Lambert here: “Close to 40% of multinational profits were artificially shifted to tax havens in 2015.” Holy moly!

By Thomas Tørsløv, PhD student, University of Copenhagen and Ministry of Taxation, Denmark, Ludvig Wier, PhD candidate, University of Copenhagen, and Gabriel Zucman, Gabriel Zucman. Originally published at VoxEU

Between 1985 and 2018, the global average statutory corporate tax rate fell by more than half. This column uses new macroeconomic data to argue that profit shifting is a key driver of this decline. Close to 40% of multinational profits were artificially shifted to tax havens in 2015, and this massive tax avoidance – and the failure to curb it – are in effect leading more and more countries to give up on taxing multinational companies.

Perhaps the most striking development in tax policy throughout the world over the last few decades has been the decline in corporate income tax rates. Between 1985 and 2018, the global average statutory corporate tax rate fell by more than half, from 49% to 24%.

Why are corporate tax rates falling? The standard explanation is that globalisation makes countries compete harder for productive capital. By cutting their rates, countries can attract more machines, plants, and equipment, which makes workers more productive and boosts their wage. This theory is particularly popular among policymakers. It permeates much of the discussion about tax policy, for instance the decision by the US to cut its corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% in 2018 (e.g. Council of Economic Advisors 2017).

But is it well founded empirically? Today’s largest multinational companies don’t seem to move much tangible capital to low-tax places – they don’t even have much tangible capital to start with. Instead, they avoid taxes by shifting accounting profits. In 2016 for instance, Google Alphabet made $19.2 billion in revenue in Bermuda, a small island in the Atlantic where it barely employs any worker nor owns any tangible assets, and where the corporate tax rate is zero percent.

Mapping Where Profits Are Booked Globally

In a recent paper (Tørsløv et al. 2018) we argue that this profit shifting is a key driver of the decline in corporate income tax rates. By our estimates, close to 40% of multinational profits were artificially shifted to tax havens in 2015. This massive tax avoidance – and the failure to curb it – are in effect leading more and more countries to give up on taxing multinational companies. The decline in corporate tax rate is the result of faulty policies in high-tax countries, not a necessary by-product of globalisation.

Our estimate that 40% of multinational profits are shifted to tax havens is based on new macroeconomic data known as foreign affiliates statistics.These statistics record the amount of wages paid by affiliates of foreign multinational companies and the profits these affiliates make. In other words, they allow to decompose national accounts aggregates (wages paid by corporations, operating surplus of corporations, etc.) into ‘local firms’ and ‘foreign firms’. We draw on these statistics to create a new global database recording the profits reported in each country by local versus foreign corporations. This enables us to have the first comprehensive map of where profits are booked globally.

Using this database, we construct and analyse a simple macro statistic: the ratio of pre-tax corporate profits to wages. Thanks to the new data exploited in our paper, we can compute this ratio for foreign versus local firms separately in each country. Our investigation reveals spectacular findings.

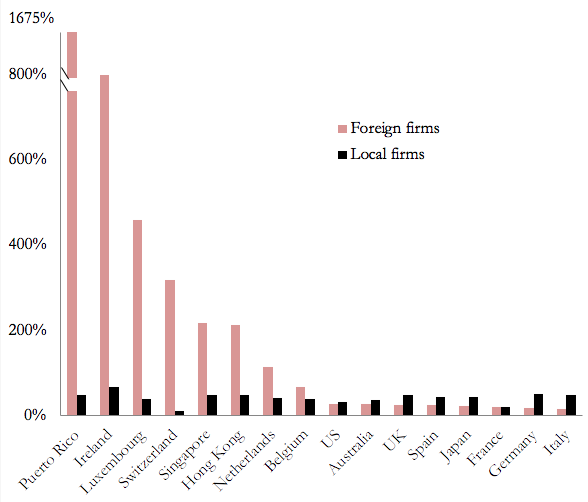

In non-haven countries, foreign firms are systematically less profitable than local firms. In tax havens, by contrast, they are systematically more profitable – and hugely so (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Pre-tax corporate profits (% of compensation of employees)

While for local firms the ratio of taxable profits to wages is typically around 30%-40%, for foreign firms in tax havens the ratio is an order of magnitude higher – as much as 800% in Ireland. This corresponds to a capital share of corporate value-added of 80%-90% (compared with around 25% in local firms).

To understand these high profits, we provide decompositions into real effects (more productive capital used by foreign firms in tax havens) and shifting effects (above-normal returns to capital and receipts of interest). The results show that the high profits-to-wage ratios of tax havens are essentially explained by shifting effects.

Overall, we find that close to 40% of multinational profits – defined as profits made by multinational companies outside of the country where their parent is located – are shifted to tax havens in 2015. Our work provides transparent, easy-to-compute metrics for policymakers to track how much profits tax havens attract, how much they gain in tax revenue, and how much other countries lose. These statistics, which we will update regularly online, could be used to monitor the impact of the policies implemented to reduce tax avoidance.

We then trace the profits booked in tax havens to the countries where they have been made in the first place – and would have been taxed in a world without profit shifting. This allows us to provide the first comprehensive view of the cost of profit shifting for governments worldwide. We find that governments of the EU and developing countries are the prime losers of this shifting. Tax avoidance by multinationals reduces EU corporate tax revenue by around 20%.

When we look at where the firms that shift profits are headquartered, we find that US multinationals shift comparatively more profits than multinationals from other countries. This can be explained by the specific incentives contained in the US tax code before 2018 and by US Treasury policies implemented in the 1990s that facilitated this shifting (Wright and Zucman 2018).

Non-Haven Countries Steal Revenue From Each Other While Letting Tax Havens Flourish

Why, despite the sizable revenue costs involved, have high-tax countries in Europe, developing countries, and the rest of the world been unable to protect their tax base? We show theoretically that the fiscal authorities of high-tax countries do not have incentives to combat shifting to tax havens, but instead have incentives to focus their enforcement effort on relocating profits booked by multinationals in other high-tax countries.

Chasing the profits booked in other high-tax places is feasible (the information exists), cheap (there is little push-back from multinationals, since it does not affect much their global tax bill), and fast (a framework exists to settle disputes between high-tax countries quickly). This type of enforcement crowds out enforcement on tax havens, which is hard (little data exist), costly (as multinationals spend large resources to defend their shifting to low-tax locales), and lengthy (due to a lack of cooperation by tax havens).

Consistent with this theory, our analysis of data on tax disputes between tax authorities shows that the vast majority of high-tax countries’ enforcement efforts are directed at other high-tax countries. In effect, non-haven countries steal revenue from each other while letting tax havens flourish.

This policy failure is reinforced by the incentives of tax havens. By lightly taxing the large amount of profits they attract, tax havens have been able to generate more tax revenue, as a fraction of their national income, than the US and non-haven European countries that have much higher rates. The low revenue-maximising rate of tax havens can explain the rise of the supply of tax avoidance schemes documented in the literature – such as favourable tax rulings granted to specific multinationals – and in turn the rise of profit shifting since the 1980s.

Our findings have implications for economic statistics. They show that headline economic indicators – including GDP, corporate profits, trade balances, and corporate labour and capital shares – are significantly distorted. The flip side of the high profits recorded in tax havens is that output, net exports, and profits recorded in non-haven countries are too low. We provide a new database of corrected macro statistics for all OECD countries and the largest emerging economies.

Adding back the profits shifted out of high-tax countries increases the corporate capital share significantly. By our estimates, the rise in the European corporate capital share since the early 1990s is twice as large as recorded in official national account data.This finding has important implications for current debates about the changing nature of technology and inequality (e.g. Piketty and Zucman 2014, Karabarbounis and Neiman 2014). Our work provides concrete proposals to improve economic statistics and the monitoring of global economic activity.

A live demonstration of the accuracy of a Hellfire or Harpoon in downtown Zurich will bring tax avoidance to a very quick end.

Once Steve Bannon selects a tax law firm, it’s just a matter of time….

Maybe we should invade all those tax havens. I’ll bet we’ll recover our military expenditures very quickly.

Yes! Let’s bring democracy to those countries!

Ooh boy, I needed that laugh, Thanks!

Why not just eliminate corporate income taxes entirely? Instead tax both the wealth and income of the beneficial owners of corporations, the stock and bond holders.

Isn’t that Peter Peterson’s, the Cato Institute’s, the Kochs’, the Heritage Foundation’s, the Chamber of Commerce/Corruption’s preferred policy approach? Yah, let’s have thousands of wealth grabbers to try to chase down and prosecute (while they cooperate to bribe the legislatures to change what’s illegal, and do the dirty with the enforcement bureaucracies to maintain the capture status.)

Personhood has consequences. Gotta pay the piper for all that free speech and limited liability.

I recommend simplifying tax codes and progressively increasing rates to give corporations an incentive to spend. I would penalize more than nominal stock buy backs, excessive exec. comp and so on, and other egregiously anti-social conduct. Related to that is to limit limited liability and make more things undischargeable in bankrcuptcy than just student loans.

It would also make sense to more vigorously use control provisions. For example, a corporation should be deemed headquartered and subject to tax and other jurisidictional claims based on where its principal officers work and make decisions, not in the most convenient secrecy jurisdiction chosen by their tax accountants. Ditto with earnings and taxes, particularly given how much “trade” is intracompany.

The point is to use taxes for what they are designed to do – encourage some behavior, discourage others – rather than simply to reward lobbying prowess.

This phenomenon represents a lack of political will more than anything else IMO. Funds transfers are traceable and can be reconciled with accounting entries by tax auditors. However, with all the gaming of intra-company transfer costs that is going on to minimize reported taxable income in higher tax jurisdictions, why not just tax corporate gross revenues in each country rather than their reported taxable profits? The individuals who own and manage these transnational banks and corporations want all the benefits associated with operating in developed countries without participating in paying for them.

Yes, if we can enforce sanctions on foreign countries for their economic activity abroad, we can certainly enforce the tax code on domestic industry and finance.

As usual, Canada is chopped liver? However, the graph explains a lot about what happened to Puerto Rico. IMHO, SW, LX, IR, and those other guys on the left side of the chart should look out. Can’t go on like this.

Boycotting needs to make a comeback. I see no other reason how corporations will comply.

Wow – very interesting. We’re now starting to quantify the scale of the corporate tax avoidance problem.

My guess is a good portion of these missing profits are related to intellectual property. Many U.S. companies transfer ownership of their intellectual property to a foreign subsidiary. This foreign subsidiary then collects royalties on every sale of the companies products in compensation for the right to use copyrights, patents, and trademarks associated with these products. I think the local subsidiaries which sell these products can deduct intellectual property royalty payments from their taxable earnings, resulting in even less taxable income reported in the country where a sale originates. Strategies like these shift most of the taxable income from a companies worldwide product sales to their foreign intellectual property subsidiary, which resides in a low tax jurisdiction.

The recently passed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act included a token minimum tax on certain types of foreign subsidiary income, but we apparently have a long way to go in addressing this issue.

I’d say their estimations are low, only 40% shifted?

And I disagree with this:

As long as IP is almost impossible to value then tax-avoidance is easy and IP rights are not up to individual countries to decide. International organisations and treaties are keeping the biggest loophole open and they are definitely a by-product of globalisation. TTIP etc….

Let’s call it like it is. This isn’t a matter of policy failures or mistaken policy judgments. This is a matter of corporate criminality aided and abetted by political corruption. The answer lies not in policies but in another “p” word–prisons.

They(US multinational) have been extended the carrot with the reduction in corporate tax rates…time for IRS to brandish the stick ( YO Congress …increase their budget!!!). Theoretically, the decrease in the corporate rate should reduce the incentive of US multinationals to move profits offshore…but there’s still a problem…some of the states still have high corporate tax rates ( e.g. PA’s rate is a just hair under 10%). So a PA corp could still have an effective tax blended federal/state rate of about 29%. Probably still too high for them to cease playing games.

SO IRS will still have its work cut out for it.

BTW …real nice work shining the spotlight by the authors