Cross-posted from Credit Writedowns. Follow me on Twitter at edwardnh for more credit crisis coverage.

Here’s an interpretation of the euro zone I have been meaning to discuss. I touched on it in the update to my post on how austerity in Europe works. In a fixed exchange rate environment like the euro area, you don’t have currency fluctuation issues. So persistent current account imbalances as we see within the euro zone are really a form of vendor financing. I am familiar with the perils of vendor financing having witnessed the Telecom bubble of the late 1990s go bust, wiping out the major source of revenue in the European high yield market in which I worked. Here’s an article from right around the bust that gives you a positive spin on how how vendor financing worked in telecoms.

Aerie is just one of the 45 vendor financing deals Nortel has on its books. As such, it offers a glimpse into a battle the big telecommunications equipment makers — notably Nortel, Lucent (LU) and Cisco (CSCO) — are rushing to join: picking up more of the financing slack for the very companies that buy their equipment.

Islands in the Stream

While Nortel is certainly knee-deep in the lending business, rival Lucent is the true champion of vendor financing. Lucent has been saying "yes" ever since it hit the ground four years ago, to the tune of $7 billion in financing commitments, more than double Nortel’s $3.1 billion. (Nortel has $1.4 billion in actual loans outstanding to buyers of its equipment; Lucent, $1.6 billion.)

Cisco, in order to compete with the incumbent telecom equipment makers, says it has beenincreasing its vendor financing activities through its banking arm, Cisco Capital. Cisco has so far promised $2.4 billion in loans to its customers. (Cisco’s loans outstanding amount to $600 million.)

Equipment makers derive several advantages from so-called vendor financing arrangements, the terms of which often remain under wraps. Namely, they gain relationships with potentially lucrative customers and revenue that will look good on the next financial statement.

Vendor financing works successfully as long as the lender makes sure the customer can pay back the loans. In the telecoms arena, the whole sector cratered and these loans were an albatross around the necks of the likes of Nortel and Lucent. Not only did firms like Nortel lose huge revenue streams, they also had to write off massive amounts of capital from dud loans they had made to customers during the bubble. It’s as if most of the revenue Nortel and Cisco were booking in 1998 or 1999 was phantom revenue, maintained artificially by their channel stuffing and vendor financing of customers. Eventually Nortel went bankrupt.

And so it is in Europe as well. The lurid Telegraph story about German-made Porsches bought in Greece shows you an extreme example of how this works. The reality is you can’t have Germany and Spain both running current account surpluses with each other at the same time. Unless the euro zone as a whole runs a current account surplus as large as Germany and the Netherlands, then you are automatically going to have a sort of vendor financing relationship going.

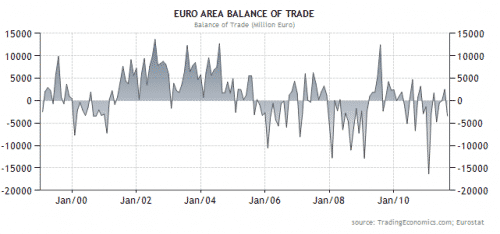

The euro area did have a good-sized trade surplus through 2005 – not as large as the one that Germany and the Netherlands had, but sizable. This all unravelled starting in 2005 (chart below via tradingeconomics.com). That would have been the time for German banks and companies to pull in their horns and restrict credit to the periphery.

So, if Germany or the Netherlands wanted to be the export juggernaut and run a massive current account surplus, this had intra-EU ramifications. The most important is that Germany’s or the Netherlands’ current account surplus matched current account deficits in Spain, Portugal, and Greece. That’s how it works. You sell more to me than I do to you and I get more cash than you do. There are always two sides to every transaction (chart from the FT below).

The large euro-area internal current account imbalances should be seen as a form of vendor financing, whereby the creditors, principally Germany, forward their customers, the debtors, trade finance in order to sell their wares. Germany’s aging society meant slow growth. So German companies have looked abroad for growth, just as the Japanese have done in their aging society. Taken in aggregate, this means persistent current account surpluses which are a fancy way of saying vendor financing at the national level.

German banks were at it too, by the way. German retail banking is a low margin business and credit growth is weak. So the German banks loaded up on foreign assets, making loans abroad. German banks were very active in Ireland and Spain during the housing bubbles there, for example.

So, one way to look at the sovereign debt crisis is a complicated form of vendor financing. German banks have been particularly aggressive in seeking returns abroad and now the chickens are coming home to roost.

I covered the EU vendor finance issue here: http://thebuttonwoodtree.wordpress.com/2011/10/14/vendor-finance-german-entanglement-as-illustrated-by-ge-capital/#comments

When a vendor finances the purchase of goods, payment should be booked as a current (or long term) asset, not receivables. Hence, when you consider the widespread nature of German vendor finance, German businesses’ are dependent on the credit of their customers. It’s like a giant SIV, and the credit rating of the vendor should really reflect the credit of its customers, given the dependence.

Reminds me of GE Capital, to use another example.

I agree that vendor lines of credit could in some cases be considered assets, although in a few cases they may already be, as in where there is a separate financing arm. But whether or not they are considered to be receivables or general assets, there certainly are accepted practices for assessing them in terms of creditworthiness, delinquency rates, etc., and taking write-downs as appropriate.

I would think that in many cases, it is not the classification of the loans that is the problem as much as an overly rosy view of likelihood of repayment. If you extend a vendor loan knowing or suspecting that only 80% of your customers are ever going to repay, you really should not be booking full profit up front, but rather take an immediate discount to your earnings based on what you believe regarding rates of repayment.

Credit driving GDP?

Skippy…or their about’s?

I agree with your description up untill 2007. Since then there is no more vendor financing. The current account deficits of the GIIPS countries are all financed by the ECB, through the TARGET payment system.

I stand ready to be corrected, but I believe that Edward’s point is that the Eurozone as a whole is, in effect, acting as vendor financier for its producing nations of Germany and the Netherlands.

I would argue that the same thing is happening, only more indirectly, in the U.S.; that heavy borrowing by the U.S. government is propping up consumption in the U.S., much of which is going toward foreign-produced goods. Foreign manufacturers are able to continue production even as their holdings of U.S.-originated debt pile up, with the open question being whether it will all get repaid.

However you look at it, the main reason is that a common currency, the euro is flawed from the very start when countries have different competitiveness. If you compare Italy’s and Germany’s industrial productivity during the years 1990 to now, you see that the curves are fairly similar until 2000 and then they gradually diverge until the difference is over 30% now. Meanwhile, the cost of labour has increased in Italy whereas it was fairly stagnant in Germany during the last 10 years.

So, when the cost of labour increases and the cost of capital stays the same (euro), no wonder the recourse to borrowing was the easy way of compensation, leading to today’s unbearable situation. Obviously, removing Berlusconi will not change this one iota.

I therefore predict either a huge catastrophe is not managed properly (by whom?) or an orderly exit from the Eurozone by Italy, Greece, Portugal, Ireland. France is the big question mark.

I don’t see any reason for Spain to stay in the euro in that case, though I think you simply forgot it. Spain is in a lot of ways the biggest basket case of IIPS.

This post should mandatory reading for all those person who believe that it is possible for all countries to have cuurent account surplus and that any country that does not have an current account (export surplus) is financially inferior.

Nice Post.

BIGGER IS NOT NECESSARILY BETTER

The Telecom Bust, as you call it, was not a question of Vendor Financing (whatever that means) but EU competition policy directed by Brussels.

It was a conscious policy of the European Union to dismember the Incumbent National Telco’s to privatize them. The consequence was that the telecom suppliers were forced to reorganize since national telecom companies no longer could demonstrate national preference (for equipment purchases) contrary to an open, competitive market.

This happened when the Internet was changing telephony systemically. From POTS to VOIP was then in its infancy and now it is gaining predominance. And it will go still further as copper wires are replaced by fiber-optics, the pipeline necessary for all forms of media (telephony, video and text).

So, all in all it was a good thing – quite unlike the US, where MaBell became regional quasi-monopolies that retained large portions of their market share. In fact, DSL-connection costs are higher in the US than in Europe for this very reason.

I was “there” too when all this came about. The old elephants of telephony are mere shadows of themselves, which means only one thing. Without a national monopoly, they could not exist.

What’s the lesson for both Europe and the US? That “bigger is not necessarily better” for as long as it leads to market integration that become quasi-oligopolistic with a select few sharing the market and setting prices higher than would otherwise exist if that market were truly competitive.

But, of course, regulatory oversight of market competition is performed by the Dept. of Justice, which reports to the PotUS. So, neuter regulatory oversight and the PotUS is effectively handing a very large check to those who helped with the election funding …

And who pays for consequences? Jack ‘n Jill Consumer.

Another example of oligopolistic markets is that of Health Insurance in the US. Why is American private health-care insurance three to four times more costly than the same in European National Health Systems?

Because there is no real competition in insurance providers. See this info-graphic here. Note the number of states where the percent of people insured by only the top two insurers is more than fifty percent.

“Vendor financing works successfully as long as the lender makes sure the customer can pay back the loans.”

Exactly.

Vendor financing has long been known to be an accounting/operations gimmick used to artificially increase earnings. There really is nothing to it: companies can easily book illusory profits by locating weak credits who are willing to buy their product on ultra-easy credit. An automobile manufacturer offering 0% financing is going to find a lot of ready customers, particularly if it ignores their credit histories. But how many of those booked profits will actually be realized?

The problem is when it comes time to repay the loans. As Edward highlighted, the tech bubble collapse exposed many vendor-financing schemes to be losing operations for the companies running them. When vendor financing is extended and customers cannot repay, it results not just in a decline in profits, but even in massive losses, as they lose not just the cost of the goods produced, but even of the financing charges. The customers get free goods and the producer pays the full price for both those goods and the financing. What exactly is the point?

Vendor financing for customers who cannot repay is not trade financing, it’s charity.

Lucent was huge in vendor financing long before it got bought by Alcatel. They had a history of pumping sales by providing credit to non-creditworthy customers, and this drove them into the hands of Alcatel rather than the bankruptcy court. The marketing VP in charge of this fiasco, by the way, was none other than Carly Fiorina. This was the success that propelled her to HP.

Any current account surplus, anywhere in the world, is equivalent to vendor financing for the rest of the world, in the form of the associated capital account deficit.

I have been desperately waiting for someone to explain how the current accounts imbalances (caused by vendor financing) are the cause of sovereign debt. Krugman has been alluding to it but I think describing this accurately is very politically potent.

I am guessing commercial credit became to risky about 2007 so German banks made the Greek state an intermediary, using it’s credit rating to pump up Greek consumer demand.

Please help me clarify this!

I think it’s difficult to consider a cause-and-effect, but it is more approachable to consider how the cycle feeds on itself.

Consider: Germany and Greece join a monetary union, with an implication (denied by the various leaders, but still there) of financial support from Germany for Greek loans. Greece therefore enjoys more favorable borrowing terms courtesy of implied support from Germany, that allow the state to borrow more and at better rates.

Greece borrows money -> borrowed money paid by the state to pensioners -> pensioners buy luxury goods from Germany -> German manufacturers book profits

That’s a simplification, but I don’t think it’s far off. Germany is providing implicit support for Greek loans, as well as aggressive buying of Greek debt by German banks, which allows Greece to distribute loan proceeds to its citizens as part of social welfare programs, which in turn is spent on goods imported from Germany made by German manufacturers. It isn’t direct vendor financing, but it has the same effect.

I’ve been reading that the Greek median income has been flat thru this while the mean has soared. Was it the pensioners and labor who benefited? Or did politically connected insiders make off with sweetheart government contracts? (then proceeds were sent to offshore banks)

I honestly don’t know, although I cannot think labor benefited much, given the unemployment rate, the size of the “unofficial” economy, and the relatively high proportion of the populace working in or dependent on the government.

Extend the vendor financing analogy to the US housing bubble, but subsitute the USG for the telecoms, and GDP for the telecoms artificially pumped up revenue.

Not supposed to subsidize your own industries and give them an unfair advantage in global trade agreements so the next best thing is to merchantilize your own citizens. Yesterday’s joke about the German Inn Keeper was to the point. If you can keep money circulating it all works. But the weakest link isn’t a refundable deposit, (the trick would simply fail and vendor financing would never be anything more than a test drive). The weakest link is the consumer’s promise to pay no matter what. Based on a hope and a prayer. If the consumer, like the homeowner, is never hedged but every other step in the transaction is hedged on the shoulders of the optimistic consumer and even the state participates in this nonsense, it’s cannibalism. Unless the consumer has a job security and good health care.

This analysis is way too too simple.

First, the EU is not a closed system, so you can’t claim that a trade surplus of one country is at the expense of a trade deficit of another as many seem to suggest. Most of the rise in exports from Germany for example went outside the EU.

Furthermore, you need to look at the whole picture per country to see what really happened. And it’s different for each.

For example: Spain had a housing bubble, others didn’t like Italy.

Some countries get most of their borrowing from inside the country, like Italy, others rely on other EU countries financing them like Greece.

Some banks in some countries (for example France) were very active lending money to countries like Greece, banks in most other countries hardly did lend money to Greece, even in a surplus country like The Netherlands.

Most of the Southern European countries have seen a large increase in exports since the euro, but even more imports because they made the mistake to borrow too much because of the low interest rates since the euro. In other words: the cause is not lack of competitiveness or lack of exports, they simply lived beyond their means.

All eurozone countries were supposed to bring down deficits, in particular the Southern countries should have been able to bring them down with the lower interest rates they got compared to before the euro, but instead some like Greece, but not all, like Spain, abused to low interest rates to borrow even more.

Furthermore you need to distinguish between private and public debt situations that differ per country. Some have large private debt like Spain, but also a surplus country like The Netherlands, because of housing bubbles, others like Italy have low private debt but high public debt.

In some countries the high public debt already existed before the euro: Italy got into the euro with a government debt above 100% of GDP, close the the current level, and much higher than the Maastricht treaty allowed (60% of GD)). Etc. etc.

summarizing, it’s a complex picture. Yes, there are imbalances, but most of the problems of the current mess should never have happened if regulators and politicians would have been more careful and paid more attention or sticked to the rules. If they would have done so, we might have been in a very different situation today.

The main culprit was too much borrowing, at too low rates. You only need to look at the UK and USA to see that the EU was not alone in this. It was new economics speak from Greenspan and co that claimed that debts didn’t matter anymore.

So why are bond rates so high in eurozone countries, but low in USA and UK? I think because UK and USA monetize debt.

BTW: a real example of vendor financing is the USA – China relationship.

You throw in so many technical details that don’t really amount to anything to refute the central point of the article. Frankly I got lost about half way.

Then, you definitively calls the USA – China relationship a “real example of vendor financing,” while ignoring the fact that there are a whole lot of minute and not-so-minute technical details in the transactions there as well, involving other East Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea and Taiwan, among whom there are trade deficits and surpluses. Do you even know that Japan has a large trade surplus against South Korea? That transaction is completely intertwined with the US – China trades as well. The situation there is a lot more complicated than you think.

And let’s stop this myth that “Some countries get most of their borrowing from inside the country, like Italy”. “Most” means anything only when it’s as “most” as Japan or Canada, as these countries even flat out REFUSE foreigners trying to buy their bonds. And I don’t know how you missed the large amount of Italian government bonds that the French banks hold.

It is not only the banks. The export credit agencies were at it too. My feeling is that the ultimate losses on the renewables financing in southern europe will end up bigger than the subprime crisis in the US.