As the credit crisis progresses, the estimates of the total damage march relentless upward.

Reader Scott passed along a note by Frank Veneroso, Market Strategist for the Global Policy Committee of Allianz Dresdner Asset Management, which gives a top-down and bottoms-up estimate of credit losses. Note that this estimate is based strictly on US consumer and commercial borrowing. It does not allow for knock-on effects, such as counterparty defaults in the credit default swaps market.

The letter is too long to post in its entirety. It does a nice job of summarizing the history of overleverage in the US, Great Depression to present, emphasizing the unravelling of the penultimate credit boom (the late 1980s) and how our current situation compares (short answer: a lot worse).

Veneroso stresses that the makes relatively conservative assumptions, for instance, that housing prices do not revert to the mean; the economy does not fall into a recession. Given that past housing busts have featured prices dropping below the historical averages, these assumptions are if anything generous. Yet he comes up with total losses more than double the most dire official estimate so far, the recently-published IMF figure of $945 billion.

Veneroso’s projections can be characterized as back of the envelope, but given how far we are outside historical norms, anything more formal might convey an illusory sense of accuracy.

From Veneroso:

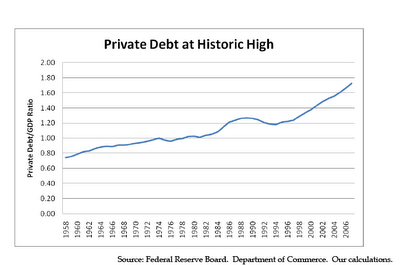

In what follows I try to come up with such an estimate…The top down approach looks at the ratio of private debt to GDP. It compares the 1989-1992 episode to the current episode to come up with a top down estimate of excess debt prone to default and likely default losses.

The bottom up approach looks at each class of private loans that everyone agrees are prone to defaults and losses.

Both the top down and the bottom up approach tend to agree: total credit losses in this cycle under sustained current conditions will be two times the recent estimate of the IMF. As the IMF is a conservative bureaucracy and has been behind the curve, such an estimate should not seem wild-eyed.

The above analysis assumes further declines in U.S. house prices but not a 35% decline to the mean. It assumes a wobbly economy for several quarters but not a full blown recession. I believe mean reversion in home prices and a full blown recession are highly probable. Under such conditions aggregate defaults and credit losses would be significantly higher…..

My assessment is that we currently have a solvency problem on a huge scale and that the prevailing systemic illiquidity is a response to the recognition of such a large scale solvency problem by all classes of economic agents…. Furthermore, so far I am discussing dead weight losses on the credit instruments that underlie structured products. There are several overlying derivative structures. I believe that there may be further large scale losses that may beset core institutions above and beyond the dead weight losses on the underlying that credit default will bring….

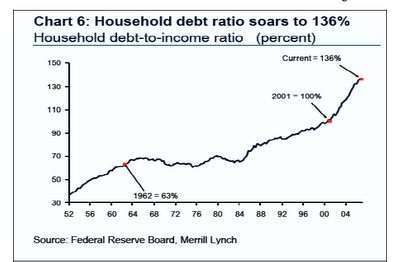

One macro assessment can be gained by looking at the level of aggregate private debt to gross domestic product (which is a proxy for private income). Below are two charts. One presents the ratio of all private debts –both household and corporate – to GDP; the other focuses only on the household debt to GDP ratio.

….it is possible to say that much of the increase in the ratio of household debt to GDP from 100% in 2000 to 137% in 2007 occurred only because loans were being made to people who could not pay on a massive scale. Household loans equal to perhaps 20% or 40% of GDP were excess private debt by 2007. This is a debt excess of the household sector that, relative to GDP, could be 5 or 8 more times that of the period 1989-1992,even after making some allowance for rising sound private indebtedness resulting from greater affordability of lower nominal interest rates and the increase in penetration of financial intermediation.

So far I have focused on the household sector. The ratio of corporate debt to GDP regained its 1989 peak level by 2000. Another wave of corporate credit difficulties then ensued. In this cycle it is widely believed that there has been a reduction in the ratio corporate debt to GDP. In fact the flow of funds data shows that this ratio was as high in 2007 as it was at its prior cycle peak…. However, it is a fact that the lowest grade corporate debt – junk bonds and leveraged loans – have doubled in nominal terms in this cycle when nominal GDP only rose by 35%. So it would appear that there might be a much greater excess of corporate debt relative to income in this cycle relative to both the late 1980’s and late 1990’s cycle peaks….

If the total aggregate of such excess private debt is more than 30% of GDP, we are talking about more than $4 trillion in defaulted loans. As recoveries tend to average 40%, we are talking about $2.5 trillion in dead weight credit losses by all classes of holders of such credit instruments over perhaps a several year period of “workout”.

Okay, okay. That sounds too large. So let us say the debt excess is only 20% of GDP. That implies defaults on almost $3 trillion of loans and dead weight credit losses of almost $1.8 trillion. The IMF just estimated such credit losses will be almost $1 trillion over this episode. I would put the eventual total at twice that given my macro financial perspective.

Could the problem really be that bad? I believe if we look at various components of the private debt superstructure of the U.S. economy we will see that it can easily be that bad…

Subprime Mortgages

….There is an alarming rise in delinquencies and defaults on subprime loans, including loans which were very recently made and have had little time to season into sour loans. Recent data suggests that delinquencies on Alt A and Alt B loans are running at 70% of those on subprime….It is estimated that there are outstanding a total of $2.5 trillion of subprime, Alt A and Alt B residential mortgage loans combined.

Second And Third Household Mortgages

Being junior claims piggybacking first mortgages, seconds and thirds must surely be prone to default. Because many seconds and thirds are granted outside traditional channels their outstanding volume is probably greater than most estimates. Dismal seconds and thirds may approximate one half a trillion dollars.

Home Equity Loans

Home equity loans are basically a short to medium term second mortgage loan. They tend to be loans to households with financial deficits and an overall very high loan to value ratio. In the current environment they would appear to be highly prone to delinquency and default. And in fact default rates are rising rapidly. There are a half a trillion dollars of home equity loans on the books of banks. A substantial amount of home equity loans have been securitized. Total home equity loans outstanding probably approach $1 trillion.

Consumer Loans

There are approximately $1 trillion of consumer borrowings other than mortgages and home equity loans outstanding. In the past payment rates were high but, by the 4th quarter of last year, delinquencies rose in percentage terms to 1992 levels….

Prime Mortgages

There are almost $8 trillion in prime mortgages. Until fairly recently most analysts thought that this class of mortgage loans would not be prone to delinquencies and defaults. But half of the GSE foreclosures so far in this cycle involve prime mortgages…. Fed Governor Janet L. Yellen noted that in this cycle mortgage defaults appear to be a function more of house price declines than anything else… This of course opens Pandora’s Box. We have no idea what percent of the almost $8 trillion prime mortgages may be default prone in this cycle. And even if the percent is low, the default prone aggregate involved may be in the many, many hundreds of billions of dollars.

So let’s add up all the classes of default prone household borrowings. The total is on the order of $6 or $7 billion overall. Of course only a portion of these loans are likely to default. But it would appear, especially in an environment of declining house prices, that excess household debt that is default prone is on the order of several trillions of dollars or more.

What about business as opposed to household debts? As I said above many believe there has been balance sheet repair in the U.S. but the fact of the matter is that the corporate debt to GDP ratio is back to the 2000 cycle peak. Furthermore, the corporate sector is now running a financial deficit equal to that of the prior 2002 cycle peak…

What is the aggregate U.S. business loan loss exposure? ….

First commercial mortgages on Ponzi terms. Nouriel Roubini’s group estimates this debt aggregate at $900 billion, with an expected default experience of $150-$200 billion and ultimate losses of $90 billion. Is this estimate valid? It seems plausible to me and I haven’t found a better analysis.On to junk bonds and leveraged loans. There are $3 trillion outstanding. Because of the explosion in Ponzi securitization in 2006 and early 2007 corporations that would normally have been unable to service their debt refinanced on liberal terms. Consequently, default rates, typically 3% to 4% in a normal year, fell to less than 1%. Now the Ponzi refinance option is gone. In time debts will come due again and default rates will rise.

Both S&P and Edward Altman have forecast a default rate this year of 4%-5% amid slow growth that falls short of recession. This seems reasonable given past default experience and the current overall environment. That translates into defaults of almost $150 billion and losses of almost $90 billion.

Top Down And Bottoms Up Approaches: Conclusion

Let us assume very slow growth and a benign fed funds and treasury interest rate environment as well as the current financial crisis. That implies possibly zero economic growth but no significant recession, an “easy” monetary policy, and tighter credit standards. What kind of defaults and dead weight losses do we come up with?

On the household side it is hard to say, largely because of uncertainty as to how affected will be prime mortgages and consumer debts. But defaults of $3 trillion out of a default prone aggregate of $7 trillion seems realistic to me. That brings with it $1.8 trillion in dead weight losses. To this we might add almost $300 billion plus or so of business defaults and more than $150 billion of dead weight credit losses over time. The business losses bring the total into the $2 trillion range.

No big deal really, as The Fed is backing up stocks, which act as collateral for all the bad synthetic bets; relax, Ben has more money and stocks are on fire and the next bubble is under way, which covers the other bubble. No worries!

Shughart on Bailouts

Don Boudreaux

http://cafehayek.typepad.com/hayek/

The record of government bailouts of private financial institutions in the 1930s, of Continental Illinois Bank in 1984 (which cost $8 billion) and of the entire U.S. savings & loan industry in the late 1980s and early 1990s (which cost $125 billion) teaches that emergency loans keep weak institutions alive just long enough for their problems to increase. Bailouts encourage more risk-taking and eliminate the freedom to fail that is just as essential to a free-market economy as the freedom to succeed.

I am an uber bear, but I do not buy the analysis. 50% of default prone loans will not go into default. We may well hit $2T loss – but only if house values fall enough to send a substantial sum of prime borrowers underwater. Even then we are in uncharted territory.

“So let’s add up all the classes of default prone household borrowings. The total is on the order of $6 or $7 billion overall. “

Trillion?

Winslow R.

Anon of 1:39 AM,

I should have mentioned in the set-up that he seemed to be putting an awfully large percentage of prime loans in the default prone category.

I should have mentioned in the set-up that he seemed to be putting an awfully large percentage of prime loans in the default prone category.

More pessimism about prime loans may be justified (although maybe not quite so much of it) because at this point it has been consistently shown that negative equity is the biggest factor in defaults, and not ability to pay (i.e. the ‘primeness’ of the loan). And whether a borrower falls into that has little to do with his own personal situation. Factor in (likely) increased joblessness going forward.