One of the frustrating aspects of the orgy of “ten years after Lehman” stories is that writers and pundits, many of whom are old enough to have missed the credit excesses that were evident in 2006 and 2007, are now screeching “A crisis is nigh” without necessarily focusing on likely triggers.

As an aside, we are already in the midst of emerging market crises. The IMF agreed to give yet another monster bailout to Argentina. Pakistan is seeking an IMF rescue (or more accurately, trying to get shored up by any one other than the IMF but keeping the agency on the front burner in case other options fail). Turkey is still on the ropes. So calling a crisis is trivial because they are on now.

However, many of these writers are presumably anticipating something more like the global financial crisis, and too often are looking in the wrong places. There is a difference between market crashes that don’t impair the financial system, like the dot-com bust, because the assets that fell in price weren’t highly leveraged. You get real economy damage but not a financial crisis. You can also have lots of loans go bad and not impair the banking system because the credit risk was either well distributed among banks and/or significantly shifted onto investors who losses aren’t leveraged back to the financial system.1

However, one of the sources of systemic risk being overlooked is derivatives. That is particularly worrisome since the crisis was a derivatives crisis, and not a housing crisis, as it is too commonly depicted. Even though the US and other housing markets were certain to suffer a nasty bust, a housing crisis alone would have resulted in something like a bigger, badder saving and loan crisis, not the financial coronary of September and October 2008.

Derivatives allowed speculators to create synthetic exposures to the riskiest subprime housing debt that were 4-6 times its real economy value. Those bets wound up heavily at systemically important, highly leveraged financial institutions like Citigroup, AIG, the monolines, and Eurobanks.

As derivatives expert Satyajit Das explained in a recent Bloomberg op-ed, the big post crisis solution to derivative risk, to force most derivatives to be cleared through central counterparties, hasn’t lived up to its promise. Das cites the example of how a single bad energy futures trade by a Norwegian investor recently blew through most of the NASDAQ’s mutual default fund. Even though this particular loss wasn’t consequential in financial system terms, Das argues that it illustrates how derivative risks are alive and well.

The post crisis remedy settled on in 2009 was to require trades to be cleared through central counterparties who would be the ones to assume the credit risk of buyers and sellers. But as Das and others (including your humble blogger) pointed out then, all this did was to move that risk out of banks and big leveraged financial players like hedge funds, and into the counterparties, which themselves are too big to fail entities.2 And even though it is true that a central counterparty will reduce overall credit exposures, as Das has explained numerous times, there is a big gap between theory and practice.

From a 2016 post:

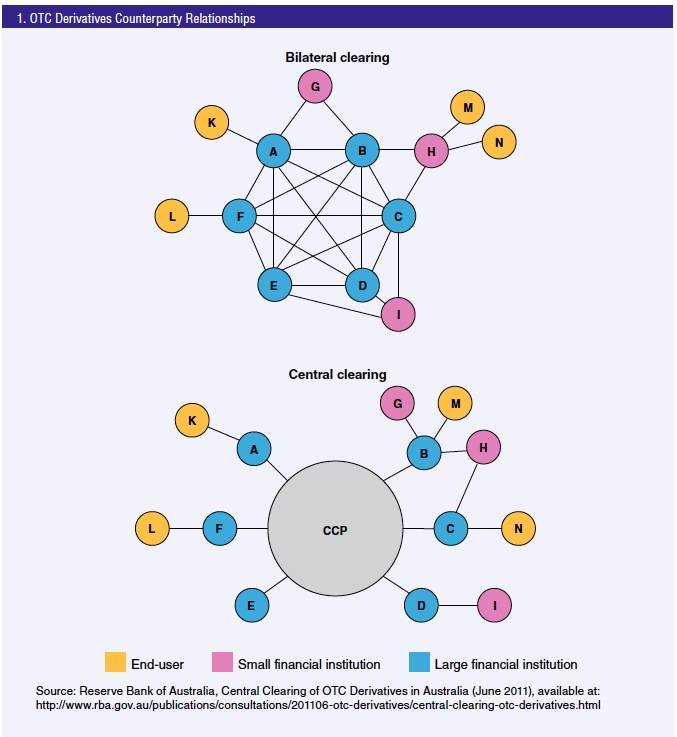

The high concept was that by having dealers all interact with a single counterparty, it would reduce the opacity and complexity of counterparty risk, thus making it easier to manage.* This chart which the Chicago Fed cribbed from the Reserve Bank of Australia illustrates how the world of central clearing is perceived to be an improvement over the old regime:

…..

Shorter: banks that provide critical support to the CCP have their own credit exposures; they can become impaired or liquidity constrained and hence fail as major counterparties or as critical backstops in times of stress.

So the high-level conclusion is that CCPs in theory are an improvement over the old status quo, but they need to be implemented well to achieve their promise. Most important, they need to have strong enough capital buffers. Even then, they are not a magic bullet.

Now aside from [the Financial Times’ John] Dizard’s warning, there was reason to be concerned about the motivation for creating central counterparties, in that it was to reduce the “too big to fail” problem. In other words, given the limited, conditional risk reduction that would result, the idea of moving more credit risk to central counterparties was more than anything else to solve a political problem: to get the government out of the liquidity provider of last resort game. If you look at the chart above, those little blue circle in the first chart would be banks that would almost certainly get government support, particularly given that the authorities have allowed banks to use taxpayer deposits to fund derivatives exposures. By contrast, the central counterparty is in theory a more robust entity and does not have direct access to the government drip feed.

But an inadequately capitalized CCP is just another “too big to fail” entity. And since the CCPs are private, there would be motivation for the participants to have the CCP be underresourced, since higher margins mean higher transaction costs and therefore lower trading volumes. And although no one would admit to this, bankers know full well that no financial regulator is willing to let markets seize up in our brave new world of market-based credit, as opposed to bank-loan-based credit.

Das flags four problems with the central counterparty regime:

First, oversight is fragmented….

Second, the system assumes traders can meet margin calls at short notice…In practice, volatile market conditions require higher margins, which exacerbate systemic cash needs, force mass liquidation of positions and increase the central counterparty’s risk.

Third, initial margin-setting relies on risk models — based on assumed price behaviors and historical volatility and correlation data — that have repeatedly failed in the real world….the ability of non-defaulting members to bear losses may be lower than expected. Even single counterparty limits, designed to avoid concentrated exposure, are imperfect, as Norway’s case highlights.

Fourth, central counterparties have adverse incentives. To gain market share, they might undercut each other on margins or default fund contributions, thus undermining the stability of the system itself. The default waterfall also entails moral hazard: Strong firms, forced to bear the liabilities of the weak, have little motivation to become clearing members.

Thees is a small bit of good news. As the Financial Times’ John Dizard described earlier this year, the “derivative” that desperately needed to be slowly strangled, the unregulated insurance misnamed as a credit default swap, is becoming more feeble all on its own. As Dizard wrote in Time to wipe out the absurd credit default swap market:

There was a time when the credit default swap market was a giant, incomprehensible and terrifying threat to the global economy…..Now it is a gigantic, incomprehensible global joke…

At least back in 2008, dealing in CDS was sinister or arcane. Now it just seems pointless, what the American military calls a “self-licking ice-cream cone”….

The CDS business is still big but at a time when most markets have been growing (or just inflating), it has been steadily shrinking in notional size. According to the Bank for International Settlements, the notional value of all CDS has declined from about $25tn at the start of 2013 to less than $10tn today.

Even a $10tn black hole could terrify editorialists, policymakers and conference attendees. It has become apparent, though, that most of that is helium in the balloon. Those trillions could only end life as we know it if someone (taxpayers, depositors, investors) had to pay them to someone else (foreign billionaires, Bond villains, New York and London socialites).

With ever-greater frequency, though, CDS participants are being told by the authorities or “determination committees” of market participants that we were just kidding, no one takes this seriously any more. I am inclined to agree with this de-escalation policy, but the problem is that some less knowing market participants may believe the “protection” offered by CDS represents a genuine hedge against risk, which could result in some significantly unbalanced books when there is another global financial crisis….

Can anyone find a way to bury this absurd pseudo-market?

While somewhat reassuring, this development seems to prove out the theory that regulators (or this case, self-regultory bodies) are good at fighting the last war, so a new crisis is unlikely to look much like the one just past. And if anyone were serious about curbing derivatives trading, there’s a simple remedy: a transactions tax. But making that work would require a great deal of international cooperation, and too many financial centers would rather assist their local champions rather than prevent the next bust.

_____

1 That sentence is a bit heavy on finance lingo, so let’s unpack a bit by using a case study. In the 1980s, raiders funded leveraged buyouts using junk bonds and loans. The loans were syndicated, with JP Morgan as the dominant syndicator retaining only a teeny piece and enlisting deep pocket obliging chumps like Japanese banks to provide the funding.

The LBOs in the later 1980s were typically and obviously terrible, but ginormous up-front fees (like $30 million out of a $500 million loan on the Campeau deal) made the banks, which often had bad internal incentives regarding how they treated those fees, kept the money flowing longer than it should have.

So even though many of those loans came a cropper in the nasty early 1990s recession, they didn’t create a financial crisis because the loans were widely held and because they were worked out in most cases, meaning the losses weren’t 100%. One can imagine that bank regulators were awfully permissive in how they allowed banks to value the loans while retructurings were in progress.

By contrast, in the financial crisis, quant and global macro hedge funds would be hit by losses due to wildly gyrating markets. Those trades were often leveraged, as in done on margin. These traders were often forced to liquidate position, or they might dump an asset in completely different market (say gold) that was OK shape to avoid recognizing a big loss on the trade being hit with a huge margin call. The result of dumping either position (in the crashing market or the one that was less afflicted) would be to cause a price move that could then lead other margined players to have to meet margin calls and potentially liquidate positions. If a hedge fund failed (and recall many did, investors who could would also pull out cash, forcing even more liquidation) would deliver losses to exchanges and/or bank lenders. And the investors in those funds might have been levered themselves…

2 Note that exchanges combine transaction-matchign with clearinghouse functions. As we wrote in 2009:

…the cheery view of the safety of exchanges is based on the airbrushing out of a near failure. In the 1987 stockmarket crash, a large counterparty of the Chicago Merc had failed to make a large payment by settlement date, leaving the exchange $400 million short. Its president, Leo Melamed, called its bank, Continental Illinois, to plead for the bank to guarantee the balance, which was well in excess of its credit lines. The officer in charge said no,. It was only because the chairman walked in and authorized the backstop only three minutes before the exchange was due to open that the Merc kept going.

Melamed has said repeatedly that if the Merc did not open that morning, it would not have opened again, and the head of the NYSE has said if the Merc did not open that morning, the NYSE would not have either, and it might never have repoened either.

Remember that. One decision with three minutes to spare kept the two biggest exchanges in the US from collapsing in the 1987 crash. See Donald MacKenzie’s An Engine Not A Camera for details.

Bankers only have one real product and that’s debt.

When they are messing about you can see it in the private debt-to-GDP ratio.

It’s that simple.

They are clever and hide what they are doing on the surface, you just look underneath.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

The S&L crisis can be seen, but it’s very small because it isn’t leveraged.

Leverage is just a profit and loss multiplier.

The bankers take the bonuses on the way up and taxpayers cover the losses on the way down.

“It’s nearly $14 trillion pyramid of super leveraged toxic assets was built on the back of $1.4 trillion of US sub-prime loans, and dispersed throughout the world” All the Presidents Bankers, Nomi Prins.

Jim Rickards looked at the data after 2008:

Losses from sub-prime – less than $300 billion

With derivative amplification – over $6 trillion

The bankers called an insurance product a Credit Default Swap to fool the regulators.

The regulators are still fooled after this caused such trouble in 2008.

Wall Street is moving its swaps to Europe due to the lax regulations.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xT-tie8sFog&feature=em-uploademail

Paul Volcker’s contribution towards the end of the video is quite amusing.

Thank goodness for the 1033 Program!

Merc-istan…my first direct taste of “allocation” of capital while living in Chicago… Someone reminded me this week that my secret sauce with getting fed regulators to somewhat enforce the CRA lending requirements was to point out how “underwriting” requirements are nebulous by pointing out the magic merc accounting rules and subsequent fake and shake leading thru the s&l crisis…as Madame Leona reminded us…

Rules are for das little people…

and “justice”… Well…most people forget justice has its root in Latin. And once you realize what it has always “meant”…then one might understand moi gives not a (family blog) about “social justice” and all that counts is victory…

So I guess us unwashed (in the blood of the All-Holy Market) mopes who have all along felt and said that derivatives are the Spawn of the Devil and just another Sword of Vulnerability hung over our ungarnished heads, get to say “WE TOLD YOU SO?” And that “notional value dollars” in fact are real ‘exposures,” not just in the sense of “being exposed to risk,” but in the sense of “exposing to the view of anyone who cares to look, the moral and practical bankruptcy of the FIREplace,” maybe had the right of it?

Not that such awareness has been coupled in any way with the power to affect or effectuate policies, as against the Massive Wall of Greed and Generic Shrugs of Indifference or Prostrations of Futility.

How many people will read this post, and garner any useful awareness out of this esoterical miasma of money creation and injection as to what could be forced to be done? Short of awaiting a crash, bowing our shoulders like good draft animals, and laboring one again to refill the Real Wealth pot for these effing vultures and tapeworms to swoop in and slurp up yet again?

Tell me again why the debasement of mostly the soon-to-be-not-the-world-currency-any-more Dollar via this casino actually straight looting) behavior is not accurately described as COUNTERFEITING? Injecting essentially “notionally” worthless QUADRILLIONS of dollars into the political economy? To do things that are totally “socially useless” but which pay huge dark and black fees and paper profits, risk-free to the intermediaries? Like the Empire and other players in the Great Game have repeatedly done to Enemies “that it’s OK to debase their currencies because TOTAL WAR and all that? Well, the debasers are doing this stuff with legitimizing blessings from “our” government, and who the hell knows, in this vast power game, whether maybe one of the Alphabet Agencies or a set of them are involved in creating and facilitating all this? Since these are great sorts of transactions it would seem to me, to hide all kinds of “off budget” shenanigans and evils? As well as “moving fast and breaking things” out of which activities the powers that actually be can reap still more power and looted and purloined wealth? And one wonders at the interlocks and overlaps between the people that create and extend this “market activity” and the lists of those who actually have their hands on all the levers of power…

What kind of political economy do “we” want, again? What organizing principle(s) do “we mopes” want that political economy to function under and respond to and further? A tiny few of “us,” of the species, are dictating and manipulating the operations and outcomes of the thing, the vast complexity, that gets labeled “the political economy.” Other than waiting for shoes (and boots) to fall, what are and what can any of us do to change the vector and momentum and inertia of it all?

Thanks for cutting through the irrelevant and unimportant for us. Much appreciated.

I can’t help thinking that the above occurrence might have been the solution to the problems of financialization and all its crises and risks, but I’m sure there will be a rebuttal as finance (profit) is King right now and everyone else is subject to that king. We would have a far, far better world if labour (people) were dominant over capital instead of capital being dominant over labour (people).

Thanks for this post. Brooksley Born* saw the dangers in the unregulated derivatives market and tried to get it regulated. She was stopped by the Clinton admin. She saw all of this coming.

The derivatives market is still unregulated. To me, this unregulated derivatives market looks like an excellent extortion mechanism against govts; that works to the benefit of the FIRE sector (we’re so cross-connected and unregulated the govt has to bail us out, or else) and against the public. But I’m not an economist.

*https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/warning/interviews/born.html

adding, from the pbs link:

As head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission [CFTC], Brooksley Born became alarmed by the lack of oversight of the secretive, multitrillion-dollar over-the-counter derivatives market. Her attempts to regulate derivatives ran into fierce resistance from then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, then-Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and then-Deputy Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, who prevailed upon Congress to stop Born and limit future regulation.

No wonder Rubin et al are making the rounds talking about what a “great” job they did managing the crisis. They have a lot to answer for, imo.

adding: Bill Black on deregulation leading to the crisis. (part 1)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVVfuMRqE9c

Great post – thanks. Good to hear that the CDS market is on the downswing. I still have to wonder though, considering that owning a CDS but not the underlying asset is similar to buying hazard insurance on your neighbor’s house, why is this even legal in the first place? And I’m not so sure that the underlying assets, ie a bunch of chopped up and repackaged mortgages, should be legal either. There is just too much room for fraud in something like that.

Banks should hold and service the mortgages they originate, not just create a bunch of dubious Alt-As and sell them off to be someone else’s problem. If they aren’t willing to do that, then the government can step in. Why do Freddie and Fannie have to be quasi-government agencies, where the private sector gets the gold and the government gets the shaft when things turn south, and not the real thing?

Oh, I forgot, because capitalism.

There are some banks that make and hold loans. All of us should be doing business with them. One simply needs to ask, “Are you strictly a portfolio lender?”

My guess for why such gambling contracts remain untegulated. Lawyers on the whole are largely financially innumerate. Those that aren’t largely act for the financial institutions that created CDS in the first place. By swathing the derivatives contracts in financial jargon the developers successfully hid the underlying realities from the majority of lawyers (and politicians). Hence they remained largely unregulated.

Thanks for such an interesting article. I certainly learnt a lot from it.

Yves:

Wall Street was supposed to establish a Clearing Board for Derivatives, In all of their irrational exuberance of passage of Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act which Senator Dorgan spoke out against and prescient Brooksley Born of the CFTC warned unfettered derivatives; Wall Street did not do so. The market would take care of itself. It didn’t and Main Street paid the check for Wall Street.

Reserves, taxation, clear ownership of CDS and its counter, and regulation would go a long way. Increasing the limit to $250 billion for banks let more of the ones who should be watched closely into the hen house. Deutsches is already in trouble. The limit should not have exceeded 50% of the new boundary. And Dems supported this move.

The Fed’s fleet of choppers only flies over Wall Street and the Pentagon, so why not also give the Fed full, unconditional responsibility for the CCPs and regulating derivatives? Following the Bernanke Fed’s massive subsidized loans, asset purchases, and QE programs; the government’s coordinated suppression of Occupy; and the Obama administration’s TARP program and failure to enforce criminal law; it appears that prudent underwriting and risk management have gone the way of the buffalo. Why not make it all explicit? But let’s not call it capitalism.