By Richard Smith, a UK based capital markets IT specialist, and Yves Smith

It’s always a fraught business when a foreign paper hazards into parsing UK politics. But one has to wonder at the unseemly spectacle of the Grey Lady giving such a distorted reading on Mervyn King, the governor of the Bank of England.

Were you to rely on the New York Times story on Monday, “A Crisis of Faith in Britain’s Central Banker,” you would think that this central banker is under assault on all fronts. While most of the article is on his fiscal/monetary policy stance, where King is taking a great deal of criticism, it also leads readers to believe he is isolated on bank reform as well. These are the first and third paragraphs of the piece:

A central banker need not be loved, but at the least he should command respect — and in Britain these days Mervyn King cannot count on either…

As for the issue on which he may have most closely staked his reputation — that Britain’s large banks must increase capital levels well beyond international standards — he so far has been ignored.

At the very close of the article, the Times’ account can again be read as doing a disservice to King on the regulatory reform front:

Mr. King has also attracted a strong following — largely outside British banking circles — for his aggressive campaign to reduce the leverage of Britain’s banks. He laid out his case in a hard-hitting address late last year in New York.

As Mr. King pointed out in that speech, Britain’s banks pose unusual risks because they have assets 4.5 times the size of the British economy. How to scale that back is the subject of a much anticipated independent inquiry here, led by John Vickers, a former Bank of England chief economist and head of the Office of Fair Trading.

Mr. King has been careful to not prejudge the result. He has made clear, though, that his view is that radical changes must come, saying in his speech that of the systems one might use to organize banks, “the worst is the one we have today.”

It’s a bit weird to juxtapose a comment that King’s fanbase is outside British banking circles with a speech given in New York. It has the effect, perhaps deliberate, of reinforcing the notion stressed in the rest of the article, that King is fighting a lonely battle here as he is with his macroeconomic policy stance.

In fact, King has been a pointed and persistent critic of bank conduct and a staunch advocate of wide ranging reforms in all of his policy statements during and after the crisis. He not only has support from other regulators, notably the FSA’s Adair Turner, who has been scathing in some of his remarks, and Andrew Haldane and other senior Bank of England figures, but also politicians: not just from the centre-left Deputy Prime Minister Clegg, but also the (admittedly gormless) Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne too.

Peculiarly, the Times piece stated explicitly that King was alone in wanting to shrink the banks (reducing their leverage would have that effect). John Vickers has already made statements that are very much in accord with King’s stance. For instance, there is very serious discussion in the UK of “structural reform” of which the prevailing model is a Glass-Steagall type division of banking into retail versus capital markets/institutional banking arms. Notice how this idea, which died in Dodo, ahem, Dodd Frank, is getting virtually no coverage in the US media. It appears we can’t let the citizenry know that a country whose banking sector is a bigger proportion of GDP than ours is not afraid to take on its financiers.

Excerpts from a recent speech by Vickers, which was carried in full at the Telegraph:

One of the roles of financial institutions and markets is efficiently to manage risks. Their failure to do so and indeed to amplify rather than absorb shocks from the economy at large has been spectacular. The shock from the fall in property prices, even from their inflated levels of a few years ago, should not have caused havoc on anything like the scale experienced. Rather than suffering a ‘perfect storm’, we had severe weather that exposed a damagingly rickety structure.

Contrast this with the consensus reading of the FCIC report: everyone was at fault, so you really can’t say the crisis was the fault of the big financial firms.

Back to Vickers. Even though he voices a concern during his speech that the obvious means for strengthening bank balance sheets are less than ideal, he closes the speech with a firm endorsement of Mervyn King’s general position:

It cannot be disputed that banks of systemic importance need much more loss-absorbing capacity than they had a few years ago, and to be much more easily resolvable. There is a wide range of views on how much more loss-absorbing capacity is appropriate for different kinds of institution, and on how to achieve it by equity, contingent capital, etc.

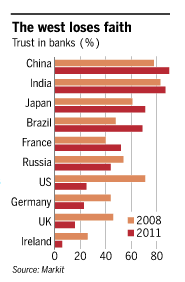

King’s hard on the banks stance enjoys even more popular support in the UK than just about anywhere, as a survey of 5000 “well schooled, wealthy and ‘well informed'” respondents, meaning card carrying members of the international elite, confirms (put it another way, if members of your own class are not on your side, it might be time to rethink your strategy). And it’s not easy to write it all off as “bonus envy”, either: the press consensus on the need for reform extends from the left to the right; such doubts as there are about the imminence of reform are usually couched in terms of “political will” (for which you can read “we won’t be able to get the Americans onside”).

Now none of this is to say that the Bank of England governor is suffering from a want of opponents. Merv is, to an almost comical degree, not always a big maker of friends. If you are looking for Merv critics you do indeed have a particularly target rich environment of late, because he has been speaking his mind, rather a lot:

According to the latest WikiLeaks revelations, the ambassador reported that:

King expressed great concern about Conservative leaders’ lack of experience. [He] opined that party leader David Cameron and shadow chancellor George Osborne have not fully grasped the pressures they will face from different groups when attempting to cut spending.

Then there was the wonderful long-running public punch-up between King and one of his (ex-) Monetary Policy Committee members (the interest rate setters), David Blanchflower, which, ahem, simmers on, as you might well conclude from an article by Blanchflower entitled Mervyn King must go:

Mervyn King is one smart guy and that has always been abundantly clear. Unfortunately, it is his thirst for power and influence that has clouded his judgment one too many times. He has now committed the unforgivable sin of compromising the independence of the Bank of England by involving himself in the economic policy of the coalition. He is expected to be politically neutral but has shown himself to be politically biased and as a result is now in an untenable position. King must go.

During my time on the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), King made it abundantly clear that members should not comment on fiscal policy and should stay out of party political matters. He has failed to follow his own advice…

King confirmed my long-standing view that on economic policy the coalition is totally out of its depth…

There were insights, though, in the embassy documents that I found truly shocking, not least the details of King’s attempts to co-author the coalition’s strategy on the deficit…

And this information emerged only a few days after revelations by Adam Posen at the Treasury select committee that members of the MPC were uncomfortable that statements King had made were overly political. The Financial Times, in a recent article, made it clear that others on the staff at the Bank shared that view. The governor of the Bank of England should not be in the business of shaping one political party’s macro-economic policy.

Mervyn King should consider his position. It’s time for a change at the top at the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street.

Despite the level of vitriol (which is not all that unusual in British politics), the political charge, that King overstepped the Bank of England’s remit, is more of a tempest in a teapot. By contrast, the fact that economic policy appears to be going more than a bit off the rails is a more serious problem for King. Heretofore, the UK looked to have done much better in navigating the crisis than the US; its unemployment rate is a tad lower at just under 8%, and its GDP growth was less anemic despite having a top-heavier banking system than that of the US, until a surprising reversal in the 4th quarter of 2008. And the latest inflation readings look alarming, though some still contend that the spike up may be transitory.

And the Times appears disinclined to question the economic and political challenge facing King. It is bad enough that austerity is misguided (the dramatic falls in GDP in Latvia and Ireland which have actually worsened their debt burdens relative to earning power, are proof that trying to starve your way to prosperity simply does not work). The more successful playbooks, ironically, come from countries in the far north: the Scandinavian countries in the wake of their early 1990s banking crises, and now Iceland. Recognizing the banking system losses increasingly appears a necessary condition to getting back on track with recovery; by contrast, Ireland and the UK are still coddling the banks by allowing them to carry dud assets at fictive values (the US and UK are also using slack monetary policy as another sop to the banks). And austerity again seeks to validate debt of questionable value, and hence is another subsidy to the banks. It’s curious that neither King nor the Times recognizes the contradiction in his stance.

But irrespective of King’s response to the economic policy challenges facing him, it does seem very peculiar that the Times went out of its way to depict King as far more isolated than he actually is on the issue of financial system regulation. The UK has been and continues to be the only country that makes serious-sounding noises about bank reform. And given that our model is called “Anglo Saxon” around the world, the UK should serve as an important reference point for US policy. Given there is little meaningful opposition in the UK to King’s stance on reform measures outside the City of London, one has to wonder exactly who sold the New York Times on the bank-serving notion of depicting his as a lone champion of tough rules.

You are correct. Mervyn King is not isolated. Au contraire, he has a lot of support for seeking to rein in the banks.

The U.S. banking lobby is full of B/S and it has spread its poision round the world, not least to its willing accomplices in the City of London.

Mervyn King is to be applauded.

Another good reason why I refrain from reading the Times when i wish for serious comment.

As much as I disagree with King’s macro policies (established inflation is more dangerous to households than slightly higher interest rates – ir expenses are more or less constant, while inflation is compounding), I believe he’s pretty good on the structural banking problems. I’d even say better than any other CB, but that would be a meaningless comparison.

As for support for that – he even gets some from people in the City, believe it or not.

“the dramatic falls in GDP in Latvia and Ireland which have actually worsened their debt burdens relative to earning power”

I’m not convinced that GDP is the best measure of a countries wealth anyway – it takes into account too many non-value added transactions.

This government report (http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/53572.pdf) suggests that GDP increased in part due to the september 11th attacks and hurricane katrina – both events I am sure you will agree were not actually beneficial. From the report:

The economic effects of Hurricane Katrina have also been compared to the terrorist attacks of September 11. The attacks came during the 2001 recession, which began in March 2001, and ended in November 2001. In the third quarter of 2001, national GDP declined by 1.4%. It is likely that third quarter growth would still have been negative had

the attacks not occurred.

and

Although damage to the capital stock does not reduce measured GDP, rebuilding increases it. Some of the regions that take in victims will see their growth rates rise as the victims receive government relief spending and, in some cases, obtain employment in their temporary city. Moreover, there is likely to be an increase in construction spending in the quarters and years to come in the affected area

Much of the austerity measures being put in place are attempting to reduce wasted and unnecessary time and effort in an attempt to to (ahem)encourage people into more value added wealth creating jobs rather than public sector beaurocratic time wasters.

i dont understand how glass-steagall banks will compete against ‘universal banks’ like deutschebank and ubs. let alone against government-involved banks like those of China.

wont the small banks just get bought by the bigger banks?

Don’t know how the data stacks up in the UK, but in the US it is very clear. This “you need to be big to compete” is pure bunk. Big banks are MORE costly to run per dollar of assets (admittedly only slightly so, but this has been studied a zillion times and the studies always come to the same conclusion).

And that’s even when you include their funding advantage from being TBTF. The consolidation is driven SOLELY by executive comp. The top guys at big banks get paid more.

Yves, Nick Clegg is not centre-left. And George Osborne is not remotely serious about structural reform.