A case filed at the end of last year, Mayberry v. KKR, hasn’t gotten the attention it warrants. The suit, which we’ve embedded at the end of this post, was filed on behalf of the beneficiaries of Kentucky Retirement Systems (KRS), the state’s public pension fund and its taxpayers, against Blackstone, KKR/Prisma, and PAAMCO for engaging in a civil conspiracy and violating its fiduciary duties under Kentucky law by misrepresenting what it calls “Black Box” hedge fund products. One of the eight plaintiffs is a sitting district court judge.

In addition to suing the top executives at these funds, including Henry Kravis and George Roberts of KKR and Steve Schwarzamn of Blackstone, the filing also targets four former and three current KRS board members, four former KRS administrators for breach of fiduciary duties, along with KRS’ fiduciary counsel, several financial advisers, its actuarial adviser, and a firm that certified its Comprehensive Annual Financial Report.

The fund managers allegedly focused on KRS and other desperate and clueless public pension funds who were unsuitable investors, particularly at the risk levels they were taking. KRS made what was a huge investment for a pension fund of its size. $1.2 billion across three funds all at once, in 2011, roughly 10% of its total assets at the time. They all had troublingly cute names. The KKR/Prisma funds was “Daniel Boone,” the Blackstone fund was “Henry Clay” and the PAAMCO fund, “Colonels”.

In the case of KKR/Prisma, the fund had installed an employee at KRS as well as having a KKR/Prisma executive sitting as a non-voting member of the KRS board. The filing argues that that contributed to KRS investing an additional $300 million into the worst performing hedge fund even as it was exiting other hedge funds. 1

The suit seeks damages for losses, recovery of fees paid to the hedge funds and other advisers, and punitive damages. The damages would go to KRS and the suit also asks that the court appoint a special monitor to make sure the funds are invested properly.

Some observers may be inclined to see this litigation as having only narrow implications, since KRS is fabulously underfunded, at a mere 13.6% funding level with only $1.9 billion in assets, and famously corrupt. KRS not only saw its executive director and chief investment officer fired over a 2009 pay to play scandal, but more recently, it had the astonishing spectacle of having the governor call in state troopers to prevent the KRS chairman, Tommy Elliot, from being seated. 2

Charming, no? But with so much bad conduct out in the open, it’s not hard to see why analysts might assume that Kentucky is so sordid that a suit there, even if it proves to be highly entertaining, is relevant only to Kentucky.

That may prove to be a mistake. As one former public pension trustee said,

This is the equivalent of going from a confrontation between the public pension industry and some people throwing rocks to a confrontation against the Soviet Army. Bill Lerach, the guy behind this is as serious as they come. Don’t let the fact that he was disbarred in any way fool you.

Lerach’s wife is a Kentucky native and one of the lawyers representing KRS. Her husband’s firm, Pensions Forensics, is an advisor to this case.

Lerach has a net worth estimated at $900 million, which is plenty of firepower to fund expenses on a case like this. Two different readers in Kentucky (neither of them Chris Tobe) separately informed me that the Kentucky attorneys pleading the case are formidable. As one said by e-mail:

Anne Oldfather is a local lawyer with a fearsome reputation and not to be taken lightly and not prone to settlement of any cases.

The case has also been assigned to the most progressive judge in the state.

The stakes for the defendants are high. The giant fund managers do not want to be found liable for misrepresenting their products, since a loss in this case would expose them to many other suits. But the plaintiffs appear not inclined to settle, plus a settlement with a state entity may not be secret (they aren’t in California). That would reduce the defendants’ incentive to agree to anything bigger than what they could argue was a token payoff

But as we discuss below, this case also has serious implications for pension trustees and advisers all over the US.

The filing makes persuasive arguments about how all-too-common practices, like the overstatement of expected returns, which in turn leads pension actuaries, trustees, and legislatures to seek too little in the way of current contributions, is a breach of fiduciary duty. If the court were to rule in favor of the plaintiffs on the overstatement argument, it would send a shock wave across the pension world. Many supposedly well-run public pension funds like CalPERS engage the behaviors that this case credibly depicts as violations of fiduciary duty.

The legal team on this case would like to conduct a Sherman’s march through the many parties that have sat pat or benefitted from public pension fund grifting. From Bloomberg:

Plaintiff attorney Michelle Ciccarelli Lerach said her law firm and three others behind the suit believe it could open a new path for state and municipal pension systems to seek compensation from managers of other alternative assets. Kentucky state law, she said, provides considerably more latitude than federal securities law to hold “control persons” personally liable for the actions of the entities they supervise… “And, as we’ve alleged in the complaint, each of the managers, actuaries and pension advisers owes a fiduciary duty under Kentucky law. It’s not a stretch to say they’ve breached it.”

The case is very readable, although it has some sour notes, like trying to depict Blackstone’s Steve Schwarzman, who left Lehman in 1985, as somehow being responsible for the firm’s collapse.

First we’ll discuss the case against the fund managers, then against the trustees and other insiders.

How Blackstone, KKR/Prisma, and PAAMCO Picked the Pockets of a Clueless and Desperate Pension Fund

The filing makes arguments that will sound all too familiar to anyone who has been watching the public pension fund world. KRS was overfunded at the peak of the dot com era, took a whack in the bust, and took an even bigger hit during the financial crisis. The case contends that KRS’s current effectively bankrupt state wasn’t a foregone conclusion, since many public pension funds are over 80% funded.

As we discuss in more detail below, the filing describes the desperate state of KRS and how the “Black Box” hedge fund sellers appear to have taken advantage of KRS’ sorry situation. The filing stresses the opaqueness of the investments, which were hedge funds of funds, and does not weigh as heavily as it might upon the fact that KRS was paying a layer of extra fees when the size of its investment was so large, over $400 million per fund, that it could have gotten adequate diversification without hiring pricey middlemen. The filing does argue that hedge fund investments have been a lousy bet, as we reported in the very first post on this site, in 2006.

The plaintiffs have not yet obtained the return data from the three funds at issue. But the reported “absolute return” strategy over the period, which the plaintiffs believe consists primarily, and likely entirely, of their total results, was under 4% per annum for the five fiscal years ended June 2016 versus an average annual return of 11.9% for the S&P 500 over that time period. One might argue that an absolute return strategy, being somewhat contra-cyclical, could be expected to do less well than the S&P 500. But that does not appear to be what KRS was led to expect.

The filing depicts Prisma as having preyed upon KRS as unsophisticated and needy and as misrepresenting its “Daniel Boone” fund as high return and low risk. One of the most telling parts of the filing is where it contrasts how the funds were described to KRS as opposed to in SEC registered filings.

This bit is also ugly:

As the Daniel Boone Fund began to lose millions in 2015-2016, KKR/Prisma, Roberts, Kravis, Reddy and Cook helped to arrange for a KKR/Prisma Executive to work inside KRS while still being paid by KKR/Prisma. Reddy and KKR/Prisma referred to this arrangement as a “partnership.” Subsequently, while Cook and Peden and the KKR/Prisma executive were working inside KRS, KKR/Prisma sold $300 million more in Black Box vehicles to KRS despite that KRS was then selling off over $800 million in other hedge funds because of poor performance, losses, and excessive fees and the KKR/Prisma Black Box was the worst performing of the three. This very large sale to KRS was a significant benefit to KKR/Prisma, which was then suffering outflows due to customer dissatisfaction over poor results and excessive fees.

One of the key questions is how the big fund defendants will respond in court. The usual approach is to say that the parties who lost out were sophisticated investors and that anyone who invests knows that nothing is guaranteed. Moreover, if the hedge funds agreements resemble private equity agreements, they may include language that is tantamount to a waiver of fiduciary duty. To my knowledge, no one has tested whether these provisions are enforceable; I can think of reasons (the staff and trustees cannot legally waive those duties; the provisions are contrary to public policy and hence not enforceable) why they might not survive a legal challenge.

In addition, fiduciary duty imposes a high standard of conduct, and at least so far, the defendants don’t appear to be trying to duck that. From Bloomberg:

“We take our fiduciary duty very seriously and believe that the allegations about our firm are meritless, misplaced and misleading,” Cara Major, a spokeswoman for KKR, said in an email.

How KRS Trustees, Administrators, and Hired Guns Sold Out the Fund Beneficiaries and Kentucky Taxpayers

Significant parts of the case discuss how the parties duty-bound to serve the welfare of the beneficiaries and the state instead put their own financial and/or reputational interests first. For instance, the filing states:

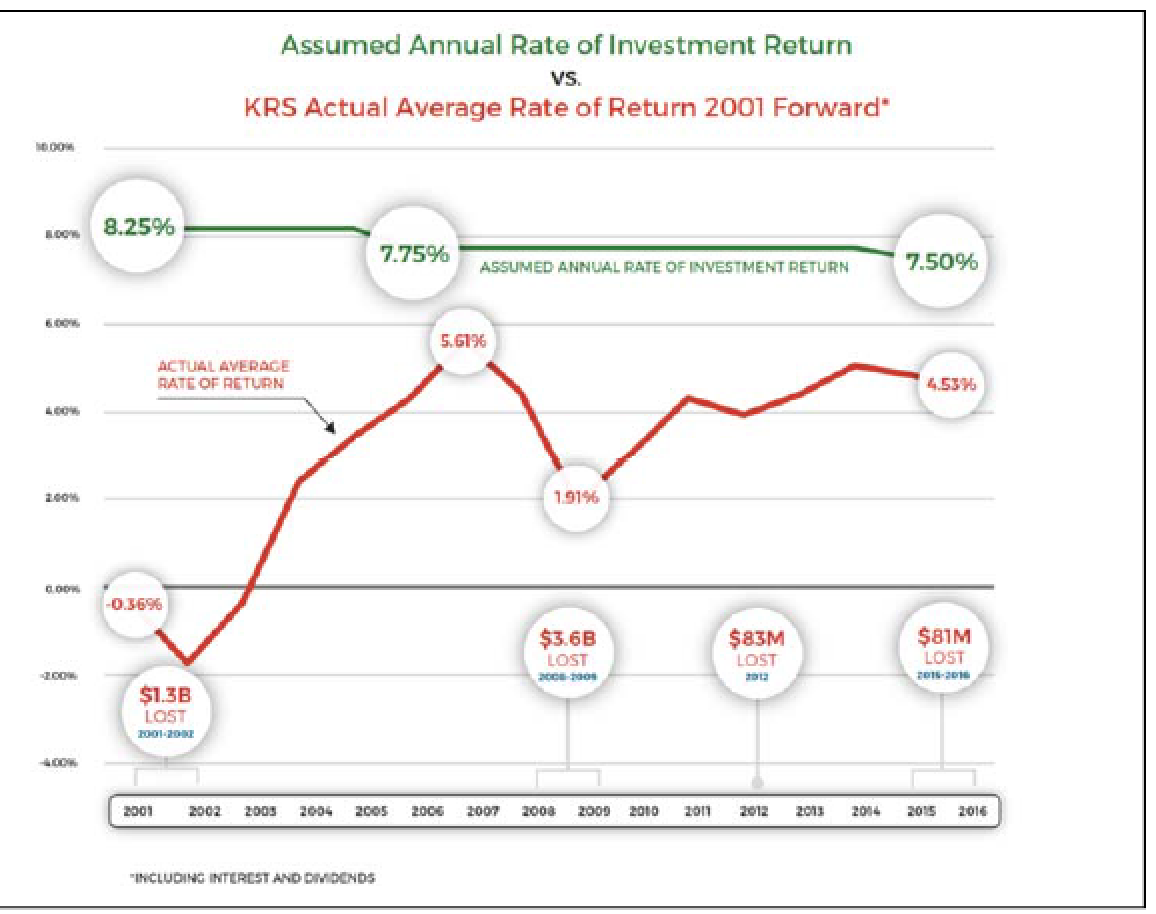

After these losses, the trustees4 received studies which revealed that the financial condition and liquidity of the Funds were seriously threatened and far worse than was publicly known. The trustees had been utilizing outmoded, unrealistic and even false actuarial estimates and assumptions about the Pension Plans’ key demographics, i.e., retiree rates, longevity, new hires, wage increases, inflation. For example, Trustees used an assumed 4.5% yearly governmental payroll growth when new hiring rates were near zero or negative and interest rates were too. Most importantly, KRS’ assumed annual rate of investment return (“AARIR”) of 7.75% was not realistic.5 Nevertheless, Trustees and other Defendants continued to use assumptions that were proven to be dead wrong by the actual figures established since 2000. From 2000 through to date, the Funds’ cumulative moving average annual rate of return has never even come close to that “assumption.”

It isn’t just that the trustees continued to use unrealistic return assumptions, as shown above. The fact that they also apparently had “false actuarial estimates” and stuck with rosy payroll growth assumptions makes this look like a continuing “kick the can down the road” exercise, that with the long time horizons of pension funds, the officials in charge could hide the problems, or somehow generate miraculous returns and earn their way out of their hole.

But as anyone who had managed professional traders knows, someone sitting on losses is particularly inclined to take “swing for the fences” risky bets or even engage in illegal activity to try to recover.

Enter what the filing calls the “Black Box” hedge fund sellers. It is remarkable that the trustees contemplated this type and scale of investment after the fund had been caught out in “pay to play” scandal involving its first investment in “exotic” alternative structures in 2009 that resulted in the firing of its Executive Director and Chief Investment Officer in 2009, a mere two years earlier.

The filing contend that by 2010, the trustees, administrators, and other advisers knew KRS was in a deep hole and were lying to the public about it:

All defendants also realized that if they honestly and in good faith factored in and disclosed realistic actuarial assumptions and estimates and investment returns, the admittedly underfunded status of the Plans would skyrocket by billions of dollars overnight, that there would be a huge public outcry, that their stewardship and services to the Funds would be vigorously criticized, and that they would likely be investigated, ousted, and held to account.

The reason this case is potentially so significant for other public pension funds isn’t simply that the fact set above serves as motive for investing in unduly risky products without asking tough questions, that the insiders were desperate for any way out even if they should have known that what they were buying was hopium. The filing makes a strong argument that the mere fact of misrepresenting the true condition of the fund was a violation of fiduciary duty and other state laws.

Other lines of argument that could apply to many other public pension funds include:

Inadequate fiduciary training of trustees. Fiduciary counsel Ice Miller is a named defendant in the suit for this lapse. Ice Miller is separately alleged to be responsible for the officers and trustees of KRS not having sufficient directors’ and officers’ insurance, which the filing argues should be $300 million as opposed to $5 million.

Misleading and incomplete disclosure of KRS’ financial condition in its Annual Report. The filing depicts this breach as a serious failing and holds many parties liable, including the trustees, the fiduciary counsel, financial advisers that supplied signed representations included in the financial reports, KRS’ actuary, and of course, its accounting firm.

One amusing tidbit is the inclusion of the “Annual Report Certifier,” the Government Finance Officers Association, as a defendant. Note that CalPERS makes much of the fact that the Government Finance Officers Association also certifies its reports. From the filing:

According to GFOA, it conducts a very thorough review of any pension trust or plan that applies for a Certificate of Achievement in financial reporting…

GFOA’s business model depended on selling a large volume of public pension funds memberships/certificates/endorsement and awards and thereby generating revenue…The larger the fund the larger the fee. GFOA also charges a size-based fee in return for issuing its Certificate and Achievement awards, in effect taking fees and dues in return for handing out prestigious sounding and looking awards and certificates but doing no real research or investigation, nor any skeptical, detailed, independent review or evaluation.

The case contends that the GFOA had incentives to continue to give KRS’ reports awards in the face of evidence that they were dodgy:

GFOA depends upon the monies it gets for issuing these certifications and advertisements to public pension plans. If it suddenly withdrew or refused to continue giving the annual awards and certification to KRS, that would have raised red flags, pension funds would have shied away from using GFOA which could have threatened GFOA’s volume-driven, hand-out-the-certifications-in return-for-the-money, business model. GFOA chose to continue its awards and false certifications to KRS in order to benefit its own economic self-interest.

Mind you, this is far from the most important allegation of corruption in this suit. But it serves to demonstrate how deep the rot is and how many parties profit from it.

As Lambert likes to say, pass the popcorn. If the plaintiffs in this suit are as bloody-minded as they appear to be, a lot of dirty practices will be exposed, and the perps will have a hard time maintaining their usual plausible deniability defenses. If we are lucky, this suit will force a long overdue day of reckoning in public pension land.

____

1 For the purpose of simplicity in this post, we refer to Blackstone and KKR/Prisma. In fact, all of KKR, Prisma, and PAAMCO are included among the defendants in this suit. It was Prisma that sold the hedge fund investment to KRS in 2011. KKR had been trying to buy Prisma bolster its hedge fund business since 2010 and acquired Prisma in 2012. Last year, KKR/Prisma merged with Pacific Alternative Asset Management to form PAAMCO/PRISMAHOLDINGS. The new entity manages the former KKR/Prisma hedge fund operations. The filing also spills some ink on the fact that convicted hedgie S. Donald Sussman had a substantial ownership stake in PAAMCO which it alleges, based on a 2010 New York Times story, that founder Jane Buchan and Sussman conspired to cover up:

Sussman had a background Buchan wanted to conceal from potential investors, customers and regulators, as he had been convicted of dishonest behavior in connection with the investment of fiduciary monies. Buchan and Sussman created fake documents to disguise Sussman’s large ownership stake in PAAMCO as a loan, because Buchan and the other founders believed they could hide Mr. Sussman’s background from investors and regulators.

2The fact that the state attorney general backed Elliot and Judge Philip Shepherd later excoriated the Governor doesn’t mean we have a “good guy, bad guy” situation at work. This is more like a beauty contest between Cinderella’s ugly sisters. Noting that “There is no way to prove or disprove dark money,” former KRS trustee and author of Kentucky Fried Pensions Chris Tobe opined by e-mail:

367973905-Mayberry-v-KKR-KRS-lawsuitTommy Elliott (and Tim Longmeyer who is now serving a 5 year prison term for kickbacks from the related state health plan) were the fundraisers for the Gov. Beshear administration. So basically they were getting the Blackstones and KKR to give to superpacs, ie, dark money, to elect Gov Beshear’s son as Attorney General.

I believe that Gov. Bevins’ forced police removal was a loud and clear signal for Wall Street to write kickback checks to his people instead of Tommy Elliottt.

It would be something, for sure, to see these family-bloggers held to account. Pass the milk duds.

Isn’t New York one of the better-funded pensions, not due to the genius of its overseers, but due to a law (state constitution, maybe?) that mandated decent funding levels?

In a side note, the giving of awards for profit is a significant part of the business model in business journalism now, too. It’s a subspecies of (shudder) “native advertising”. Inherently corrupt, yes! Great post.

Stanford’s http://www.pensiontracker.org/index.php is a good place to look to understand state pension obligations form a numbers standpoint. Many “low tax” states are likely to be facing a bloodpath in the next couple of decades with both taxpayers and pensioners taking a significant hit.

NY does quite well from a financial stability compared to other states (in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king). NY is top in the 10 for funding ratios. The NYS comptrollers have done a pretty good job on keeping the focus on reasonable funding levels and not allowing too many games to be played without going public. NY has lots of government financial issues, but pension funding is among the better positions.

The New York State Constitution does have language in it, especially for local communities, setting rules on funding, e.g. “Each such pension or retirement system or fund thereafter shall be maintained on an

actuarial reserve basis with current payments to the reserve adequate to provide for all current accruing liabilities. ”

Statewide, there is this language: “After July first, nineteen hundred forty, membership in any pension or

retirement system of the state or of a civil division thereof shall be a contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.” Article V.7

https://www.dos.ny.gov/info/pdfs/Constitution%20January%202015%20amd.pdf

I think these are some of the key reasons why the campaign to have a constitutional convention went down in flames in 2017. I think many people viewed these and other protections as something that would be on the auction block for the highest bidder, given the Citizens United ruling.

BTW – according to pensiontracker.org, the “market funded ratio” assuming it would be funded with Treasury bonds has the best jurisdiction (D.C.) at 56%, NYS 7th at 42%, and Kentucky at 48th place at 21% funded. They use this tool to normalize states to take out the various return assumptions etc.

Good link. Thanks.

“The plaintiffs have not yet obtained the return data from the three funds at issue. But the reported “absolute return” strategy over the period, which the plaintiffs believe consists primarily, and likely entirely, of their total results, was under 4% per annum for the five fiscal years ended June 2016 versus an average annual return of 11.9% for the S&P 500 over that time period. One might argue that an absolute return strategy, being somewhat contra-cyclical, could be expected to do less well than the S&P 500. But that does not appear to be what KRS was led to expect.”

Aargh…I think this just about covers every problem with how pension funds are managed and perceived. I am constantly baffled about how something that has active payment streams coming from it are compared to the S&P 500 and why a pension fund manager would expect an absolute return fund to compare to the S&P 500 returns (hello Bernie Madoff).

Why aren’t these pension fund managers not using something rational like the “Moderate Growth Composite Index” that Vanguard uses to benchmark its Vanguard Lifestrategy Fund that is approximately a 60/40 fund? https://personal.vanguard.com/us/funds/snapshot?FundId=0914&FundIntExt=INT&ps_disable_redirect=true#tab=1

That index and retail fund did 3-year returns (as of 12/21/17) of 7.2/7.0%, 5-year of 8.8/8.6%, and 10-yr of 6.1/5.4%. It appears their hedge funds are not even doing something as good as a simple index or similar retail fund that are structured with the type of risk/volatility/return structure that a pension fund needs.

So, the big problem I see with the pension funds is not that they aren’t keeping up with the S&P 500, but that they are not even keeping up with a fairly simple four-component 60/40 retail mutual fund net of expenses that is available with a $3,000 minimum investment to any person on the street.

Forgive me my ignorance, but this looks like one of the first times the private equity black box might be cracked open for all to see. If that’s the case, it will indeed do major damage to the process of business as usual with regards to the operation of public pension funds and the products that behemoths like KKR and Black Rock can peddle to them. I agree that we need to follow this case with plenty of popcorn.

CalPERS: “Incoming!!!”

Great work highlighting this story. The sausage factory sure is a mess. Thanks!

As I understand it, these absolute return fund of funds accounted for 10% of the KPS portfolio. That sounds pretty reasonable to me. Moreover, the 4% return they achieved is just about what you should expect from an absolute return fund.

The Prudent Investor Rule, which sets the standard for fiduciaries, does not expect every single investment in a portfolio to be a winner and allows for a 10% allocation to pretty much anything.

If the allocation to these investments was, as reported, only about 10% of the portfolio, then the plaintiffs have no case.