After having promised banks to get rid of Dodd Frank, which was never a strong enough bill to have a significant impact on profits or industry structure, Trump didn’t even back the House version of the bill to crimp Dodd Frank. But you’d never know that from the cheerleading from bank lobbyists upon the release of a 147 page document by the Treasury yesterday, the first of a series describing the gimmies that the Administration seeks to lavish on banks. As we’ll touch on below, the document repeatedly asserts that limited bank lending post crisis to noble causes like small businesses was due to oppressive regulations. We wrote extensively at the time that small business surveys showed that small businesses then overwhelmingly weren’t interested in borrowing and hiring. Businessmen don’t expand operations because money is cheap, they expand because they see a commercial opportunity.

But the even bigger lie at the heart of this effort is the idea that the US will benefit from giving more breaks to its financial sector. As we’ve written, over the last few years, more and more economists have engaged in studies with different methodologies that come to the same conclusion: an oversized financial sector is bad for growth, and pretty much all advanced economies suffer from this condition. The IMF found that the optimal level of financial development was roughly that of Poland. The IMF said countries might get away with having a bigger banking sector and pay no growth cost if it was regulated well. Needless to say, with the banking sector already so heavily subsidized that it cannot properly be considered to be a private business, deregulating with an eye to increasing its profits is driving hard in the wrong direction.

Nevertheless, despite faithfully repeating dubious bank taking points, the Treasury document isn’t as far-reaching as the headlines would have you believe. First, for the most part, it seeks to weaken already underwhelming post crisis reforms rather than undo them entirely. Second, the Treasury finesse is to focus on making changes that for the most part don’t require legislative approval. But even that isn’t likely to happen soon with Trump not having taking control of many parts of the bureaucracy. And some regulations aren’t easy to change.

For instance, banks actually do have some legitimate grounds for complaining about the Volcker Rule, and the Treasury devoted a section to it in this document. While its goal of not having the government support speculative trading by banks is correct, the idea of trying to draw a line between customer and proprietary trading was misguided. Banks routinely take positions to facilitate customer trades, and a “customer trade” can easily be gamed.

However, the bogus justification for weakening the Volcker Rule is that it has reduced market liquidity. First, that is merely (and always) asserted; the Fed hoovering up the most liquid securities, and the ones most often used for repo financing, namely Treasuries and top rated mortgage backed securities, played a big role. And more important, highly liquid markets are not necessary for commerce or investment. They are very useful for short-term speculators. Former Goldman partner, now Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, debunked that notion in 2015. From a Reuters article:

Carney, in a speech Wednesday, argued that reduced market depth and higher volatility are part of a process with “further to run.”

“To be clear, more expensive liquidity is a price well worth paying for making the core of the system more robust,” Carney told an assemblage of City of London bankers at the Mansion House.

“Removing public subsidies is absolutely necessary for real markets to exist. Volatility characterizes such real markets and much of the pre-crisis market-making capacity among dealers was ephemeral.”

By contrast, anyone who understands how trading markets operate will recognize that this statement from the Treasury document is incoherent:

Maintaining strong, vibrant markets at all times, particularly during periods of market stress, is aligned with the Core Principles and is necessary to support economic growth, avoid systemic risk, and therefore minimize the risk of a taxpayer-funded bailout.

You can’t have ample liquidity at all times and not be propping up systemically important institutions when they get in trouble.

Treasury’s ideas for relief consisted of raising various bank size thresholds for compliance, giving “lenders” more trading latitude, and lifting the restrictions on how much capital banks can invest in their own private equity and hedge funds. Let us stress that there is no social purpose whatsoever for this activity. There is no shortage of asset managers. This is a pure gimmie. But the Treasury document goes on at some length to argue that banks need relief on “covered fund” rules so that they can set up more venture capital funds. VC funds back a whopping 1% of startups and on average perform even worse than private equity as a whole (the entire industry performance is due to the outliers at the high end).

On top of that, as Bloomberg stresses, it will be harder to get regulatory reforms than you’d think, particularly on the Volcker Rule:

It is not clear how quickly regulators can act on many of the recommendations in the Treasury’s 150-page report.

Key positions at the Federal Reserve, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. are either unfilled or held by Obama appointees. Also, the byzantine process for approving regulations doesn’t lend itself to quick fixes. Rules must be written, offered for public comment for several months and then deliberated internally before a final vote…

Some of the most unpopular regulations that the report asks to re-do, such as the Volcker Rule ban on banks’ proprietary trading, were put together by five different agencies. Each one would need to sign off on revisions following those onerous steps.

The Wall Street Journal echoed those issues:

The report marks the beginning of what will likely be a yearslong review of financial rules.

Some recommendations, including exempting small banks from the Volcker rule, limiting the consumer bureau’s authority, or expanding FSOC authority, would require congressional action—a potentiallyhigh bar amid deep partisan tensions on Capitol Hill.

Other changes would need regulatory approval from officials who might not be in place for months. Many bank rules must be approved by the boards of the Fed and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., but the leaders of those agencies have terms that haven’t expired yet. Mr. Trump also hasn’t nominated anyone to a number of significant regulatory roles, including the top bank oversight post at the Fed.

A senior Treasury official said most of the report’s recommendations could be carried out by regulators without help from Congress. The only current bank regulator appointed by the new administration, acting Comptroller of the Currency Keith Noreika, said Monday the report will inform his agency’s work aimed at reducing regulatory burdens at the federally chartered banks it oversees.

Another big hot button for the banks is the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. With class action lawsuits, which historically had been the big check on bank grifting, largely neutered, the CFPB showed it could stop that sort of thing through its role in the Wells Fargo fake accounts case. Admittedly that came about a bit by accident; it was the Los Angeles Times and then the Los Angeles City Prosecutor, using the CFPB complaint database, that did much of the critical early spadework. And in fairness, regulators aren’t set up to go after bank frauds that are designed to rip off customers by small amounts unless they can find evidence in computer programs or other documents that provide a paper trail showing that it was institutionalized. Creating a culture where managers marched to largely the set of orders in absence of formal documentation made it particularly hard for any regulator to ferret out what was happening until the noise from customers got loud.

But the bigger point is the CFPB got lucky. The way the Wells Fargo scandal exploded into a big national story means bank whinging about the CFPB looks highly suspect. So Treasury isn’t backing House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling’s scorched earth approach. However, one of the changes Treasury is pumping for, that of making the CFPB’s budget subject to Congressional approval, will be enough to render the agency toothless. Other major bank regulators are self-sufficient, making do off their fees and fines. By contrast, the CFTC, which is generally seen a secondary regulator, and the SEC are kept on a short leash by Congress through the budget process. The SEC, which was a feared and respected agency when I was a kid on Wall Street, has become a joke as a result. For instance, Arthur Levitt, the SEC chairman under Clinton, recounted how he was regularly threatened by the Senator from Hedgistan, Joe Lieberman, for any weak efforts to protect retail customers.

I know I should probably debunk some of the many canards in the Treasury document but every page is thick with them, and even going after one takes about three times as many words as it does to purvey the bogus spin. For instance, one canard is blaming less mortgage lending and in particular, the dependence of the mortgage market on government guaranteed loans, on those nasty post crisis regulations.

First, before the crisis, about 40% of the mortgage originations were subprime. And 75% of those were securitized, so banks didn’t keep them.

The reasons that market hasn’t come back is due to the lack of regulations. This is one of those few cases where investors were so badly burned that they were leery of getting back in the pool in any serious way for years.

Back in 2010, he FDIC proposed four changes to subprime origination needed to satisfy investors. The securitization industry refused to support them. That was far and away the biggest constraint on mortgage lending in the years after the crisis.

The new rules do require borrowers to submit more paperwork. I find the complaints remarkable given the sort of documentation I had to provide when getting mortgages in the 1980s. And why is it airbrushed out of collective memory that as early as 2006, the FBI estimated that up to 70% of early payment defaults were due to misrepresentations on loan documents? More stringent documentation makes that a lot harder. Behavioral psychologists also pointed out that the ease of getting mortgages, and supposedly expert banks’ eagerness to tell borrowers they could afford even bigger houses helped induce borrowers to get in over their heads (I didn’t take cabs all that often in 2007 and 2008, but when I did, especially outside NYC, I frequently had the driver volunteer that a banker tried to get him to buy a bigger house than he knew he could afford).

Lenders were also more stringent about borrower FICO scores even for prime (Fannie/Freddie) mortgages. But the big cause was not all that supposedly pesky Dodd Frank paperwork. Georgetown law professor Adam Levitin debunked that yesterday for us, summarizing his Congressional testimony:

Some of the stuff the small banks are whining about doesn’t hold up. For example, they’re very upset about the additional 24 data fields they have to collect under the CFPB’s new HMDA rule. That sounds like a lot until you look at the fields required and realize that all but one of them are already being collected either for underwriting purposes (e.g., the street address of the collateral property) or for the TRID (e.g., the broker’s NMLSR number) or both. The sole exception is the borrower’s age, which would be collected for a reverse mortgage underwriting, in any case. It should take a lender all of perhaps 5-7 minutes per loan to collect and enter the data into a computer program. The CFPB thinks the compliance burden will translate into 143-173 hours of additional time per small institution. How this is a major compliance burden absolutely baffles me. And no one bothers to mention that the new rule exempts 1400 institutions (mainly small banks) that currently report data and covers some 450 that don’t (primarily nonbank). Put another way, the discussion has almost nothing to do with facts.

So if it wasn’t Dodd Frank, what was led the banks to focus so much on high FICO score borrowers? It was mortgage servicing reforms, which made it hard to foreclose due to stopping abuses, like dual tracking (continuing to foreclose even when supposedly considering a mortgage modification).

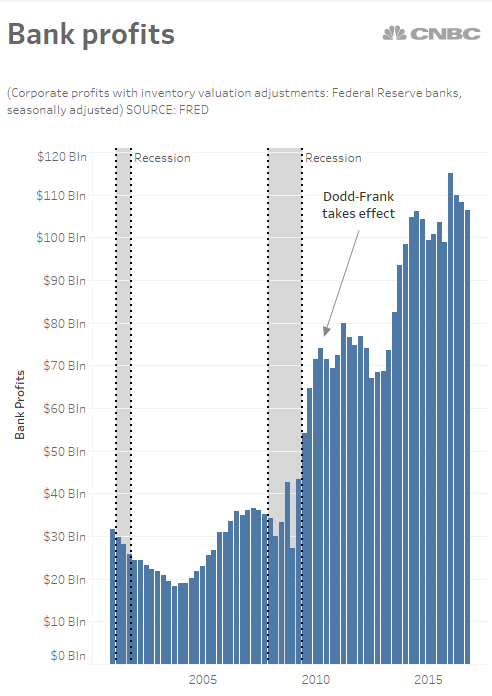

To look at the bigger picture, it’s hard to take bank complaints about oppressive regulation seriously in light of this:

And if you had any more doubts, reader JGK gave some additional color in comments:

As a former DC lobbyist for a credit union trade association, I can verify that all the trades are getting behind Dodd-Frank repeal, even if it only marginally benefits their members. At this point, these decisions are far more political than practical. They went to get in good with the Republican majority and punch back at CFPB for keeping them accountable. And the compliance costs at this point are baked in. Just about all of the regulations emanating from DF are fully in effect and the compliance costs have already been imposed. Repealing these regulations wont save any money for institutions, since all their compliance systems are already in place. In fact, repealing regulations that are already in effect can actually cost banks, since they need to go back and make changes again.

As for the exam threshold, the big banks have more than enough resources to deal with an additional CFPB exam, especially given that the prudential regulators are focused on a million other issues, least of which is the growing concern over cybersecurity and credit card hacks.

Consistent with what Levitin said yesterday, the small bank campaign against Dodd Frank isn’t about their economics. It’s largely ideology. It’s one thing to have a Republican Administration spinning otherwise. But shame on the press, which ought to have figured that out by now.

That picture of bank profits graph really is worth a thousand words. Thank you for posting.

Welshes? What do the people of Wales have to do with this? Do you mean something or someone other than the Welsh?

I suggest you acquaint yourself with a dictionary.

When I was a child, I thought the slang word for “renege” was “welch” (of course I did not know the word “renege” when I was a child). I also thought that the slang for “cheat” was “jip”, but it’s actually “gyp”, as in “Gypsy”. I did know the correct spelling of “Dutch treat”.

One of the other reasons I like NakedCapitalism, I often end up looking up the etymology of various words that pop up here (I always spelled it welch/welched)

https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/72806/are-the-terms-welsh-or-welch-as-in-reneging-on-a-bet-derogatory-toward-the

Per Wikipedia, “….that etymology remains conjectural.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welsh_(surname)

This legislation isn’t about what’s good for small business or for the banks or bank holding companies in terms of fulfilling their public purpose. Instead, it’s about regaining control of the banks and banking system so some individuals can engage in speculations, predatory lending, and other activities to game the system for private gain at public expense without fear of being exposed to individual civil damages or criminal prosecution.

It has been clear for years that we need legislation to restore the Glass-Steagall Act, and criminal prosecutions of criminal acts, instead of this blatant effort by a relative few to enable reformation of an environmental petrie dish that fosters such deeply damaging business cultures and individual behavior at such great social cost, and leads to concentration of great wealth in few hands. Those who presently control the banks, their lobbyists, and the legislators who are pushing this legislation are willfully ignoring the social environment in which they now operate and should be replaced IMO.

I saw in California many loan modifications such that the new mortgage account balances were $20k+ over the original loan amount balances of the modified interest bearing mortgage accounts. Four or five unpaid monthly installments very much equaled all past due interest. So the new loan would refinance all that interest plus all accumulated late fees. In other words, interest charged on interest charges and interest charged on fees which previously were not accruing interest. It puzzles me not to recall anyone advocating for treating the original over due loan interest and late fees as add ons not subject to interest charges.

I read Adam Levitin’s article on servicing. I agree with him, although there is one thing no one says and just about everyone knows: good customer service is very expensive. Knowledgeable employees are required to provide caring customer service, which can imply higher salaries and too much time spent on tasks which do not make the enterprise earn any money. The progressive reaffirmation of the separation between residential mortgage lending and servicing is true to this. Once the lender at lightning speed receives the deposit from the dealer and sends it to the seller’s bank, financial engineering and marketing securitization are paramount: this is where the money is and where the the money lover has to be. Servicing is too costly; must outsource it overseas and automatize it! This is why mortgage servicing companies do not have any tools to diagnose and deal with solvable transient delinquency anymore (even hard money lenders used to have tools at their disposal before). This is why borrowers receive aggressive letters stating their homeowners’ insurance does not include sufficient coverage (when there is actually plenty of coverage amount, but the employees overseas do not know how to read an insurance policy). This is why every two or three years the borrower’s second mortgage servicing is transferred form one company to another one and the latter forces impound HO ins accounts when the primary lienholder already has an escrow & insurance account, etc.

This isn’t quite correct.

Routine mortgage servicing is cheap and highly automated and routinized. It’s just booking mortgages, collecting and payments, remitting information to the securities agent servicing the mortgage securitization (I forget the term of art), and taking the mortgage off the books and determining where the proceeds go in the event of a refi or sale of the home.

Default servicing, done properly, is not.

And servicing is still done largely domestically. The overwhelming majority of banks, particularly the big ones, do it in house. I’ve been at conferences for the securitization industry for years. All the mortgage abuses were reported by low level insiders working for servicers. The OCC Independent Mortgage Review details were of domestic concerns. Even the default servicers are domestic.

And no, mortgages are warehoused for as much as six months before they go in a securitization. They are often traded between banks.

An increasing trend. For example Citigroup-this, at least at first, will be domestic but not in house anymore:

http://www.stltoday.com/business/local/citigroup-to-exit-u-s-mortgage-servicing-operations-by/article_8150913e-3a12-5e98-87e2-49107f4c6fdc.html

Outsourcing to India, this is from 2013 and it is a low volume by industry standards. However if my recollection is correct volume growth has increased since

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324059704578474470798073356

When I said paramount, I did not mean quickly. (my reference to lightning referred to funding through i.e CHIPS ,and I said it for effect, just disregard that not pertinent part )

It seems to me that routinization can exclude good customer service. When the employee cannot tell the difference between first and second lienholder or does not understand what an insurance policy guaranteed coverage is, dealing with customer service can turn into a part-time job. How often do we call a service provider and the automated phone system and the routinized script do not meet our concerns?

Additionally for subprime mortgages proper early default treatment had always been intertwined with customer service and certain human discretion authority for many years . The automatization and routinization you are alluding to have contributed to that treatment’s disappearance.