The February report from the Congressional Oversight Panel makes for sobering reading. It forecasts $200 to $300 billion in losses coming from commercial real estate loans, and notes these were not considered in the famed stress tests, since that process looked only through 2010, when the losses from CRE will peak later.

Some snippets (hat tip reader Richard Smith):

The health of the commercial real estate market depends on the health of the overall

economy. Consequently, the market fundamentals will likely stay weak for the foreseeable

future. This means that even soundly financed projects will encounter difficulties. Those

projects that were not soundly underwritten will likely encounter far greater difficulty as

aggressive rental growth or cash flow projections fail to materialize, property values drop, and

LTV ratios rise on already excessively leveraged properties. New and partially constructed

properties are experiencing the biggest problems with vacancy and cash flow issues (leading to a

higher number of loan defaults and higher loss severity rates than other commercial property

loans).94 Falling commercial property prices are increasing debt-to-equity ratios, decreasing the

amount of equity the borrower holds in the property (putting pressure on the borrowers) and

removing the cushion that lenders built into non-recourse loans to protect their original

investments (putting pressure on the lenders).

Yves here. Construction loans can and will deliver large losses. Even though construction loans require interest payments during the building and lease-up/sales period, this is all a finesse, since the interest is paid out of the loan balance. So a lender on a construction project that has come to look dodgy has unattractive choices: he can try to foreclose by finding a covenant violation (he will hopefully recover some of the yet-to-be spent proceeds but be stuck with a partially completed project) or allow it to be completed and face the high odds of foreclosure later (completed project but not capable of repaying the loan). And given that the prices of commercial properties have fallen by an average of 40% and have further to drop, the loss severities will be steep.

The report has lots of useful factoids, like how the loans are distributed across the banking industry and total size of market ($3.4 trillion). But here are the money quotes:

Between 2010 and 2014, about $1.4 trillion in commercial real estate loans will reach the

end of their terms. Nearly half are at present ―underwater‖ – that is, the borrower owes more than the underlying property is currently worth. Commercial property values have fallen more than 40 percent since the beginning of 2007. Increased vacancy rates, which now range from eight percent for multifamily housing to 18 percent for office buildings, and falling rents, which have declined 40 percent for office space and 33 percent for retail space, have exerted a powerful downward pressure on the value of commercial properties.The largest commercial real estate loan losses are projected for 2011 and beyond; losses at banks alone could range as high as $200-$300 billion. The stress tests conducted last year for 19 major financial institutions examined their capital reserves only through the end of 2010. Even more significantly, small and mid-sized banks were never subjected to any exercise comparable to the stress tests, despite the fact that small and mid-sized banks are proportionately even more exposed than their larger counterparts to commercial real estate loan losses.

A significant wave of commercial mortgage defaults would trigger economic damage that could touch the lives of nearly every American. Empty office complexes, hotels, and retail stores could lead directly to lost jobs. Foreclosures on apartment complexes could push families out of their residences, even if they had never missed a rent payment. Banks that suffer, or are afraid of suffering, commercial mortgage losses could grow even more reluctant to lend, which could in turn further reduce access to credit for more businesses and families and accelerate a negative economic cycle.

It is difficult to predict either the number of foreclosures to come or who will be most immediately affected. In the worst case scenario, hundreds more community and mid-sized banks could face insolvency. Because these banks play a critical role in financing the small businesses that could help the American economy create new jobs, their widespread failure could disrupt local communities, undermine the economic recovery, and extend an already painful recession.

There are no easy solutions to these problems.

The headline of the post is slightly misleading. The pain in CRE is all around me and has been for two years. The pain for the CRE *lenders* is just in the early stages. Extend and pretend is finally starting to wind down. A lot more recaps and foreclosures going on right now than six months ago.

Actually, I beg to differ. The working out process will drive prices lower. And the Reinhart/Rogoff work says that in severe financial crises, real estate prices take over five years to bottom. Even if their work was biased towards residential real estate, I can’t imagine the CRE cycle being dramatically different (as in yes its cycle can be shorter and more severe, but I don’t see it being dramatically shorter).

And your two year figure claim is an exaggeration. In late 2007-early 2008, people were still debating whether CRE would suffer a crisis:

In November 2007, a Moody‘s report and a Citigroup analyst‘s note both predicted

falling asset prices and trouble for commercial real estate similar to the crisis in the residential

real estate market.73 Other experts sounded an alarm about commercial real estate as part of a

broader alarm about the worsening of the financial crisis. In testimony before the House

Financial Services Committee, Professor Nouriel Roubini predicted that ―the commercial real

estate loan market will soon enter into a meltdown similar to the subprime one.‖74

This view was by no means unanimous. During late 2007 and early 2008, a number of

commentators challenged the assertion that the commercial real estate market was in crisis, and

anticipated no collapse.75

The Roubini remarks were as of Feb. 2008. “Soon enter” is not the same as “already in”.

With all due respect Yves, unless you are on the streets making CRE deals you wouldn’t know that, as the first comment correcttly asserts, the CRE crisis began about two years ago. The first sign was the spike in shadow inventory and drop off in lease activity across all food types. This was followed by increasing vacancy and availability, which is only now translating into defaults. Only because financial institutions and special servicers have been given every incentive to extend and pretend with changes in Bank Regulators guidelines as to how to classify performing loans, FAS accounting rules, and to some extent taxt treatment of REMICs for “imminient default” situations.

The patient got infected long ago, only now are we seeing the nasty symptoms of the disease.

By the way, there is no good real estate out there to buy. All the good stuff is getting bid up and the garbage you can find in a wrapper with and stamp FDIC on it.

What do the Harvard professors say about that?

How about ‘a meltdown similar to the subprime one?’

Is that the same as ‘pain in CRE all around me?’

I guess we will never know.

The Congressional Oversight Panel appears to agree with your assessment that the “pain for the CRE *lenders* is just in the early stages.”

Late in the COP report the panel makes the following grim forecast: “There appears to be a consensus, strongly supported by current data, that commercial real estate markets will suffer substantial difficulties for a number of years.”

No one should worry about overestimating potential losses on incomplete CRE construction.

So a lender on a construction project that has come to look dodgy has unattractive choices: he can try to foreclose by finding a covenant violation (he will hopefully recover some of the yet-to-be spent proceeds but be stuck with a partially completed project) or allow it to be completed and face the high odds of foreclosure later (completed project but not capable of repaying the loan).

Experience here in SW Florida to date is that foreclosed incomplete projects don’t have low market value. They often have no market value. Google “Tringali Auction” in Sarasota FL. And note this event occurred three years ago in February, 2007. When I saw those results I understood there was almost unlimited downside in all r.e.

Such properties actually represent standing cost sinks. Taxes still accrue, cleanup requirements are present and liability insurance has to be maintained if the subsequent owner has any net worth at all. And if anyone wants to resume construction they’ll find they have to pay off the original architects, civil and structural engineers first. These folks were typically screwed along with everyone else.

Unless the new owner wants to do full site demolition$ and $tart over with completely new plan$ and a new permitting proce$$.

Notice that the king of incomplete condo projects in Florida, Stephen Ross of the Related Companies, has gathered a billion bucks together to buy a bank. I was wondering how the company, which is private so who knows what the hell it does, was going to survive being the largest condo developer in the largest condo market at the height of the largest real-estate bubble ever. Now we know; he’s going to buy a bank and stick all his bad loans in there. Kinda like a personal Fannie/Freddie model. Hey, it worked for GS.

One of the biggest consequences of the collapse of commercial and residential real estate values will be to municipalities, county, and state governments. Once the inevitable challenges to valuations work their way through the system, the governments will be coming up short. Are they going to make it up with sales taxes? Income taxes?

While there are no easy solutions, we would be a lot further ahead and looking at less overall pain if we would have not done the bailouts in 2008. The “savvy” financial giants in control have not saved us from a depression they have only insured that it will be worse than it needs to be.

IMO, after this train wreck is accepted for what it is there will be clarity about where valuations will end up but until then they will just go down.

On top of the economic losses, we can also thank the reckless banksters for a blighted urban landscape. The blizzard litter of lease signs, weedy lots and vacant buildings is already thick, but absent visionary leadership and a purposeful urban policy agenda, I imagine our cityscapes could begin to resemble Mexico’s backwaters of crumbling half-finished hopes with plywood windows and rusty rebar stubble. Doubly depressing.

When you note losses of $200-300 billion, is that leveraged into trillions by the time taxpayers bail the casino bastards out again? And is it even possible to bail the leeches out this time, or is the prospect of sovereign more default likely?

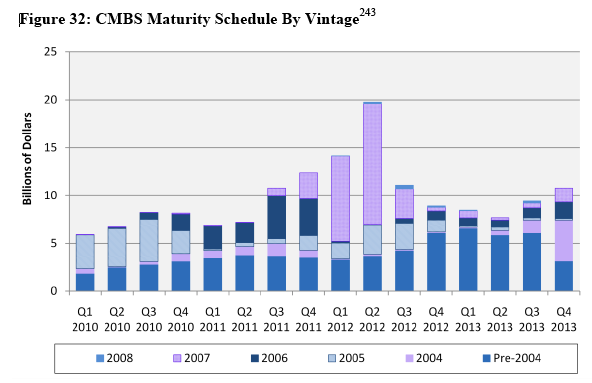

So, just so I keep my sequencing correct…CMBS’ tend to be sold in approximately 5 year maturities followed by 10 year. In 2007 there appears to have been a spike in 5 year, followed by a collapse in 2008. Does this decline reflect the volume of loans or the market for CMBS’? Are the originators holding a large volume of loans made in 2007 that were made to be securitzed but couldn’t be, or did they turn off the spigot quickly?

What does a congressional oversight panel know about anything, never mind real estate capital markets? More on that below, but first – Suffern ACE, the bulk of CMBS loans are 10 year maturities, there are also 5 year maturities and a smattering of 3 year delas. The CMBS deals that are sold to investors package all these loans together so there is not one “maturity” date for the security per se.

Investors typically talk about CMBS deals in terms of average life, which reflects both the tenor (length) of all the underlying loans as well as the size of the loans. These investors all ran for the hills in late 2007, so the decline reflects the market for CMBS paper, not the appetite for credit in the borrower pool. Indeed, lack of credit across the lending spectrum is one of the primary causes of today’s high default rates in CRE.

Most lenders stopped making CMBS loans in Q3/Q4 2007. One of the last CMBS deals to get sold was a June 2008 JP Morgan Chase deal, and it was chock full of 2007-vintage loans. 20% of that deal’s collateral was in default within 6 months of issuance. Did they know something?

Which brings me to the first and third comments in this thread; these comments are correct. CMBS paper turned to cement almost overnight in late 2007. Nobody would trade it, and nobody would buy it. I remember talking to CMBS traders in November of 2007. They said “nothing is moving, everything has stopped”. I also remember they were very, very fearful, particularly the Lehman guys. That is when the commercial real estate crisis began, and it cascaded from there. Deal volume dried up due to lack of credit, and prices began to fall. Then the Great Recession took hold and vacancies skyrocketed, followed promptly by plunging rents. By early 2008, this was all in full swing, and frankly, those of us in CRE could see it all coming back in 2006. And it’s true, Class A and B properties in primary markets are attracting 20-30 bids, some from as far away as Germany and South Korea.

Congress should stick to shoveling snow. We taxpayers are paying for all this brilliant prescience, and very often we don’t get much for our money!

Yves is right. I am both a landlord and a renter, and I just bought a new stove for the apartment I rent in San Francisco. I also have residents living in apartment buildings I own and manage in the Midwest re-doing their floors and kitchens.

Not only that, as a property owner, if I do not maintain and upgrade my property, I cannot compete effectively for renters like Yves (or me). Thus, all renters indirectly drive capital investments in real property, and they do it constantly. To assert otherwise is simplistic and naive!

It is a widely accepted belief, and one that seems not only commonsensical, but supported by observation, that a renter of a property is not in the least bit interested in putting any of either their time/money into upkeep/maintenance of the property in which they reside.

Yet as an economy falls more and more into the hands of a rentier class, and the same degradation inevitably occurs, no one can understand how this can happen.

This is one of the reasons globalization and its attendant pillaging of national economies will continue unabated. The ultimate enabler and member par-excellence of the rentier class are the banksters:

Who, as described in Joni Mitchells’ “Dog Eat Dog”, are:

people looking, seeing nothing,

people listening, hearing nothing

people lusting, loving nothing,

people stroking, touching nothing,

people talking, knowing nothing.

This leads to what we have: AIG: all is gone.

No, that isn’t true.

I live in a rental in NYC (I have owned co-ops twice, the second experience was a horrorshow). In my building, many people, including your blogger, have spruced up their apartments, stuff that amounts to capital improvements. One woman on the 14th floor spent well over $1 million.

Why? As long as you are current on the rent, under the rent regs relevant for this building,the landlord cannot deny you a lease renewal.

The fact that you can’t be capriciously thrown out by the landlord if you are upholding your end of the deal leads to very different behavior.

Similarly, in one rental house we lived in when I was a kid (we moved a lot, in this town, housing market was tight, no suitable houses available for purchase), my parents redid a small downstairs bathroom and wallpapered their bedroom. We were going to live there long enough that it made sense. They might have gotten a small concession from the landlord, but I am sure they bore most of the costs.

Yves is right. I am both a landlord and a renter, and I just bought a new stove for the apartment I rent in San Francisco. I also have residents living in apartment buildings I own and manage in the Midwest re-doing their floors and kitchens.

Not only that, as a property owner, if I do not maintain and upgrade my property, I cannot compete effectively for renters like Yves (or me). Thus, all renters indirectly drive capital investments in real property, and they do it constantly. To assert otherwise is simplistic and naive!

The more I read (here and elsewhere), the more I get the sinking feeling that the recession is not nearly over. It seems we’re in the eye of the storm and the second wave could be much worse than the first. Is it just me?

No.

If the medias don’t talk about it anymore, it doesn’t mean that its over…

Seriously…