By Ramiro Gálvez, PhD student in computer science at the Computer Science Department, FCEyN, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Valeria Tiffenberg, Developer, and Edgar Altszyler, Postdoctoral fellow, Applied Artificial Intelligence Lab. Originally published at VoxEU

The belief that men possess greater cognitive abilities than women is a longstanding and well-documented stereotype, with studies showing that both boys and girls as young as six can view ‘brilliance’ as a predominantly male trait. This column explores the contribution of the film industry in the West to perpetuating this stereotype. An analysis of over 10,000 film transcripts reveals the persistent presence of the ‘brilliance = male’ stereotype over the past half a century, including in movies specifically aimed at children.

A particularly longstanding, prevalent and well-documented stereotype is the belief that men possess higher-level cognitive abilities than women (Broverman et al. 1970, Williams and Best 1982, Kirkcaldy et al. 2007, Upson and Friedman 2012).1This ‘brilliance = males’ stereotype has even been shown to be endorsed by both boys and girls as young as six (Cvencek 2011, Bian 2017) and is believed to be a factor driving the under-representation of women in science, particularly in the STEM fields (Nosek et al. 2009, Leslie 2015, Smyth and Nosek 2015, Storage et al. 2016, Reuben 2017). Even when a consensus exists on this stereotype having strong cultural roots, studies on its perpetuation usually centre on the analysis of cultural behaviours such as differential guidance provided by parents to their offspring during shared scientific thinking (Crowley 2001) or differential guidance given by science teachers to students according to their gender (Shumow and Schmidt 2013). Notably, there is a dearth of large-scale studies focusing on the presence of this stereotype in mainstream cultural products.

In a recent paper, we study the presence of the ‘brilliance = males’ stereotype in a collection of over 10,000 movie transcripts covering half a century of film history in the Western world (Gálvez et al. 2018). As stereotypes are, in part, a collection of associations that link a group to a set of descriptive characteristics (Gaertner and McLaughlin 1983), we use natural language processing techniques to quantify associations between gender-related words and high-level cognitive ability-related words in films. In doing so, a strong focus is placed on analysing the presence of these associations in films aimed at children.

Materials and Methods

We began data collection began by downloading from IMDb a series of lists containing the 1,000 top grossing titles in the US for every year from 1967 up to and including 2016. Then, for each title in these lists, metadata was downloaded. With this data in hand, we filtered out all titles which were not movies (such as TV series), which did not include English among the languages spoken in them, and in which the US, UK, Canada, or Australia were not involved in their production. Finally, for each movie in the resulting set, its most frequently downloaded English subtitle was obtained from OpenSubtitles.2This resulted in our final sample of 11,550 film subtitles spanning half a century.

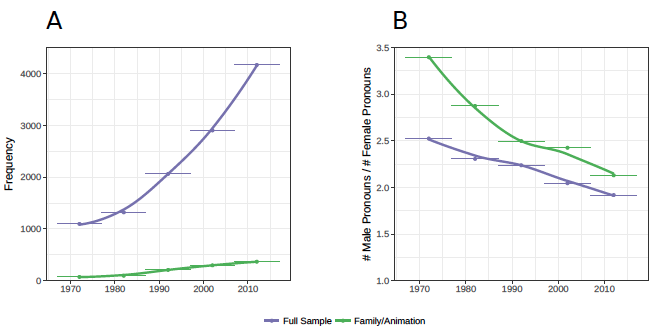

Figure 1A details the number of films analysed for successive ten-year periods (1967-1976, 1977-1986, …, 2007-2016), for the full-sample and for a sub-sample which contains only films belonging to the family and/or animation genres (family/animation sub-sample). Figure 1B shows the evolution of the ratio between the number of appearances of male pronouns (he, his, him, himself) relative to the number of appearances of female pronouns (she, hers, her, herself). In line with previous research on books (Twenge et al. 2012), in films this ratio has experienced a reduction since the mid-1960s – a phenomenon associated with an improvement in women’s status (Twenge et al. 2012) – but has been consistently less favourable towards female pronouns in the family/animation sub-sample when compared to the full sample.

Figure 1Film frequencies and gender pronouns ratios for successive ten-year periods

Notes: (A) Number of films analysed for successive ten-year periods (1967-1976, 1977-1986, …, 2007-2016), for the full-sample and the family/animation sub-sample. (B) Evolution of the ratio between the number of appearances of male pronouns relative to the number of appearances of female pronouns, for the full-sample and the family/animation sub-sample. In both panels tendencies are estimated through LOESS regressions.

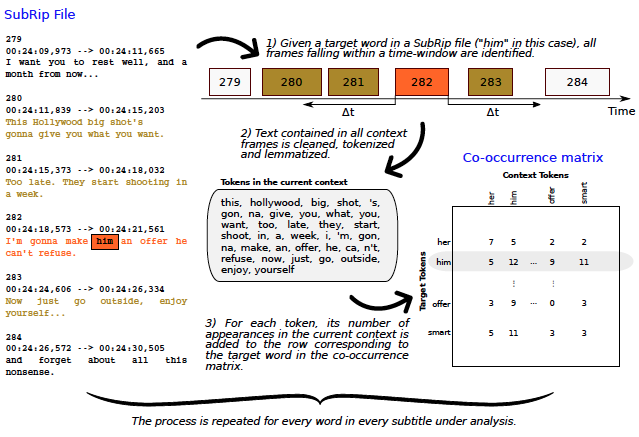

To estimate word associations between gender-related words and high-level cognitive ability-related words, we compute positive pointwise mutual information (PPMI) scores (Martin and Jurafsky 2009) between gender pronouns and high-level cognitive ability-related words (e.g. genius, intelligent, clever).3 PPMI is a metric designed to capture how much more often than chance two words co-occur (higher values meaning higher associations), and is commonly used for measuring associations between words and concepts. PPMI estimates rely on values contained in a co-occurrence matrix, which presents the number of times a word appears in the context of another one (each row representing a target word and each column representing a context word). Figure 2 contains a snippet illustrating how, given subtitle data, we built these matrices.4

Figure 2Co-occurrence matrix construction

Notes: Given a target word in a SubRip file (him in the illustration), all neighbouring/context frames are identified. Which frames constitute the neighbourhood depends on the size of a time window (Δt), which we set equal to 30 seconds. The text contained in all context frames is cleaned, tokenized and lemmatized. Then, the number of appearances of every context token is added to the relevant cell in the co-occurrence matrix under construction. The process is repeated for every word in every subtitle under analysis. A co-occurrence matrix presents the number of times a word appears in the context of another word (for example, and simply as an illustration, according to this figure smart appears eleven times in the context of him), and it serves as input for PPMI and statistical significance estimates.

Results

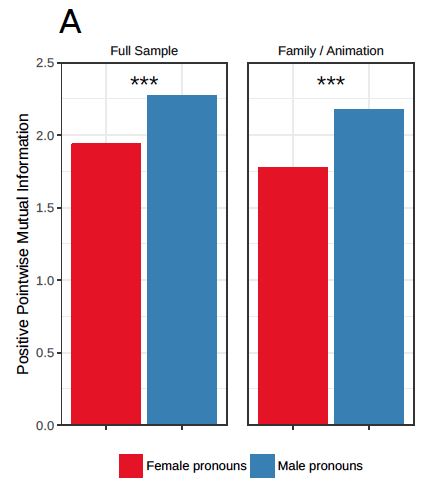

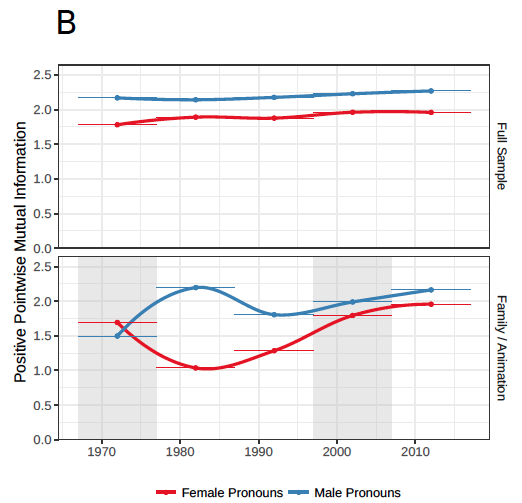

Figure 3 quantifies associations between gender pronouns and words depicting high-level cognitive ability. Figure 3A presents estimates considering all movies from 2000 up to and including 2016, for the full sample and the family/animation sub-sample. Estimates indicate that associations of male pronouns with high-level cognitive ability-related words are higher than the associations female pronouns have with high-level cognitive ability-related words. This pattern is present in both the full sample and the family/animation sub-sample. Figure 3B explores the dynamics of these differences through time. Results from the full sample of movies reveal that differences in associations have been steady at least for half a century, with no evidence of convergence in the trends. Results from the family/animation sub-sample show that differences have also been prevalent in this set of films, although estimates are less stable (we attribute this to the fact that sample sizes for every ten-year period of the family/animation sub-sample are much smaller than their full sample counterparts, see Figure 1A).5Overall, our estimates suggest that, at an aggregate level, the ‘brilliance = males’ stereotype is effectively present in films and that movies specifically aimed at children contain this stereotypical association (which we believe contributes to its early adoption). Moreover, this pattern seems to have been quite persistent for the last 50 years.6

Figure 3 Word associations between gender pronouns and high-level cognitive ability-related words

Notes: (A) Estimated association between gender pronouns and high-level cognitive ability related words when films from 2000 up to and including 2016 are analysed, for the full-sample (n = 2,902) and the family/animation sub-sample (n = 242). Asterisks indicate the results of Fisher’s exact tests on the underlying contingency tables: *** significant at the 1% level. (B) Time evolution of the estimated associations taking as input sets of films belonging to successive ten-year periods (1967-1976, 1977-1986, …, 2007-2016). Tendencies are estimated through LOESS regressions. Grey areas indicate that, according to Fisher’s exact tests on the underlying contingency tables, differences are not significant at the 5% level.

Discussion

The film industry in the Western world has been the subject of controversy in recent times regarding gender equality. Controversies range from the existence of a strong gender pay gap (actors being paid considerably more than actresses) to allegations of widespread prevalence of sexual assault and harassment. Our results suggest that gender inequality is also considerably strong in the contents of its films. Given that stereotypes regarding intelligence have been found to shape intellectual identity and academic performance (Steele 1997), the need to proactively address their presence in films is evident.

See original post for references

Given how narrowly most films pass (if they pass at all) the Bechdel test even after that became a thing, the study doesn’t seem like much of a surprise.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bechdel_test

That test is as insidious as it is profound. Even now I am gazing at the titles in my DVD collection wondering how many would pass that test. Thanks for the tip-off.

No, not a surprise at all. But the last image is a very interesting visualization of the reaction against the feminism of the ’60s and ’70s. Too bad the data only begin after 1970. It would be interesting to have the full picture of the stereotypical norm of the ’50s, the rise of feminist consciousness through the ’60s and the reaction in the ’70s and ’80s all shown in one graph.

And it is also interesting to see how early the reaction set in. My own impression from having lived through those years is that feminist consciousness continued to grow among the public throughout the ’70s. It is interesting how Hollywood began to mobilize their reaction against this movement long before it had “played out”, and it is interesting that the reaction peaked at about the time of Regan’s election. It is also interesting that the ’80s, which was the time of the yuppies as opposed to the time of the hippies, saw a decline in the reaction. One interpretation of this is that the reaction had achieved what it was meant to do, (i.e. played its role in the destruction of the feminist movement) and that it could then be relaxed. Finally, it is interesting that it settled into a new stable pattern of not-so-egregious but still prevalent sexist stereotyping.

No, none of this is particularly surprising. But it is all very interesting.

I wish I could find the link again, but apparently the stereotyping in children’s games was the lowest in the 1970s. And when I was in college, the 60s hangover meant that women didn’t feel the need to primp up for men (if nothing else, easier sex than a generation ago was enough of a hook).

As I’ve said before, you could see the effects of the backlash by the 1980s. Many women in college (this was obvious on recruiting visits) were wearing makeup and much more feminine clothing, when in my day, no makeup and jeans and a shirt (T, sweat, or turtleneck) were the norm.

Maybe this is the article you are looking for:

“Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago” by Elizabeth Sweet at The Atlantic

Not a single woman that I’ve mentioned the Bechdel test to had heard of it…

One stereotype that persists is that the STEM woman wears glasses. Also the group-of-kids-do-something-films mix usually has lead character as male, brainy one wears glasses, goofy one is not conventionally good looking, and there are subordinate roles for the token non-Nordic and female characters. Super-8 made some good steps away from this.

When one is able to stand outside the existing social order and gain a slightly different perspective, all the subtile messaging embedded in modern media becomes self evident. With that clarity, all social interaction then becomes a matter of exercising power. Some have it, some don’t.

In an oblique way, this article reminds me of the arguments concerning the best way to combat Fascism. Using logical arguments directed at appealing to reason and common decency, or raw violence. Meet violence with violence. I don’t think that dilemma was ever conclusively settled.

Until people have a choice in how they can make a living, and sustain themselves, the majority will be victim to the exploitations of those more powerful. It is easy to show people how they are being manipulated, but their actions will not change because their livelihood depends on maintaining the existing social myths.

The West was founded on violent expansion and maintained primarily with Bread and Circuses. What the author is dealing with is a fundamental contradiction of the society in which he is a part. You can’t ask the powerful individuals who control and shape that society to change their ways- they won’t.

You need to make, or control you own media studio- then be prepared for physical violence if your message is different. Barring that, convince people to use the OFF switch.

More of that, and women’s powers will surely rise quite naturally on their own. With the switch set to ON, the system produces the likes of Hillary Clinton.

While undoubtedly accurate, it’s worth noting that the sampling is limited to “the 1,000 top grossing titles in the US for every year from 1967 up to and including 2016” — in other words, exclusively Hollywood films or films which received a release from a mainstream distributor.

Hollywood films (and their European and Asian imitators) are inevitably sexist, racist, pro-war, pro-violence, and generally stupid. It was ever thus.

If the sampling were instead of 10,000 films chosen because they were not made by Hollywood studios, and did not receive mainstream distribution from the studios or the Weinstein Company, the result might read quite differently.

Be that as it may, it is incontrovertible that hollywood films have much more influence than non-hollywood films. Non mainstream films simply dont have as much pull.

The Bechdel test sets a terribly low bar, so low that it seems to be doubly useful as a critical tool and a demonstration of unexpected limits to criticism. E.g., it would have been fine with the Nazis if, after showing great victories on whatever front, the director showed women happily talking about the sunny day, their children, their Doberman, all in their nicely circumscribed life outside of the “male sphere” of Arbeit und Krieg.

Are there a succession of other, easily stated tests that begin to get at the dimensions of life and achievement the authors are trying to address? Would be great to have a scale of tests, eventually referring to a more complete, out in the public sphere and doing worthwhile things kind of existence.

Leni Riefenstahl was one of the greatest directors of all time.

She had multiple careers and lived to 102.

Her work is magnificent and can be viewed on Youtube.

I thought it was pretty well accepted that there was a meaningful gender effect on IQ with men having a slightly wider distribution of IQs across their population. Wouldn’t movies be representative of reality if there are significantly more men than women with extremely high IQ? Did the study also look at gender bias in representations of people with low IQ in movies? You might find men over-represented relative to women in that category as well.

This article argues that you can’t separate the effect of the impact of stereotyping on test results:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-theory/wp/2017/01/26/weve-been-misled-about-the-difference-between-genders/?utm_term=.840288591b0d

And as someone who got as little gender programming as is possible for someone in our society, I score extremely high on spatial ability, a supposedly strongly male aptitude. I wonder if I would do as well if I had gotten the usual conditioning.

One thing I’ve never seen addressed in such discussions is the extent to which the ‘genius’ label and associated stereotypes are correlated not so much with IQ or other intelligence metrics, but with the kind of obsessive single-minded pursuit of a goal which is so freqently linked with great discoveries – and also with early death, i.e. both obsession and propensity for risk-taking figure in.

Based on my own life experience, I’ve found that the kind of monomania which is associated with ‘genius’ and is reflected in the absent-minded-professor stereotype, to be predominantly, though not exclusively, a male trait. To what extent it is innate versus a result of gender-biased socialization is unclear, but for example:

…and continues with more citations related to differences in spatial/visualization skills, toy preferences, etc.

Would be interested to hear other readers’ thoughts on this angle.

*Sigh*

I know you mean well, but this sort of comment drives me crazy. You are actively reinforcing bad stereotypes.

Outis, who has taught math to sixth and seventh graders in public schools, attributes this to acculturation pressure. Girls who are good at math and want to pursue it with intensity are actively discouraged from doing so. They are treated as geeks and harassed by other girls. It’s OK to be a girl who is good at math without working too hard at it. That is equated to “smart girl who is going to college.”

He says the behavior change occurs around 7th grade. Girls also start competing for boys at around that age, and being too competitive intellectually is seen as s bad thing for a lot of them.

An ongoing interest of mine is how to get more women into technical fields, especially software development. I’ve tried bringing it up with our annual intern group (which is usually split about 50/50 male/female) but without much luck as most of the women simply aren’t interested in the more technical roles.

After doing some further investigation, and learning about the acculturation problem you describe, I’ve realized that it’s usually too late for them by that point and you need to reach them at about age 11-12 to make a difference. I am contemplating doing more career talks for junior classes as a result (I do these occasionally, but so far only at high schools) but I’m not sure how I would go about discussing that topic, or if it would help at all.

Ahem, you might tell readers what the criterion is before trashing it. Frankly, it sounds sensible to me:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bechdel_test

I know that it is TV and not the films but am glad to say that Star Trek Voyager passes this test with flying colours.

Two women talking in it – check! (the Captain and the Chief Engineer)

Talking for over a minute – check! (considerably longer in fact)

Not talking about a man – check! (talking about warp plasma manifolds and structural enhancements)

Yes I know that it is scifi but it is a representation of a possible future.