Monoline insurers were last year’s story, but I have a prurient interest in some of the smoldering hulks of the credit crisis.

Readers may recall that in January-Feb of last year, seemingly imminent demise of monolines looked to be ready to set off financial armageddon, since monoline (and AIG) credit enhancement was critical to a lot of structured credit instruments. The theory was if the monolines lost their AAA ratings, a lot of parties that held credit enhanced paper would have to mark it down or sell it at a loss (some buyers had bought AAA paper for regulatory reasons, and they were presumed to need to ditch it if it were downgrades).

The monolines, despite their protests that they really were OK, were nevertheless eventually all downgraded. To a degree, they had a point: many of their guarantees pushed payout out so far into the future that their public financials (on a mark-to-market basis) did paint an unduly harsh picture. The flip side was they had guaranteed a lot of toxic dreck, and even if they might not have to pay out on it till 2050, many investors decided they were no longer comfortable with their business model and headed for the exits. And since the rating agencies were insistent that they raise more equity , the stock price whackage was a bit of an impediment.

Even with hindsight, it’s hard to parse out the role the meltdown of the monolines had in the greater unravelling. The increase in agency spreads in late February 2008 seemed to be the immediate trigger for the Bear Stearns implosion, but the fate of the monolines was hanging in the balance then too, and probably played into a destructive dynamic.

MBIA had some special features that made it a standout the generally sorry monoline story, and not in the positive sense. It had a captive reinsurance operation that looked sus. And it had a particular fondness for the most dubious structured credit paper, collateralized debt obligations.

CDOs are resecuritizations. They take the bottom tranches of bond deals (for RMBS, the BBB through junior AAA slice) and put them in a new vehicle and tranche it up again. The problem, as we saw with subprime, is that if the risks of the bonds are really not that diverse, the resecuritizaton serves to concentrate rather than reduce risk, particularly if the real risk is macroeconomic rather than a local/regional downturn.

So the monoline got themselves into a world of hurt thanks to writing guarantees on CDOs based on dodgy residential mortgages.

And the next iteration is likely to be CDOs with heavy exposure to commercial mortgage backed securities (by contrast, ones composed of whole loans would not be as troubling, since a CDO made of whole loans is functionally equivalent to a commercial real estate mortgage backed security, or a CMBS. It’s a first, not a second, generation securitization).

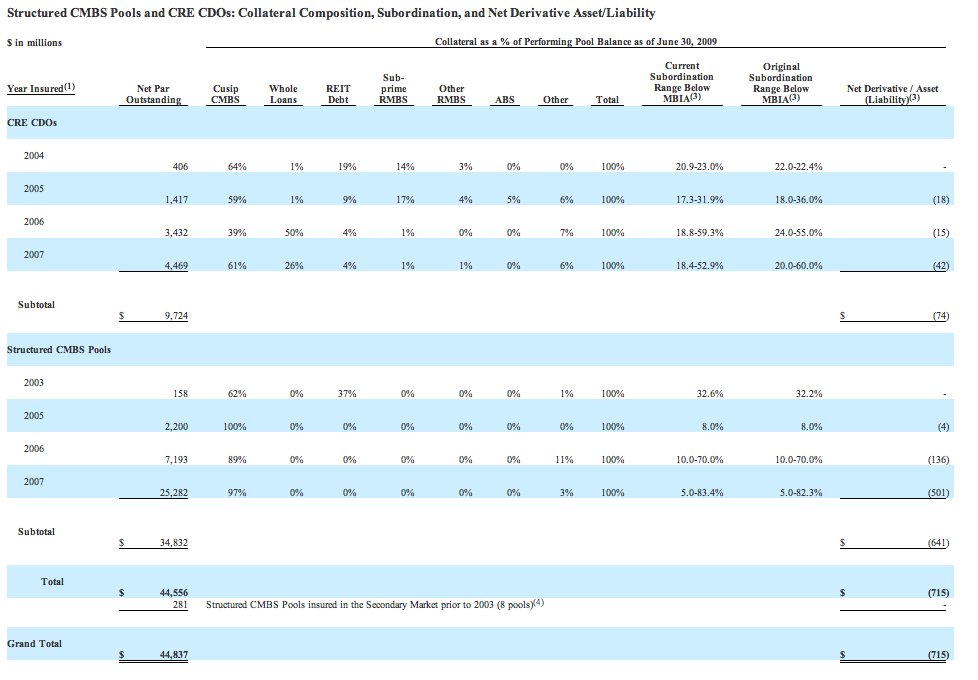

And as you can see, MBIA has a lot in the way of commercial-real-estate-related CDO exposures, a whopping $45 billion (click to view full chart, hat tip reader Scott):

One reader, CDO Trader, noted:

… similar to the old ABS CDOs, the CMBS bonds [in the CDOs] were usually mezz-y. Those deals could have catastrophic losses in a few years…. Also, take a look at how active they were in 2006-2007! It looks like as AIG slowed down, MBIA grabbed the reins. I always knew they had a lot of garbage, but even I was shocked when I read that report!

To translate: “mezz-y” means composed of heavily of mezzanine (BBB) tranches, which is not a good thing.

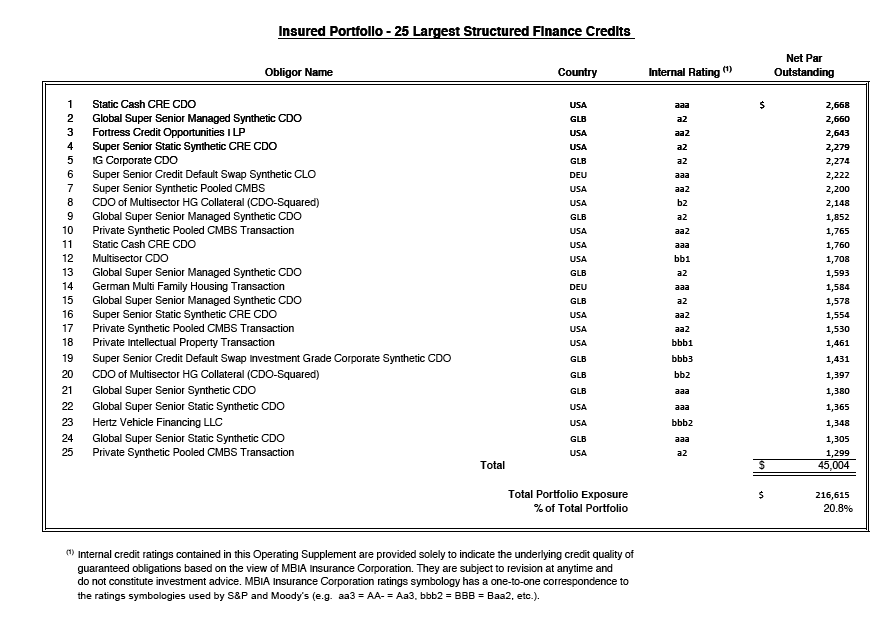

Another MBIA factoid: they are, amazingly, counting some CDO squareds as being worth something north of zero, see item number 20 (click to view entire table).

Need I say more?

“Another MBIA factoid: they are, amazingly, counting some CDO squareds as being worth something north of zero, see item number 20 (click to view entire table).”

Could you please clarify this paragraph? Thanks

A CDO is usually composed of the lowest (meaning weakest, riskiest) tranches of a structured security. Most CDOs made of asset backed securities were complete wipeouts. The AAA tranches trade for zero or 20 cents-ish on the dollar, depending on the type.

CDO squared are made of the less than AAA tranches of CDOs. They pretty much have to be worth zero.

If there is no insurance company, how can you possibly be paying for insurance? They are only worth the insurance fees they gather from the munis.

There was a story a while ago about the monolines splitting into separate commercial/govt entities. Why would they ever let that happen?

MTM has been far too kind to MBIA. The valuation allowance has reduced it by over $10B. This is based on an absurd quirk in fair value accounting that allows near-bankrupt companies to steeply discount liabilities. In addition, MBIA engages in a variety of shifty accounting that further reduces the MTM.

As you note, the CRE exposure is very vulnerable from a structural standpoint. It probably does not matter very much, because MBIA’s residential mortgage related liabilities are enough to put them under. Shifty accounting (i.e., fraud) is the only thing reason MBIA’s financials say the company is adequately capitalized.

The CDO^2s are not pretty, but the risk might be less than you think. These include a fair amount of structured finance CDOs as collateral (20%-25% or so), but the remainder is mainly high rated tranches of corporate CDOs and CLOs, which appear to be in much better shape than than similar RMBs tranches. To put this in terms you have used, most of the exposure is “second generation” (like a typical structured finance CDO) rather than “third generation” (like a CDO^2 made up of subordinate structured finance CDO tranches). Some of the other CDOs (the ones MBIA is suing Merrill about) are quite a bit worse than any of the CDO^2s.

Yves, thanks as always for your excellent commentary.

I know I’ve heard this espoused by many insurance companies and banks ad nauseum, but the idiosyncratic structure of each CDO is very important, particularly as pertains to cash flow diversion mechanisms. It’s unlikely that 100% of the collateral of all their CDO^2s has already gone non-performing, so to the extent that MBIA built in sufficient safeguards it’s not unreasonable to expect that they might receive some amount >0% of par.

I am confused. If it is a well known fact that a CDO has the lowest tranches, why were they rated AAA? I was thinking a good percentage(70% – 80%) of a CDO contains Prime mortgage and the remaining is sub-prime obligations. Giving the rating agencies an front to rate them AAA. Isn’t this true? Can anyone elaborate? Thank you.

Srini, the answer in short is financial alchemy, the key reason that the rating agencies are in trouble. First they turned junk into AAA (subprime and Alt-A RMBS), and then they took the junk of the junk (subordinate RMBS tranches) and called it AAA. Then they rated the monolines AAA even though they were leveraged beyond belief with the junk of the junk. Unfortunately, the “magic” of structured finance does not really work.

A typical structured finance CDO wrapped by MBIA and other monolines looked something like this.

10% AAA RMBS

35% AA RMBS

30% A RMBS

5% Other ABS (CMBS, auto and credit card deals)

20% CDO (mostly structured finance)

The RMBS had a variety of labels (e.g., sub-prime, Alt-A, prime), but for the most part it is a pile of junk. In many of the deals, the “prime” collateral has performed worse than subprime, because it took less in terms of losses to wipe out the collateral.

The structured finance CDO collateral was usually rated highly at inception (more often than not AAA), but it is much worse than the RMBS collateral. Most has now defaulted with 0% likely recovery.

Thanks a lot Mark! I have been reading this blog for over eighteen months now and learnt a great deal from it (from Yves as well as from the comments section).

I knew CDO’s were bad but only to the extent of 30% of any given CDO. And the common refrain I heard is that they have become illiquid and they are still performing reasonably well. But this explanation make it clear that they are totally junk.

Wow! if CDO’s are this bad I can see why Yves made that remark about CDO Squared.

I’ll qualify what Mark says. Although other comments are right, CDO structures varied a lot. On the residential mortgage side, they were often classified as either a “high grade” CDO, which had a structure more like the one Mark described, which the tranches in the CDO were junior AAA through A, or “mezz” CDOs. Mezz CDOs were the dumping ground of BBB tranches. Monolines were wrapping (as in credit enhancing) them too.

So when CDO Trader (who is currently in the business of valuing them) says a deal is “mezz-y” that means it is heavily exposed to the weakest trances and likely to become a big zero.

Yves, you have no idea what you are talking about with regard to CDOs. Stick to what you know best, whatever that is.

Ambac wrapped the senior tranche (originally AAA-rated) of a large mezzanine CDO^2. This was pieced together mainly with subordinate tranches of mezzanine CDOs. To put this in perspective, losses on these might be in the 85% range on average, and the CDO^2 is made up of pieces in the 10%-40% loss range. Holders will see partial interest payments trickle in for a couple of years, but the odds of ever seeing a cent of principal are pretty remote. (Yves or CDO trader, if anything is off about what I am saying, it would be great if you could let me know.)

Some of Pershing Square’s presentations on MBIA walk through the basics of these structures.

Oops. I copied my post from Word and some of it got cut off.

I also said that I have never worked in the securities industry, so take what I say with a grain of salt. In late 2007, when I first learned about these structures, I became fascinated with how these Frankenstein’s monsters ever came into existence, how they got high ratings, and how they found buyers.

The CDO structure that was outlined in my prior post is often referred to as a “high grade” CDO. MBIA wrapped some mezzanine CDOs, mostly from 2005 and prior, but the biggest, ugliest deals are the 2006 and 2007 “high grade” deals.

RL, rather than making an unsupported nasty comment, why not educate us?

In response to RL who sounds like he must work for Barclays or one of the many IAs who structured CDOs to shill to their clients during the heyday…one of the reasons that the super-senior tranches were given AAA-ratings was because they were supposed to be ‘over-collateralized’ meaning that even with aggressive default assumptions (for the time), there was a very low chance that those tranches would not get repaid. Note that the rating was a probability that the principal associated with a particular Note (bond) would in fact be returned to the investor eventually, not of the timing thereof, or whether any interest/divvies would ever get paid on the tranche. The rating agencies were quite clear about this, although the salespeople were not and the traders of course were downright indifferent as they were paid on a yearly basis so had little concern for problems that might not arise until several years after a trade were booked.

Another reason that the super-senior tranches were so improbably highly-rated was that they were supposed to be highly diversified and therefore have reduced ‘correlation’ risk. This was a b.s. term that meant that because the mortgages/bonds that comprised the CDO tranche were from different areas of the country, different industries, hell, from different borrowers, the odds that they would all default at once were greatly reduced.

CDO-squared structures were CDOs of CDOs, meaning that the underlying notes/bonds were not in fact collateralized by individual mortgages or corporate/government bonds but rather by the notes issued by other CDOs.

So while some of these comments imply that all CDOs’ super-senior tranches are in default or should be priced near zero, or at least rated as junk, that is probably not the case, although I’m not following them closely. On the other hand the notes of the CDO-squared CDOs may very well all be ‘in the tank’ particularly if the included some of the non-super senior tranches from those CDOs.

Hope this is helpful… .

To clarify on CDO squared and CDOs generally. I had wanted to avoid this, but…

A zero from MBIA’s standpoint is not the same as a zero on the bond.

There is most definitely interest-only value in these super senior CDO positions, but that does not accrue to MBIA, it actually hurts them.

In the CDO waterfall, the super senior AAA, junior AAA, and AA coupons are paid first with the interest generated on the collateral. If that is insufficient to cover the coupons then principal proceeds are used. What happens in these really bad deals is that there is not enough interest comming off the collateral to pay the freight on the senior liabilities, so you start to burn through your principal to pay interest. Unlike RMBS deals, the bonds aren’t “written down” in order to have asset par = liability par. In other words the true seniority of the bonds goes:

SS AAA interest

Jr AAA interest

AA interest

SS AAA principal

Jr AAA principal

AA principal

So if you wait 15-20 years, the unpaid coupons defer and grow exponentially, which turn into a liability large enough to suck away any bits of principal that occasionally come in, which means the par value of the super senior AAA will never be reduced, ergo the losses at maturity are 100%. That is why there is decent value in the cash bonds, a 5-10 year interest only is quite juicy, but unfortunately for MBIA that comes at their expense.

Yeesh. CDO is the general term for a securitisation. A CMO for example is a type of CDO. SF CDOs are resecuritisations (ie a securitization of already securitised CFs). A CDO is not “usually” comprised of anything. There are many, many variations: cash/synthetic, funded/unfunded, market value/cash flow, single-tranche and so on.

The rating process is highly complex. It is not financial alchemy, whatever that means. It cannot be proven that it concentrates risk. Please read the report linked below for clarification (Note: I do not work for Moody’s. The other agencies have similar models, I just picked this report as an example).

I do not work for Barcap (although I have taught classes there on securitisation as a consultant). In fact, I used to structure (shill) these things years ago and have spent the better part of the last ten years teaching bankers, investors and MBA students how these and other complex financial products work, including an understanding of risk/return parameters.

The problems with these products was and is straightforward: they are overly complex, too difficult to model/value and generally overpriced as (1) the rating agencies until recently did not have sufficient data to accurately rate downside risk and (2) investors’ risk tolerance reached extreme levels prompted by global low-yield, low spread environments.

My unsolicited advice once again: do your readers and the investment community the service you intend and stick to what you know rather than oversimplify complex products without possessing both (1) the source material to substantiate your statements and (2) the industry experience necessary to present yourself as an authority in this area.

http://www.moodys.com/cust/content/content.ashx?source=StaticContent/Free%20Pages/Products%20and%20Services/Downloadable%20Files/MDYS%20Approach%20to%20Rating%20SF%20CDOs.pdf

RL,

OK, point by point

“Yeesh. CDO is the general term for a securitisation. A CMO for example is a type of CDO. SF CDOs are resecuritisations (ie a securitization of already securitised CFs). A CDO is not “usually” comprised of anything. There are many, many variations: cash/synthetic, funded/unfunded, market value/cash flow, single-tranche and so on.”

All true. If you cut the writers some slack on the context, however, all irrelevant pedantry too. And no more than a display of Wikipedia-level insight, to boot.

“The rating process is highly complex. “

I think you meant “The resecuritization process is highly complex”. You seem to be having some trouble keeping track of Yves’s points here. Do try to keep up.

“It is not financial alchemy, whatever that means.“

I have a funny little feeling it might be a metaphor for a highly complex resecuritization process that often doesn’t work. Again, you could cut some slack here.

“It cannot be proven that it concentrates risk.”

Yes it can. You need to be able to exhibit the existence of embedded leverage that compounds with each iteration of securitization.

“Please read the report linked below for clarification (Note: I do not work for Moody’s. The other agencies have similar models, I just picked this report as an example).”

You don’t think, given Moody’s track record of expertise in rating CDOs, that this document might be something of a false friend, when it comes to establishing your credentials? Thanks for the disclaimer, by the way.

“I do not work for Barcap (although I have taught classes there on securitisation as a consultant). In fact, I used to structure (shill) these things years ago and have spent the better part of the last ten years teaching bankers, investors and MBA students how these and other complex financial products work, including an understanding of risk/return parameters.”

Looking back at the last couple of years in the financial markets, how well did that teaching effort go, do you think? Specifically, the risk/return bit; anything you’d want to tighten up on, in hindsight?

“The problems with these products was and is straightforward: they are overly complex, too difficult to model/value and generally overpriced as (1) the rating agencies until recently did not have sufficient data to accurately rate downside risk and (2) investors’ risk tolerance reached extreme levels prompted by global low-yield, low spread environments.”

Is this the sort of stuff you taught at BarCap? “Overly complex”, huh? Couldn’t you have just mailed them in a Wikipedia link, with a covering note, and taken the money? “Overpriced”. Your diagnosis is that CDOs were “overpriced”. ARE YOU SHITTING US???

“My unsolicited advice once again: do your readers and the investment community the service you intend and stick to what you know rather than oversimplify complex products without possessing both (1) the source material to substantiate your statements and (2) the industry experience necessary to present yourself as an authority in this area.”

Pot, kettle, yawn.

Not that I would describe Yves as a kettle.

RL,

While I appreciate your comments, I am well aware of the differences between funded vs. non-funded, synthetic v. hybrid v. cash, and single tranche.

I also find it interesting that you chose to mischaracterize what I said to “prove” your superior knowledge. What I said in the original post was accurate. If the CDO is a resecuritization (as in it is made of tranches of loan securitizations, typically of MBS, rather than whole loans, as is the case with some CRE CDOs and all CLOs) AND the pool process does not diversify risk very much, which certainly happened with ABS CDOs, particularly the mezz variety, you have in effect concentrated risk. Mezz ABS CDOs are a prime illustration. Now you can argue that the mezz ABS CDO experience is not representative of other CDOs, but that does not make the statement I made less valid.