On the one hand, I should be flattered that Brad DeLong took the time and trouble to take two posts (here and here) to respond to my comments on an earlier post of his, in which I objected to his and Summers’ notion of having the government fund either directly or indirectly, the purchase of mortgages. On the other, as I will discuss below, he objects to my argument by invoking theory, which was (although I did not make that explicit) one of the reasons I took issue with his original post, namely a lack of reference to facts on the ground in the housing market. I’ll admit I didn’t invoke data in that particular post because it was getting long and I’ve covered that ground extensively elsewhere, but that might have misdirected him.

He mentions in his current post that he and Summers also advocated the recapitalization of banks; note I did not object to that (although I am not keen about government funded recapitalization unless the industry also put on a very short leash, I view that as a more efficient and therefore lower cost way to salvage the financial services industry than propping up either the mortgage or housing markets. Those I see as inefficient and therefore more costly, but more in the short term more politically palatable ways to address the same end because the costs are largely invisible to the great unwashed public, at least till the losses and dislocations come home to roost).

Let me give you the guts of DeLong’s riposte:

That’s Smith’s argument: that Larry Summers and I neglect the implications of the fact that “the government cannot keep asset prices from declining to their fundamental value.” How sound is it?

The fundamental value of any risky asset–housing, say–depends on (a) per-period value or profit, (b) the time profile of safe interest rates, (c) the quantity of risky assets that the private financial sector must bear, (d) the amount of risk associated with each tranche of risky assets, and (e) the risk-bearing capacity of the private market. All of things are things that can be high or low–and that the government can affect:

A competent government that keeps the economy near full employment boosts future profits and values; an incompetent government that fails to stem an economic collapse into depression diminishes them.

Similarly, a competent government that keeps asset prices from being pushed into fire-sale territory by irrational pessimistic panic diminishes the amount of risk associated with each tranche of risky assets.

The Federal Reserve controls the time profile of safe interest rates. No argument.

The government can buy up or guarantee risky assets, thus diminishing the quantity that the private market must hold–unless you adopt some hyper-Barrovian pose and are willing to maintain that Bernanke-Paulson puts are not net wealth.

The risk-bearing capacity of the private market can be extended via financial regulation that diminishes the chance that a relatively uninformed investor is being victimized by someone with inside information, and widens the pool of investors willing to bear risk.

What, then, is this “fundamental value” to which asset prices must decline if government policy can have effects–profound effects on nearly each of the factors on which fundamental value depends?

The Marx-Engels-Hayek-Smith line of argument does attempt a parry. It says that the root problem is overproduction–that we have too many houses. Attempts to change fundamentals will mean that those who build more houses will continue to earn more profits, and so we will have more and more and more houses, and we will have an even greater overproduction crisis some time in the future. So we must make sure that housing prices are so low that nobody builds another house for a long time to come, and that is the only way to minimize the misery coming out of the collapse of the housing bubble.

I have never been able to make this “overproduction” argument make sense. If the government provides a subsidy–like a mortgage insurance subsidy–then we will indeed have more of whatever the government subsidizes, but there is no reason to think that this is in any way a big problem or an unsustainable situation. It may well be a waste of the government’s money to provide the subsidy: taxpayers might rather endure a housing crash and a depression than be forking out extra taxes to pay mortgage guarantees. That’s an empirical and a cost-benefit issue.

If I read DeLong’s argument correctly (and readers are invited to disagree), he rejects the idea that there can be such things as asset bubble because they are based on an idea promulgated by economists not held in much esteem these days (Marx-Engels-Hayek) of overproduction.

In fact, there are other constructs for this precisely this sort of bubble made by economists held in higher repute. Consider the abstract of George Akerlof’s and Paul Romer’s “Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit“:

During the 1980s, a number of unusual financial crises occurred. In Chile, for example, the financial sector collapsed, leaving the government with responsibility for extensive foreign debts. In the United States, large numbers of government-insured savings and loans became insolvent – and the government picked up the tab. In Dallas, Texas, real estate prices and construction continued to boom even after vacancies had skyrocketed, and the suffered a dramatic collapse. Also in the United States, the junk bond market, which fueled the takeover wave, had a similar boom and bust.

In this paper, we use simple theory and direct evidence to highlight a common thread that runs through these four episodes. The theory suggests that this common thread may be relevant to other cases in which countries took on excessive foreign debt, governments had to bail out insolvent financial institutions, real estate prices increased dramatically and then fell, or new financial markets experienced a boom and bust. We describe the evidence, however, only for the cases of financial crisis in Chile, the thrift crisis in the United States, Dallas real estate and thrifts, and junk bonds.

Our theoretical analysis shows that an economic underground can come to life if firms have an incentive to go broke for profit at society’s expense (to loot) instead of to go for broke (to gamble on success). Bankruptcy for profit will occur if poor accounting, lax regulation, or low penalties for abuse give owners an incentive to pay themselves more than their firms are worth and then default on their debt obligations.

Similarly, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff have circulated an elegant and rather disconcerting paper, “Is the 2007 U.S. Sub-Prime Financial Crisis So Different? An International Historical Comparison” From their paper:

The first major financial crisis of the 21st century involves esoteric instruments, unaware regulators, and skittish investors. It also follows a well-trodden path laid down by centuries of financial folly. Is the “special” problem of sub-prime mortgages this time really different?

Our examination of the longer historical record, which is part of a larger effort on currency and debt crises, finds stunning qualitative and quantitative parallels across a number of standard financial crisis indicators.

I could provide other support, but I figured I’d limit myself to some contemporary economists held in high esteem. Yet De Long chooses to assert that the only basis for my argument is “Marx-Engels-Hayek” which has the interesting effect of putting me in the same camp as admittedly famous names who are seen in most quarters as outdated and/or cranks who might have had an occasional valid observation.

De Long also quotes Keynes in a manner that suggests that I am on the side of cold water Yankees who want to punish speculators and that does a disservice to the economy as a whole. I hope some readers will go through the DeLong post and do a sanity check on whether I am being unduly sensitive, but I read a veiled ad hominem attack in how he constructs his argument and cites Keynes to misconstrue my point.

As an aside, I must also note that DeLong did not indicate the date of Keynes quote, which also says that the “world was enormously enriched by the constructions of the quinquennium from 1925 to 1929.” That may well be true; that period (in terms of innovation) may have had more in common with out dot-com era. But I find it hard to see how the world, or even America, was enriched by five years of housing (and to a lesser extent, commercial real estate) speculation, particularly now that we are going into a period of energy scarcity. Costly-to-heat McMansions will be as fashionable and useful as bell-bottoms. Similarly, the Dow did not return to its 1929 peak till 1954. A generation of wealth was destroyed to pay for those enormously enriching constructions of 1925-1929, and enthusiasm towards stocks did not return till the 1960s. I wonder if Keynes would have toned down his positive words for the 1925-29 period had he had a full view of the costs.

DeLong, in essence, argues that there is no such a thing as fundamental value because government can influence a lot of the variables that determine value. Yes and no.

One of the things that I have done frequently over my career is value financial assets, often in markets where it is very difficult to find benchmarks or regulatory or technological change makes valuation a tricky task. And as most investors know, market prices can trade away from fundamental values for a very long time (currencies are particularly noted for this behavior). As Keynes said, “The market can stay irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

Nevertheless, there are several important points DeLong misses:

1. The Fed’s influence over interest rates is limited. It can only play with the short end of the yield curve. For instance, even though it would have liked to bring down long rates as well as short rates, inflation fears have led to some particularly weak ten-year auctions, and fixed mortgages key off longer-dated Treasuries.

2. The government’s ability to take effective action to shift prices in a market as large in the housing market is limited; we are already seeing policy measures unintended consequences that come close to negating the benefit of the initial measure.

Housing is a $20 trillion market. Mortgages are estimated to have a face value in the $11 to $12 trillion range. Paul Krugman compared the Fed’s efforts with the TAF and other moves to increase liquidity to currency intervention and drew some of his cartoons to illustrate. But he noted that the Fed’s influence is limited:

OK, this is just like the way you analyze sterilized intervention in currencies. And the usual problem with such intervention applies: the financial markets are so huge that even big interventions tend to look like a drop in the bucket. If foreign exchange intervention works, it’s usually because of the “slap in the face” effect: the markets are getting hysterical, and intervention gives them a chance to come to their senses.

And the problem now becomes obvious. This is now the third time Ben & co. have tried slapping the market in the face — and panic keeps coming back. So maybe the markets aren’t hysterical — maybe they’re just facing reality. And in that case the markets don’t need a slap in the face, they need more fundamental treatment — and maybe triage.

This means that to move mortgage prices, the federal government would have to become a big enough buyer to have a price impact. I have no idea how big that number is, but given that other measures have failed, it will be very large. And these large scale efforts to shore up the housing market have either been ineffective or have backfired, as we detailed in an earlier post. Similarly, John Dizard pointed out that expanding the role of Fannie and Freddie, every politician’s favorite solution to the problem, is likely to create systemic risk:

This process of risk control on the part of the GSEs creates systemic risk for the fixed-income markets. GSE hedging tends to be pro-cyclical….. So the hedging activities tend to accentuate market moves. As rates rise and bond prices fall the GSEs are, in effect, selling fixed-income derivatives into a falling market. As long as the derivatives books are small relative to the size of the market, that is not a big problem. When the GSE derivatives books got big, that was a problem.

By 2001 Fannie and Freddie together had more than 10 per cent of the total market in dollar-based interest rate derivatives. That concentration of risk was worrisome for the central banks. As we wrote at the time, they were concerned that the banks and brokers who were the counterparties for the GSEs would need back-up for these commitments from the Federal Reserve Board. Worse, from the point of view of the Fed, and Alan Greenspan in particular, the GSEs’ management had financial incentives to continue to expand their books of business….

Then Mr Greenspan, the GSE regulators and their geeky allies got lucky. A management compensation scandal broke at the GSEs ….

Unfortunately, the squeezed balloon of mortgage credit just bulged out elsewhere. The GSEs, and the rest of the financial markets, assumed more credit risk, and they are now incurring those very real losses….

If this balance sheet growth does happen, the GSEs will be back to assuming the same rate risks that were so alarming four or five years ago, only bigger. And they will be attempting to hedge their rate risks using counterparties that are far more capital constrained than before.

Another constraint on the Federal government’s ability to act is our massive current account deficit. Japan is the only precedent I can think of for an asset-propping exercise of this scale, and most do not deem it to have been a very successful experiment. And Japan at least had the advantage of a very high domestic savings rate and thus could manage its crisis internally. Brad Setser has already found ample signs that private capital flows are drying up and we are largely dependent on foreign central banks. Dizard indicates in a current article in the FT that the Fed is unwilling to balloon its balance sheet to provide lending facilities for banks (it has maybe $300 billion of capacity left before it would have to issue more liabilities).

3. Subsidies and interventions to prop up the housing market, which does nothing for the competitiveness of the US economy, will divert capital from other uses. Note that the US already has one of the most heavily subsidized housing markets in the world, between the mortgage interest deduction, FHA, and Fannie and Freddie.

4. DeLong views the current situation as “irrational pessimistic panic.” I’d say what we are having instead is a rude awakening that trees do not grow to the sky. He was not evidently not following the markets closely in 2006 and 2007, when signs of irresponsible lending were rampant and you saw bubble-like growth in almost every asset class except the US and Zimbabwe dollar (oh, and the yen, the foundation of the carry trade which helped turbo-charge this situation). Has DeLong considered the nasty problem of counterparty risk in the credit default swaps market? Many people believe that was the main reason for the Bear bailout, that Bear as a CDS protection writer could not be permitted to default (or have uncertainty about the value of its contracts) for it would precipitate a massive unwind in the CDS market. That is a train wreck waiting to happen. The damage to the large financial firms that have become central to credit intermediation could be as bad as that caused by the mortgage market meltdown. As I said above, these markets are too big for the government to rescue, and it is wasting valuable firepower trying to do so.

A colleague who has security clearances and close contacts at the Treasury and Fed (yes, I know some people on the dark side) said some months ago that the Fed and Treasury were looking into a partial nationalization of the banking system. This is from an Administration that is ideologically opposed to that sort of measure. That (and the blunt comments of the Japanese that we need a government bailout of our banks, which is completely out of character for them). This is not irrational panic.

Let’s get away from abstractions.The old fashioned way to value financial assets is via discounted cash flows (and yes, this is problematic because you have implicit assumptions about reinvestment rates, you need to choose a discount rate, and most models use a terminal value computation which inevitably swamps everything in the calculation. Comparables is another popular method, although that has the convenient effect of muddying the question of price with value.; it’s what real estate appraisers and those who value non-income generating assets, such as fine art, use).

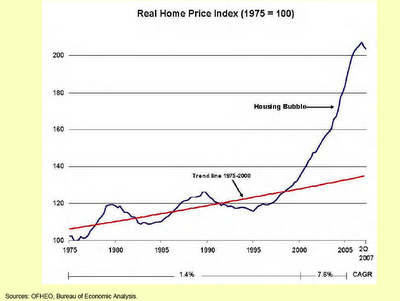

Housing is priced in relation to prevailing income and rentals. There is ample evidence that housing is now (still) considerably overpriced in relation to incomes (click to enlarge):

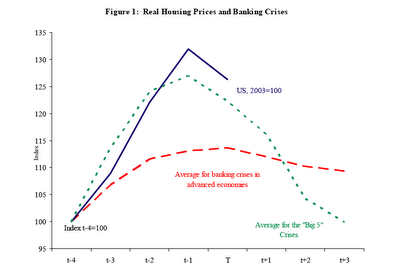

This chart from the Reinhart/Rogoff paper suggests the trajectory our housing prices are likely to follow. Note that in the “Big Five” which they felt was the most germane comparison for the US credit contraction, real housing prices reverted to their pre-bubble level, which shows we have a long way to go:

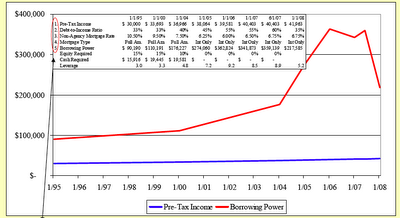

This chart illustrates how banks’ willingness to lend unprecedented amounts against income led to unsustainable increases in buying power:

And a final thought from Dean Baker, “Why Is Congress So Anxious to Make Homeownership Unaffordable?“:

That is a question that reporters might try asking proponents of Congressional plans to prop up housing prices in bubble inflated markets. There is no obvious public interest that i can see in sustaining above market house prices. The housing bubble has prevented millions of young families or people moving into places like New York, Boston, Los Angeles from being able to afford to buy a house or alternatively forced them to stretch their budgets hugely and take on dangerous debt levels.

It might be reasonable to think that Congress would want these prices to return to trend levels as soon as possible. Instead it seems determined to use taxpayer dollars to sustain inflated prices. Someone should as them why.

Go get ’em Yves.

I love it when, to reply to very clear points, DeLong returns to drawing squibbles on the blackboard, as if that somehow helps him.

IMHO Delong (and Summers et al.) are part of the reason for the mess that we are in, so of course they can’t recognize the intractability of the mess, because that would call into question their qualifications and good sense. At every hiccup in the economy, DeLong has been one to shout for lower interest rates, to keep consumption going. That this would have secondary effects – getting more and more people into more and more debt, creating an economy dependent on overconsumption – seems to have been lost on the dear professor.

We are in a mess and government action ain’t going to do nothing, ‘cept make it worse. Look at the Depression, where the Fed and economists all acted in the best of faith, and our conclusion today is that they just messed things up more. Same with Japan’s bubble economy. Sometimes it is just better to Do Nothing rather than Do Something. You wait until the dust has cleared and you have an idea of what needs to be done, and then you do it, rather than aiming high and low and firing at every sound in the forest. You might call this the New Deal approach – let the banks go bust, but at the end of the day provide government work and a minimal income so people can live.

Lucky you didn’t merely leave a comment on his blog – Prof. Delong has developed the habit of simply deleting posts containing any opinions or facts which don’t fit into his argument or worldview.

Which is generally the way of those that value theories over prosaic information. Especially information standing in stark contrast to what theory predicts.

Anon of 7:38: This is disturbing. While its obvious that Prof DeLong is hopelessly lost in a world of self-justifying theory (and, perhaps, a long term danger to any of his students who listen to him), I find it difficult to accept that he would be so closed minded and petty as to delete posts/comments that disagree with him. Is this really true?

DeLong has deleted comments of mine.

The one I remember best was when he got himself in a gander about some WashPo reporter saying something about executive options. The dear professor wanted to fire the WashPo writer when, in fact, it was the journalist who was right.

Yves,

Good stuff, but I wouldn’t bother lowering yourself to engaging with DeLong in his pig pen. The desperation and disingenuousness in his arguments is palpable (Yves & Dean: Marxist-Hayekians).

Anons, I don’t post in DeLong’s comments, but McArdle (FWIW) has also alleged that he deletes comments, so this isn’t the first time I’ve heard that.

Two parallel markets, speculative and nominal. The nominal demand curve exists, based on the factors relating to housing. The speculative demand is transitory and based on exhogenous factors. When the speculative demand is operative, a pricing wave appears, perhaps akin to PK’s high and low equilibrium price graph.

The exhogenous factors shift and the speculative demand vanishes, leaving only the nominal demand curve.

The policy prescriptions seem to be much more concerned with propping up the speculative demand curve than the nominal curve.

Thank you for your lucid explanation. I used to read Mr. DeLong but finally gave up when it appeared he had left the reality based community for good.

weinerdog43

DeLong has never understood the housing bubble at all–he posted years ago about how price didn’t matter, only the monthly payment. Well, it turns out that eventually the price does matter.

Anyway, DeLong actively deletes comments and has done so for a long time. My comments may not be brilliant, but they have not been deleted from any other blog. I bet he’ll be deleting quite a few this morning after he got hammered in his own comments section over his condescending response to your post.

If I recall correctly, some time ago around the heyday of the housing bubble, De Long had a post arguing that the prices of homes didn’t matter and that home buyers were instead interested in the carrying cost rather than the price. Having had considerable experience in RE development and finance I was somewhat shocked by this claim, not so much because no one in the business, from developers to end consumers thinks that way, but because someone did in fact think this, at least theoretically. It is not that people weren’t thinking about the price, au contraire, they were thinking about it a great deal, and in fact assuming that real estate prices only rise. One need not look far in the record to find widespread professions of this belief.

There is something much deeper at stake, I have come to realize, regarding certain thorny questions surrounding asset prices. One of the prevailing assumptions of many economists, call them post-Depression thinkers, is that assets are somehow a one way street, with temporary blips along the way, something you support on an endless march to prosperity, and that one facilitates this with cheap or free credit, almost unlimited in supply, and a continually debased currency (so-called “price stability”.) As one would expect great efforts are expended defending and constructing theoretical justifications for ignoring assets bubbles, supporting them if they are discovered, or maintaining their triviality or socioeconomic benefits if someone questions the dangers they pose. Anti-deflation orthodoxy, what I would argue is in fact the primary concern of dominant modern and contemporary monetary policy, dictates a bias for asset inflation because anti-deflation mechanisms are designed to minimize the danger that the currency will be treated as a store of value. The currency is supposed to be a high velocity and slightly unstable unit of exchange while assets serve as a surrogate for savings and stored value. This is the primary monetary mechanism of the American economy. The great fear, and it is a reasonable one, is that people will lose confidence in the value of assets and the solvency of financial institutions. Such a development would provoke currency hording, the bane of any “price stability” regime. Once you understand this fundamental drive of monetary and economic orthodoxy, many seemingly unsound or questionable practices make perfect sense. Take Bear Stearns, Bear Stearns was not saved because of counterparty risk or threats to other investment banks per se. Bear Stearns was saved because its collapse would have dealt a serious blow to confidence in asset inflation and the financial institutions that mediate the wealth effect. This is why shareholders, bondholders and facilitators get a piece of monetary pie, not because they deserve it, not out of some crony corruption, but because confidence in financial mediation and asset values dictates such an outcome. A Bear Stearns bankruptcy would have been another step towards treating the unit of exchange as something that should be horded, and most likely personally horded rather than through the mediation of a financial institution. This will not be tolerated, and any and all countermeasures will be considered to prevent it because it threatens at the core level of the monetarily managed economy.

So in a sense, taking an orthodox economist to task for advocating bail-outs of financial institutions or asset price targeting is like criticizing a Christian for their belief in God. You’re not going to get very far, and you’re probably going to provoke a zealous response shrouded in a scholastic haze of theory. One should expect to branded, at best, a wayward follower of misguided but well-intentioned priests, or at worst an outright heretic or charlatan. Consider the triumvirate of company a compliment really, an acknowledgment that one is, after all, one of the faithful and clearly well intentioned, albeit misguided by a theoretical blip along the way.

Advocatus Diaboli

“Normally, the market sorts out which companies survive and which fail, and that is as it should be,” Bernanke said. “However, the issues raised here extended well beyond the fate of one company.”

Bernanke said the Fed was concerned that because the financial system is so interconnected, the sudden failure of Bear Stearns could have led to a “chaotic unwinding of positions” that could have shaken already fragile investor confidence and further undermined the economy.

A disorderly collapse could also have cast doubt on the financial positions of other firms that did business with Bear, he noted.

“Given the current exceptional pressures on the global economy and financial system, the damage caused by a default by Bear Stearns could have been severe and extremely difficult to contain,” Bernanke said.

http://www.reuters.com/article/bondsNews/idUSN0236699720080402

De Long would be all for government putting a value on all homes in the US, we are well on the way to socialism and serfdom and as highlighted by Mr. Bernanke government knows best.

I will vote for you over De Long any time. You have earned my respect through you blogging. Thanks and keep it up.

i can’t help but consider lines of thought such as these in a different light than prof. delong does:

If the government provides a subsidy–like a mortgage insurance subsidy–then we will indeed have more of whatever the government subsidizes, but there is no reason to think that this is in any way a big problem or an unsustainable situation.

in other words, asset deflations are broadly avoidable with proper public policy, and depressions are broadly the result of a terrible error of management.

one of the most consistent features of the modern period is the conceit of the current — a sort of background of antipathy for all that came before. it frequently presumes earlier incarnations of ourselves to have been some combination of stupid, uneducated and inexperienced. it isn’t difficult to imagine why the prejudice is popular.

but i think a more nuanced reading of history backs a different view — that eras are defined by philosophies and paradigms that are over time pushed, thanks to the positive reinforcement or earlier successes, to their breaking points and then beyond. the people operating within the paradigm are neither stupid nor uneducated nor inexperienced — but they are operating under a set of assumptions that have succeeded heretofore in accordance with the paradigm of the era, and (it is taken as self-evident) will continue to work as expected ad infinitum.

they ignore (or perhaps are really incapable of properly interpreting, given the deeply-reinforced prejudices of the paradigm) that every imperfect paradigm must eventually fail because the imbalances that are part of its maintenance are at least fractionally cumulative — and that the cumulative imbalance is ultimately unsustainable.

i have no idea if we’ve reached that point — the end of the keynesian economic paradigm, as it were, for lack of a better label.

but prof. delong would seem here to deny that there is a paradigm at all — that modern economics are not so much a set of temporarily-operable assumptions accruing imbalances that will ultimately undo the paradigm as simply Correct (capital C, to denote its holiness), subject only to the virtue of its high priests.

i would note that mainstream social thinkers in all previous periods believed exactly in the same manner of their contemporary paradigm. all considered it to be extremely sensible, generally invulnerable if properly managed, indeed the height of human achievement.

yet not one such paradigm has avoided its fate — not as the result of “errors” but in spite of actions taken by authorities in harmony with the assumptions of the paradigm. nor will this one avoid a similar fate, i think it’s safe to say — because, as ever, too few appreciate the complexity of social systems and their ability to defy and destroy our necessarily simplistic assumptions about it and render everything we now believe we know about it null. *there* is where the error lies, i suspect.

There are Marxists economists worth reading, so waving them off can itself be a dogma.

Try reading Robert Brenner’s (Historian at U. of CA at S.D.) ‘Boom and Bubble’. Well worth one’s time.

Once very broad question: does price determine economics, or are there a multitude of factors, including those outside the classical limitations of a departmentalized economic outlook, that determine prices? The economic discipline of those like DeLong have cornered themselves into a very small space, limiting and determining their views and analysis. Factors such as the political (and I mean more here than just legislative/policy formation), cultural expressions, class relations, etc., also need to be accounted for.

His argument runs to the core of what is wrong with the American Economy, the notion that you can harvest capital via zero economic value endeavors. This is the financials services business model in a nutshell so it is not so surprising he makes such an argument. Fundamental value is not stationary, but it is inextricably linked to relative value, a point you make very clear. The same wotrthless tripes were made about the tech bubble. It is reassuring to know markets are always able to be manipulated. Perhaps Delong should have just said that assets are now pricing nominally

As an aside, Bernanke just said on television that he will not allow prices to fall 10% a year circa the great depression. Can you say deflation.

First, I must say that after reading Prof DeLong’s blog for probably four years, I would say that he holds Marx and Hayek in high esteem. He may not agree with their conclusions, but he takes them as serious thinkers whose work should be read, understood, and considered. So I don’t think he was at all denigrating your argument. He certainly doesn’t consider them as cranks. See, eg, here:

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2008/03/afternoon-coffe.html

In fact, they are assigned reading for his grad students.

Further, I generally do not see him making ad hominem attacks. I do think that, given some of his previous posts, he believes that, on net, the costs from the financial crisis might be greater if we don’t bail the sector out than if we do. Further, he believes that people often examine this from a moral angle, decrying moral hazard for example, than a simple “what will hurt worse” calculation.

Here DeLong outlines his characterization of the three stages of a financial crisis:

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2008/03/morning-coffe-1.html

Given other posts on his blog, he believes we are currently in stage III:

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2008/02/dealing-with-th.html

If Yves Smith is read as claiming there is a fundamental asset price to which we must return, and that value is unchanged in the long term by government intervention, then claiming that is a Marx/Hayekian argument is a reasonable characterization. And Keynes did, indeed, write a counterargument. This doesn’t have anything to do w/ asset bubbles per se; it’s merely that government action can (via bearing risk, creating regulations to help investors better estimate risk born, manipulation of safe interest rates, etc) can manipulate the fundamental asset price, and this may be the appropriate thing to do in our current situation.

earl hathaway / nakedcapitalismbluejeans@earlh.com

-take my pants off to email

Just because the government can make houses super-expensive forever and ever doesn’t mean it should.

It is amazing, though, to watch the US taking the path of centrally-planned economies. This will insure global competitiveness and efficient allocation of resources, (snicker)…

If De Long deletes otherwise decent comments that go against his grain, that kind of makes him a big hypocrite, since his major gripe with the MSM (“Oh Why Don’t We Have a Better Press Corps”) is the suppression of facts regarding BushCo.

Regarding risks to Bear Stearn’s counterparties, Yves says “Many people believe that was the main reason for the Bear bailout, that Bear as a CDS protection writer could not be permitted to default (or have uncertainty about the value of its contracts) for it would precipitate a massive unwind in the CDS market.”

John Hussman claims counterparties would be protected in bankruptcy. But as pointed out in Morningstar’s mutual fund forum, Hussman is wrong. See here http://socialize.morningstar.com/NewSocialize/forums/thread/2503492 If Bear were bankruptcy Bear’s counterparties would face losses.

“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” –Yogi Berra

Who knew Yogi could be a sage of the financial markets too?

I would just add that I have had several comments deleted by Delong from his blog, especially regarding Noam Chomsky who he hates with an unreasoned passion. Delong is part of the US socio-political structure (advisor in the Clinton administration) so he just flips out whenever he hears Chomsky’s name.

Delong attacks Chomsky personally but did once try to attack him factually, but what he wrote was utter nonsense, so much so that even the Delong groupies were forced to admonish him very gently in the comments section.

Delong ignores everything that is critical of the “system”; his oft mentioned hi-brow reading list never ever contains a book such as “behind the scenes at the WTO” which blows the lid off the very notion of “fair trade”. He doesn’t want to know about any of this “dirty reality”.

So in summary, forget Delong he is just another shill for the establishment.

I have never met him but I dislike him rather a lot.

Regards

Steve

I don’t think you should take DeLong’s critique personally. I think he just has the academics’ habit of trying to win the argument rather than to find the best solution to the problem.

As all academics know, the best way to win an argument is to rephrase your opponent’s view in a way that weakens it and then knock down the flimsy edifice.

De Long is a nobody. Hayek was a Nobel Prize winner.

Hayek (and more importantly, Mises), recognized that money supply inflation leads to over investment in assets (the asset class that becomes inflated is dependent on a number of factors such as ease of investment and liquidity of the asset class). The over-investment proceeds to the point where people who made the investment almost all discover at the same time they have created a huge overabundance of the assets. They all run for the exits at the same time and this causes a massive asset deflation.

As far as I’m aware, the Austrian school is the only one which has had a credible explanation for the continual formation of asset bubbles and their collapse.

Instead of deriding Hayek (and other Austrians) as a kook, De Long would be well served to spend some time reading Human Action.

It might help prevent him from making ludicrous conclusions like it doesn’t matter if a massive oversupply of some asset class has been created and that nominal prices can remain high indefinitely.

What a two-bit joker.

The fact that DeLong comes up with a “Marx-Hayek” school should tell you something about his confusions and fantasies, as well as, his sophistical polemical positioning. But saying that he can make no basic sense of malinvestment and overaccumulation is quite astonishing coming from a highly credentialed economist. It’s really basic production economics. In order for anything to be exchanged, it must first be produced, (yes, that’s Adam Smith). And the production system of an economy must be vertically integrated in correct ratios, regardless of whether that occurs through market exchanges between firms or through infracorporate transfers at administered prices, and intersectorally balanced, since different industries produce inputs for each other long before they produce final consumption outputs, if the production system is to be reproduced, let alone expanded, in its output. That bottlenecks and imbalances should occur in the overall production process is hardly surprising, since it is by no means fore-ordained, and subject to varying macroeconomic conditions, and techical changes in processes and products that raise the level of productivity, (though, note, not necessarily in a balanced way through the production system), and alter, refine and diversify distributable, consumable output. But, ultimately, all increases in real distributable surpluses, i.e. profits, flowing to financial assets as legal-claims on the distribution of those increases in productive surpluses, derive from the realization of real capital investment in the organization of production processes through revenue derived from the sale of output. Now the real distributable, consumable surplus product, real “wealth”, consists in the total product minus that portion of the product that is consumed or used up in the process of its production, (though that would include services and symbolic artefacts, as well as, more-or-less physical goods), and it is divided up and distributed between profits and wages in a inversely proportional relation, a simplification of empirical revenue streams, but basically true. (The using up of raw materials, depreciation of capital stocks and subsistence wage are all subtracted from the total product to get the surplus product). If the wage rate is too high the replacement and/or improvement of capital stocks is impaired and the economic system can not reproduce, let alone expand. If the rate of profit is too high, then there will be a shortfall in real effective aggregate demand, hence over-production, excess capacity, and underconsumption, which will devalorize capital stocks, lower profits and lead to a contraction of the production system. In principle, there would be a sweet spot in the distribution between wages and profits, labor and capital, that would optimize the production of output and the balance of the whole system, but due to constantly changing technical conditions of production, that optimum itself constantly is changing through macroeconomic cycles of economic conditions. The role of the financial economy is simply to intermediate between firms and households in maintaining the “virtuous” cycles of growth in the real rpoductive economy, under constantly changing conditions and economic and technical ratios. But note that increases in productivity, while increasing potentially the real distributable surplus product, which can raise wages for remaining workers, in the short-to-medium-run, increase unemployment of workers, which must be redeployed elsewhere, and eliminate outmoded techniques and sectors, which requires that new sectors much ultimately be formed. And, on the other hand, profits must be reinvested to produce further profits, else there will be an overaccumulation of profits competing against other profits, a deterioration in the rate of profit, and a decline in the value of financial assets, (as the price goes up through increased competitive demand, the yield goes down), together with a devalorization of real capital stocks, which decreases the incentive toward new real investment and threatens a disaggregation of the production system with mass unemployment and further declines in aggregate demand. That is a capital realization crisis in the real productive economy through overaccumulation of capital and excess productive capacity. Such a crisis can be deferred through an increasing financialization of the real economy, in which debt-financed consumption and increased demand for financial assets to prop up their prices, increases claims on future output, but unless new avenues and sectors for real capital investment and employment are discovered in the process, that merely results in an increasing stock of fictional capital, that is, financial assets whose nominal “value” increasingly exceeds the real productive capacities of extant capital stocks and their replacement costs and the revenues to be realized therefrom, and only encourages increasing financial rent-seeking activities, as “profits” are minted from profits, without attachment to costs of production in the real economy. Ultimately such stocks of fictitious capital must be destroyed to rebalance the production system and to reestablish viable ratios between wages and profits that can sustain its further growth. But that’s not a pleasant prospect, in the meanwhile.

The upshot is that issues of malinvestment and overaccumulation are endemic to industrial capitalism, though in varying degrees through economic cycles and technical development, and are not simply to be wished away though some technocratic wizardry manipulating nominal prices. I’m just gobsmacked that DeLong could claim not to understand such basics through abstracting out from them through a theory of macro-economic general equilibrium which is, er, speculative at best. (Similarly, I’m struck how much effort conventional neo-classical academic economists expend on determining and touting “financial efficiency” with respect to, say, relatively small differences in inflation rates, while ignoring the transition costs of large imbalances in the production system). Granted, in this age of financial and industrial globalization, it’s no longer possible to speak in terms of a model of “an economy”, but that’s all the more to the point, since the global CA imbalances are glaring, as are the misallocative effects of them in terms of fictive housing values and wage stagnation. What DeLong feels entitled to ignore in his modelling defies belief.

In fairness to Delong, if I grasped his point, he is modelling a specific point: that under certain conditions, lenders will not further offer mortgage loans, regardless of how high the interest rate would go in response to excess demand for loans. It’s in that context that he proposes that the government needs to back-stop loans, not to prop up asset values, but to correct for market failure in the market for mortgage loans, which might be required to facilitate housing transactions and thus housing price adjustments. But that would be beyond the capacity of the FED and would require the fiscal capacities of the overall government. And there are definite costs to be associated with increasing the fiscal indebtedness of the U.S. government/economy. I’m one that believes housing prices need to come down to affordable levels and basically the sooner the better, but fiscal intervention might be required to maintain the liquidity of that process, provided it doesn’t prop up excessive house prices, nor swallow the losses of financial institutions. As well as reform BK law, (so that the asset-inflated complacency of the middle class would get its comeupance without total ruin), I like Dean Baker’s proposal of allow the option of converting foreclosures into rentals, which might help to mitigate the worst social effects of the housing meltdown without interfering in price adjustments much, (which would otherwise overshoot anyway, which would be a kind of inefficiency), which probably would require a federal fiscal backstop, with the government as landlord-of-last-resort, without bailing out the rent-seeking follies of the finance sector. I’m unclear on the exact legal and administrative means by which such a program could be instituted, but at least their the costs of increased fiscal endebtedness are counterbalanced with a real good, without impeded unduly price adjustments.

I think it is fair to say if that enough people had paid attention to Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek in the first place, our financial system and economy wouldn’t be in nearly the calamitous state that it is in right now.

People make a point of emphasizing the need for “free markets”, and yet the most important price of all—the price of money—is centrally planned. The gigantic irony is watching central bankers (i.e. central planners) like Greenspan and Bernanke talk about the virtues of free markets. Funny how the media never noticed the ridiculous irony of this all the way along.

How can you have a “free market economy” when the price of money is centrally planned?

My first visit here – impressed by Yves and comments; so good to read well considered and thought out statements, rather than superficial claptrap.

IMHO as a non-economist is that the proximate cause of the household credit problem that needs to be resolved is the fact that increases in household income for so long have lagged true inflation. People simply had to make ever more debt in order to maintain their life style. Two possible non-mutually exclusive solutions would be: a) increase household income (and SS pensions!) to make up for the lag in income (inflationary) and b) lower prices until households can afford to live adequately on their regular income (deflationary.

As long as the disparity between actual income and actual inflation exists, there IMHO cannot be a permanent solution to the mess and many more Bears will continue to crawl out of the woods in search of resuscitation.

The underlying cause of the problem IMHO goes back to political pressures that brought about a policy of disguising true inflation (and thus artificially boosting GDP)in order to justify a lax monetary policy in expectation of economic ‘growth’ that would put the Administration in a good light and ensure the president a second term – referring to Clinton, who knew exactly what he had to do to be re-elected following the success of his “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Combine a need to make new debt with increasingly easy means to do so and a credit bubble was assured – as was the current consequences.

Closer to Bear: it would seem true that if Bear was allowed to fail, too many other dominoes would have toppled as well – this despite the (once-held?) view that derivatives offered a way to diversify risk.

One wonders to what extent the lax approach to derivatives regulation was intended to allow the financial sector to compensate though greater activity for the loss to GDP of the decline in manufacturing production in the US. Or was a blind eye turned to the risks in order to assist the financial sector recover from the scares of 1997/98? This of course presupposes there were people in authority who were able to recognise the risk.

The common factor in the above two comments is that official policy in pursuit of near term expediency, as a rule, sooner or later invokes the Law of Unintended Consequences. It is a lesson that politicians appear endemically incapable of learning.

– daan in SA

De Long’s description of the mortgage crisis—“irrational pessimistic panic”—is pretty rich. Surely he’s not suggesting that MBS holders who paid for AAA and got CCC are irrationally refusing to buy more? Or that homeowners are rushing to sell, rather than walking away from liar loans? This isn’t a panic, it’s a collapse brought about by a Minsky ponzi scheme.

Steve

Brad and Larry S. are statists, the leftish version of Bush’s neo-cons. It drives thought and actions, whether it be censoring thought to which Brad disagrees even if presented factually and in a polite manner (I will delete it because I “know” it is wrong) to creating a more intrusive government or as in the case of larry trying to ride roughshod over a university faculty

http://jessescrossroadscafe.blogspot.com/2008/03/where-are-we-today-where-are-we-going.html

I’m not saying its wrong, per se, but it drives their approach to problems and the character of their solutions.

i am not an economist ( come from sciences ) and as such unable to make a reasonable comment on the issue involved .

i do use to read delong ( and few other donkey partisans years ago but gave up . they suck to use common language ) but gave up after his dishonest attacks on prof.chomsky . he hates chomsky’s criticism of US empire and the colonial project aka state of israel .

how ever when i did read him what struck me most was his reverence to greenspan . almost always reminded me of lewinsky on all four in oval office .

Yves,

Totally agree that it is ad hominem attack in particlular the “slogan” broadside

“competent government that keeps asset prices from being pushed into fire-sale territory by irrational pessimistic panic”

No, a competent government doesn’t promote artificial “wealth”, brand it innovation, market it as a productivity miracle (or cold war dividend of capital freedom as Greenspan claims!) and then drone on about how it is the sustaining competitive advantage of the US, when in reality the social economic construct is a patchwork of rotting geopolitcal and geoeconomic policies, whose near era lifeblood, low interest rates, ameliorates the eroding standard of living with a subsitence wage subsidy in the form of plasma TVs and Scion crossovers. The only thing Hayak about this post is the title of his book: Road to Serfdom!

” I think, be no doubt that the world was enormously enriched by the constructions of the quinquennium from 1925 to 1929″

Yes I suppose if you frame 1998-early 2000 in the same way it is technically true – although we will need another decade plus or so to see if the Nasdaq can match the performance of the Dow circa 1930s. As Yves so aptly says, the benefit of hindsight is well a benefit.

“Marx-Engels-Hayek-Smith line of argument does attempt a parry. It says that the root problem is overproduction–that we have too many houses.”

No, there is too much credit, equities, housing, treasuries, CDS are but derivatives (no pun)…Academic rot.

I’d be interested, though have a good feel for what to expect, in his cost benefit analysis of the following FT article about the I-banks looking to ring fence assets like UBS. RTC II here we come. If bear Stearns was an outrage WAIT unitil the details of these scheme become public. Sad day for America.

Agreeing in part with commentator S (no pun intended) ; it’s not the job of governments to maintain mirages at all costs. As for the UBS scheme, isn’t it just super SIV redux? Sounds like “now u see it, now u don’t” mentality, distressed assets funds are probably getting into their zebra suits right now and making the beeline for tall grass; not a good time to be a scavenger when you have no idea what the heck those steaming piles are

“I find it difficult to accept that he would be so closed minded and petty as to delete posts/comments that disagree with him. Is this really true?”

Yes it’s true. I have seen him delete posts that were on topic, polite and short. I have experienced it myself. What’s more he will do it without comment– the post simply disappears down the memory tube. Of course it’s his blog and he can do what he wants. Likewise we are free to ignore him. He also sets a poor standard for his students by engaging in excessively insulting remarks about people calling them “stupid” and unfit to hold their jobs.