DEBT, in last night’s prez speech! There was NONE during the election debates and none during the ‘state of our union’ address!

Yeah, stumbled across it because I was curious which countries had the highest levels of private debt to GDP (includes business too) and the BIS is the sources of that data for FRED. Oddly enough it is the Nordic countries if anyone cares. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=cSuY

But much of that is lent by the state.

Not only do they shy away from it, they actively push BS research saying it isn’t a problem, shut up you stupid grads, you’ll earn more over your lifetime. Student debt is actually good for you.

I would punch Obama in the face if I ever got the chance.

Given his and Michelle’s outrageous mega book advances this morning I think you’d better take a number and form an orderly queue (or is it line?) with the rest of us.

May I be so bold as suggest, ‘To Fool A Nation: Confessions Of A Wall St Stooge’ ?

‘Rope-A-Dope with Hope’?

“They don’t let President’s Wear Comfortable Shoes; So I decided to Pay Bankers to Foreclose on Your House Insead!” You’re Welcome!!!

Ah, yes. The good old “student debt is actually good for you” line. Alas, it’s increasingly BS. Every year, tuition rises faster than the wages used to repay that student debt. Every year, the deal get crummier and crummier.

I think the reason our government defends it, though, is because they think they make a profit. [Elizabeth Warren once said the Feds reaped $50 billion in annual profits as part of an argument for lower interest rates on student debt.] Alas, even that part isn’t true:

http://money.cnn.com/2016/08/04/pf/college/federal-student-loan-profit/

And that article was written before it was discovered that the government was miscalculating student loan default rates:

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/01/16/feds-data-error-inflated-loan-repayment-rates-college-scorecard

Yes. Obama would deserve that punch. Under his oversight, the US Department of Education transformed itself into the greatest predatory lender of all time. And they’re losing money anyway. Only our bloated colleges reap any benefit.

Correction (minor): Only the bloated administrative staff and consultants associated with the University Industrial Complex reap any major benefit!

Student loan debt is the new birth control. 2016 U.S. fertility rates have fallen to lowest on record. 59.6 births per 1,000 women . According to Pew Research we are heading toward negative zero population growth, that is to say, like Europe we are closing in on falling short of the approximate generation replacement.

This is why.

http://www.cheatsheet.com/politics/this-is-what-the-recession-did-to-millennials.html/?a=viewall

At American consumption levels, negative population growth is a good thing?

I do love student debt. The lenders earn interest in exchange for taking on basically no risk due to the government backing. The whole setup is almost achingly beautiful in it’s own evil and corrupt way.

Of course a crazy person might ask why the government doesn’t simply make the loans directly. Or for that matter just fund education the way those strange beings in the topsy-turvy antimatter universe called “most of the rest of the developed world” do. After all, even my mainstream macro textbooks claimed that such spending resulted in a great enough increase in income and productivity down the line that it actually costs less than zero…

Um. The government does make student loans directly. The US Department of Education issues over 90% of student loans. [The remaining fraction is done by the private sector, primary for medical and law school. Those loans are no longer federally-backed, but still cannot be discharged in bankruptcy.] This was a change made by the Obama administration as part of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010.

Unfortunately, this has not been better for the students. The total amount of monies lent have skyrocketed, and the Department of Education uses recollection tactics that have been (quite rightly) outlawed in the private sector. They’ve crushed an entire generation of students with excess debt, and they’re ruthless with their efforts to claw the money back.

In my opinion, this is part of why Trump won the election. Federal policy is clearly broken here, and Democrats didn’t even seem aware of the problem until the election season. Too busy proclaiming that “America is already great”.

I think this may be a bit of sleight of hand.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Student_loans_in_the_United_States

“”Federal Direct Student Loans, also known as Direct Loans or FDLP loans, are funded from public capital originating with the United States Treasury. FDLP loans are distributed through a channel that begins with the U.S. Treasury Department and from there passes through the United States Department of Education, then to the college or university and then to the student.

In 2013, the federal debt had grown to $16.7 trillion. Six percent of that debt comes directly from student loans making student loans only second to mortgages in consumer debt.””

—————–

The federal government could fund these students directly but instead they are going into debt by taking out loans from private banks. The Treasury is letting private banks take on the role of money creation for these loans and then enforcing that they get paid back.

Aye, they could… But would that make any difference to the students? After all, these are still student LOANS. Students are still expected to pay the money back. It’s still real debt and it’s still a real burden that is causing real problems.

In that sense, it doesn’t matter if the money creation happens at the Federal Reserve and goes through the mega-banks on the way to the US Treasury, or if that money is directly declared into existence by the Treasury as part of some giant MMT scheme. Either way, the students still get screwed while the universities wallow in dough.

What I’m saying is that they wouldn’t have to be loans. The federal government can hand out the money without having to be paid back. This also may make them more interested in how that money is spent. Such as on better professor pay rather than administration.

Well, hey, if they’re going to hand out money without having to be paid back, why limit it to education? The little econobox I drive these days is getting rather long in tooth. Why not have the government buy me a brand-new Cadillac?

Or maybe they could buy me a little vacation condo in Florida, so that I could enjoy sunnier winter holidays there?

Both of these would be cheaper than the educations some students have managed to purchase these days, and both would support manufacturing jobs directly. We wouldn’t have to wait for the the hypothetical gains of a college education to finally appear, especially since those gains get more tenuous every year.

If the government is simply going to start buying really expensive stuff for people, I want something too!!

Definitely. The point is more to get public control over the public money supply so it can provide what the public wants.

This would seem to include single payer health care and cheaper education without the massive student debt problem. A job guarantee program would also be useful. These sorts of things can put money into the economy in a productive way.

When you say “public control”, do you mean control by the federal government, control by state/local governments, or control by individual citizens? Because I gotta tell you, control by federal government has worked out poorly for lots of people.

Remember that Obama spent billions on bailouts and billions more on stimulus. Some people got tons of money that way. Most others, though, saw little or none. [Beyond the payroll tax holiday, I personally got zilch.] This is part of why the Democrats lost the election. The benefits they brought were much too haphazard and left too many people out.

And now that Trump has taken the reins, a different small group of people will reap the benefits. Namely, the defense contractors, and likely the wealthy. Most of the public will once be left out again.

This is the problem with relying on government to “put money into the economy in a productive way”. Different people in government have different ideas of what constitutes productive. Policies can change radically after an election.

And even worse, we rarely see the benefits promised. And somehow whole categories of people always get excluded. All of this causes overall resentment in society to grow even more.

If you want to print money and put it into the economy to help people, give it to people directly. That way everybody can use the money to address their own actual needs. Not what the latest idiot in DC thinks their needs are. After the failures of Obama and the almost certain failures of Trump to come, why would we want to put our hopes in “productively-spent” government money?

I think the first step would be to try and get a general public understanding that there is no need for the banks to be creating our public money supply and then they get the ‘first use’ benefits in terms of interest.

The federal government has control of who can create money.

I also think the best way to look at what needs funding is to look at the state and local government level and have the federal government support these programs. Takes a lot more democratic participation than we have now.

The federal government can directly do large programs like single payer or extended social security.

And what would you getting a free Cadillac do for me, Grumpy Engineer? There is a big difference here that so many of you refuse to recognize.

When we educate our children, we do a great deal to ensure that our future years will be more pleasant. The more those children earn in their lifetimes, the more taxes they pay, the more “nice things” we get, like medical benefits and Social Security, a more stable economy, better paying jobs, more solutions to our problems, and I could go on infinitum……and the less we burden them with debt, the faster they can get to work…..

Free education for our children seems to me to be a way to get an great return on our tax dollar investment, as opposed to your Cadillac which will just depreciate over the years…….

My free Cadillac wouldn’t do a damned thing for you. Your own free Cadillac would be the answer to that. And when they depreciate enough, they could buy us replacements. Right? [For the record, I’m NOT advocating this. I’m poking holes at financial matter’s argument for money printing.]

But more seriously… If the education for our children were such a great investment (more earnings, more taxes, etc.), then we wouldn’t see so many students struggling with their student loans. It’s gotten too damned expensive. For far too many students, it wasn’t the good investment you claim it is, but instead became a source of financial ruin. Increasingly, only highly-paid professionals (lawyers, doctors, computer scientists, engineers, etc.) reliably come out ahead.

And if we cough up gobs of federal dollars to rescue people with less valuable educations from this ruin, a question of fairness comes into play. What about those people who don’t go to college at all? [After all, college is neither appropriate nor necessary for everybody.] What benefit do they get? The same sort of trickle-down benefits from their better educated peers that you describe? No wonder they voted for Trump.

I’d rather we returned to the days before the government started subsidizing student loans, back when colleges cared about cost-effectiveness and kept their tuitions quite low. It wasn’t free, but it was certainly affordable. [My dad paid for every year of school with a summer’s worth of minimum wage earnings. That strategy isn’t remotely viable now.]

On the other hand, having the government pay for Cadillacs would support those workers’ wages and GM’s ability to pay for their medical care and pensions. With more automobiles being purchased, there would be more need for automotive workers, which means more paychecks and more payroll taxes being paid. And if the government bought us a new Caddy every 3 years regardless of the state of the economy, the job situation at GM would be super-stable.

This list of benefits sounds much like the one you listed, except that we would more confident that the benefits would actually happen.

Of course, if the government started buying everybody Cadillacs and you worked at Ford or Chrysler… Well, that would suck. This is why I’m skeptical of the government printing money to buy freebies for anything. It’s terrific if the government is buying YOUR stuff. For everybody else, though… You gotta wait for the benefits to “trickle down”.

The Treasury is letting private banks take on the role of money creation for these loans and then enforcing that they get paid back.

Does that mean the wiki article needs to be modified as follows?

P.S. if the Treasury itself was providing the financing (i.e. through tax payments and bond sales), then that would not be increasing the monetary base. But if it’s the private banks that are providing the financing, then this should be increasing the monetary base. Yay inflation!

No need to use tax payments or bond sales. This would increase the monetary base but that can be good when there is unemployment and unused capacity.

The problem with the private banks issuing the money is that it has to be paid back with interest which drains money from the system.

Interest payments do not leave the private sector. Students or parents pay interest to private sector banks, CEO’s, and shareholders. Simply flows upwards from lower income to upper income cohorts. Subsequently a little drips back down to gardeners etc, all according to plan.

Getting the government to be the one making the profits off federal student loans instead of private companies was one of the first things Elizabeth Warren did in the senate, She wanted to bring down interest rates too so that they broke even but the GOP never passes up a chance to screw over poor people.

And they can’t make college free because then they wouldn’t have been able to roll over the mortgage bubble into the student debt bubble.

http://www.stlouisfed.org/~/media/Files/PDFs/HFS/assets/2016/Alpert_Hockett_postcrisis_progress_report.pdf

Elizabeth Warren wanted to bring down interest rates because she foolishly believed the bogus profit numbers that the Department of Education provided (almost certainly computed using accounting methods that are illegal in the private sector). Warren said $50 billion in annual profits. A more accurate accounting put it at a mere $1.6 billion. And a truly honest accounting puts the losses at nearly $21 billion.

http://money.cnn.com/2016/08/04/pf/college/federal-student-loan-profit/

And that article was written before it was discovered that the government was underestimating student loan non-payment rates:

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/01/16/feds-data-error-inflated-loan-repayment-rates-college-scorecard

Crap like this is why the idea of disbanding the Department of Education entirely is starting to gain traction. Their behavior arguably classifies them as a predatory lender. They’re hurting people.

And yet, the ones really making the big bucks off federal student loans are the “educators” who charge ridiculously inflated tuition and fees. And they tell their marks, I mean students, not to worry, because they’ll have no trouble paying it all off with the fabulous wages they’ll be making.

Neo-liberalism’s flawed neoclassical economics has turned the global economy into an empire of debt.

Before 2008 it was just the West that loaded up on debt, after 2008 the emerging markets have done the same thing.

Debt allows you to borrow money from the future and one day that impoverished future will arrive.

Central Bankers are already putting in trillions trying to stave off the debt deflation that is trying to take hold.

Their efforts can only maintain stagnation at present and there are still many asset bubbles that have yet to burst.

The sudden bursting of asset bubbles causes money destruction on bank balance sheets and a contraction of the money supply. Then debt deflation will take the upper hand.

Neoclassical economics destroyed itself in the debt deflation of the 1930s.

It’s going to do the same again.

Einstein’s definition of madness “Doing the same thing again and again and expecting to get a different result”

Debt based consumption and speculation, what could possibly go wrong?

The same things that went wrong last time.

If you want things biased in your favour, bias the economics that everything runs on.

The Classical Economists looked out on a world of small state, basic capitalism in the 18th and 19th Centuries and observed it. It is nothing like our expectations today because they are just made up.

Adam Smith in the 18th century:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money.”

We still have a UK aristocracy that is maintained in luxury and leisure and can see associates of the Royal Family that are maintained in luxury and leisure by trust funds. As these people are doing nothing productive, nothing can be trickling down, the system is trickling up to maintain them.

Adam Smith in the 18th century:

“But the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity and fall with the declension of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin.”

Exactly the opposite of today’s thinking, what does he mean?

When rates of profit are high, capitalism is cannibalising itself by:

1) Not engaging in long term investment for the future

2) Paying insufficient wages to maintain demand for its products and services

Today’s problems with growth and demand.

The Classical Economists direct observations come to some very unpleasant conclusions for the ruling class; they are parasites on the economic system using their land and capital to collect rent and interest to maintain themselves in luxury and ease (Adam Smith above).

What can these vested interests do to maintain their life of privilege that stretches back millennia?

Promote a bottom-up economics that has carefully crafted assumptions that hide their parasitic nature.

It’s called neoclassical economics and it’s what we use today.

The distinction between “earned” and “unearned” income disappears and the once separate areas of “capital” and “land” are conflated. The landowners, landlords and usurers are now just productive members of society and not parasites riding on the back of other people’s hard work.

Unearned income is so easy, it’s the UK favourite today.

Most of the UK now dreams of giving up work and living off the “unearned” income from a BTL portfolio, extracting the “earned” income of generation rent.

The UK dream is to be like the idle rich, rentier, living off “unearned” income and doing nothing productive.

Powerful vested interests come up with neoclassical economics so that it works in their favour and only bottom-up economics can be easily corrupted. Top-down economics is based on real world observation.

Their neoclassical economics blows up in 1929 due to its own internal flaws but the powerful vested

interests still love it as they designed it.

Keynes comes up with new ideas that herald the New Deal and a way out of the Great Depression.

The powerful vested interests don’t want to lose their beloved neoclassical economics and fuse it with Keynes ideas to roll out after the war. This gives them the opportunity to get rid of some of Keynes’s more unpleasant conclusions, generally tone it down and remove all the really obvious conflicts with their neoclassical economics. The only real Keynesian economics was in the New Deal.

When the Keynesian synthesis fails in the 1970s, they seize the opportunity to bring back their really biased neoclassical economics.

It still doesn’t work of course.

“All for ourselves, and nothing for other people seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

Mankind first started to produce a surplus with early agriculture.

It wasn’t long before the elites learnt how to read the skies, the sun and the stars, to predict the coming seasons to the amazed masses and collect tribute.

They soon made the most of the opportunity and removed themselves from any hard work to concentrate on “spiritual matters”, i.e. any hocus-pocus they could come up with to elevate them from the masses, e.g. rituals, fertility rights, offering to the gods …. etc and to turn the initially small tributes, into extracting all the surplus created by the hard work of the rest.

The elites became the representatives of the gods and they were responsible for the bounty of the earth and the harvests. As long as all the surplus was handed over, all would be well.

Later they came up with money.

We pay you to do the work and you give it back to us when you buy things, you live a bare subsistence existence and we take the rest (profit). The money scam is the basis of capitalism.

Nothing really changes.

Slaves lived a bare subsistence existence in the same way that UK workers, men, women and children, in UK factories, lived a bare subsistence existence.

US slave owners made the claim that they treated their workers better because they owned them rather than rented them, a point with some validity at the time.

The masters of mankind abuse all to enrich themselves; there is always fabulous wealth at the top as those at the bottom live a bare subsistence existence, e.g the pharaohs, Versailles, UK early 19th Century …….. etc ….. today.

Then the Classical Economists turn up and work out the ruling class are parasites.

This economics is going to be a problem!

The sudden bursting of asset bubbles causes money destruction on bank balance sheets and a contraction of the money supply. Then debt deflation will take the upper hand.

Preventing contraction. That’s the name of the game. I don’t think the Fed Reserve gives a rats ass about what this paper being highlighted by NC is saying. All the Fed Reserve cares about is making sure their little game doesn’t go into reverse (contraction). Everything else is “virtuous”, lol. Even low GDP.

By the way, I think technically debt that is written off (defaulted) doesn’t really shrink the money supply. Rather, it’s when debt is retired (paid off), that’s when the money supply shrinks. In contrast, if debt is defaulted, that’s currency in the money supply that others can use to pay off their debts.

So the game for the Fed Reserve is to make sure that new debt retirement is eclipsed by new debt creation.

One way is to let the “risk takers” know that their back is covered. Watch in wonder as the stock market and other assets climb the wall-of-worry, lol. The only difference between us and the Weimar republic is the latter didn’t have a wall-of-worry.

Another is letting the wanna-bes take the real risk, student debt. Assuming student debt is financed by private banks and not the Fed Gov (the latter of which simply recycles the existing monetary base out of the hoards of the wealthy back into the economy.)

Bankers are given the privilege of creating money out of nothing for loans which they can charge interest on.

In reality it provides a mechanism for you to borrow your own money from the future and the interest you pay is the charge for this service. You pay the initial sum, plus the interest, back in the future and get to spend that money today on a house or a car or whatever.

When the debt has been paid off everything is back to square one but the bank has charged interest for the service it has provided.

When there is a default, the bank needs to repossess the asset and recoup the outstanding debt to square that debt.

When bubbles burst the asset backing the loan can fall in value so that it does not cover the outstanding debt leading to a loss for the bank.

When the debt has been used to buy securities that suddenly acquire a zero value (sub-prime mortgage backed securities in 2008) money gets destroyed very quickly.

Fundamentals always win out in the end although the markets can be distorted for a long time.

The FEDs game will be over when the real economy deteriorates to such an extent that reality re-asserts itself.

Even a single large shock could jolt everyone back to reality.

“Einstein’s definition of madness “Doing the same thing again and again and expecting to get a different result”

You should look up the context to that quote, about as abused as the Uncertainty Principle – author has taken umbrage at it…

Keynesian economics was political replaced by vested interests with an ideological agenda after being able to subvert democracy via institutionalization of key information and public institutions. This series of ratchet like events dovetails with increased excessive profit taking, wage suppression, privatization, financialization, atomistic sociaty et al…

disheveled…. don’t have the time so…. http://www.softpanorama.org/Skeptics/Political_skeptic/Neoliberalism/index.shtml

A fundamental flaw in today’s neoclassical economics means global policy makers keep making the wrong decisions.

2008, the real estate booms and busts around the world, Greece and the decline of the Club-Med nations are all consequences of the flaw in today’s economics.

Neoclassical economics uses fundamentally flawed assumptions on money and debt.

The IMF predicted Greek GDP would have recovered by 2015.

By 2015 it was down 27% and still falling.

This is the flawed assumptions on money and debt at work.

Money = Debt

Money is created by loans and destroyed by the repayment of those loans.

A nation’s money supply is controlled by the debt in the system.

The money supply goes up when more new debt is being taken out than repayments being made. The money being created exceeds that being destroyed.

The money supply goes down when more repayments are being made than new debt is being taken. The money being destroyed exceeds that being created.

It is the money creation in real estate booms that make them feel so good and the money destruction in real estate busts that makes them feel so bad. The money creation and destruction feeds out into the rest of the economy intensifying the effects of the boom and bust.

This is the money creation going on before 2008:

http://www.whichwayhome.com/skin/frontend/default/wwgcomcatalogarticles/images/articles/whichwayhomes/US-money-supply.jpg

Everything is reflected in the money supply.

The money supply is flat in the recession of the early 1990s.

Then it really starts to take off as the dot.com boom gets going which rapidly morphs into the US housing boom, courtesy of Alan Greenspan’s loose monetary policy.

When M3 gets closer to the vertical, the black swan is coming and you have an out of control credit bubble on your hands (money = debt).

Greece used to have interest rates in the region of 18% with the Drachma.

The Euro came along and interest rates fell sharply, Greece started to borrow and spend, with the money creation feeding back into the general economy fuelling a boom. The same was happening in most Club-med nations and Ireland.

The financial sector had made an assumption that lending within the Euro-zone was like lending to Germany as Germany would bail everyone out and they set interest rates accordingly.

After 2008, it became apparent that Germany would not bail everyone out and interest rates rose. The borrowing booms came to an end and the repayments on debt overtook the new debt being taken out. The money supply started to contract in Greece, the Club-Med nations and Ireland.

This can very easily spiral into debt deflation as it did in Greece.

When the money supply is contracting, and the private sector isn’t borrowing, the Government is the borrower of last resort and the only party capable of keeping the money supply stable.

Austerity cuts Government spending and increases the rate at which the money supply contracts making things worse.

Richard Koo studied the Great Depression, Japan after 1989 real estate bust and the West after 2008:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

Ben Bernanke seems to be the only Western policymaker that took Richard Koo’s advice. He prevented the US from implementing austerity and going over the fiscal cliff.

Until other Western policymakers update their economics, the chances of them making good decisions are very close to zero.

Neo-liberalism’s flawed economics has turned the global economy into an empire of debt.

Before 2008 it was just the West that loaded up on debt, after 2008 the emerging markets have done the same thing.

Debt allows you to borrow money from the future and one day that impoverished future will arrive.

Central Bankers are already putting in trillions trying to stave off the debt deflation that is trying to take hold.

Their efforts can only maintain stagnation at present and there are still many asset bubbles that have yet to burst.

The sudden bursting of asset bubbles causes money destruction on bank balance sheets and a contraction of the money supply. Then debt deflation will take the upper hand.

Neoclassical economics destroyed itself in the debt deflation of the 1930s.

It’s going to do the same again.

Einstein’s definition of madness “Doing the same thing again and again and expecting to get a different result”

Debt based consumption and speculation, what could possibly go wrong?

The same things that went wrong last time.

Quite an interesting paper. This first reminded me the fiasco of Kenneth Rogoff with his public debt paper. He was rigth to identify debt as a burden but missed the target. Household debt looks pretty much the weakest domino piece of the debt game.

The starting point is brilliant:

This has been repeated here many times: standard macroeconomic models are useless. This paper does not say it but it is inferred from it. This study states that macroeconomic models not considering debt dynamics are particularly prone to fail in the mid and long term.

The finding that country-specific creditor protection frameworks heavily influence the effect of household debt on future growth pretty much reinforces the quality of the correlations they find.

Another finding is that:

The terms of trade do nothing to prevent slow growth after debt growth, so why focus on TTIP, TPP etc. as the “solution” for future growth?

Overall I find this findings more appealing than “secular stagnation”, or at least the definition of secular stagnation given by orthodox economists.

Thanks for that addition, Ignacio, which is so important in assessing the caliber of the writers and the source. I noticed a few years ago how BIS issues papers like this: sophisticated analysis informed by the tools available to academic Economics but not blinded by them. It is the only place I (almost) trust any more. I believed Rogoff, too, not because of their data, which everyone knows were to some degree fudged, but because of how they laid out, using history and common sense, the tools that would be used to keep institutional heads above water during the GEC: and sure enough, Financial Repression was one of the most important.

You don’t need a lot of facey data to realize that a high level of household debt will in the long term hurt growth. It’s common sense. There is a limit to how much debt a household can have.It varies by the income of the household. Borrowing for consume goods stimulates the economy at the time of the purchase. Eventually debt has to be repaid. When that time comes households that have no excess money to purchase no longer buy things. Since our economy and it’s growth is dependent on new consumption you reach a point where growth has to slow because of less consumption. Before the crash the population was maxed out with debt and couldn’t purchase or in many cases pay off their debt. Couple this with college graduates entering the work force already highly in debt and jobs scarce or lower paying, consumption crashed along with growth. That’s partly why the recovery is so slow. This new consumers were lower paid and strapped with high debt. They had no excess cash to consume. Until true wages grow the economy will continue to struggle. Typical republican economic policies like those proposed by Trump will only make things worse. Republicans fetish to eliminate all entitlements by privatizing them is why they implement the same old trickle down polices. They wan’t to destroy the economy which gives them the rational to get rid of entitlements. I believe republicans want the economy to crash to help them promote their agenda of screwing the little guy and transferring all of the wealth to the 1%. Neoliberal economic policy is their bible and wealth is their God.

Bad assumption. Economists don’t know what this common sense is you speak of. If cents were common, then rational people wouldn’t want them. Yet last year in Tangiers, while I was on my way to meet up with the Dalai Lama for some key lime pie, my Taxi driver interrupted our conversation to pull over and pick up a penny. Cents can’t be common.

What deleveraging?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=cSB3

Good graph. Makes it pretty clear that non-financial corporate is carrying the ball in terms of new debt creation (stock buy backs presumably). Following the trend for when households and non-profits had the ball before that came to a stop 2008.

And if there’s any de-leveraging it’s really been by the financial biz. Though that seems to have bottomed out in 2014 or so.

Household deleveraging. That’s what the paper is about.

I would think the US is a more unique case in the advanced category. I am sure we have the most extreme consumerist culture, the most extreme inequality, and the largest financial sector as a share of GDP, and these factors combine to create more flexibility in the growth and impact from consumer debt. From the end of the Volcker recession to the start of this crisis, the rate of HH debt growth was positive every year; excluding mortgage debt, only 1991 experienced a decline. The rate of growth spiked during the housing bubble, which certainly was unsustainable, and the sector certainly “delevered” from 2008-2011.

For the US, then, the change in HH debt is one of the key indicators of economic growth, and for the 25 years since 1983, debt growth was continuous. As Steve keen suggests about private debt in general, the acceleration (or deceleration) of debt is a good indicator of economic performance.

As some noted, student debt has been a main driver recently, but so too has auto loan debt, experiencing its own sub-prime bubble. If not restrained, the financial system will always find ways to meet Americans’ narcotic demand for debt. One of the reasons I’m willing to ride this Trump stock bubble longer is because of rising consumer confidence which almost always translates to rising use of debt and GDP growth.

I recently spent some time reviewing the Government’s 2016 financial report which was released in January. I was dumbfounded when I got tot he auditor’s letter and learned that the GAO can not issue an audit opinion due to material weaknesses across many agencies and branches of government. The DoD is evidently the worst and has not been able to produce audited financial statement for years.

“Although DOD was not able to issue its audited financial statements by the end of our 2016 audit completion date, it has consistently been unable to receive an audit opinion on its financial statements in the past.”

And Trump wants to give $54 billion in additional funds to an entity that can’t even count?

Why isn’t this a national scandal. Total outstanding debt went up by $1.4 TRILLION last year on a reported budget deficit of $550 million. And that is at the top of the business cycle. Something doesn’t compute and the GAO won’t certify the government’s statements. If a private entity received that kind of audit opinion its stock would be on the way to zero, it management would be fired and there would be a massive criminal investigation.

I don’t know when, but something has to give at some point. The idea that U.S. government debt is the risk free benchmark against which all other interest rates are set is absurd. This is going to be just like 2008. In September 2006 Moody’s upgraded Citigroup to Aaa. They should have been downgraded to triple F, double minus. We are living through a similar period of denial and delusions. There are always all kind of excuses and reasons offered up by our wisest financial pundits to explain that there is nothing to see here so just move along. There is no issue with massive deficits and money printing, all is well in the world’s most exceptional country, we are the strongest of the strong, the wisest of the wise and the richest of the rich. Debt doesn’t matter, in fact the more of it, the merrier!

Reading Jaques Rueff right now and this debacle has been brewing for over 50 years. Shocking how long such a dysfunctional system can last but it looks like it if finally nearly its endgame. But then again human idiocy knows no limits and if people think the dollar is strong it will be strong since it’s mainly a mental game. This isn’t physics or electoral engineering where the laws of nature always reassert the truth.

Robert: Do you (or anyone in the NC `peanut gallery’) have any idea when was the last time the GAO *did* manage to issue an audit opinion ? i.e. when was the last time the various agencies actually had their income/spending patterns understood ?

My guess would be that for the DoD the answer would be never or at least not since the Vietnam War. For other agencies probably not since the Bush tax cuts since they’d try to conceal the deficit increasing aspects – for their own agency – as long as possible.

We’ve pointed to this Cynthia McKinney video quite a few times. The Pentagon not being able to account for $trillions is not a new issue.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJK3RvkSJFg

I am sure that pushing this issue was what got her run out of Congress. Her fight with the guards would have been minimized in the normal course of events.

The DoD has a huge official black budget (I have to ask my tax maven for the name) and then it has the real black budget too.

Why do reps hate deficits? Because banks hate deficit spending, which competes with their own money creation that generates interest income.

Gov could provide all loans at low interest, such as previous existing post office banking, voted out as unfair competition to banks by dems and reps, as ordered by bank masters.

But deficits are only partially effective because of the self inflicted constraint that they must be borrowed from the private sector… the limited effectiveness is that investors’ money that wouldn’t be spent is used to employ those that will spend.

True deficit spending, money printing paid to spenders, would be somewhat more effective.

Deficits affect equities… falling deficits of recent years means relatively less investors’ funds go to bonds. Rising deficits mean less investors’ funds are available for equities… and this is beginning as a generational shift is occurring, less money flowing to 401(k)s even as retiring boomers begin to tap theirs… and, one might add, as prices and earnings become ever more detached…

Why do reps hate deficits?

I would argue it’s because it empowers them to make decisions about winners and losers, in particular when it comes to spending. “Honestly, we really wish we didn’t have to reduce spending on X, but my hands are tied; it’s the deficit don’t you know”.

Imagine if the Fed Gov had the power of the printing press directly in its hands (a la what Lincoln did with the greenback). Makes it more challenging to say your hands are tied. That’s when you worry about inflation. [And even then, that’s only when the Fed Gov gets irresponsible and drops the ball on managing the money supply through taxes and bond issuance.]

Contrast to what we have now, where the Fed Gov doesn’t really have the power of the printing press in its hands. At best, the Fed Gov can only recycle the monetary base out of the hands of the wealthy who have it hoarded back into the economy. Which should increase the velocity of money which should have some salutary effect on inflation. But that stimulation to inflation pales mightily to the damage that can be done from the liquidity pump of the Fed Reserve feeding the latest bubbles. If you want real inflation in today’s status quo, it’s a function of that liquidity pump every time.

Mosler point is that Qe is deflationary because it reduces interest payments from public to private sector. But removing the option of owning treasuries means savers look for other investments, since Gfc equities and houses, resulting in bubbles as you say and as intended, in the former. But Qe has stopped, only thing keepingbequities inflated are bank loans to companies to buy their own stock. This petering out, too.

Agreed savers buying treasuries funding deficits just shifts money to those who will spend, but it also reduces equity purchases.

Reps are happy to fund weapons. IMO they would be happy to fund any spending their donors want. Donors don’t want entitlements, and infra apparently too defuse to attract big enough donations to catch their attention.

Thank you NC. Great post and comments. The excerpt from ECONNED was the parable of our times. “XCrop” indeed. As the almost-brain-dead Nancy Pelosi said, we can’t have single payer health care because “We are a capitalist country.” And we send these nitwits to represent our interests. So this line of brain-dead thinking carries throughout everything we do. Can’t have government-paid college education because “we are capitalists”. Jesus god. We are keeping the finance industry on luxurious life support. End their exorbitant privileges now. End the Fed. Make the Government the lender of first resort for all things socially important. It is our sovereign right. Better yet, hang the entire finance cabal by their heels. Let them twist in the wind.

Susan, since “we are a capitalist country”, how is it that we have low fee based sewage treatment? That is a health issue too. How is it that sewage treatment has never been privatized AFAIK?

———–

Author,

What about the unmentioned economic effects of X-Crop since it is a GMO and is undoubtedly patented, which means more and more income flows to the patent holder from farmers, consumers and governments that grows the stuff, versus seed saving cheaper or free natural varieties?

Cast iron, 100%, take it to the bank (or maybe not) fact:

A public sector debt is equal to the penny of a private sector surplus

In spite of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, the enduring genius of neoliberal economics is the fact that it is still successful in winning the arguments in the minds of most electorates in advanced economies across the globe.

Ironically it is still widely viewed as the one and only, albeit imperfect, ‘ideology’ of sound money management and the most efficient allocator of resources based on the lie that there is a supposed free, sometimes chaotic,yet functioning market underpinning this unsustainable financial charade working to deliver the best possible harsh but fair outcomes.

Running a nation’s finances as one would a household is a mostly fallacious narrative, particularly in advanced sovereign economies, but an indispensable one for self-serving neoliberals, and one that makes most sense to most voters when trying to convince them that their well meaning elected representatives are in the invidious positions of making these tough calls to reluctantly try and ‘balance the nation’s books’ on their behalf.

No wonder some ‘enlightened’ supposedly fiscally conservative politicians are so keen, in private at least, to whisper, ‘learn to love the debt’ whilst publicly decrying it, when so much of it is created either to directly benefit its own constituency through QE or tax breaks for example or indirectly by saddling hardworking, increasingly impoverished people with as much debt as possible to ensure they keep their heads down, keep grinding away and keep paying the interest and taxes to reduce the money supply in order to further reduce the potential financial burden on what is laughably still known, without a hint of irony, as ‘the wealth creators’.

And then to add insult to injury we’re told that this unearned surplus held by the wealthy is healthy as it will be spent in the economy and will gradually trickle down to everyone’s benefit!!

‘Nice work if you can get it’ as the old song goes eh?

The best way I can think of to show that Fed Gov debt should not be guiding decision making is to look at how it would operate under a cleaner MMT regime, one where the Fed Gov operates the printing press. I’m thinking the greenback scenario, where the Fed Gov wasn’t a liquidity pump (a la fractional reserve banking), but rather where the Fed Gov simply spends money into circulation.

In that scenario, there’s only three levers to manage the money supply:

1) cap what you print

2) keep printing and then tax money out of circulation

3) keep printing and then swap bonds with those who have hoarded up the money spent into circulation.

The 3rd option means selling bonds to the winners. And they’ll gladly part with their currency. Because if they had something better to spend it on, they would no longer have currency in their hands. Nobody wants to be holding currency; there’s always something that yields yield. And the Fed Gov bond is the yield of last resort; it doesn’t matter how big or small the yield is.

And the Fed Gov can keep this up, swapping bonds with the winners til the cows come home because the Fed Gov can print the currency that pays out the interest. But it doesn’t matter, because the bond holders will just buy more bonds with that interest. Again at the end of the day they don’t want to be holding currency. And once the bond holder sends the currency that was earned as interest back to the Fed Gov, it becomes basically extinguished. That’s the whole point in having the printing press for bonds; the issuance of bonds by the Fed Gov is to take currency out of circulation. But it means a never-ending growth of bonds. And nobody will say boo in this scenario. It represents the hoarded wealth of the winners.

Now compare to what we have now-of-days. The key difference is that the Fed Gov can’t print the currency to pay out the interest. So the Fed Gov has to find other avenues to pay the interest instead of printing money. But otherwise the scenario is exactly the same. The entity receiving the interest will just plow that interest right back into more Fed Gov bonds. And one can say that they’re effectively buying the bonds that were used to pay the interest in the first place. [For a fiction, one has to pretend the Fed Gov just needed to float the bond for an interim until the interest paid out came back in to purchase the bond that needed to be floated.]

I agree but I wouldn’t characterize your proposal as “a cleaner MMT regime”. It flies in the face of MMT philosophy where the market determines the creation of money via banks. Your approach is clearly addressed in the monetary reform movements such as embodied in the 2012 Kucinich National Employment Emergency Defense Act HR 2990. Its not just a difference of opinion on mechanics but a deeper philosophical difference – can the People be trusted – MMT….no.

Same old procedure to pay bond interest and keep control of the Fed rate just make use of “deactivated money” (taking money out of active circulation through savings schemes like government securities):-

http://heteconomist.com/exercising-currency-sovereignty-under-self-imposed-constraints/

Can apply a holding limit of course but Federal government has delegated and prime responsibility for containing inflation and doesn’t always make a good job of it.

Who would have believed that increasing the size of the parasitical rentier economy would have negative effects on the productive/consumption economy ? Adam Smith ? Poor old Adam — he only gets wheeled out when it suits the TPTB.

Aren’t most people masochists and carry on voting for the politicians who screw them rather than make an effort to understand economics and monetary systems in particular? You know like working out money is a double-edged sword like fire, for example.