Yves here. Note that Lambert wrote about witch hunts as a tool of social control in 2015.

By Peter T. Leeson, Duncan Black Professor of Economics and Law, George Mason University. Originally published at VoxEU

President Trump frequently refers to Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into possible Russian collusion during the 2016 presidential election as a ‘witch hunt’. This column argues that competition might be behind both this current ‘witch hunt’ and Europe’s ‘witch craze’, which between 1520 and 1700 claimed the lives at least 40,000 people. Today it is competition between Democrats and Republicans; in 16th and 17th century Europe, it was competition between Catholicism and Protestantism in post-Reformation Christendom.

‘Witch hunts’ – the search for evil forces, real or imagined, so that they can be expelled or destroyed – are a recurring theme in Western history. Today, scarcely a day seems to pass that President Donald Trump or one of his defenders does not refer to Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into ‘Russian collusion’ regarding the 2016 US presidential election as a ‘witch hunt’ (Paschal 2018). Four hundred years ago, scarcely a day seemed to pass that someone in Western Europe was not hunted and prosecuted by authorities for being an actual witch. Surprisingly, the force responsible for both witch hunts may be the same: competition.

Popular opinion has long held that Europe’s ‘witch craze’, which between 1520 and 1700 claimed the lives at least 40,000 people and prosecuted twice as many, resulted from bad weather. Not without reason: European witch hunting overlapped with the ‘Little Ice Age’. During this period, dropping temperatures damaged crops and thus citizens economically, and disgruntled citizens often search for scapegoats – in the 16th and 17th centuries, literal witches. Emily Oster’s (2004) research was the first to investigate this hypothesis empirically. Using data on witch trials in 11 European regions between 1520 and 1770, her study found support for the bad-weather theory.

But could Mother Nature-induced misfortune, such as that resulting from bad weather, really be responsible for Europe’s witch craze? Crop failures, droughts, and disease were hardly unknown in Europe before the witch craze. In the early 14th century, for instance, the Great Famine decimated populations in Germany, France, the British Isles, and Scandinavia; yet there were no witch hunts. Further, while weather could not have varied dramatically between neighboring locales in 16th and 17thcentury Europe, the number of people prosecuted for witchcraft often did.

In a recent paper, Jacob Russ and I hypothesise a different source of historical Europe’s witch hunts: competition between Catholicism and Protestantism in post-Reformation Christendom (Leeson and Russ 2018). For the first time in history, the Reformation presented large numbers of Christians with a religious choice: stick with the old Church or switch to the new one. And when churchgoers have religious choice, churches must compete.

One way to deal with competitors is to ban them legally; another is to annihilate them violently. The Catholic Church tried both approaches with its Protestant competitors but had little success. Within just a few short years of Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses, too many citizens, and still more important, rulers in Christendom had already become converts. Outside of Catholic strongholds, such as Spain, Italy, and Portugal, many rulers proved unwilling to suppress Protestant competition with inquisitions.

The Church thus had to take another tack to maintain its market share. The one it took is unsurprising given then-popular belief in witches, and was quickly emulated by its Protestant rivals. In an effort to woo the faithful, competing confessions advertised their superior ability to protect citizens against worldly manifestations of Satan’s evil by prosecuting suspected witches. Similar to how contemporary Republicans and Democrats focus campaign activity in political battlegrounds during elections to attract the loyalty of undecided voters, historical Catholic and Protestant officials focused witch trial activity in religious battlegrounds during the Reformation and Counter-Reformation to attract the loyalty of undecided Christians.

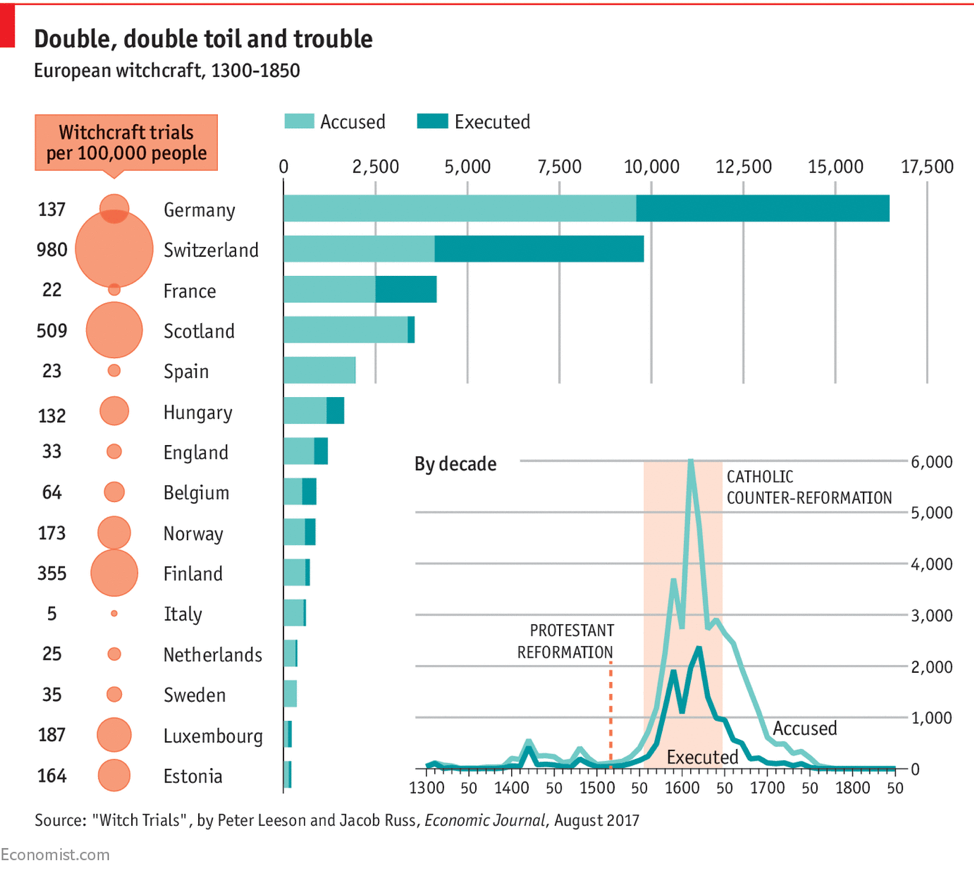

Analysing new data that contain more than 40,000 suspected witches whose trials span 21 European countries over the course of more than half a millennium (1300-1850), Russ and I find that when and where confessional competition, as measured by confessional warfare, was more intense, witch trial activity was more intense too. Bad weather, in contrast, has no relationship with witch trial activity.

Figure 1 European witchcraft, 1300-1850

Our data reveal that the witch craze took off only after the Protestant Reformation in 1517, following the new faith’s rapid spread. The craze reached its zenith between c.1555 and c.1650, years coextensive with peak competition for Christian consumers, evidenced by the Catholic Counter-Reformation, during which Catholic officials aggressively pushed back against Protestant successes in converting Christians throughout much of Europe. Then, around 1650, the witch craze began its precipitous decline, prosecutions for witchcraft virtually vanishing by 1700.

What happened in the middle of the 17th century to bring the witch craze to a halt? The Peace of Westphalia, a treaty entered in 1648, which ended decades of European religious warfare and much of the confessional competition that motivated it by creating permanent territorial monopolies for Catholics and Protestants – regions of exclusive control, wherein one confession was protected from the competition of the other.

The hypothesis that Russ and I propose also predicts that the witch craze should have been focused geographically, located where Catholic-Protestant rivalry was strongest and vice versa. And indeed it was. Germany alone, which was ground zero for the Reformation, laid claim to nearly 40% of all witchcraft prosecutions in Europe. In contrast, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Ireland – each of which remained loyal to the Church after the Reformation and never saw serious competition from Protestantism – collectively accounted for just 6% of Europeans tried for witchcraft.

Perhaps the ‘witch hunts’ that President Trump now claims he and his associates are subjected to reflect a similar, competition-driven phenomenon. Frustrated with the fact that Trump won the presidential election, and desiring but unable at this juncture to impeach him, Democratic Party leaders are encouraging another approach: dig for ‘dirt’ on Trump and his associates that can get the job done. If nothing comes up, at least the electorate will be convinced of their commitment to ‘rooting out evil’, providing a leg up against Republicans in the next election.

There is also this parallel: not only did the Catholic Church mostly avoid conducting witch trials until it faced religious market competition in the 16th century, until the turn of the fifteenth century, it denied the very existence of witches. Perhaps similarly, Democratic Party leaders who are now certain that ‘Russian witches’ are casting spells on American politics decried Joseph McCarthy’s ‘witch hunt’ in the 1950s and denied the existence of ‘red witches’. Even the existence of witches, it seems, is influenced by competition.

See original post for references