The debate around Obama’s proposed minimum wage increase (when he had promised to deliver an even bigger wage rise in his first term) focuses mainly around how much economic stimulus it will provide and whether it will simply lead employers to cut worker hours (given how obscene corporate profits are, most companies have plenty of room to pay their employees more, even if their kvetching would lead you to believe otherwise. Remember, companies used to share the benefits of productivity gains with workers; it was in the later 1990s they started keeping the upside all for themselves). But a look at that question reveals what low wage workers do when they get pay increases.

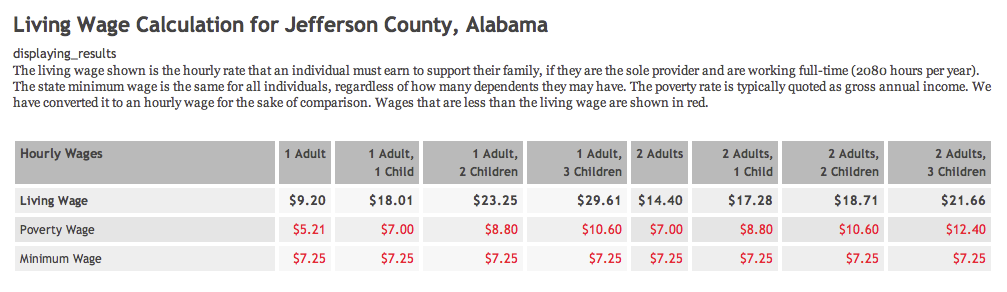

However, $9 an hour (which won’t be in place till the end of 2015 if Obama prevails) is still well below today’s living wage in most states. For instance, from the MIT site, Poverty in America (click to enlarge):

So even a single person can’t get by now on $9.20 an hour in Jefferson County (see MIT site for the breakdown of living expenses).

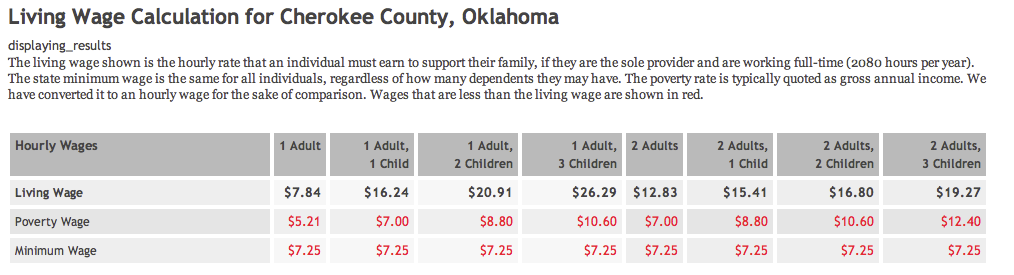

Well, if you go to Oklahoma, the ninth poorest state in the US, you might get by:

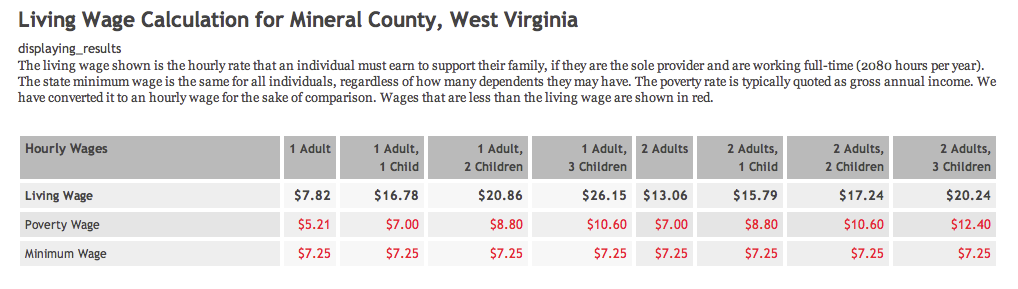

Or West Virginia, the second poorest state:

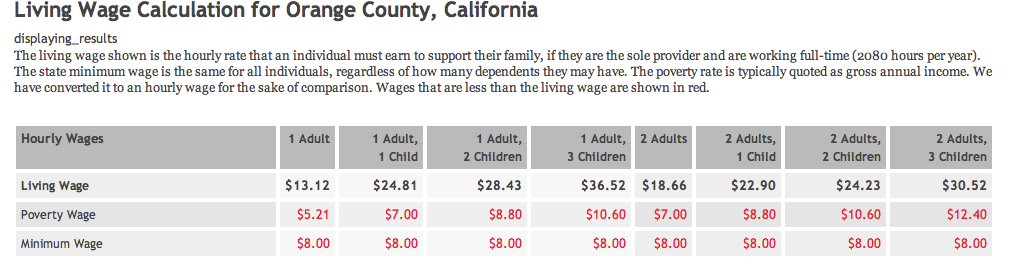

But not Orange County, California:

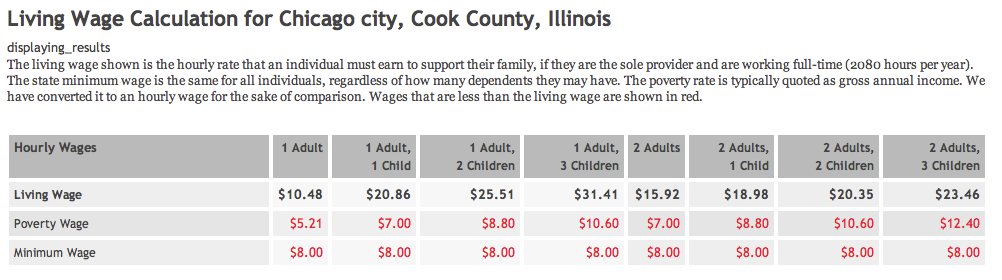

Or Chicago:

This is to give some context to what happens when minimum wage workers get wage increases. They go into debt. From a study by Daniel Aaronson and Eric French, both of whom work at the Chicago Fed, per VoxEU:

A central part of President Obama’s 2013 State of the Union address is a proposal to gradually raise the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $9 per hour. Proponents have argued that raising the minimum wage may provide fiscal stimulus by putting money in the hands of people who are likely to spend it (see The New York Times 2013). This argument is sometimes based on findings from our research (Aaronson, Agarwal and French 2012), where we estimate the spending, income, and debt responses to minimum-wage hikes, as well as calibrations presented by the Economic Policy Institute (Hall and Cooper 2012). In this article, we describe our results and discuss the implications for policy…..

Our data spans 1980-2008, a period where many states had minimum wages above the federal minimum. Indeed, today, 19 states plus the District of Columbia and several cities have a minimum wage above $7.25. Our estimated minimum-wage responses are identified by comparing a minimum-wage household residing in a state receiving a state-level minimum-wage hike to another minimum-wage household at the same time who resides in a state that did not receive a hike.

What they found was pay to the lowest wage workers rose but not the pay of the workers who were above the bottom strata, which is not surprising:

We use data from the outgoing rotation files of the Current Population Survey, the Survey of Income and Program Participation, and the Consumer Expenditure Survey to estimate the impact of a $1 increase in the minimum wage on household income. The weighted average income response to a $1 minimum-wage hike across all three datasets is roughly $250 per quarter for the first year. These results are limited solely to households with adult workers very close (60% to 120%) to the old minimum wage. Workers that are just above this threshold (e.g. 120% to 300% of the minimum wage) experience no statistically or economically significant increase in their income, even when they too reside in a state with a minimum-wage hike.

Since minimum wage employees work an average 300 hours a quarter, this makes sense so far. Now look what happens:

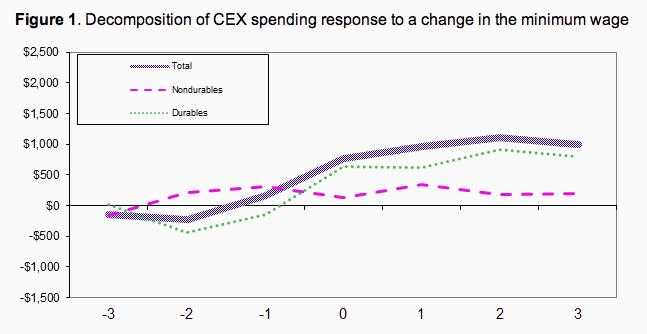

To estimate the spending response to a minimum-wage hike, we use data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey. In the year following a $1 minimum-wage hike, we find that spending rises, on average, approximately $700 per quarter for households with minimum-wage workers. As with the income responses, we find no spending response for households without minimum-wage workers, including households with adults paid just above the minimum wage. Virtually all the additional spending is on durable goods. Specifically, spending on new cars and trucks rises by $500 per quarter, of which the majority is debt-financed.

The authors stress that the borrowing is almost always collateralized, with car loans the biggest component of the increase:

Using the same estimation procedures for income and spending, we find that auto loan debt rises by $200 per quarter and the sum of auto, home equity, and credit-card debt rises by $440 per quarter following the minimum-wage hike. Figure 2 displays the dynamics of household debt (auto, home equity, and credit card) in the nine quarters that follow a minimum-wage increase. The figure clearly shows total debt rising in the first year after a minimum-wage increase for households with income below $20,000 (blue line) who probably include minimum-wage workers, but not for higher-income households (red line). In subsequent quarters, debt rises by less, to the point that by the end of the second year, we cannot reject that debt among low-income households is beginning to fall. This pattern provides direct evidence that much of the early consumption response is in fact debt-financed, and corroborates the independent CEX measures of debt-financed vehicle spending and the large spending estimates.

Now I am sure moralists somewhere will look at this result and tisk tisk over the irresponsibility of poor people. But this information raises more complicated questions that merit further study. I didn’t look at a lot of metropolitan areas, but the ones with decent public transportation that I looked at all had living wages above the $9 level. Most places in America require having a car. Depending on relatives or friends for transportation is a risky proposition, particularly for low wage workers, where one absence often leads to being fired. So getting a car, or trading in an old one (that might be at risk of needing costly repairs) may not be as dodgy as it looks from 50,000 feet. Similarly, the spending increase tapers off over time, suggesting some element of pent up spending is at work (home repairs? desperately needed dental work?). This pattern seems to illustrate the treadmill the poor are on, that until you are earning a living wage, even getting more money merely means trading one form of desperation for another.

Nowadays I am grateful that I could never find that cubicle job I’d always dreamed of, with it’s constant demands and petty stresses, despite graduating from college and getting part way through a master’s degree.

Being involuntarily cut off from that draining and demeaning lifestyle was a blessing in disguise (and as an bonus I’m now contributing almost nothing to this sick and failing culture, which has additional psychological and practical benefits for me).

I hope that everyone else could see too that there are better things in life than simply scrabbling desperately for fiat money with which to buy cheap plastic crap from China that will be thrown in a landfill in a few months. Because if that’s what improving the economy means we and the earth are better off rid of it.

Dear contented moralist: People don’t go into debt over cheap plastic crap from China. It’s cheap.

Consumerism is a dying doctrine that is causing untold misery around the world with its unceasing drive to turn precious, irreplaceable natural resources, and the labor of human beings, into fiat money. If only you could see how your lust for fiat and desire for economic growth is inextricably linked to the pillaging of the earth and the denigration of humanity.

But there is a solution to that problem, if only on the personal level: those of us stuck in the dying system can opt-out and experience psychological well being; or we can make ourselves miserable hoping and praying to join or continue living an unsustainable lifestyle that is already on its deathbed. That’s not a moralism; it’s just the way things are.

As far as poor people taking on debt goes? Well, if you have a debt, then repudiate it. Now. If everyone would do the intelligent thing and stop paying these ridiculous, odious debt that this amoral and corrupt system has foisted on us, then all the fraud and corruption that NC is constantly harping about would simply go away overnight. Look, NC readers don’t like all the “TBTF” banks and corrupt politicians that are running around, right? Well stop giving them money already. And better yet, stop supporting policies that allow them to print their own money.

Yes, all that is generally true, but there’s no use in laying it on the poor. What you call consumerism includes essentials, after all, and most are simply scrambling for teeth repair, new glasses, a medical visit, and a car that works in a regular fashion.

“Lust for fiat” and “desire for economic growth” are the bailiwick of those with money and power.

Yes, our society still grabs up resources beyond legitimacy and it will likely all end in picking bones, but what would you have these people do? Going into debt for above-mentioned needs and then simply refusing to pay might work once.

The poor are aware, in every moment of their lives, that they are living in a dying society. People need ideas and support. You likely have some practical proposals for how to develop a healthy life outside the system that is destroying us. Take a neighborhood, any poor neighborhood. How do you suggest they get their teeth fixed?

Friends;

Twenty years ago, the teenage son of one of my co-workers on a commercial project needed money and pawned the title to his truck. It wasn’t new, but well kept up and decent looking. Dad had helped with the initial payment. Sonny Jim started working on the project during the summer. (Nepotism is a universal vice, it seems.) Embarrassed to go to his dad, he turns to what he perceived to be his dads’ near peer group for advice. When a couple of us sat down to work out the figures with him during lunch we received a rude shock. When you included the monthly ‘service fees,’ he was paying just over 300% interest!

This was not a stupid young man. He was a local high school senior, and nearly certain to progress to the local Community College for what now passes for the old Apprenticeship Programs. He just hadn’t been taught anything about personal finance in his education. Are todays youth being treated any better? I learned what I know about the subject from watching my mom and dad manage a small ‘one horse’ plumbing company. School gave some information, but no hands on instruction. If I were cynical, I would suspect that the dearth of personal financial instruction in the schools today was a feature.

Any pedagogues or recent school graduates have fresh information on this for us? I’ve been out of the formal academic arena for nearly four decades now. Fresh viewpoints and information would be of great service.

Just thinking aloud here, but, perhaps we should take a page out of the Fundamentalist Conservative game book and start organizing to take over local school boards. Look at how successful this has been for the forces of reaction in Texas!

Yoiks and away!

I agree with everything you said. High schools should institute a new “home economics.”

The predominant trend in the educational industrial complex seems to be merely multiplying increasingly narrow cast certificate and degree program where graduates may or may not get such narrowly defined jobs.

Driven by those who see education purely as job training, this seems largely counterproductive for students, despite the moral stridency of its proponents. Practical degree = job and economic security seems spent, in all social strata.

Community colleges could be preparing people to start and grow small businesses (or other viable self sustaining local organizations), and develop on-site (or locally situated) small business resource centers.

I think this last is important. This is a lot better than the factory conveyor belt “drop ’em off at the end and hope you never hear from them again” model they us to rip people off with now.

Education for a job and educating people to start small businesses might serve different “educational markets” but overall it might serve the community better.

Two numbers caught my eye in the living wage’s detailed expense breakdown: (1) With a minimum wage around $9.00, two incomes will be required to 2-adult families to reach the living household wage. Perhaps accordingly, the living wage budget provides for two cars, but $0 is allocated for childcare. (2) The budget allows $0 for savings.

Yeah, the living wage numbers seemed unreasonably low to me, as well. So even these researchers are adding to the BS by claiming that a “living wage” doesn’t need to include childcare (?!?) or savings.

I believe it was WORD, or maybe the New Party, who calculated a living wage for Montana back in the early aughts (2001-2004 sometime). It was well over $9.00 then for a single individual. IIRC, it was $10 for a single, $14 or $15 for a family with one kid (including some savings every month).

Minimum Wage Households That Get Pay Increases Typically Increase Their Borrowing Even More

Of course. When the counterfeiting cartel is lending the choice for most is borrow from it or be priced out of the market by those who do borrow.

I used to think that a core value of Americans was “Thou shall not steal” but I see I was mistaken.

This makes sense to me. When you’ve done without for a while, an expected steady stream of incremental income can be leveraged to get stuff today that you’ve been putting off for some time. A car would be a good example. If I’ve been putting up with my ole falling apart car for the past few years because I can’t afford and upgrade and I come into a few hundred dollars a month, I can now afford the loan on the new (or at least less used) car that will get me back and forth more reliably.

In more scholarly terms, you could call it pent-up demand. The increase in income leads to an increase in available credit that can be used to satisfy the pent-up demand.

ding, ding, ding!!!

Most of the spending is on durables, not vacations to Disney land.

And we all know that the 1%ers have never gotten themselves in trouble by going into a bunch of debt right? I guess if you call it “leverage” it’s different somehow.

“trading one form of desperation for another”

A fine restatement of the American Dream.

Forget baseball. Screwing the poor is our national pasttime. Is there a homegrown version of Hugo Chavez out there? Your time has come.

Re: having a car. Not only for work, but also for getting kids to school on a schedule that may not comport with a schoolbus schedule – many schools are open early and late with child care options for working parents….Further, even with good public transport, living in an urban area is often too expensive, so living in the ‘burbs necessitates at least some kind of vehicle, if only to get to the centralized bus terminal.

I would also bet that auto loans are easier to get than other kinds of credit, such as revolving charge accounts, and what store has them anymore, anyway?

SPAM! just flagging in case the NC PTB missed it ;)

Cheers Yves. This post is yet another example of something way too rare in your (Boston-DC) neighborhood in that you attempt to get to grips with the reality of most Americans and their dependence on automobiles to make a living.

My take is that lots of low-income people are forced to live with unreliable transport. They own vehicles that could up and die at any moment, and must be repaired at unpredictable intervals. That’s “must” as in MUST… no wheels, no job.

Ditching the beater for a more recent model car gains better gas milage and reduces a major nagging anxiety while boosting self-image. Small wonder that’s a popular choice.

I’d like to see data on places where there’s “transport as public service” (big cities) v where there’s “transport as personal investment” (suburbs & rural). Also, seems likely that predatory rates on vehicle debt would be likely for folks in this situation so info on debt service cost increase v wage increase would be illuminating.

1. When a worker moves up from minimum wage to 9.00 per hour, he loses benefits that he used to qualify for. (housing, food, childcare, sometimes public transportation)

2. 9.00 an hour is not enough to get any needed dental care.

3. …or a car

4. in some places a one day bus pass is 6.00 or more!

American businesses need to take care of their workers! The work must be done, but no one cares if the workers are healthy or safe.