Yves here. Readers, brace yourselves for an influx of ideologues who haven’t bothered to read the article and/or straw man it. I hope you are up for the challenge!

By Edwin G. Dolan who holds a PhD in economics from Yale University. He has taught in the United States at Dartmouth College, the University of Chicago, George Mason University and Gettysburg College. From 1990 to 2001, he taught in Moscow, Russia, where he and his wife founded the American Institute of Business and Economics (AIBEc), an independent, not-for-profit MBA program. Follow him on Twitter: @dolanecon. Originally published at Niskanen Institute; cross posted from Evonomics

Economists, libertarian economists included, love to measure things. The Human Freedom Index (HFI) from the Cato Institute is a case in point. Its authors have assembled dozens of indicators of personal and economic freedom. They invite interested researchers to use them to explore “the complex ways in which freedom influences, and can be influenced by, political regimes, economic development, and the whole range of indicators of human well-being.”

I am happy to accept the invitation. This post, the first of a series, will take a first look at what we can learn from the data about the relationships among freedom, prosperity, and government. The relationships turn out to be not quite as simple as many libertarians might think.

The Data

The Human Freedom Index consists of two parts. One is the Economic Freedom Index (EFI) from the Fraser Institute, which includes measures of the size of government, protection of property rights, sound money, freedom of international trade, and regulation. The other is Cato’s own Personal Freedom Index (PFI), which includes measures of rule of law, freedom of movement and assembly, personal safety and security, freedom of information, and freedom of personal relationships. The Cato and Fraser links provide detailed descriptions of the two indexes.

In order to explore the way freedom influences other aspects of human well-being, I will draw on a third data set, the Legatum Prosperity Index (LPI) from the Legatum Institute. The LPI includes data on nine “pillars” of prosperity, including the economy, business environment, governance, personal freedom, health, safety and security, education, social capital, and environmental quality

The EFI and PFI cover 160 countries and the LPI 149 countries. In this post I will use the set of 143 countries for which data are available in all three indexes. The Cato, Fraser, and Legatum links above provide detailed methodological information.

Economic and Personal Freedom

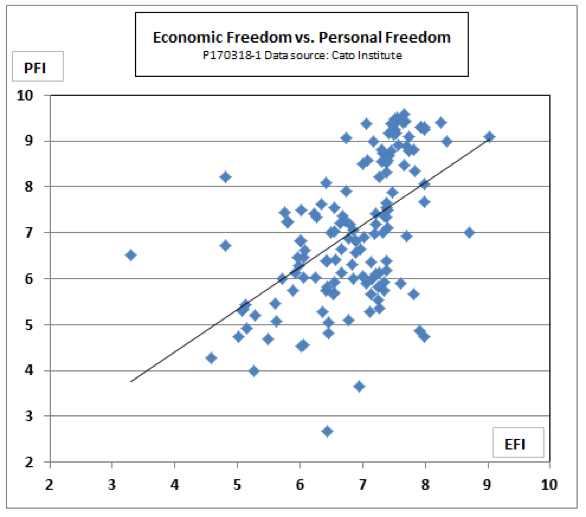

We can begin by confirming a result reported in the introduction to the Cato Human Freedom Index, namely, that economic freedom and personal freedom are closely related. Expressing both indexes on a scale of zero to ten, with ten indicating maximum freedom, a scatterplot of the two indexes looks like this:

The correlation coefficient between EFI and PFI for the 143 countries in the joint Cato-Legatum sample is 0.53—not an especially tight relationship, but statistically significant. The slope of the trend line is 0.91, meaning that each one-point increase in the EFI score is associated with a 0.91 point increase in the PFI score.

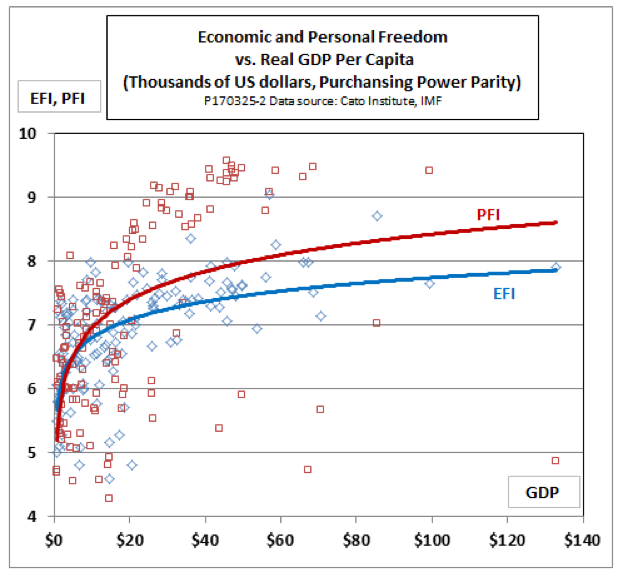

The relationship between economic and personal freedom is partly explained by the fact that both are positively associated with income. As the next chart shows, that relationship is nonlinear for both measures of freedom. The log of real GDP per capita, expressed in U.S. dollars at purchasing power parity, provides a reasonably good fit. The correlation coefficients are 0.51 for log GDP and the personal freedom index, and 0.56 for log GDP and the economic freedom index.

Using multiple regression analysis, we can recalculate the relationship between economic freedom and personal freedom in a way that controls for their common relationship to GDP. Taking GDP into account increases the correlation coefficient between the two aspects of freedom from 0.53 to 0.59, but it also reduces the slope of the relationship between PFI and EFI. Each one-point increase in EFI is now associated with a 0.61 point increase in the PFI rather than the 0.91 point increase that was estimated without including GDP. All of these results are statistically significant at a 0.01 level of confidence.

So far, so good. We have found that personal freedom and economic freedom are positively associated with each other, and that both freedom indexes are positively associated with prosperity as measured by real GDP per capita. Good libertarians should expect these results and be gratified to find them confirmed.

Freedom and Prosperity

The previous section showed that economic and personal freedom are positively related to prosperity as measured by GDP per capita, but prosperity is more than GDP. Libertarians tend to see freedom as also conducive to other aspects of human well-being, such as education, health, and personal safety.

There are many measures of prosperity and well-being available. I hope to be able to explore several of them and their relationships to human freedom in future posts. In this introductory treatment, however, I will limit myself to the education, health, and personal security indicators from the Legatum Prosperity Index. In what follows, I will refer to the average of these three Legatum “pillars” as the education-health-safety index, or EHS, measured on a scale of 1 to 100. (By and large, the results reported below also hold for each of the three indicators considered separately, although some of the individual coefficients are not statistically significant.)

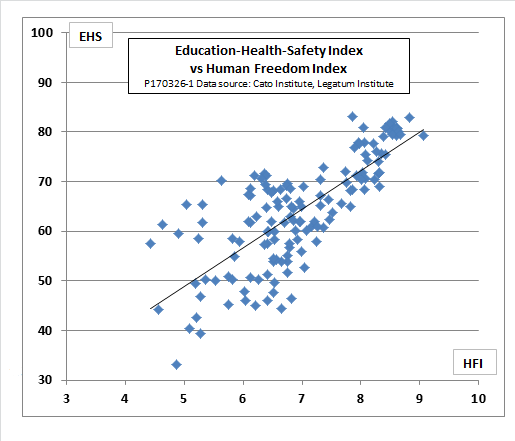

We can begin, as before, with a simple scatterplot of EHS and HFI:

As the chart shows, the relationship between the two variables is positive and strong. The correlation coefficient of EHS and HFI is 0.76. Each of the individual freedom components also correlates positively with EHS, although not quite so strongly: 0.68 for economic freedom and 0.67 for personal freedom.

Since EHS, HFI, and GDP per capita all correlate strongly with per capita GDP, we need to be cautious about interpreting the simple correlation coefficients. For example, it could be that the apparent correlation of EHS with EFI simply reflects the fact that rich countries tend to have good schools, hospitals, and police forces, but that people in rich countries that are free live no better than those in rich countries that are unfree.

We can, again, set our minds at rest by using multiple regression to sort out the individual contributions of each variable. A regression of EHS on EFI, PFI, and the log of GDP per capita yields a strikingly strong result. The overall correlation of EHS and the three variables is an impressive 0.91. Using the coefficient of determination, R2, we can interpret that result as meaning that the three variables jointly explain 83 percent of the variation in education, health, and safety among countries. The contributions of each of the individual independent variables are positive and strongly statistically significant.

It seems, then, that human freedom in both its economic and personal manifestations contributes positively to human well-being as measured by data on education, health, and personal safety—another result sure to please libertarian readers.

The Effects of Size of Government on Freedom and Prosperity

Things get more interesting when we dig a little deeper into the reported linkages between personal and economic freedom by breaking the Fraser Institute’s EFI down into its separate components: size of government, protection of property rights, sound money, freedom of international trade, and regulation. When we look at the simple correlations between the personal freedom index and the EFI components, we find they are all are positive, as expected, except that for the size of government (SoG), which is negative. The correlation of SoG with the personal freedom index is -0.16. Remember that for all components of the EFI, a higher value means more freedom, so the negative coefficient means that a larger government is associated with greater freedom. That is not what most libertarians would expect. Is this just an anomaly or a real statistical regularity?

As a first step toward answering this question, we need to see just what the SoG indicator really measures. SoG is itself a composite derived by averaging four subcomponents: government consumption expenditures, government transfers, marginal tax rates, and something called “government enterprise and investment” (GEI), which is Fraser’s name for the ratio of a country’s government investment to its total investment. Examining these subcomponents uncovers two problems.

One is that only the government consumption indicator is available for all countries. Data on transfers, tax rates, and government investment are missing in several cases. Where data are missing, the SoG measure is the average of the components for which there are data. This approach to handling missing data degrades the statistical power of the SoG indicator as a whole.

By analogy, suppose that we want to assess the health risks facing a city’s residents using their body mass index (BMI), their gender, and their age. To measure BMI, we need to know each person’s height and weight, but suppose we are missing the data on weight for some individuals. Rather than leaving those people out of the sample, we could estimate their weight by using the average weight for a person of a given height, age, and gender. However, that procedure would inevitably make our assessment of health risks less statistically reliable than it would be if we had had complete data for everyone in our sample.

The second problem with SoG is that its GEI subcomponent has a strong negative correlation with the other three subcomponents—government consumption, transfers, and tax rates. Also, if we look at the relationships of the SoG subcomponents with independent variables, such as GDP, GDP growth, health, education, and safety, we find that the correlations for GEI are positive whereas those for the other components are negative. Creating a composite indicator out of subcomponents that correlate negatively with one another and that have opposite relationships to independent variables is a statistically dubious procedure.

Again resorting to analogy, suppose we want to devise a composite indicator of heating efficiency for residential buildings. We know that the size of a building’s windows and the thickness of its walls are relevant variables, but how to combine them? Simply averaging the thickness of the walls of each building and the area of its windows would not give us a reasonable composite indicator, since the two variables have opposite effects on heating efficiency. A house with small windows and thick walls could have the same score as one with large windows and thin walls, even though the former would be far more efficient than the latter. Instead, either we should treat windows and walls as separate variables in a multivariate analysis, or, if it is important to have a single compound indicator, we should reverse the sign on window area before combining it with wall thickness.

My guess is that the people at Fraser who created the economic freedom index never thought about this problem. More likely, they used ideological rather than statistical criteria in formulating the SoG indicator. They probably assumed, a priori, that higher taxes, more government consumption, more transfers, and more government investment all make us less free, and accordingly, assumed that an average of the four would make a good measure of the size of government for their economic freedom index. The result is statistical mush.

None of this means that the size of government is unimportant. It suggests, instead, that Fraser’s SoG indicator is not a statistically sound measure of the size of government. We can check that by comparing SoG with a simpler measure based on the ratio of total government expenditures to GDP, which we will abbreviate as SGOV. The required data are available for all countries in our sample from the IMF World Economic Outlook database. For easier comparison with SoG and with other components of the EFI, I express SGOV on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating the smallest government. (Specifically, if G is the ratio of government expenditure to GDP as expressed by the IMF on a scale of 0 to 100, then SGOV = (100-G)/10.)

The SGOV indicator turns out to have much more explanatory power than Fraser’s SoG. The correlation of SGOV with the log of GDP per capita is -0.48, compared with -0.25 for SoG. Both correlations suggest that higher levels of GDP are associated with larger government sectors and both coefficients are statistically significant, but the association is stronger for SGOV, derived from the simple ratio of government expenditure to GDP, than for Fraser’s original SoG indicator.

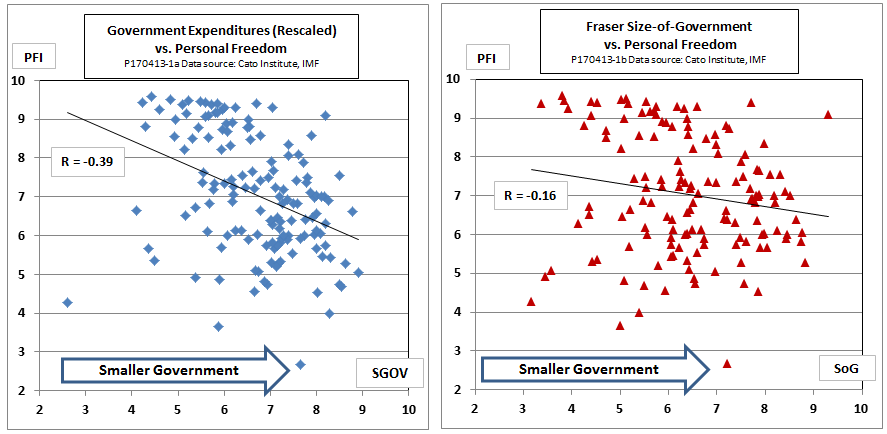

Turning to the personal freedom index, the simple correlation of SGOV with PFI is -0.39, compared to – 0.16 for SoG. Both indicators suggest that personal freedom increases as the size of government increases, but the coefficient for SGOV is larger, and it is statistically significant, whereas that for SoG is not. Here are scatter plots for the two measures of the size of government vs. the personal freedom index:

As in earlier cases, we should not rely solely on the simple correlation, which is attributable in part to the fact that both the size of government and personal freedom correlate strongly with GDP per capita. We can get a more accurate picture by using a multiple regression to control for GDP. A regression of PFI on SGOV and the log of GDP per capita shows a correlation of 0.53, with all coefficients significant at the 0.01 level. The slope estimate indicates that on average, a one point decrease in SGOV is (that is, a one-point movement toward larger government) is, on average, associated with a quarter-point increase in personal freedom.

As a further test of the relative statistical power of the two indicators, I ran a multiple regression of PFI on both SGOV and SoG, plus the log of GDP per capita. When both measures of the size of government were included, the relation of SGOV to PFI was positive and statistically significant but SoG had no statistically significant relation to PFI.

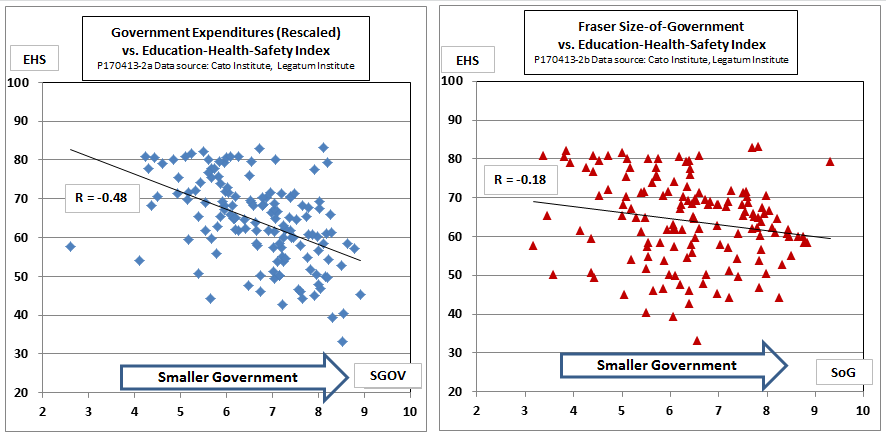

Finally, I got similar results when I used the EHS measure of prosperity as the independent variable. The correlation coefficient for EHS and SoG is -0.18, indicating a tendency for larger government sectors to be associated with greater prosperity, but the absolute value of the coefficient is too small to be statistically significant. The correlation of EHS with SGOV is -0.48. In this case, the value of the coefficient is statistically significant and the negative sign again indicates a tendency for countries with larger governments to have higher scores for education, health, and personal safety. Here are the scatterplots:

As before, we can refine the results from the simple correlations using a multiple regression, controlling for GDP per capita. Doing so shows that SGOV, the ratio of government to GDP, has a negative and statistically significant association with EHS, showing that larger government is associated with higher levels of education, health, and personal safety. However, SoG, Fraser’s size-of-government measure, has no statistically significant association with EHS.

Conclusions

Our statistical investigations lead to two substantive conclusions:

- First, the data appear to support notion that economic freedom makes a positive contribution to personal freedom and prosperity. That holds true whether we measure prosperity in a narrowly economic sense, as GDP per capita, or in a broader sense, using noneconomic indicators of education, health, and personal safety.

- Second, the data do not support the notion that a larger government is necessarily detrimental to either freedom or prosperity. On the contrary, countries with larger government sectors tend to have more personal freedom and higher indicators of education, health, and personal safety.

These findings suggest that libertarians need to do some further thinking about “Our Enemy, the State,” as Albert Jay Nock expressed it in the title of his classic book.

Countries grow rich because they adopt policies that enrich the society, and remain poor when they enact policies meant to enrich and entrench the elites. The more power the general population has, the more you get the former, because enriching the entire society is the only way the masses can grow richer. And if the masses have power over the state, they also support a large and powerful state, as it serves them.

Undemocratic countries are poorer as the elites benefit most from robbing the population and may even destroy productive assets to weaken the power of the working people. As the state is a tool of elites, the general population tries to avoid contributing to it and does not support it, making the state weaker and smaller.

Fair enough, as far as it goes…but I have a hard time taking any analysis all too seriously when they’re using statistics such as the ridiculous Economic Freedom Index and per capita GDP.

It’s also unclear to me who this piece is aimed at. The author seems to think that rationality has some place in public policy formation — which is kind of cute, but totally naive. You’re not going to convince Libertarians to push for a larger state apparatus with this kind of argument (or at least not many), the conservatives already want a big (military) budget, and as for the rest of us, this is just superfluous: we already want a bigger (social spending) budget…just sayin’.

Some people don’t have a strong opinion either way. They may have a lukewarm opinion about the value or harm of big government, but they aren’t ideologues. Those are the people who might be persuaded to change their thinking by something like this article.

Yeah, maybe…I just can’t get super-excited by economic analysis that makes the same unjustifiable assumptions as the orthodox theologians…er, economists. Higher GDP = Good is a bad assumption, for one, so starting your analysis with that is a starting out all wrong, imho, regardless of whether or not I approve of the conclusion one reaches.

And I think the real political question isn’t big gov’t or small, but rather what our big gov’t should be spending on. Seems that Republicans have no problem with big gov’t, just so long as it’s big on “defense.”

yes and these statistics did focus on health, education and welfare; but left out the abuses of organized military power… which are commonly believed to destroy empires. So the take away is, if it is true that abusing military power does destroy civilizations (which I assume is true because it is always such a waste of everything), big military (which also goes along with big gov) is counterproductive to freedom and prosperity. All that was left unsaid.

Where is the assumption that high GDP is good? The article specifically says that “prosperity is more than GDP”, and compares the size of government to other factors. It’s not stone cold proof that big government is always superior (which the article didn’t claim) but I think it is still useful information especially for those who don’t already have strong feelings about the issue.

The “Economic Freedom Index” is preposterous propaganda. It measures “the size of government, protection of property rights, sound money, freedom of international trade, and regulation”? I tend to note how “freedom of international trade” needs thousands of pages of trade deals and treaties to be free, and “protection of property rights” is the biggest and most far reaching set of activities of law, courts, and enforcement. However, none of this counts as “big” government, not like, say, stopping a factory from dumping poison in the river, or paying teachers.

So you start with a definition that says “big” government is government that provides for the welfare of the majority of the people and “limited” government is government that has much more far-reaching power and activity, mostly devoted to enforcing the power of the rich. I bet the rest of the definitions and assumptions share the ideology.

Agreed.

“Sound money” means what, exactly? Probably not an approach to monetary policy that serves the majority of the populace by, say, directly funding a job guarantee program.

I suspect “sound money” is meant to mean something other than runaway inflation or deflation. But maybe “sound money” really means the extent to which elites and their pals can rig markets. Or put pals in place in central banks to make friendly adjustments to monetary supply. Or control the funding & policy decisions dictated to other countries by world banks (IMF, WB etc.) (i.e., ensure there is no chance of a level playing field, ever)

This article reminds me of that most ideal and wonderful of all statements about what our government should be: the Preamble to the Constitution:

““We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

We the People…….that’s a pretty big government!

Do you see anything in the Preamble about the right to get filthy rich? Or perhaps protection of corporations at the expense of everything else? Or perhaps “Corporations are people too?”

I think the truth has been staring us in the face in this country all along but most of us have had the blinders of greed and self interest strapped onto us from a very early age….

And yes before anyone attacks, I know the Preamble was written as just a pretty piece of idealism that the Founders really didn’t believe in themselves, but it is still a remarkable and true statement. We the People have to be the government in order to “form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”

I am glad there are economists like Edwin Dolan who are pointing out that the emperors of neoliberalism who have tried to sell us that the opposite of the Preamble (it’s not the people who should rule, it is the wealthy, affluenza is defense against criminal behavior, domestic tranquility arises when people are serfs, common defense means harming as many of your neighbors as you can, general welfare is tax money for corporations, and Liberty belongs to the few) is the truth, have no clothes….it’s all smoke and mirrors…..

Too bad everything BIG is always run by the sociopaths.

I guess the “BIG lovers” will never get this “concept”.

that may be, but until all big corporations are abolished, it’s quite utopian with little to do with existing reality. First we really do need to get rid of corporations.

+1000

I am curious as to your proposal, then, for administering to anything BIG. If we break something BIG into smaller pieces and then administer to those, the whole is still BIG and the collective administrations are, themselves, BIG.

Your reply is not a counter-argument, it’s a total non-sequiter. I don’t disagree about the sociopaths bit, but it’s not going to convince anyone the way it’s presented.

Divide and conquer- divide the BIG into smaller pieces and the whole might still be BIG, but in order to use their economy of scale they must agree to take similar courses of action. It makes using that concentration of power more difficult, but not impossible.

I get proper worried when I see an article which is willing to use regression analysis to turn noisy data into something simple and digestible. Regression analysis has a place, and it is a very, very narrow place. I’m speaking as a geologist here, but I’ve noticed this crap spreading to all the sciences. Regression does not do the thinking for you, math does not do the thinking for you.

If I were to take the data and throw it through some different filters, I could get the answer I want. I could get any answer, including nonsense answers. I know this because I’ve done that (by mistake) and luckily wasn’t stupid enough to believe what the numbers were telling me.

I say this even though I agree with the underpinning argument of the article. I am not contesting the article’s conclusions, I am contesting its reliance on this methodology. I just know some Libertarian/Small-Government-Conservative/Pick-your-label is cooking up a counter-article which is going to use similar statistics with a different methodology to prove the exact opposite. There will be nice regression lines and charts that indicate that, yep, small government is the best thing ever!

My first reaction to these correlations was that it clearly discredited the old claim that freedom and equality are always at odds with each other and each reduces the potential prosperity of the other. But one problem with the conclusion that economic freedom promotes prosperity and big government promotes that freedom is that we are in direct confrontation with an immovable force when it comes to the cherished freedom to be prosperous: the environment. And we might need to redefine prosperity at some point. Relatively soon. Big government can certainly help do that.

I don’t want an infinitely large government.

I only want a government large enough to protect me from those who are currently free to drown me and mine in

debtthe bathtub.“Big” reminds me of the day I stopped listening to Tyler Cowen. He was doing an interview, and mentioned that he wasn’t against regulation, but he was against too much regulation. As though perhaps 4 regulation would be all right, but 7 regulation would be right over the top. This is pointless. Eddie Izzard demolished this style of thinking in his brilliant sketch Toasters and Showers (This is not 5 toast!)

The whole use of regulation is in what it does. Regulation is meant to encourage specific kinds of behavior, or to discourage others. The change in behavior is the only point. The amount of generic “change” isn’t worth thinking about. Content is the important feature of regulation. Content matters.

Ditto with government. What it does is the thing we care about. Consider a small government that concerned itself only with narcotics, prostitution, and gambling. Ewww, right? Now imagine a big government that concerned itself with narcotics, prostitution and gambling. What’s to prefer?

Wow, the holes in the analysis are so big you can drive a truck through it. Their SGOV measure is ratio of government expenditures to GDP, but that government expenditure is not sample controlled. What is included in government expenditures? National health care, education in countries with those systems? How do you compare those with countries with privatized health care and education, where nominal government expenditures are lower.

Correlation are pretty poor to start with, so it could easily be correlation of health/education for countries that provide it subsidised/free, hence better outcomes and higher spending.

I think the author is trying to hoist the Cato types on their own petard, and therefore is playing this straight up for that to work, as in taking their methods and assumptions as a given and showing the picture isn’t as tidy as they would like the public to believe. But as you point out, he undermines his cred with other audiences by not raising other caveats about their methods.

^ This.

I’m not seeing a difference between GDP per capita and per capita GDP.

If the two are equal then the quoted phrase means “since x, y, and z all correlate strongly with z…”

I agree that EFI and GDP are bogus. I can dump a big barrel of toxic waste into a school bus and GDP gets boosted up. Someone has to pay the hospital bills for the victims, someone has to haul the bus off to a junkyard, etc. It’s a broken windows kind of prosperity. If you inflict a lot of chaos and damage and misery on the world, you have probably boosted GDP by quite a bit.

The problem is that a libertarian might define freedom as “the ability to run my plumbing contracting business without having the government taxing me, or being subject to regulations” which is a pretty dismal conception of freedom.

Meanwhile I might define freedom as “only working two or three days a week and still having access to healthcare, so that I can spend the rest of my time reading, sitting on the beach, or playing music with no commercial appeal for my own amusement.”

I might define freedom as being able to take care of myself, and also being able to take care of the people I love when they need it. People I love include family, friends, neighbors, and people around the world I haven’t even met yet.

“Taking care” — of oneself and others, covers a lot of territory (like the earth & its atmosphere), and I think freedom should, too.

… and of course there’s my freedom from having my house flooding caused by burst pipes fitted by an unregulated, incompetent plumber using crappy out-of-spec – probably counterfeit – materials.

Let me see if I understand this:

Government spending is one factor of GDP, and smaller government spends less money. Lower government spending leads to lower GDP and therefore lower GDP per capita.

If higher per capita GDP equates to greater freedom (author’s argument) then lower GDP per capita equates to less freedom. Therefore, smaller government equates to less freedom.

Isn’t this circular logic and begging the question?

This is actually not correct.

Your argument is that the quantity of government spending is logically correlated with GDP, and that GDP is correlated with the freedom metrics the author uses. If the author was using the quantity of government spending as the measure of “larger government,” your logic would be airtight.

However, the author uses instead a measure (SGOV) that is a function of the ratio of government spending to GDP, so the issue that you are worried about does not come up.

There might still be a related problem, though – what if SGOV is still correlated to the size of GDP, i.e. what if countries with a larger GDP tend to have a larger percentage of their GDP devoted to government spending? In fact, this is (according to the author) true; however, he anticipates the problem – see the sentence:

In other words, disaggregating the effects of SGOV and GDP still results in SGOV being significant in the resulting regression.

This post’s fundamental mindset adds to our dystopia. Other commenters have addressed some of the problems (e.g., that GDP thingy). I’d like to point out several more problems/omissions.

For example, the focus is on quantity and no measures of quality. Doing “what”–specifically–really matters. And who measures the value of the “what”, and how? (Does spending on any kind of education = a presumed social benefit, just because money is moving into someone’s pocket?)

Notice the lack of focus on distribution of quantities across society! GDP is already bogus, then take the bogusosity to the next order of magnitude when using it to calculate GDP per person. Like, what if one person has virtually all the GDP, and the others almost nothing?

No mention of how much/little said government actions reflect the wishes of its citizenry. In the USA, there’s about zero correlation with public preferences, according to the research; but there’s a strong positive correlation with the policies that elites want.

No mention of how decisions are made, and its impact on the other factors. E.g., consider USA’s representative (not!) democracy (not!) using bizarre rules and majority-style votes and backroom pork barrel parties, with horsetrading done by corrupt individuals who couldn’t even qualify as a candidate unless they were corrupt/controllable, and able to raise huge sums from vested interests as proof.

The starting point of this post–the world view and mindset–is fatally flawed. It offers no meaningful insights for human society, and it does worse than that by suggesting that it does! Too many important pieces have been omitted, ensuring that any image formed by cobbling together the kinds of statistics used, has no relationship to the real world.

In sum, larger govt generally results from more democracy in our capitalist world as democracy is the only way to control the excesses of the ruling class. Greater democracy will correlate with certain kinds of economic freedom such as the ability to form unions or, in more extreme and preferred form, to avoid working for someone else (Scandinavian countries always do well on entrepreneurship measures as a social safety net encourages this type of freedom). Also, more democracy encourages greater social freedom from excessive accumulation by some–e.g., through progressive taxation. This works in part through Locke’s dictum (ignored by Locke) that there should be enough resources for all without impinging on the freedom of others which is contrary to excessive accumulation. Looking at it from the other side, when unrestrained excessive accumulation allows some people to employ others or even worse to use their accumulation to control govt so that they can form powerful organizations (such as corporations) with other accumulators like themselves to restrict the freedom of others.

More indirectly, to maintain control of govt and society in general requires the expansion of unproductive organizations and activities and the proportion of workers doing unproductive work, such as propaganda (media and advertising) and social control (policing [including private policing], military, and media) mindless circuses (“entertainment”), and unproductive services that are offspring of excessive accumulation (FIRE).

These concomitant factors mean that even the most democratic societies will face externalities requiring them to limit freedom in response if there is a very strong govt that sets the agenda for the rest of the world.

AJ Nock’s main idea is that coercive govt drives out what he called ‘social power’. That latter is identical to what deToqueville observed and called ‘civic associations’. Americans use associations to give fêtes, to found seminaries, to build inns, to raise churches, to distribute books, to send missionaries to the antipodes; in this manner they create hospitals, prisons, schools…In America I encountered sorts of associations of which, I confess, I had no idea, and I often admired the infinite art with which the inhabitants of the United States managed to fix a common goal to the efforts of many men and to get them to advance to it freely.

It’s hard to dispute Nock’s point. When Nock wrote his book, there were 130,000 school governance authorities in the US – with each requiring a dozen or more part-time volunteers from the community to manage it. A huge portion of adults had SOME experience in actually being on a school board. Today there are 12,000 ‘school districts’ – all run by full-time ‘professionals’ and the only allowed wider responsibility is to vote periodically and pay taxes. Not only are those professionals inclined more coercively; those who vote and ‘keep them accountable’ are now ignorant. And no matter what the social arena, the problem is the same.

It is a strawman to conflate the effects of big coercive government. It is NOT generally on the individual in isolation. It is on the ability/freedom of individuals to work together in association to solve problems they can see that affect them.