Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of the Telegraph, who correctly called that ECB would not take action last week, argues in his latest article that Mario Draghi and Italy’s Mario Monti have isolated the Bundesbank and are closing in on being able to buy bonds along side the Eurozone rescue facilities once the ESM presumably goes live (the assumption is that the German constitutional court will lift its injunction on September 11). Draghi hopes to keep Mr. Market at bay till then by a combination of happy talk and threats.

We noted that members of Merkel’s party (but neither Merkel herself nor finance minister Schaeuble) said it might not be so terrible for the ECB to buy bonds provided there was “conditionality,” meaning recipients were relegated to subject nation status via the IMF-like procedures of the ESM and forced to wear the austerity hairshirt. But they did not sign off on having the ECB go full bore. My German-reading sources parsed their statements and took them to approve only of buying short-term bonds, and then only in limited amounts. So while this is a crack in the facade, this is not as big an opening as Draghi wants.

Evans-Pritchard reports that Draghi has also secured commitments to allow him to buy bonds from all the northern Eurozone central bankers ex Weidmann of the Bundesbank:

The Bundesbank’s Jens Weidmann is isolated. The Dutch and Finnish governors backed the Draghi plan. So did Germany’s member on the ECB’s executive board, Jörg Asmussen. The Kanzleramt has lost patience with the ideological preening of the Bundesbank.

Mr Draghi has secured a mandate for “unlimited open-market operations”, a far cry from the half-hearted and self-defeating bond purchases of the last two years. The ECB at last has a licence to act with overwhelming force, like the US Federal Reserve.

I have not gotten confirmation from my sources, due to the hour, that they’ve seen indications that the other central bankers indeed agreed to “unlimited” operations, as opposed to a specified amount. While Evans-Pritchard may well be correct, the opposition heretofore was not just ideological. Past bond buying had proven to be a short term expedient. After the ECB stopped intervening, periphery country rates went on to reach new highs.

Even with this shift, Evans-Pritchard points out that this plan is fraught, and a periphery country has power over the Germans via a threat to leave the Eurozone (this is admittedly a mutual assured destruction strategy, but with the northern bloc calling for slow strangulation, not just of them but of Europe as a whole, brutal near-term dislocation might well be lest costly in all-in, and it also would preserve some semblance of democracy).

This update by Delusional Economics, by contrast, focuses on some of the immediate hurdles that the ECB must surmount to put its plans into effect.

By Delusional Economics, who is horrified at the state of economic commentary in Australia and is determined to cleanse the daily flow of vested interests propaganda to produce a balanced counterpoint. Cross posted from MacroBusiness.

Last week I speculated that Mario Draghi, the ECB president, was unlikely to deliver on his London promises due to a number of roadblocks. On Thursday markets fell sharply on just that but by Friday, after supportive statements from members of the Merkel’s coalition, they re-evaluated the statements and rallied sharply upwards. I’ll leave the analysis of market schizophrenia to others.

From an Australian perspective this is all quite bizarre. It is difficult imagine that Australians would accept comments from Glenn Stevens on the funding of government programs, especially when the underlying premise of the statements were to grant greater power to his own organisation. But I learned long ago that Europe needs to be viewed outside that prism.

What I found most interesting about Mr Draghi’s statements, and following Q&A, were that they appeared to be a strong continuation of the ECB’s step across the Rubicon into the arena of politics and fiscal policy in order to force Europe’s politicians to break the ‘chicken and egg’ stand-off.

Mr Draghi hinted that this was on the way in his now famous London speech in which he once again outlined the vision for the future of the Eurozone:

A Europe that is founded on four building blocks: a fiscal union, a financial union, an economic union and a political union. These blocks, in two words – we can continue discussing this later – mean that much more of what is national sovereignty is going to be exercised at supranational level, that common fiscal rules will bind government actions on the fiscal side.

Then in the banking union or financial markets union, we will have one supervisor for the whole euro area. And to show that there is full determination to move ahead and these are not just empty words, the European Commission will present a proposal for the supervisor in early September. So in a month. And I think I can say that works are quite advanced in this direction.

As you may realise, the Europe of today is quite distant from this dream and the continent continues to struggle with the politics of such a transition. I’ve been talking about the chicken and egg situation in Europe for a long time and although July’s summit looked as though there was finally some progress there has been major backtracking since that event. I suggested back in early July while analysing some collateral rule changes by the ECB that the central bank appeared to be turning up the heat on politicians to take the next steps:

It is a jawboning operation by the ECB to force national governments to ratify the ESM/fiscal compact. A long bow maybe, but the amendments state that these changes only matter for public sector entities “with the right to impose taxes” which doesn’t include either the EFSF or the ESM. As I mentioned earlier in the week, the fiscal compact is intertwined with the ESM and these changes potentially close down back-door funding to banks via the ECB.

That being the case I don’t think it is unfair to surmise that the ECB understood that this change would put pressure on national governments to ratify outstanding economic treaties.

Although this certainly wasn’t the first time that the ECB had taken bold steps that could be interpreted as being outside its monetary policy mandate, this is the first time that Mr Draghi has shown that he considers all sides of the debate to be the problem, including those from Germany.

I do, however, think that in the same way markets got a bit ahead of themselves early last week on the back of the London statements, they’ve done the same again with Thursday’s words. I’m not saying that Mr Draghi’s statements weren’t important, they certainly were, but Mr Draghi himself was very clear in his answers after his statement that there was still some ways to go:

But, it’s clear and it’s known that Mr Weidmann and the Bundesbank – although we are here in a personal capacity and we should never forget that – have their reservations about programmes that envisage buying bonds, so the idea is now we have given guidance, the Monetary Policy Committee, the Risk Management Committee and the Market Operations Committee will work on this guidance and then we’ll take a final decision where the votes will be counted. But so far that’s the situation; I think that’s a fair representation of our discussion today.

…

There is no reason to be specific as far as further non-standard measures are concerned because the other part of the guidance is that the relevant committees should examine the other possible measures.

…

It was not a decision. It was guidance; it was a determined guidance for the committees to design, as the statement says, the appropriate modalities for such policy measures.

As we’ve seen before, the technical details are extremely important and we are yet to see exactly what tools will be enacted. Mr Draghi said in reference to the SMP that the “the concerns of private investors about seniority will be addressed”, but that doesn’t change the fact that the ESM treaty still states:

Like the IMF, the ESM will provide financial assistance to an ESM Member when its regular access to market financing is impaired. Reflecting this, Heads of State or Government have stated that the ESM will enjoy preferred creditor status in a similar fashion to IMF, while accepting preferred creditor status of the IMF over the ESM. This status shall be effective as of 1 July 2013. In the unlikely event of ESM financial assistance following a European financial assistance programme existing at the time of the signature of this Treaty, ESM will enjoy the same seniority as all other loans and obligations of the beneficiary ESM Member,with the exception of the IMF loans

So in my opinion there are still some significant technical points that need to be dealt with and I also expect political backlash. Let’s call a spade a spade here, this is quite obviously a power grab even if it is hidden under the guise of economic management.

Those points aside, the structure of what Mr Draghi has proposed is quite clearly jawboning of both sides of the economic divide to force a resolution. Although we have heard promises from Germany that they will support the periphery after they enact fiscal reform the ECB now appears to be calling their bluff. In open defiance of the Bundesbank and some in the German political camp the President offered the possibility of open ended and unsterilised bond purchases:

Regarding sterilisation, you should not assume that we are not going to sterilise or that we will sterilise – you have to understand, these operations are complex and they affect markets in a variety of ways. So the relevant committees will have to work and tell us exactly what is right and what is not right, so it’s too early to say whether they are going to be sterilised or not sterilised. Rest assured that we will be acting within our mandate, which is to preserve price stability in the medium term for the euro area. That must always be taken into account.

Third point, regarding whether it’s unlimited or limited – we don’t know! Basically, the Introductory Statement – and I am really grateful to the Governing Council for this – endorses the remarks that I made in London about the size of these measures, which need to be adequate to reach their objectives.

Meanwhile he is also calling the bluff of the periphery by making it very clear that this is completely dependent on compliance from southern nations on enactment of the fiscal compact:

The first point is very important because we want to repair monetary policy transmission channels and we clearly see a risk, and I mean the convertibility premium in some interest rates. But the Governing Council knows that monetary policy would not be enough to achieve these objectives unless there is also action by the governments. If there are substantial and continuing disequilibria and imbalances in current accounts, in fiscal deficits, in prices and in competitiveness, monetary policy cannot fill this vacuum of lack of action. That is why conditionality is essential. But the counterparty in this conditionality is going to be the EFSF. Action by the governments at the euro area level is just as essential for repairing monetary policy transmission channels as is appropriate action on our side. That is the reason for having this conditionality.

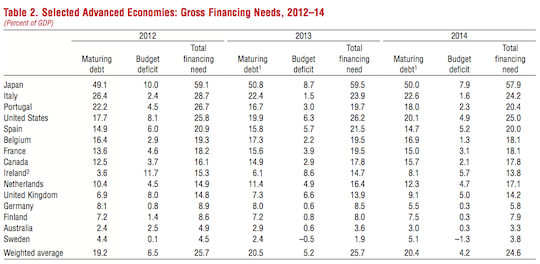

So technicalities aside the big question now is will the bluff work? Obviously this is a question for after September 12th as until the ESM is ratified by the German constitutional court much of this is irrelevant. Mr Draghi, however, may have given a big enough kick to Europe to get them through the quiet holiday period in the meantime. Both Spain and Italy appear to have baulked at the idea, with Spain stating it will wait to assess further and Italy saying it doesn’t need the money at all, but as you can see from the chart below there is a long road through to 2014.

Of course, the question for myself and the citizens of Europe is exactly what this is all in aid of. The wrangling around what comes first makes interesting political analysis but ultimately it is the economics that are far more important. As I have explained many times previously the ultimate aim of Europe’s master plan, the fiscal compact, is to enact highly deflationary fiscal policy across the entire zone with the target of lowering government sector debt and deficits within a strict band. Although the focus is currently on high sovereign yields it is the stalling PMIs that are my major concern.

Coincidentally the Director of the Western Hemisphere for the IMF, Nicolás Eyzaguirre, is stepping down from his position and is soon to begin a new career running a Chilean television station. As a parting gift he has produced a very good overview of the driving thoughts behind the European master plan. I would suggest you read the entire post because I think it is very important for everyone to understand the motivations, but the crux of the analysis is:

Adjustment―the process of reducing government debt and deficits while restoring competitiveness―typically entails austerity and structural reforms. Austerity is needed to fit spending to the amount of available financing and bring down non-tradable prices to restore competitiveness, since currency devaluation is not an option.

A coordinated reduction of non-tradable prices including wages, agreed between labor unions and businesses, would be best, as it would mitigate the shrinkage in spending needed to realign non-tradable prices. But such agreements are often difficult to achieve.

Structural reforms typically include measures to facilitate the downward adjustment of non-traded goods prices. Reforms in labor and product markets achieve this by increasing flexibility and competition. But, if competitiveness is very weak, other reforms may be needed to spur comparative advantages in new sectors.

By their very nature, structural reforms take time to kick in and boost exports. In the meantime, if austerity is the only response to financial stress, the economy will experience a severe downturn or worse. As domestic spending shrinks, with the pull from exports still to occur, output will contract. Government revenue will also contract, feeding creditors’ fears of default and crimping financing.

In the private sector, contracting output will push down asset values, and affecting firms’ ability to borrow. Banks, typically overexposed to the non-tradable sector, will face sizable loan losses. If they respond, as is likely, through defensive deleveraging, this will exacerbate the contraction of private demand. In turn, deflationary pressures will increase the real value of debts, further adding to the malaise.

Eventually, the downturn would end as falling non-tradable prices make exports profitable again and boost import-competing home goods. But the output loss would be needlessly large. As structural reforms mature, the economy will once again become competitive, with the ensuing surge in exports boosting domestic demand and partially reviving the non-tradable sector. The trade surplus will allow the country to reduce foreign debt, and the recovery in tax collection will repair the balance sheet of the government, restoring access to market financing.

So there you have it, the end game for Europe and the basic idea behind providing external funding to nations during transition. Economic and fiscal reform followed by export driven recovery.

I just have one small concern. Spain, Germany, France, Italy and Portugal are all each other’s main export partners, so I have to ask exactly who is expected to take up the slack while these nations are attempting to internally deflate themselves against one another? As I said last week, surpluses somewhere require deficits somewhere else, so without an exceptionally large shift in the consumption patterns within Europe or the rest of the world this looks akin to pushing on a piece of string.

That’s not to say that it can’t work. If the ECB is willing to backstop the transition by continually sweeping up the mess created then there is a chance of success. But I do have to ask the question. Exactly how long is “eventually”, and will Europe’s citizens wait that long?

As I said before – Draghi delivered last week, but not where Mr. Market was expecting (it was impossible to deliver there). Germany does not want to be the one who gets blame for split Europe (yet, give it 10 years and situation may change).

Of course, that still won’t solve the fundamental problem, and I don’t see even recognition of what the causes are as opposed to trying to cure the symptoms..

Personally I believe that Draghi has just outmaneuvered Germany right out of the Eurozone.

And as for Delusion Economic’s commentary about the fallacy everyone trying to export their way to prosperity all at once… well, finance and monetary policy divorced themselves from reality long ago, so it’s no surprise that they’d divorce themselves from logic too.

Hay… what happens when everyone sends each other the bill?

Skippy… is it sorted by postal date or what, dine and dash?

Yes, to answer your headline. Draghi wants to inflate and Germany will have to follow slowly or the Western Fiat Ponzi is over.

The direction is clear, the path to be taken will be found. There will be more moments where the Germans have to say “yes/maybe” or the EZ will break. It will take the Germans many years to overcome this and then sunk costs will be even higher.

Besides, while I appreciate the diligence DE puts into his European analysis, I find his insistence on a possible “solution” of this crisis, well … delusional.

There are different ways to survive but energy constrictions, demographics, debt/ Keynesian endpoints do not allow a pleasant future for any country of the Western Hemisphere.

Umm… The Western Hemisphere is the Americas. Did you mean Northern Hemisphere, (though that too can’t be quite right)?

This is all so much crap and wishful thinking. The whole idea of the Eurocrats is one market independent of democratic politics. You get this by getting one country after another hopelessly in debt and then extending a helping hand and more importantly the conditionality finger. Germany has the most to gain from this, at least its bankers and industrialists do and these are the volk who matter. There will be lots of handwringing and scare tactics and idle threats, and before you know it the ECB will be buying Spanish and Italian and perhaps even Greek bonds and further enriching the speculators who loaded up on this drek while the faint hearted were desperate for an exit. Eurolabor is getting another shaft and I hope it feels adequately compensated by the possibility of migration at will from one capitalist Europaradise to another.

All seems to go according to the eurocrats’ script.

Yesterday, Mr. Monti appealed for governments to maintain “independence” from Parliaments.

Today, the leader of Germany’s SPD came out in support of “mutualisation of debts” (slang for eurobonds) under a condition of strict budgetary control for eurozone countries. Translation: some money for the periphery in exchange for more austerity. This is what passes for “the left” in Europe.

And Draghi may well get what he wants, because his is the only way for the austerian strategy to work without causing an unsustainable increase in the PIIGS’s costs of financing.

So, with Draghi calling the shots, governments insulated from parliaments and the left supporting the whole austerian strategy (with some demagogic calls for inane “taxes on the rich” to appease its electorate) the periphery will simply have to submit to more and more squeezes. It will be strangled in order to become “competitive” via more exports (at subsistence wages) as well as the violent contraction of imports that inevitably accompanies recessions.

Maybe the populations will react. But it’s hard to see how an effective opposition to these policies can be built when all the relevant political forces have internalized the austerian mindset. The situation seems to be evolving more or less in compliance to the eurocrats’ wishes – save for some unexpected turn of events.

The only sensible left in the continent of Europe is found in the political parties which are campaigning on a Eurozone exit.

All other parties that continue to believe in the ill-fated Eurozone are enabling the policies which are hurting the average worker.

Really, I don’t see much different here than a rehash of the last two years. The Troika has been trying to enforce “conditionality” in return for loans. The ECB was not allowed to buy sovereign debt directly, but they reduced collateral requirements to banks so the banks could buy crappy sovereign debt and flip it to the ECB for a three year loan. I guess one difference is if the ECB buys it outright, eventually they may be holding worthless bonds and at that point this debt is officially monetized, which is what gives the Germans some concern.

Then, when they fixed Greece the last time, the ECB and IMF made themselves senior to private bondholders and only the private bondholders got the 50% haircut. Then they were handed new long term bonds that had a 3.5% coupon. These were not too popular in the secondary market and last I heard private bondholders are sitting on a 80% loss, assuming they haven’t killed themselves. So now the private sector is a little queasy about putting the nest egg in Spain or Italy, and that’s why Europe needs the ESM. Last I heard they had trouble getting anyone – gov or private – to put money in that either.

So we are back to “if we just had growth, that could fix everything…”.

Germany/Chancellor Merkel is waiting for the U.S. elections to end this slow and anticipated dissolution of the Eurozone; she gave her word to bad Barry that she will not ruin his re-election chances and in return he gave her the Medal of Freedom (I don’t remeber which medal, but it was one of the highest honors). That is why it is taking so long. Of course, the German Supreme Court could get in the way, but that is unlikely because the SPD and Greens would be against it. The court will probably punt in some way, form or shape.

The horrible part is that internal devaluation will only prolong the misery and not accomplish anything. Internal growth can only come from investment: the markets however have no reason to invest in a declining demand scenario. And, I don’t see the Portugese, the Spanish, the Greeks, etc. coming up with a new cancer cure or a revolutionary energy saving device. They just have created an intellectual infrastructue to nurture scientific innovation that is necessary for autonomous growth.

Down with the Euro: it only helps the banks’ derivative profits.

“mean that much more of what is national sovereignty is going to be exercised at supranational level”

Means: less democracy.

Certainly it is just a coincidence that Mr Monti, the Goldman Sachs apparatchik who, unelectedly, reigns Italy, just said

“If governments allow themselves to be entirely bound to the decisions of their parliament, without protecting their own freedom to act, a break up of Europe would be a more probable outcome than deeper integration.”

So, apparently, he is not much in favour of democracy. But then, as Goldman Sachs Manager and EU Commissar, he wasn’t elected as well. And so he is only used to give orders, not to explain and campaign for what he wants to do.

Lesson learned: never make a Goldman Sachs guy head of state, or of institutions like the ECB. Oh, wait, the ECB is already headed by a Goldmann Sachsie….

No, Draghi does not favor democracy. And neither does any progressive who supports the Eurozone, as its only path to viablity is through democratic repression.

One decade ago, who would have thought that the UK, through its decision to preserve democracy by remaining outside of the Eurozone, would become the engine of the continent of Europe.

I was with you until your absurd last sentence. The UK is an economic and fiscal disaster. It’s economy is worse than Spain. Moreover, it has marginalized itself in European politics. How excatly is it the “engine of the continent of Europe”? By the way, you don’t seem aware that the UK is actually not on the European continent.

I have this image of two sockpuppets, one Draghi, the other the Bundesbank. It is not about one of them outmaneuvering the other but rather the 1% who are controlling both outmaneuvering ordinary Europeans in both the North and the South.

Bond buying will not fix what is broken in Europe. It is not meant to. Its purpose is to keep the looting going for as long as possible. That is all. Whether Draghi or the Bundesbank wins, ordinary Europeans will lose.

“since currency devaluation is not an option.” ; says who and why do they say that?