Yves here. This post makes some important observations about how the elite levels of Greece engage in rent-seeking, aka corruption, and can continue those strategies even in the face of economic collapse, to the detriment to the rest of Greek society. It’s an important counter-frame because many accounts of what has happened in Greece fails to take sufficient account of the role of parties within Greece of profiting despite increasing desperation overall.

One can correctly point out that that focus leads the authors to place too much confidence in cleaning up tax evasion and other “reforms” focused on rentier behavior as having enough impact to get Greece out of its very deep economic ditch. But I trust readers have the sophistication to read past those parts and focus on the analysis, particularly since advances economies like the US are at an earlier stage of slipping down the corruption slope.

By Christos Koulovatianos, Professor in Macroeconomics, University of Luxembourg and John Tsoukalas, Associate Professor (Reader) in Macroeconomics, Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow. Originally published at VoxEU

As numerous Greek MEPs opposed the Eurozone summit deal, implementation will require a broad coalition of political parties. This column argues that corruption in Greek politics will prevent the formation of such a coalition. The heavy debt service leads parties to invent extreme ways of responding to super-austerity and to strongly oppose direct reforms that challenge existing clientelism. The way out is to sign a new agreement that combines debt restructuring and radical transparency reforms, including naming-and-shaming practices, to block clientelism in the medium and long run.

Corruption is typically unobserved in formal data, so it is difficult to document its extent. Since the work of Schattschneider (1935), theories of rent seeking and corrupt legislative bargaining – further developed by Ferejohn (1986) and Persson (1998), and outlined in the book by Persson and Tabellini (2000) – link up the observable effects of corruption to rent-extraction mechanisms. These theories help in estimating rents, but we are unaware of a study that obtains such estimates for Greece. Nevertheless, everyday life in Greece suggests that clientelistic goods traded by political parties include examples such as:

• Civil-servant jobs, for which devoted party members can put in less effort at work, and for which party members may be underqualified.

• Tax evasion, with parties supporting networks of non-transparency through insiders in public authorities.

• Preferential legal treatment using a partisan network of underreporting through public authorities.

• Privileges regarding the management of real estate.

• Fiscal over-invoicing.

• Wasteful public infrastructure related to private benefits, such as building roads leading to specific private properties against city-plan efficiency.

• Fraud in granting disability benefits (Angelos 2012), etc.

Corruption in Greece Relative to Other Eurozone countries, and Its Fiscal Profligacy Problem

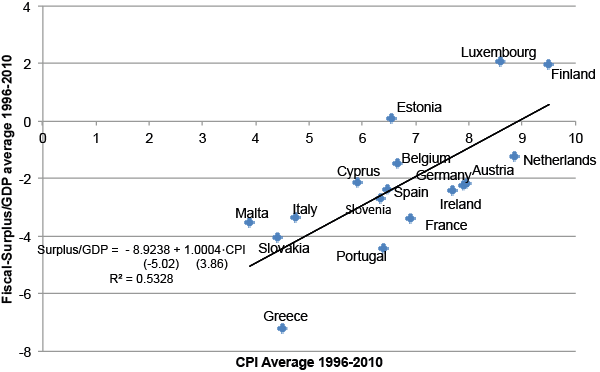

Figure 1 plots the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) against the average fiscal surplus between 1996-2010. As can also be seen in Table 1, Greece is one of the countries with the highest corruption (CPI) scores. According to Figure 1, Greece is certainly the Eurozone’s outlier in terms of fiscal profligacy. Fiscal surplus to GDP ratios have a correlation coefficient of 73% with the CPI, revealing that corruption is strongly related to fiscal profligacy. Achury et al. (2015) provide a theoretical analysis suggesting a two-sided causality between fiscal profligacy and corruption if a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio is too high (beyond 137%). In that case, a country can be trapped in a vicious circle of corruption and fiscal profligacy that ultimately leads to default. The key to this vicious circle spiral is the unwillingness of rent-seeking groups to cooperate on reforms and on minimum fiscal prudence.

Figure 1 Correlation between the fiscal-surplus/GDP ratio (in percentage points) and the Corruption-Perceptions Index (CPI) for Eurozone countries (t-statistics in parentheses).

Note: For Cyprus, Estonia, Malta, Slovakia and Slovenia averages are calculated since four years prior to joining the Eurozone.

Sources: Eurostat, Transparency International; figure taken from Achury et al. (2015).

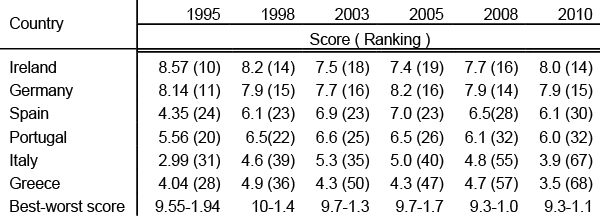

Table 1 Corruption Perception Index (CPI)

Note: Higher score means lower corruption and numbers appearing in parentheses next to each score is the country’s world-corruption raking based on the score in each particular year.

Source: Transparency International; table taken from the Online Appendix of Achury et al. (2015).

Why Cooperation Among Political Parties Matters for Reform Implementation

The immediate argument in favour of broad coalition governments is that policy reforms and austerity have a high political cost. Cooperation among parties can make them share the political cost. In addition, a broad consensus among parties provides credibility to society concerning technocrat-expert suggestions for solving the fiscal profligacy problem. From the very beginning of the sovereign crisis in the Eurozone, the IMF has provided explicit guidelines in favour of broad coalition governments or for cooperation across parties (see International Monetary Fund, 2010a-d, 2011a-f, and 2012a-f for specific sentences expressing these IMF guidelines).1

In the case of Greece, coalition governments have never been broad across parties, and reforms have progressed slowly, despite the intense monitoring by the IMF (Campos and Coricelli 2015). According to the theory suggested by Achury et al. (2015), the corruption problem in Greece, combined with its high debt-to-GDP ratio, has led Greece into a trap.

What Causes the Corruption-Debt Trap in Greece?

According to the approach of Achury et al. (2015), corrupt political parties in Greece tend to act as rent-seeking groups through the provision of clientelistic goods described above. Cooperation on reforms and austerity measures is a typical coordination game. If the partisan benefits from cooperation exceed the partisan benefits from non-cooperation, then two equilibria are possible: cooperation and non-cooperation, with the latter being the result of bad coordination. If, however, the partisan benefits of non-cooperation exceed those of cooperation, even for one big party, then there is only one sure outcome: non-cooperation (Achury et al. 2015, Section 1.1).

The high cost of servicing the enormous outstanding debt in Greece simply makes non-cooperation more profitable for parties. If parties cooperate, they face a high cost of servicing the debt, especially due to the tight fiscal-surplus requirements. This fiscal burden makes party members think that a partial default and a gang war for rents is more profitable for them, even in a state of economic chaos. This strategic speculation keeps Greece in a trap, because non-cooperating rent-seeking groups engage into a tragedy-of-the-commons equilibrium of excessive rent seeking. Markets pre-calculate the implied fiscal profligacy, Grexit scenarios return with positive probability, investment becomes discouraged, and the debt-to-GDP ratio increases due to a shrinking economy (Greece has lost 26% of its 2008 GDP until year 2014).

The Short-Run Solution and the Long-Run Solution for Escaping the Political Infeasibility Trap: A Synthesis

The ideal long-run solution to Greece’s problem would be to eradicate rent-seeking groups in politics. However, this requires time and a deep understanding of the problem. The short-run solution would be to restructure Greek debt, postponing payments and giving enough time for economic recovery. This short-run strategy could make benefits from a broad-coalition government more attractive to political parties, because it would take away the debt-servicing burden. The working hypothesis is that some rent-seeking activities would still be speculated by parties (Achury et al. 2015, Sections 2.5, 3.1.2, and 3.1.4).

Of course, such debt restructuring requires a new agreement. And certainly the EU should ask for reforms in exchange for debt restructuring. Whether these reforms could solve the corruption problem (or not) in the long run, is a matter of understanding the roots of the corruption problem in Greek society.

The vast majority of Greek citizens are not corrupt: Corruption is a social coordination problem leading to a prisoner’s dilemma

A small but critical mass of citizens and politicians break the rules of fair play and equitability against the law. Businesses that do not pay their taxes oblige other businesses to do the same in order to survive competition. Skilled young people who apply for civil servant jobs are obliged to invest in clientelistic political connections, after seeing inapt persons obtaining such jobs. Citizens see their taxes ending up in the private pockets of people they know, but are unlikely to win a court case because of the political support for involved persons. Lawful citizens, knowing that taxes will not finance public goods but private benefits, are unwilling to pay their income taxes, becoming friendly to parties that promise lenience regarding tax collection.

The list can go on and on, but the issue is not morality. It is the technical perils of a coordination problem that ends up in prisoner’s dilemma situations that arise in everyday life. The sad equilibrium is that Greek citizens do not feel equal among equals against taxpayer law. A feeling of social mistrust pervades citizens, especially young people.

Can society and the partisan network of vividly supporting voters and politicians bring reforms to Greece? This is not likely, unless a key reform is implemented first: transparency. Greece can innovate on that front, making use of information technologies.

Basic Things About Transparency First

A key transparency reform is to put every Greek citizen’s existing personal data into a centralised database. Currently, such data are scattered across different public authorities, a strategy that is most likely intentional. This strategy has led to frivolities with tragic fiscal consequences. An example is the famous disability fraud of certified taxi drivers receiving blindness disability aid in the island of Zakynthos (Angelos 2012). Because of the radical nature of this reform, it is crucial to protect privacy rights in the transition phase.

A Careful ‘Name and Shame’ Transparency Act

Another key transparency reform would be to list the names of all Greek citizens on the web, explaining who has paid all taxes, and if not, the stated reason why. This act should fully protect personal data, such as income and wealth records, exactly because political rent seekers inside and outside Greece may attempt to confiscate wealth through ad hoc bail-in acts. If implemented correctly, this reform is most likely to convince Greek citizens that everyone is equal among equals against taxpayer law. This sense of equality can lead to a new social contract that can fight clientelism and pork-barrel politics, restore social trust, and bring policy certainty. In turn, policy certainty can give confidence to domestic and foreign investors to unlock Greece’s potential for innovation and growth.

Conclusion

The implementation of the ‘aGreekment’ reached on 13 July 2015, after a 17-hour Eurogroup summit, needs a broad coalition government in Greece. The urgent and necessary political cooperation among parties is unlikely to be forthcoming. Political parties have rent-seeking agendas that are crowded out by the burden of servicing the debt. This is a trap.

To escape this trap, we suggest an urgent additional agreement. Drastic debt restructuring (postponing debt maturity) should be exchanged with immediate implementation of radical transparency reforms that aim at eradicating corruption. Debt restructuring should convince rent-seeking political parties that it is more profitable to cooperate. In the short run, parties could keep a small part of their rent-seeking activities, while servicing a smaller, manageable amount of debt.

It is impossible to instantly reverse the momentum of political corruption in Greece, but it is urgent that parties first cooperate on implementing simple and basic transparency reforms. In the beginning, the political cost of implementing these transparency reforms will be low. In the medium and long run, transparency can raise the feeling of equitability among citizens. This feeling can encourage Greek society to move away from supporting rent-seeking parties and to demand governments with public-resource management skills.

See orignal post for references