By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street

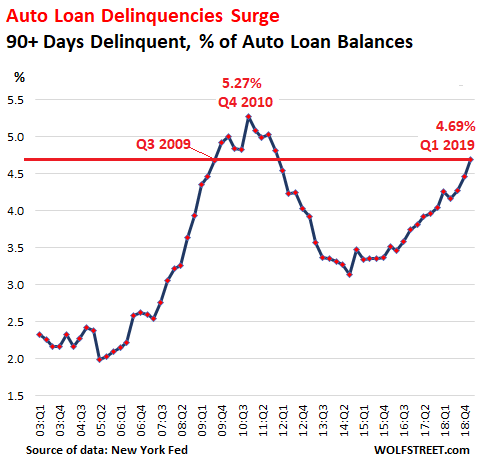

Serious auto-loan delinquencies – 90 days or more past due – jumped to 4.69% of outstanding auto loans and leases in the first quarter of 2019, according to New York Fed data. This put the auto-loan delinquency rate at the highest level since Q4 2010 and merely 58 basis points below the peak during the Great Recession in Q4 2010 (5.27%):

These souring auto loans are going to impact banks and specialized lenders along with the real economy – the automakers and auto dealers and the industries that support them.

This is what the banks are looking at.

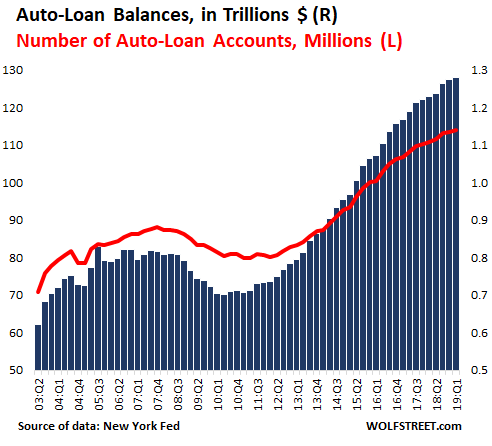

The dollars are big. In Q1, total outstanding balances of auto loans and leases rose by 4% from a year ago to $1.28 trillion (this amount by the New York Fed is slightly higher than the amount reported by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors as part of its consumer credit data). Over the past decades, since in Q1 2009, total auto loans and leases outstanding have risen by 65%.

But the number of auto-loan accounts has risen only 34% over the decade, to 113.9 million accounts in Q1 2019. In other words, what caused much of the increase in the auto-loan balances is the ballooning amount financed with each new loan and longer loan terms that causes those loans to stay on the books longer.

The chart below shows the dollar amounts of auto loan balances (blue columns, right scale) in trillion dollars and the number of auto-loan accounts (red line, left scale) in millions:

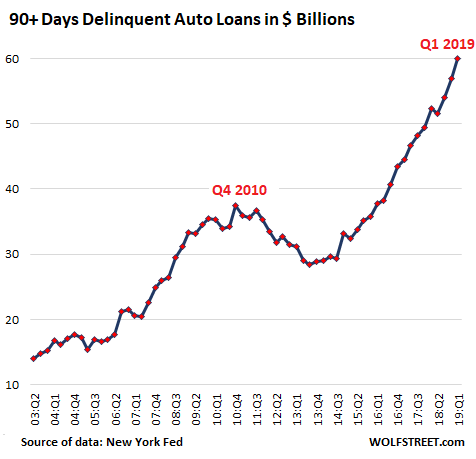

Of this ballooning amount of auto loans, 4.67% is seriously delinquent (90+ days). This amounts to $60 billion. This chart shows the trajectory of what the banks and specialized lenders are facing, in billion dollars:

For lenders, these delinquent loans don’t represent total losses. This debt is collateralized by vehicles, which can be repossessed without much of a delay – unlike foreclosing on a house. But generally, the loan amount is far higher than what a repossessed vehicle will bring at the auction. Perhaps the banks can recover 50% on average of the loan amount. So, if all of the current vintage of 90+ day delinquencies turn into repossessions, and the banks lose 50% on them, it would amount to $30 billion in loan losses.

But there are more loans going delinquent even as we speak, and they will become seriously delinquent in Q2, and the next batch in Q3, and so on, and this is working itself forward wave after wave. So the cumulative losses over the next two years will be higher.

These losses are spread over thousands of banks, credit unions, and specialized non-bank lenders, and over asset-backed securities holders, such as pensions funds, other institutional investors, and bonds funds, and most will get through this by just licking their wounds. But some smaller subprime-focused non-bank lenders will collapse, and a few have already collapsed. So these defaulted auto loans are going to hurt, and they’re going to take down some smaller lenders, but they’re not going to take down the US banking system. They’re just not big enough.

This is what automakers are facing.

Lenders have already figured out that subprime auto loans have soured. They’ve been seeing this since 2015 or 2016. And ever so gradually, lenders have tightened their subprime underwriting standards. And subprime customers that don’t get approved for a new-vehicle loans may get approved for a much smaller loan for a cheaper used vehicle. This process has already been shifting potential new-vehicle customers to used vehicles.

For automakers, this has already shown up in their sales. New-vehicle sales, in terms of vehicles delivered to end-users, peaked in 2016 and have been declining ever since. Through Q1 this year, new-vehicles sales, fleet and retail, were down 3.2% from Q1 2018, and so 2019 looks to be another down-year for the industry – the third in a row.

But this isn’t happening in a recession with millions of people losing their jobs and defaulting on their auto loans because they lost their jobs. This is happening during one of the strongest labor markets in many years. It’s happening when the economy is growing at around 3% a year. It’s happening in good times. And people with jobs are defaulting.

This is not a sign of a worsening economy, but a result of years of aggressive and reckless auto lending, aided and abetted by yield-chasing investors piling into subprime auto-loan backed securities because they offer a little more yield in an era of central-bank engineered financial repression. It’s a sign like so many others in this economy, that the whole credit spectrum has gone haywire over the years. Thank you Fed, for having engineered this whole thing with your ingenious policies. So now there’s a price to pay – even during good times.

And we already know what a scenario looks like when the cycle turns, when unemployment surges and millions of people lose their jobs and cannot make their car payments, even people with a prime credit rating – that will then turn into subprime. We know what happens to the auto industry when the economy dives into a recession. We know what this will look like because we’ve seen it before. The auto industry is very cyclical.

What we haven’t seen before is this kind of credit stress among car buyers during good times – with the bad times still ahead. So when credit stress gets this bad during good times, we don’t even want to imagine what it might look like during bad times. Whatever that scenario will be, it won’t be fun for automakers.

The surprise was in the SEC 10-Q filing when no one was supposed to pay attention. Read... Tesla Discloses Record Pollution Credits for Q1: Without Them, it Would Have Lost $918 Million and Bled $1.14 Billion in Cash

Sub-prime auto loans.

What could possibly go wrong?

Oh yeah, I remember now.

A haiku?

During “good times” … ? I think we need a new definition of what constitutes “good times.” Using GDP and the stock market as indicators of the health of the economy is bogus. They are rather indicators of the economy for the 1% and do not say much about the economic health of the entire population..

Exactly. Look to the shrinking share of productivity gains going to labour as wages as the source of the problem. That’s why there’s sub-prime lending in the first place.

Good point.

Subprime wage growth relative to productivity directly leads to a requirement for subprime lending to ‘finance’ growth.

Two reasons for this: (1) Auto dealers lie about customers’ incomes and (2) this is NOT a strong labor market. Everyone knows the employment/unemployment numbers are false.

Good point. In addition, if the labor market is so tight why are wages not increasing?

re: Everyone knows the employment/unemployment numbers are false.

how so?

Are we going to have to bail these a-holes out again? They don’t even make cars anymore and a Chevy Silverado costs $65,000 while being built in Mexico. It is like the U.S. carmakers want to go out of business.

This is not a sign of a worsening economy, but a result of years of aggressive and reckless auto lending, aided and abetted by yield-chasing investors piling into subprime auto-loan backed securities because they offer a little more yield in an era of central-bank engineered financial repression. It’s a sign like so many others in this economy, that the whole credit spectrum has gone haywire over the years. Thank you Fed, for having engineered this whole thing with your ingenious policies. So now there’s a price to pay – even during good times.

This is hardly a problem for the banksters, but woe be to the car buyers. Cars have gotten way too pricey, imo

History doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes….

On the delinquent loans, just one clarifying (I hope) comment: these data I am pretty sure are for ALL car loans. New AND USED. Remember that while 17 mm new cars transact each year, another 40 mm used cars change hands, with lots of loans attached. This does not mean that the problem is any less severe or that any of the authors’ points are invalid, only that the article seems to imply (hedge, hedge) that this is all about “the car companies” getting themselves into trouble again. Most, I would hazard, of the worst delinquencies are in the USED CAR side of the equation: low-income people getting upside-down in subprime loans on used cars. Again, that does not invalidate any point in the posting, but I am trying to assert that even if every OEM and every OEM captive finance company and every bank financing new-car sales changed the way they did things, a big part of this problem would still remain, in the used side. “The media” in general tends to focus on the new-car industry, but the average age of a new-car buyer is now 54. Most of the rest of us are buying used. THE USED CAR INDUSTRY IS IN REVENUE TERMS ABOUT THE SAME SIZE AS THE NEW-CAR INDUSTRY. Loan and credit issues in used are generally WORSE than they are in new.

Two issues here, one, 6 and 7 year car loans put people in more expensive loans longer ago, incentivizing new vehicle purchases, and two the collateral damage to a used car repo is less than that in a new purchase repossession as the used dealer can probably recover more, and indeed likely in some cases that’s part of the biz model, and sell the same car several times, while the new purchase goes to auction and takes a big depreciation. I’m no expert but I think these things need to be considered.

I agree. Certainly as a car ages the absolute annual depreciation hit reduces (though in percentage terms it may be stable): a 15-year-old $1,000 clunker has not much room to fall. And yes, at the very low end of the market (Joe’s Used Cars, gravel lot, etc.) the dealer actually doesn’t really care much about the CAR at all, she or he is selling FINANCING. Typically for such a dealer the interest rate may be 10% and the loan default rate 15%, so it is all about managing payments and repos… if the car loses $200 in value, heck, as you put it, just sell it again. (Loan defaults are high because incomes are low and recourse is weak: if someone on minimum wage defaults on a car loan, it is hardly worth the effort to sue them: what else have they got you can take?) If you follow a purchase at one of these lots you can see it happening: the customer STARTS with the finance officer, and then, once the loan is set, they go look at the cars. At a new car dealer it is reversed: pick out your car, now let’s see if we can get you financed.

But since GM Financial does loans for both new and used cars, I’m not sure I understand what the practical effect is of taking the used car market into account? The car companies are still getting themselves into trouble, aren’t they?

You are of course correct, but the captive finance arms actually have a much smaller share of the used market than of the new market. Again, as I said in my comment, the Richter post is entirely correct, and yes, even after taking into account the used market, the car companies are still getting themselves into trouble. Agreed. But when one reads the original Richter post one (I think) gets the impression that this issue is entirely about car companies and their dealers, and leaves out the OTHER players involved. For example, there are 18000 or so new-car dealers and over 30000 USED car dealers, and the latter are very often financed by entirely different sources than the captives. And we haven’t even mentioned the BHPH (buy here pay here) subset of the independent dealers, which NO captive finances, and to which low-income people are the most exposed. So for example if we had a “mild” recession low-income loans might very well implode, with lots of fall-out of course, while the car companies and their captives might not even notice. In a deep recession of course everyone gets dragged in. I was only trying to point out that the new and used markets are not one unitary market. For example, credit scores for NEW buyers have risen every year for the past four years (Experian data), which is not the impression (I think) one might get from the original article. These details get lost when one blurs all 57 mm sales into one large blob. The two markets a) do not move in lockstep (although of course intricately interconnected) and b) are not controlled to the same extent by the OEMs.

The tinfoil hat wearing cynic in me wonders if the government will focus it’s ‘bailing out’ abilities on the automakers that make vehicles for the military? Perhaps it’s time to consider ‘spinning off’ the military vehicle divisions into a State owned entity. Call it, oh, ‘War Corp LLC.’ In the spirit of the times, make it a ‘Public Private Partnership,’ but limit the ability of the “Privates” to own shares to those who can prove incomes in the top ‘One Percent.’ What’s next, Private Armies? Oh, wait. Betsy’s brother….

Mercenaries Я Us?

Just a random thought on those bad loans. I wonder if it would serve a useful purpose to break out and determine whether the actual cars are EV or gas driven cars. That may or may not give an interesting slant on those loans as a self-standing data point.

EV sales (PHEV+BEV) are currently running about 2% of the total new-vehicle sales. Data from California (where about half of all EVs are sold) shows average household income of EV buyers being higher than that of gasoline-car buyers. Average household income in the USA is about $60,000; of new-car buyer households about $100,000, and of new-EV-car buyer households over $150,000. (For more detail, Tesla Model 3 average household income is around $125,000; S, $160,000.) So, my GUESS is EV buyers are much less credit-stressed than gasoline-car buyers, at least so far. Separately, one reason new-car buyers are much better off than the average household is that new-car buyers are OLDER. The average age of someone buying a new car is around 53 or 54 (source is IHS Markit Polk). Older, more established households. Through 20s 30s and even 40s the average American is buying a used car.

If we were to follow the collapse playbook of a decade ago, around 12 million people get their jalopies foreclosed on, with well connected financial major major major majordomos buying up the cars for a pittance, and then renting them out to prospective Uber & Lyft drivers, yeah that’s the ticket.

This is just anecdata, but I’m wondering if anyone else’s memories line up with mine.

When I was young (several decades ago, in the 80s), I vaguely remember car commercials offering terms (possibly lease, probably purchase, though I don’t remember exactly when auto leases became popular) mostly in the ranges of 24 – 36 months. That range sticks strongly in my head, likely due to the significant amounts of TV I watched back then. Nowadays, it’s generally 48 months, with a creeping majority of ads advertising 60 month terms. Just recently, I heard a radio ad pushing 72 month (6 YEARS) financing, which was a shock to me.

I relay this because I find that car loan/lease terms (in the aggregate) are good indicators for the slow erosion of the purchasing power of regular folks. If wages had kept up with life in general, the terms would mostly be the same: 24 – 36 months to pay off a car in 1980 would be the same 24 – 36 months to pay off a car in 2019, even as prices had risen. And yet, terms lengthen while my wallet does not.

However, I haven’t found a good repository of data for the average length of car loan terms over the years. I’m sure it’s out there, but I’m at a loss for how exactly to DDG (or Google) it; I’ve tried, but I get a bunch of extraneous garbage. Gov sources would be great, but there are so many different silos of data that it’s daunting. Would anyone here know if this exists, and where it would be?

Or, just as depressing (and likely), are my memories failing and lying to me?

From Edmunds: “The most common term currently is for 72 months, with an 84-month loan not too far behind. It’s been creeping up: 10 years ago, the most common new-car loan term was 60 months, followed closely by 72 months.

Loans for used cars are about as long: The most common term for a used car in 2018 was 72 months. Even though people are financing about $10,000 less for used cars than they do for new cars, it takes them roughly the same amount of time to pay off the loan.”

https://www.edmunds.com/car-loan/how-long-should-my-car-loan-be.html

I would be interested in finding out how much of the money paid on a 72 month new car loan goes to the car manufacturer and how much ends up in the pockets of the financial industry.

Maybe if Biden gets elected the problem of defaults will be handled by making car loan debt impossible to default on:-)

Wow. 84 months. That’s insane. Pretty soon, you’re going to start seeing car/home mortgage bundles being offered by the banks. Keeps monthly payments down, and you on the hook in perpetuity.

Thanks for the link. It’s still weird, though: I click to Edmunds, which states:

That statement is itself unsourced, and I’m curious where they got it from. The only other worthwhile link on that page is one to a research firm’s news page, which states:

The second quote comments obliquely on the first, in my opinion; why hold on to a car until the last possible moment unless you really don’t want to tack on a monthly car payment? Just from my experience, I had to jump into a lease (60 mos.) when my 15 year old car started breaking down, and was due for more repairs than it was worth…while I like having a new car that is rock solid, I would have preferred to avoid the note.

Where is the source data coming from? There are a ton of data sets at the US Dept of Commerce website, and a ton of data at the Bureau of Economic Analysis (also Dept of Commerce). Several news reports of the average age or duration of loans, but they’re all referencing either Edmunds or Experian. Source data has to be out there somewhere, but I certainly can’t find it.

For vehicle age I can give you an answer as to data source. IHS Markit a few years ago bought a firm called Polk. Polk “scrapes” vehicle age data by extracting it from state DMV records, which are about as good a source as one can get, since the states are very eager to keep tabs on vehicles, so that they can extract registration fees. And when you register your car, they see its age. On the loans I have a less certain answer, but that the data comes from the credit bureaus: Experian, Transunion, Equifax, etc. Because NO lender (of any kind… captive, bank, credit union, etc.) makes a car loan with pulling the credit report (and notifying the CB as to the terms of the loan). So Experian adds up all the loans and leases etc. and aggregates the data, That’s one source of the data. The other source (e.g. when you see Federal Reserve as the source) is from the US government directly pulling data from banks, as banks must report such data to the Fed. The two sources SHOULD align but often do not. For example, often the government data relates to ALL car loans, while the credit bureaus often (not always!) split new and used.

There is much debate about increasing loan terms. “Anti’s” say it is just lenders trying to generate business by lowering monthly payments by making loan terms ridiculously long. “Pro’s” point out that improving car quality means cars last longer, and so why not lend longer terms in response? Indeed, ownership periods have lengthened: in the 1960s the average new car buyer ditched the car in 2 years; now it is 6 or so. MY belief is the answer is somewhere in between. Heck, house mortgages are 30 years and no one yells about that! (grin) With the average age of a single-family home in the USA being about 35 years and the average age of the car fleet at 12, you’d expect ceteris paribus car loans to be 1/3 the length of house loans. (Of course I am partly joking, because many houses appreciate in value and most cars depreciate in value, but just trying to make the point.)

OEM captive finance arms have about half of the new-car financing market, so about half of the loan payments go to the OEMs, and half to external banks … and credit unions, which are often overlooked but whose share has been growing. Data source: Experian.

That is a shockingly long time, and it probably is indicative of reduced real purchasing power, which we already knew was happening.

But it’s hard to do an apples-to-apples comparisons with US cars since the quality has gotten so much better over time. I am going to guess that the average 1980 Chevy Malibu had a lot shorter life than its 21st century counterpart.