By Dan Kervick, who does research in decision theory and analytic metaphysics. Cross posted from New Economic Perspectives

The establishment’s debt and deficit hawks have taken flight once again, this time to launch a counterassault against Paul Krugman’s sensible and increasingly successful campaign to get people to stop clutching their pearls over the federal budget situation, and to focus attention on more pressing matters of high unemployment and economic stagnation. Joe Scarborough, Ezra Klein and the Washington Post editorial board are among those springing into action on behalf of deficit worry, and against the dangerous movement of calmness and sobriety breaking out all over. One thing that becomes more apparent as this debate unfolds is that the budget warriors frequently confuse broader public policy challenges that happen to have a budgetary component with narrower problems related to size of the budget deficit itself. A recent Atlantic piece by Alan Blinder unfortunately contributes to that confusion.

There is no secret about the fact that there are a lot of people who wish to shift many of the responsibilities that are currently borne by the federal government to the private sector. Others wish either to maintain the federal government’s responsibilities as they are, or else increase the government’s responsibilities. These are important debates. What they hang on are questions about whether the private sector or the public sector is more effective in delivering certain kinds of goods and services.

What these debates don’t hang on, or shouldn’t hang on, is the current size of the federal deficit or debt. How we manage the financing of our federal government’s spending commitments, given the choices we have made about what those commitments ought to be, is separate from questions about whether the government should or should not be taking on those commitments in the first place. It is true that there might be certain goals that we would like to achieve but that our society just can’t afford to pursue because of limits on our real resources. But the government is an agent of the society as a whole, so there is no meaningful sense in which the government can’t afford to do something that the society can afford to do. If there is something that we can achieve as a society and that we have decided is the proper job of government, then we can always financially empower the government to carry out our wishes.

Consider the case of health care. Many people claim that we are facing a social crisis over the long-term path of our health care expenditures. But if there is indeed a crisis over our society’s total projected long-run health care obligations, then we need to label it as such. It’s not a deficit problem, or a public debt problem, and pretending it can be addressed by “fixing the debt” or reducing the government’s deficit is, at best, simply an irresponsible punt. At worst, it is a dishonest attempt to exploit public fear and confusion over budgetary matters in order to push Americans into accepting a less prosperous and more unequal society in which the wealthy continue to detach themselves from the rest of the country and its shared commitments, and force the less affluent to accept a lower overall level and quality of health care.

Consider this analogy: Suppose there is a dam outside your city that is owned and operated by that city and its government. The dam is essential for flood prevention, electricity generation and providing the city with its water supply. But it is in bad repair and crumbling, and every year the city’s emergency dam maintenance expenditures have been going up. Ultimately, the city will either have to spend a lot of money in a short period of time to repair the dam for good, or else accept mounting annual maintenance costs that over the long run will cost much more than the one-time repair. Now suppose a city councilman rises to speak, “We have to do something about this dam problem! We must reduce our long-term dam maintenance budget!” I think it would be obvious to people that reducing the maintenance budget alone has nothing to do with addressing the problem. Deciding not to spend money to address a growing problem is not the same thing as fixing that problem.

It is possible that our pseudo-responsible councilman might also recommend selling the dam to a private sector firm, letting that firm provide the city with its electricity, water and flood prevention services, while also carrying out any needed maintenance. But here again we should note that you also don’t fix the crumbling dam problem simply by selling the dam to a private utility company which will then take on responsibility for those burdens, and tack the dam maintenance costs onto everybody’s water and electricity bill. The people of the city will pay either way. Maybe it makes sense to sell the dam; maybe it doesn’t. But there is no argument to be made for privatizing the dam based just on pointing out that the cost of maintaining the dam will shift from the public’s tax bills, payable to the city, to their water bills payable to a private company.

So it’s just totally dishonest to say about any problem, “We have to reduce the public commitment, because the government will never be able to afford this”, while saying with the same breath that the whole society will be able to afford it. If the society can afford it, then obviously the government can afford it since the government is just an agent of the society. The separate debate about public provision vs. private provision is a debate about delivery mechanisms, not about budgets and affordability.

The same moral should be drawn when we shift the discussion from dams to health care. Suppose under current projections our society will spend $X on health care in 2025, of which $Y is projected to be spent by the federal government, and $(X-Y) by private sector accounts. Suppose we then reduce our long-term deficit by reducing the 2025 public health care commitment to $Z, where Z is some amount that is less than Y. So far that that means only that the expected private commitment goes up to $(X-Z), and the private sector is now on the hook for the difference between $Y and $Z. Either way the society’s total commitment remains $X.

If there is indeed a long run health care spending crisis for our society, there are only two ways of addressing the crisis, and they both require policies that address our society’s total health care expenditures, public and private combined:

a. Reduce the cost of health care delivery over time via efficiencies and productivity increases, so we get the same health care bang for the same amount of real expenditure.

b. Reduce the overall amount of health care that is delivered over time per capita, so that the amount actually delivered in 2025 is less than what is currently projected.

Of course, we will probably employ a combination of both strategies. But whatever we do, we can see that the name of the game is to address the total social cost of health care. The question of what roles should be played by the public sector and private sector respectively, and what happens to public and private health care budgets as a result, is a separate further question.

The approach I favor, and that has long been favored by many other progressives, is to rely more on the public sector as a purchaser of health care, to leverage the public’s purchasing power in an organized way power to drive down waste and demand efficiency in the health care sector, and thereby reduce the amount of the total expenditure drained off of by extravagant and unnecessary profit-taking and rent-seeking. We can have more efficient, better quality and more equally distributed health care at a lower overall social cost if we get serious about using the latent monopsony power of the American people as a unified bloc of consumers of health care.

Alan Blinder recently addressed the issue of long term health care spending in a piece in the Atlantic. But he does so obliquely, and unfortunately his deficit-focused discussion seems to be a classic case of the “councilman’s punt” that I discussed earlier. Blinder tries to address the issue of the role of health care spending on the federal budget in isolation from the larger question of the total social cost of health care and the best means of providing that health care. And he bases his case for reduced federal commitment on arbitrary numbers and budget targets with no discernable independent public policy motivation. The result is a very unconvincing case.

Blinder begins by saying that we have a “truly horrendous” long-term budget problem attributable to health care:

The truly horrendous budget problems come in the 2020s, 2030s, and beyond. But while the long-run budget problem is vastly larger, it is also far simpler, for two reasons. The first is that the projected deficits are so huge that filling most of the hole with higher revenue is simply out of the question. Spending cuts must bear most of the burden. The second is that there is only one overwhelmingly important factor pushing federal spending up and up and up: rising health care costs.

He then adds:

Any serious long-run deficit-reduction plan must concentrate on health care cost containment. Simpson and Bowles knew this, of course. But they didn’t know how to “bend the cost curve” sufficiently. Neither does anyone else. So they just recommended a target–holding the growth rate of health care spending to GDP growth plus 1 percent. In short, Simpson and Bowles, brave as they were, punted on the most critical issue.

But as we have seen, this is a blinkered approach to the health care problem. If public expenditures are projected to grow as a result of increasing social health care costs, it makes no sense to address this problem simply by reducing the planned public side of the expenditures – as though the government’s obligations stop at the border drawn by its current budget, and as though health care spending outside the federal budget is someone else’s problem. The government is not just some kind of big human resources department that might decide, due to anticipated revenue decreases, to cut back on the dental benefits it provides its employees, and let the employees pick up the cost of cleanings and fillings themselves. The government’s role is to consider the public good in a holistic fashion, and decide on the best mechanisms for pursuing that good. And a national government’s options for commanding and organizing the resources the country has available to meet its social challenges are much less limited than the private company’s options. The company can’t just decide to lay control to a larger portion of society’s resources, without increasing its sales, in order to provide its employees with expanded dental coverage. A government has no such sales constraint on its revenues, and its power to claim resources and organize their use for public purpose is far broader. So the only question then is whether it makes more sense for the public sector or private sector to carry out the kinds of health care expenditures in question.

An obvious response to Blinder here is to say that if the volume of health care expenditures is projected to increase, and it makes sense for the public to carry out those expenditures through such programs as Medicare, or an expanded and progressive single payer system, then the government will simply have to increase its tax revenues. If the public wants to spend a certain amount on health care, and they want the government to organize the disbursements, then they need to turn over some appropriate amount of revenue to the government. But Blinder says that addressing the public health care commitment problem can’t come simply from more taxes, or even equal amounts of tax increases and federal budget cuts, but must come from “mostly cuts.” This position is illogical. If the private sector can cough up some quantity $X in additional spending to pick up the health care spending slack caused by reduced government commitment to health care, then it can surely come up with $X in additional tax payments to fund an the same amount of spending through the public treasury. Cutting the federal health care budget is not the same things as cutting the amount our society spends on health care.

So why does Blinder think the only solution is cuts? He puts forward an arbitrary criterion for thinking about public policy decisions and revenues – an 18.5% rule. After considering the possibility that US government revenues might rise to a larger share of GDP, Blinder says this:

There are four takeaways. One: The interest bill–which is the vertical gap between primary spending and total spending–eventually comes to dominate the budget. Two: Historically normal levels of taxation (the bottom line) do not come close to covering even primary spending (the middle line), not to mention interest payments. Three: Primary spending as a share of GDP rises steadily, from 22 percent of GDP now to over 32 percent by the 2080s. Four: The government can cover no more than a small fraction of the projected deficits by raising taxes. Sorry, Democrats, but the Republicans are right on this one. Americans are used to federal taxes running about 18.5 percent of GDP; they will not allow them to rise to 32 percent of GDP. Never mind that a number of European countries do so; we won’t.

This is a rather imperious and groundless statement, issued on behalf of all Americans, about what they will and won’t allow, and might or might not choose to do in the future. Whether Americans are willing to pay more for a given government service surely depends on what they conclude about the quality of that service, and about whether entrusting it to government saves money for them elsewhere. I wonder what Americans would think if they were told their tax bill was going up, but all of their out of pocket health and dental care expenses were going to disappear.

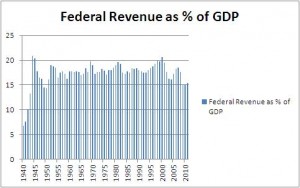

Blinder bases his case for the 18.5% rule on the historical record of federal tax revenues as a percentage of GDP:

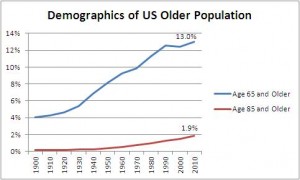

In fact, federal revenues have exceeded 18.5% a few times. But that’s not what is really important here. Here is another historical record, the percentages of the population over the ages of 65 and 85 respectively:

Should we say that since the over-65 population of the US has never been greater than 13%, then Americans “will not allow” that percentage to ever grow higher? Of course not. One can’t simply look at a path of percentages over time and declare that the maximum previous numbers are the cap beyond which the public will never permit a large number. That’s not scientific public policy thinking. It’s numerology.

There are also some options for public financing of health care that Blinder doesn’t consider. If revenues as a share of GDP don’t increase, but government spending as a share of GDP – driven by health care – does increase, then on the mainstream picture the difference will have to come from public borrowing, and as a result the interest payments on the public debt will grow. Depending on the volume of the growth, that might create a long-run sustainability problem, as Blinder notes. But for monetarily sovereign governments like the United States, the option always exists of spending in excess of the total amount borrowed or collected in taxes. In other words, the government can engage in functional finance. While MMTers have long endorsed functional finance and have studied its ramifications, an increasing number of mainstream figures are beginning to engage with the functional finance option, including Adair Turner and Martin Wolf.

But both mainstreamers and MMTers recognize that if there are substantial increases in the size of the federal budget as a share of GDP over time, then taxes will likely have to go up to cover at least part of that increase. Taxes are a tool for shifting resources from private control to public control. The conventional picture is that the money that is taxed comes from some mysterious private sector source, and must first be captured from the private sector by the government so that it can then used to purchase goods and services. The MMT view is that the government provides the money to the private sector in the first instance and then taxes it back to give the currency value and sustain the demand for the currency. At full economic capacity, the government also increases taxes so that it can increase its own contribution to the aggregate demand for goods and services without enabling dangerously inflationary private sector competition for those goods and services beyond what the society is capable of producing. Either way, taxes are part of the process by which the government provisions itself with resources and procures services from the private sector. So if there is an increased public responsibility for the provision of some kind of good, there will generally be at least somewhat more taxation.

Where Blinder goes wrong is in declaring an arbitrary cap of federal revenues as a share of GDP somewhere in the vicinity of 18.5%. This idea that there is a permanent limit on the size of government baked into the budgetary DNA of the American republic is without warrant. Progressives should continue to press forward aggressively with calls to boost the public responsibility for health care without worrying that they will exceed Alan Blinder’s budgetary speed limit.

I see a problem with all of this analysis. It ignores one fundamental question.

If you are talking about the dam, selling the dam to some private company means that costs will be assessed according to who uses the water. At first glance, that may seem fair, but there are a number of people who benefit from the availablility of water who are not paying by the glassful.

If the city maintains the dam, the costs are distributed (net necessarily evenly) according to the tax structure of the city. This may mean that business is assessed a greater share of the costs. If you add in state and federal matching payments, it becomes harder and harder to understand where the money is coming from.

When it’s time to make a decision, the question of who pays is made in back rooms and camoflauged by analysis that answers every question except “who pays the bii?”

You obviously didn’t read Kervick’s as he specifically dismissed the importance of weather the dam should remain in the hands of the city or sold off. Either way the dam needs a huge infusion of spending to counter its advancing decay and or repairs needed to restore the dam. The damage done to the dam remains the same regardless of who controls it.

What Kervick is pointing out is that selling the damn, doesn’t magically fix the damn. All it dose is shift the burden of its repair and maintenance to another entity.

I actually did read the article, and I was aware that Kervick was saying that selling the dam does not fix the dam. That seemed to be a statement of the blatantly obvious.

I asssume that not fixing the damn is not one of the acceptable choices.

The part that seems to have been left out was the important part — who actually pays for fixing the dam?

You can juggle the numbers and play politics with the city budget. The city fathers might like to pretend that selling the damn is a better deal because it makes the rest of their budget look better.

To me, as a resident of Mythical City, USA, the important part is who pays the bill.

It’s the lack of any real analysis that explains why the residents of Chicago have sold all of their parking meter revenues to some rentier corporation. And if they block a street for street repair, they have to compensate that corporation for the lost meter revenue.

You said “All it does is shift the burden of its repair and maintenance to another entity”. That is not quite a true statement. It pretends to shift the burden to another entity. In reality the cost of repair and maintenance is shifted from one set of taxpayers to another set of taxpayers.

It’s similar to the process where the income is transferred to the 1% and the expenses are shared by everyone else.

If you don’t ask the right questions, your analysis is pretty much worthless.

Dude, you just said exactly the same thing as Kervick. Society pays, always (that’s you and me Gerard), whether through taxes or through higher prices: that is the whole point of his example with the dam.

Do they?

Be it fees or taxes, the consumer can pay nothing without first being given a sufficient wage. The same is true for corporations; they can not spend a dime without first financing that expense in some way. All money ultimately comes from the fiat state, and the fiat state must spend that money into existence.

So by your reasoning, the cost of fixing the dam doesn’t fall on the people, but the state.

I love the whole damn dam analogy!

You’re right that I did disregard those questions Gerard, although you can tell from the single payer approach I support where my sympathies lie when it comes questions of the equal distribution of health care.

My focus in this particular piece was just on the the deficit hawk fallacy I called the “councilman’s punt”. No matter what people think about the public vs. private question in health care, there is no good argument for privatization based only on the fact that the deficit is a certain size. If there is a good argument for public health care, then we should put together the public financing mechanisms we need to provide it. If, on the other hand, someone thinks health care should be private because they believe in the virtues of the market system, then they should argue for that directly.

But Blinder’s whole argument for reducing the public commitment to health care has nothing to do with the virtues of privatization. He just thinks there has to be some sort of cap, somewhere in the vicinity of 18.5% of GDP, on the total size of federal spending. My claim is that the government should do all of the things that work best if the government does them, and there is no a priori percentage of GDP you can point to that says where that public/private line falls.

And of course, the councilman’s punt is used over and over by budget warriors, not just in the area of health care, but for shrinking the government in many other ways as well. This has been a key tactic of the neoliberal privatizers in the US and Europe: try to convince the part of the public that is otherwise positively disposed toward public provision of certain goods that we “can’t afford them”, because deficits are too big.

Thanks for the acknowledgment. And I do recognize that we are mostly on the same side of the issues – especially in regard to health care.

Conservatives are still basing their arguments on a day when honest private businesses could perform a service more cheaply than incompetent government organizations.

Those days are gone forever – along with the honest private businesses. Today’s predatory corporations are unable to deliver economic services and meet the expectations of our financial system.

Blinder’s argument self destructs when you apply it to activities that have to be done. The bottom line is still who pays the bill. If you have a cap on the total size of federal spending, either the states or private individuals have to make up the difference.

If the dam bursts or medical care becomes unavailable, some people are going to die.

There are lots of things the private sector has never been able to do well. And if you rely on markets to provide some good, then even if those markets perform efficiently and according to theory, you still get a standard market outcome: some people get lots of the good, and the highest-quality versions of it; some people get little of the good and the lowest quality versions of it; and there are lots of variations in between. If that’s not the kind of society we want to live in where health care is concerned, then we can’t rely on markets to handle the job.

Gerard Pierce: “Conservatives are still basing their arguments on a day when honest private businesses could perform a service more cheaply than incompetent government organizations.”

I am not sure that I have ever known such a day. These days, it seems that our choices lie between govt’ bureaucracies and corporate bureaucracies. IMX, the gov’t bureaucracies win hands down, at least in the U. S.

I’ll let the the free market decide whether or not I get to have a yacht. I don’t want it deciding whether or not my kid gets to go to the doctor.

Dan,

What should or should not be provided by govt is a good topic for debate. But I wish you would also be realistic or honest about the cost-effectiveness of the govt solution…..they are rarely, if ever, the source of cost-effective outcomes as a simple byproduct of who and what they are…..they are elected and incented to play santa claus without end in order to stay in office. If the greater incentive rests with playing santa claus and the lesser incentive rests with being efficient or effective…we will get santa claus, pure and simple. Let’s take univeral healthcare as an example……

Universal healthcare is a worthy goal to aspire to….few would argue and I agree as well. So what did our govt come up with? Another suboptimal solution. Health insurance is the business of actuarially determining the probability of a claim and then pricing it accordingly. If we provide healthcare to everybody, there is no longer the need for healthcare insurance….and were it eliminated by the way, it would go a long way towards covering the cost of the healthcare for those currently without it. But nnnnnnoooooooooo……..that would upset too many insurance industry voters. So govt comes up with a solution that protects this now unneccesary layer of cost and we end up with a system that will cost more than it should, despite claims to the contrary by our govt architects…..this is nothing more than an insurance industry windfall….. stuffing 30 million more clients through the existing system, and highly inflationary, again, contrary to govt architect BS. When cars made horse and buggy obsolete we didn’t artifically keep buggy makers supported, when trucks made trains obsolete we didn’t artifically keep the train industry supported, etcetc…..obsolete industries and their employees had to find other work…..that is capitalism, and it works when our conflicted central planners allow it to. But no more……..we now have obsolete and excess capacity industries artifically supported in health insurance, cars, banking and perhaps others…..all in the name of vote grabbing in what has become handout, bailout, law-breaking-is-acceptable-for-the-connected nation.

It is risky, even dangerous to lull people to sleep about our govt’s ability to run up deficits to support whichever industries they want to intervene in for legitimate, or more likely, vote-grab, purposes. Only the fed’s soaking up of 90% of treasury issuance in the 10 yr and higher maturities allows us to even be having this conversation. I know you also participate in Cullen’s website, and I believe in his explanation of our monetary system……where I disagree is in his wish to portray, naive in my view, the fed’s behavior as NOT monetization simply because a middle man primary dealer takes possession of the issuance for as little as a few hours or days. The fed’s conduct is, at best, buying us some time to get our house in order…..it should not be used by others, and now you seem to be accepting, as a long term way of doing business. Respecfully, krb

well given that we weren’t going to be able to have a public option then allowing insurers in was the only option.

but Medicare is actually cheaper than private insurers. as is the VA. they may have their problems too, but then so does private insurers

krb: “But I wish you would also be realistic or honest about the cost-effectiveness of the govt solution…..they are rarely, if ever, the source of cost-effective outcomes”

Good point. OTOH, for much of the private sector, cost effectiveness means screwing the consumer. Especially in the FIRE sector.

Great post as always here.

I love the dam hypothetical. Except you forget the part where “private” corporation’s management (who do not live anywhere near the valley) does a shoddy job repairing the damn while paying themselves large bonuses. (Freedom!). Then the dam fails and thanks to its limited liability the company merely goes bankrupt (or even gets bailed out by the government) meanwhile leaving the government to repair the damage.

Voila! Control fraud and externalities. What is absolutely wrong with our corporate system in a nutshell.

Yep. The dam is probably TBTC (too big to collapse), so some of the cost of repairing when it looks like it’s about to give way will end up being socialized anyway.

When that happens, whatever happens with the people in the valley when the water is three feet high and risin’, you can be sure the owners will all be high and dry.

A number of infrastructure “investment” groups seem to have this as their business model: buy former government-run infrastructure, partially asset-strip it, then get the government to agree to let the captive customers be rack-rented to raise money for maintenance, because the infrastructure cannot be allowed to fail.

This is why the use of CBO estimates as a club against single payer advocates by ObamaCare advocates was so dishonest. Single payer would eliminate about $400 billion dollars a year in administrative overhead, profit, and executive salaries and bonuses — enough to instantly care for all the uninsured, if we chose to.

However, the $400 billion savings accrues to society as a whole, and so doesn’t show up in the CBO estimates at all, allowing Obama’s shills to argue that it was more expensive.

“…Single payer would eliminate about $400 billion dollars a year in administrative overhead, profit, and executive salaries and bonuses…” – Lambert

That $400 billion is often stated as 30% of premiums paid to private health insurance companies by employees and employers. The way I’ve been looking at it, we could expand Medicare by paying 70% of current premiums into FICA. If it could work that way, the savings would be obvious to anybody who gets a paycheck. Could it be that simple?

Lambert:

Keeping the hybrid system we have will ensure costs increase far in excess of inflation. Hence Obamacare institutionalizes the hybrid system.

Very well written article by Kervick. I like that he used the dam as his analogy because there is an unspoken consequence of not figuring out what to do: we all drown.

“with a sovereign govt like the U.S. we always have the option of spending in excess of the total amount borrowed or collected in taxes”

I see this argument made often enough as a justification for having the fed gov assume the burden of whatever somebody’s favored project is at the moment(in this case health care). Its an attractive argument because its logically correct.

Too bad it is just wishful thinking. Can anyone say when the last time this occurred in the U.S.?

Before piling more obligaqtions on us sheeple to pay interest to the new nobility, progressives may want to figure out how to make Kervick’s comment about spending a reality.

If you count the Federal Reserve as part of the US government, then we are, in fact, spending more than we tax and borrow through QE. The only difference between what the Fed is doing and what Dan suggests is that right now the money creation is only being used for the benefit of the banks. “MMT for me, but not for thee” seems to be Wall Street’s mantra, as of late.

From what I’ve seen and read, MMT folks seem to accept the Fed as a government agency — but it’s NOT. It is owned by the member banks, who in turn, if they do not own the federal government, are giving a pretty damned good impression of it.

While the Fed is partly private (or mostly, depending on who you ask), I would argue that its monetary operations should be seen as government actions, since its monetary authority derives from the Constitution via congressional mandate. It might best be viewed as a private entity acting on behalf of the government. Government is the ultimate power supporting them, however, and what Congress hath given, Congress can also take away (at least theoretically).

The Fed describes itself as “independent within the government.”

One way or another, when the G-20 gets together to run the world, the central bankers are there at the table along with the finance ministers.

http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/world/la-fg-g20-meeting-20130217,0,2819204.story

On Market Mongo we have a social safety net we call “The Disability of Surviving Old Age” . It is very similar to your airline frequent flyer programs. Mongopoly, Inc. Airlines awards frequent flyer miles to resident flyers during their working careers and then as senior residents they can use them to get transport to the destination of Mongopoly, Inc. Airlines’ choice and free peanuts along the way.

No one on Market Mongo has retired yet, but the Emperors’ Auditors assure the Emperor that everything will be OK.

The healthcare issue was more complex. Initially, Market Mongo economists recommended eliminating healthcare as being the optimal choice. They noted that residents didn’t accumulate photon credits quickly enough to afford purchase of items in the Mongopoly, Inc. Online Catalog and the Heathcare Products and Services division was therefore a drag on the overall profitability of Mongopoly, Inc.

Top management at Mongopoly, Inc. studied the creation of a healthcare insurance division, but quickly concluded that could only make the problem worse. Two underperforming business units.

Finally, the decision was made to shut down the healthcare division and transport those employees to Mongo Commons.

Here is where your Emperor gets chastised for unintended consequences, not to mention listening to economic advisors. Data collected by the personal department of Mongopoly, Inc. indicated a much higher and rising incidence of workers dropping dead both at and away from work. When Mongolian Black Flu broke out and ran thru the workforce unchecked, Mongo GDP fell 27%. Quite unacceptable performance we all agreed. Something had to be done.

So we contacted all the former employees of Healthcare Division that we could find in Mongo Commons and offered them their jobs back at half pay. They also agreed to stop making silly drugs and healthcare equipment that didn’t do anything except cost money. They agreed to sell the remaining pharma product at a standard cost of 10 photons per pill, which was what cost is anyway.

Results have improved, and we think the crisis is behind us.

Some of this is quite close to my resource/social purpose theory. We begin at the level of what kind of a society we its members want. We take stock of our resources: people, skills, infrastructure, raw and finished materials. We use government through its power to spend, tax, legislate, and regulate to effect and monitor the necessary distributions to accomplish the social purposes we have established. Finally, we use money as the medium of distribution, the score card if you will, giving access to our society’s resources in order to fulfill our social purposes.

Note that in this model social purpose permeates the system at every level. This is important because what makes our modern kleptocracy so successful is its scission of money and wealth from any social purpose.

A criticism I have made in the past is that MMT with its origins as a monetary theory begins at the end of this process, and its efforts to work backwards toward a set of first principles leaves it open to all kinds of justified attacks. If you work down the intellectual chain as I do there is a natural intellectual flow to the ideas and the social purpose of the enterprise is never lost. Working back up the intellectual chain is a lot dicier because there is no one and only one set of principles to which a lower step leads. This is why for example many of us have pointed out that MMT’s view of fiat money works equally well for a kleptocracy and looting as it does for a social purpose model. If you start with social purpose, what we want our society to be, however, kleptocracy is never an option. It is precluded at the outset and at every step in the process by the social purpose with which the process is embued.

What does this mean in so many words? We should never look at money without remembering what its social purpose, to build the society we want. Any distribution of wealth should be measured against how well it serves creating that society. And if we are smart in our choices, then one of the primary aspects of that society is that it delivers a decent and worthwhile life to each of us. If we choose this, there is no threat to redistribution of wealth to accomplish our goals. No one is deprived of the wherewithal for a good and decent life. The point of redistribution is in fact the opposite. Resources are redistributed to make sure everyone has what they need for such a life.

Redistribution occurs now. The difference is that its aim in kleptocracy is to strip we the many of what we need for a decent life in order that a very few may control not only the resources they need for a good life but everyone else’s resources as well. From a social purpose standpoint, this is insane. It is criminal. It is not what any of us, the many, signed up for, and, most importantly, it is not something we have to stand for. There are other, better ways.

We begin at the level of what kind of a society we its members want.

The left never, ever discusses this.

You are right Hugh That’s the one thing I kept stumbling over when I thought MMT was a great theory, but I couldn’t think through it using our current social paradigm. And I always came to the same dead end – sort of where Japan is as we speak. That we would work our fingers to the bone trying to export stuff. And the profit takers would be as fat as ever. Kervick does a great job here of explaining how it should work. Because either way we-the-government provide the money to the private sector in the first place. Also, this is the first time I have noticed the term “functional finance” which I think is very descriptive too. It’s too bad this article isn’t published by the Atlantic as a counterpoint to what Blinder just did. More people should be reading Dan Kervick. He has a knack for explaining things.

Thanks Susan. The term “functional finance” was coined – as far as I’m aware by the economist Abba Lerner. Here is the paper in which he introduced the term:

http://cas.umkc.edu/economics/people/facultyPages/wray/courses/Econ%20601/readings/lerner%20functional%20finance.pdf

I discussed functional finance and Lerner in an earlier piece: “Paying for Lunch – MMT Style”

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2012/12/paying-for-lunch-mmt-style.html#more-3892

Hugh,

Your model sounds like sweetness and light. It needs to take particular account of three constituencies: (1) the Something-for-nothing brigade; (2) the Something-for-trickery brigade; (3) the most problematic of all: the Something-for-violence brigade. I come from a land of thousand year old castles, where the Violence brigade did very well for 600 years, until the Trickery brigade took over, which is where we still are today.

(Note: the Violence didn’t go away. It was just subsumed under the service of the Trickery).

I did not mean to suggest that this would be easy or not demand a lot of hard work, struggle, sacrifice, and commitment, just that it is doable and worthwhile doing: building a society that works for all of us, and not just a few.

Is this the Alan Blinder who emailed me that Obama’s only mistake was not explaining his programs clearly enough?

This is the Alan Blinder of Blinder and Blinder Economic Consulting, right?

Almost certainly this Alan Blinder is Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton, former Vice Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, and frequent columnist at the Wall Street Journal. http://www.princeton.edu/~blinder/

Before I reached the point where I couldn’t stand it anymore, I perused the editorial pages of the Wall Street Journal, looking for signs of light. I enjoyed Blinder’s contributions as a relative voice of reason, against the mind-numbing ideological claptrap spewed by the WSJ editorial board.

I’m not defending Blinder’s 18.5% barrier. My hunch is that rather than mount a vigorous defense against Dan’s argument, Professor Blinder would concede the point, perhaps offering the usual disclaimer of the prospectus, that past peformance will not necessarily be a reliable predictor of future results.

My sense is that Blinder is among those economists at elite institutions who instinctively reach for some ideal of the moderate center, and are always seeking to define that center. They feel that economics is a post-ideological, morally neutral instrumental science, and that economists should practice a sort of lordly neutrality, to protect the integrity of their advice from accusations of partisanship or moral zeal. Since Blinder had taken the left-tilting anti-austerity side on the debate about short-term budget policy, he felt he had to balance his position by taking a more hawkish and right-tilting line on long-term budget policy.

This kind of stuff seems to go on incessantly among economists. It’s never just a matter theory, evidence and moral goals. They are always involved in some kind of negotiation with a circle of elite peers, in which they try to push and influence the conventional wisdom while re-establishing a new consensus, through tit-for-tat gestures.

Paul Krugman ran an odd piece a few weeks ago in which he expressed exasperation over the fact that he thought “saltwater” economists has been negotiating in good faith, so to speak, but the “freshwater” economists in Chicago had not reciprocated appropriately. It was a telling piece in that it was surprisingly frank in its revelation that intellectual constructions like the so-called New Consensus are not put together through a scientific process based primarily on the assessment of evidence and intellectual honesty. They are more like theologies or creeds assembled by modern day economic Councils of Nicea for the benefit of the faithful in the general public and the political class, and which the episcopal elite then agrees to get behind for the good of the Church.

I’m reminded of Joe Firestone’s “small ball” and “game changer” metaphor. The academic elites and prominent pundits have been playing “small ball”, addressing each other in their circle of peers, steering well clear of suggesting new game-changing paradigms. One must read NC to find game-changing discussions, and to help shed the neoliberal conventions that have been drilled into our minds, practically since birth.

One observer who stands out in my mind as offering game-changing commentary is William Greider, writing in The Nation at the peak of the GFC, late 2008 and into early 2009. Otherwise, with few exceptions, such as NC and NEP, most easily accessible commentary amounts to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic after the iceberg has been observed on the horizon.

This article will be my standard for some time to come. It offers an excellent framework within which to elaborate on several important points. This is one of those times when I wish certain articles on NC could be made “sticky”, to remain at the forefront for a long time, the better to wring out every last bit of vital commentary and discussion.

I really appreciate that citzendave.

I was just punning, hehehe. He should open a consulting firm with a family member, though, that would be great.

Possible marketing slogan: “When you hire us, you will be getting Blinder and Blinder.”

I believe my economic advisors get their newsletter, “Blinder and Blinder Economic Insights”.

ONE HELLUVA SACRED CASH-COW

It is intransigent of a nation to overlook a major problem that has existed for a great long time. Health Care is the bird that is coming home to roost, since we’ve always taken it for granted that it should be covered by privatized insurance.

Privatized, me arse. Health Care is not a business. It cannot be a business. With the obesity pandemic in full rage, we have more consumers seeking Health Care services than there are service providers. And it will always be that way. Meaning this: The service providers set the prices -higher and higher and higher.

Which is why, having noted this simple reason, which escapes the benighted Replicants in Congress, Europe long-ago nationalized Health Care. And, thus, today, have HealthCare costs that half as much, if not more, as that of the US. Have a look-see here.

What magic do the Europeans employ that we cannot seem to master? Easy question. They do not accept health-care costs concocted by the the local Medical Association in cohort with private insurance companies. They mandate the costs that can be applied by HC-practitioners.

Damn simple, n’est-ce pas?

Why can’t we do that in America? Because healthcare is a sacred cow? If so, that’s one helluva cash-cow that we have to feed.

Not only, when are going to understand that just because we have “insurance” that does not mean it costs us nothing? Company private HC-insurance is paid in two parts. A small part is paid for by the taxpayer – meaning, if you don’t get any, you pay for it anyway.

The larger part, however, companies impute as an Operational Overhead that they recuperate in the price. Meaning, once again, whether you have it or not, you pay for it as a consumer of products/services.

And because it is so damn expensive, the cost helps price our labor out of some foreign markets, meaning it actually costs us jobs.

MY POINT?

Dumb is a dumb does.

But this dumb is simply shooting ourselves in the foot – then calling for the ambulance to take us to see a doctor …

In short, as we function today America is not capable of solving problems. For the most part our government, especially at the federal level, now exists as a means of delivering money to the connected. Solutions to real problems that do not begin and end with this goal not only can’t be passed, they cannot even be considered or discussed. All those involved, eleceted oficials, lobbyists, media, etc., understand this, and act accordingly. It is not that aren’t solutions to our problems, it that they can’t be solved with the solutions the connected folks desire. Selling the dam is the only solution that makes any sense.

We do have damn problem.

The 18.5% “limit” might be completely arbitrary from a logical or ethical standpoint but we hardly live in a society where truth and/or justice prevail. The only limits that matter in the short run are those set by elites. Journalistic hacks aren’t just lazy/bad thinkers, they’re apostles to the prevailing relations of power. People like Blinder happily inhabit a world where the government requisitioning more than 18.5% of society’s resources to provide vital services to the population is a quaint absurdity.

The notion that a society can afford to repair, replace, fix all the body parts of all of its memebers is as absurd as it is disingenuous.

Health care must be about health, not illness. This is the only affordable/sustainable option.

AN OUNCE OF PREVENTION

Point well taken.

So, let’s start with the obesity pandemic that has overcome the US. Americans are eating themselves to a quicker death. Our life-span has already been reduced one year in a population where more than a third are obese and just less than two-thirds are now overweight.

I suggest a Public Option Healthcare System, which is, like today, public-, worker- and employer-funded. But no private insurance intermediary. The Dept. of Health (managing the Public Option) would mandate healthcare service pricing across the nation in a manner to assure both fair remuneration of practitioner wages and also incentive-payments for results and not just procedures. (GPs in the US already earn four times the median American wage.)

The worker-paid contribution to the Public Option would be made through deductions from their paycheck. But, all those insured under the Public Option would also have to pay a substantial annual fee that could be refunded upon one condition: Their waist–hip ratio and body fat percentage are within acceptable limits. (Or any other such yardstick that would be applied.)

Otherwise, the fee is retained until they do achieve the necessary limit. Obese individuals should be made to pay for their own personal negligence. Just like auto-insurance policy increases for those who habitually have accidents.

Regardless of the solution-type, something must be done to stop the pandemic that has reached outrageous proportions. (Not permitting food-stamp uses for junk-food would be one measure worth applying affect the prevalence of obesity amongst the poor.)

A people should not be allowed to be negligent of their personal healthcare then, when an illness inevitably arises, depend upon a public healthcare remedy to cure themselves.

Meaning we need to accent Preventive Healthcare measures as well as (and perhaps more so than) the needs for Remedial/Curative procedures.

An ounce of prevention is worth a ton of cure in healthcare.

Smart.

… or as some famous politician way out there in the wider world of wonder suggested … just let the old and infirm die sooner … a money saver extraordinaire

This piece is excellent.

OUTSIDE THE BOX

Perhaps but we are not thinking of the one option that really works. Healthcare is an oligopoly – where too many patients are constantly chasing after too few service practitioners.

Meaning the latter set the prices for the former … and our government simply tries to find additional avenues of revenue to fund an ever increasing percentage of the GDP.

Which is like the cat chasing its tale, which it never catches.

Europe had the good wisdom decades ago to see through this “game”. They nationalized Healthcare and mandated the service pricing mechanism. Thus, many European countries (similar demographically) spend 5-to-6% less than the US as a percentage of GDP. Countries like Australia and Italy spend half as much.

See the Infographic here

Six percent of $13T (GDP of the US econonmy) is around $780B. Think what we could do otherwise with that money. Particularly in education, where it is needed so badly.

It’s time we started thinking outside the puzzle box.