By Kate O’Neill, Associate Professor, Global Environmental Politics, University of California, Berkeley. Originally published at The Conversation

Less than two years after China banned most imports of scrap material from abroad, many of its neighbors are following suit. On May 28, 2019, Malaysia’s environment minister announced that the country was sending 3,000 metric tons of contaminated plastic wastes back to their countries of origin, including the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. Along with the Philippines, which is sending 2,400 tons of illegally exported trash back to Canada, Malaysia’s stance highlights how controversial the global trade in plastic scrap has become.

Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam are all halting flows of plastics that once went to China but were diverted elsewhere after China started refusing it. They are finding support from many nations that are concerned about waste dumping and marine plastic pollution. At a meeting in Geneva in May 2019, 186 countries agreed to dramatically restrict international trade in scrap plastics to prevent plastics dumping.

As I show in my forthcoming book, “Waste,” scrap material of all kinds is both a resource and a threat. The new plastics restriction allows less-wealthy countries to exercise their sovereign right not to accept materials they are ill-equipped to handle. This narrows options for wealthy countries that used to send much of their plastic and paper scrap abroad, and is a small but symbolic step toward curbing plastic waste.

A Trade With Few Rules

The Basel Convention, which governs the international waste trade, was adopted in 1989 in response to egregious cases of hazardous waste dumping on communities in Africa, the Caribbean and Asia. Many of its goals remain unfulfilled, including a ban on shipments of hazardous waste from wealthy to less-wealthy nations for final disposal, and a liability protocol that would assign financial responsibility in the event of an incident. And the agreement has largely failed to encompass newer wastes, particularly discarded electronics.

The new provision, proposed by Norway with broad international support, takes a more aggressive approach. It moves plastic scrap from one category – wastes that can be traded unless directly contaminated – to another group of materials that are not deemed hazardous per se, but are subject to the same trade controls as those classified as hazardous. Now these plastics can be shipped overseas for disposal or recycling only with the express consent of the importing country.

The United States signed the treaty in 1989, but never ratified it and is not bound by the treaty’s terms. However, Basel Convention member countries cannot accept any restricted waste imports from the United States unless they have reached a bilateral or regional agreement that meets Basel’s environmental provisions. The U.S. already has such an agreement with fellow OECD member countries.

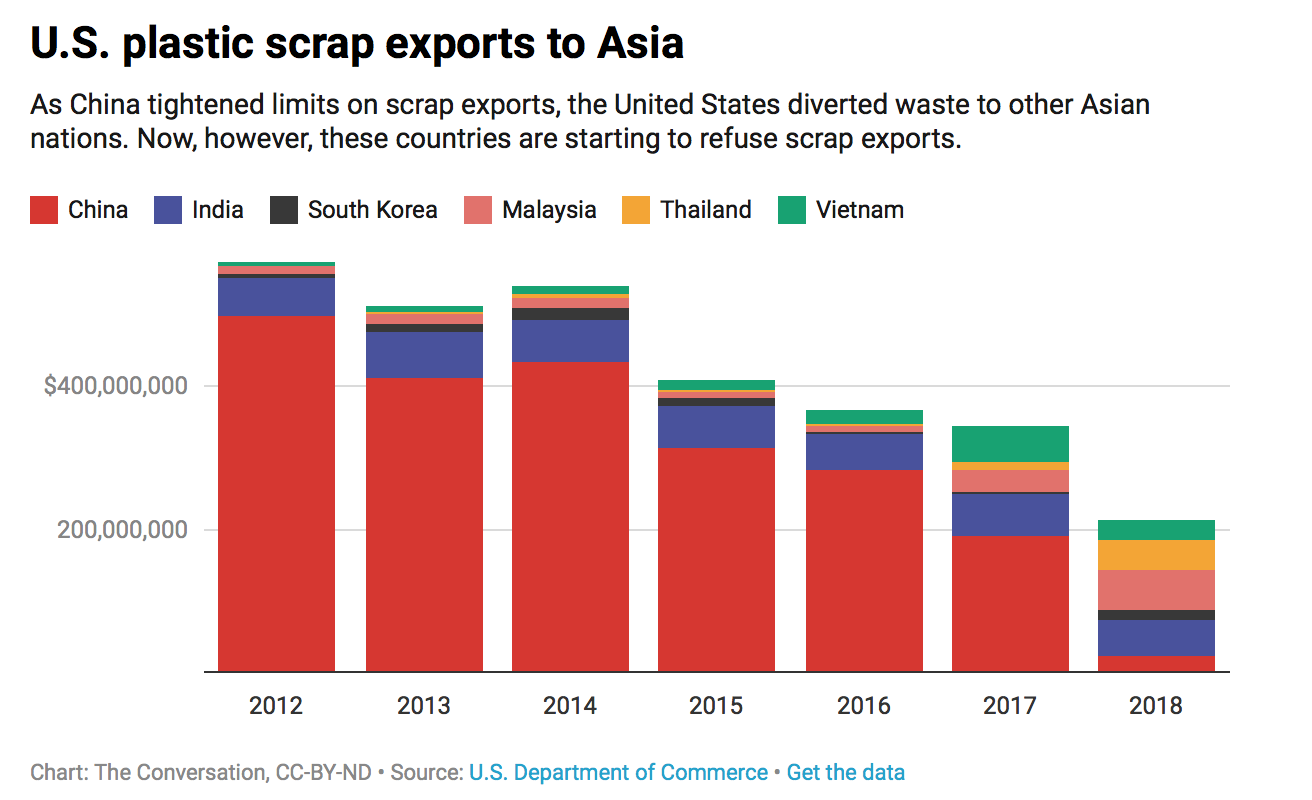

Operation National Sword, China’s policy restricting imports of post-consumer scrap, was a major driver for updating the treaty. Before the ban China imported nearly half of the world’s scrap plastic and paper. Now scrap exporters in wealthy nations are struggling to find alternate markets overseas and boost domestic recycling.

Crisis and Opportunity for US Recyclers

Trends in the United States illustrate these wrenching shifts. Plastic scrap exports to China plummeted from around 250,000 tons in the spring of 2017 to near zero in the spring of 2019. Overall, U.S. exports of plastic waste to all countries fell from 750,000 tons to 375,000 tons over the same period.

Most U.S. waste and recycling policies are made at the local level, and the past year has been a transformative period. Without ready markets abroad for scrap, recyclers are raising prices, which in turn is leading some municipalities to reduce or eliminate curbside recycling programs. Many plastic products in groups 3-7, the least recyclable types, are being sent to landfills.

More positively, recycling authorities have launched public education campaigns, and investment in recycling infrastructure is on the rise. There is palpable energy at trade meetings around improving options for plastics recycling. Chinese companies are investing in U.S. pulp and paper recycling plants, and may extend into plastics.

Here's what you can and can't #recycle in Portland. ♻️ pic.twitter.com/PeZnsPE9MI

— The Oregonian (@Oregonian) May 27, 2019

Green-leaning states and cities across the nation have passed strict controls on single-use consumer plastics. However, businesses are pushing back, and have persuaded some U.S. states to adopt preemptive measures barring plastic bag bans.

The greatest immediate pressure is on international scrap dealers, who are most immediately affected by the Norway Amendment and vocally opposed it. They are also under stress from the U.S.-China tariff wars, which could make it difficult for them to send even clean, commercially valuable scrap to China.

Waste or Scrap?

Under the Norway Amendment, nations can still export plastic scrap if it is clean, uncontaminated and of high quality. The measure effectively distinguishes between waste – which has no value and is potentially harmful – and scrap, or discarded materials that still have value.

This bifurcation matters for the U.S. and other countries that formerly outsourced their recycling to China and are having trouble creating domestic demand for recovered plastics, because it makes a legitimate trade in plastic and other marginal scrap possible. However, there is still no guarantee that this scrap can be reprocessed without harm to workers or the environment once it has reached the importing country.

Nor will the Norway Amendment do much to reduce marine plastic pollution directly. Only a tiny fraction of ocean plastics originate from shipped plastic scrap from rich countries. Most come from items that are used and discarded on land and never enter a recycling system.

Curbing plastic pollution will require broader action, with a focus on coordinating scattered global initiatives and building up relevant international law. Implementing extended producer responsibility for plastics, which could require manufacturers to take plastic products back at their end of life and dispose of them in approved ways, would be a useful step. However, it should not supplant ongoing efforts to reduce production and use of plastics, which contribute to climate change as well as waste.

Solutions may come from the top down in European nations or the bottom up in the United States. But as one Asian country after another shuts the door on scrap exports, it is becoming increasingly clear that business as usual will not solve the plastic pollution challenge.

For what I know the crap that is exported is the part more difficult/expensive to recycle, basically because it is the result of mechanical separation processes that remove easily recyclable materials and leaves a final mixture that would require a lot of handwork to separate as well as almost unrecyclable stuff composed of various materials.

I hope this move really makes rich countries really responsible about their crap.

It would seem that it’s time for us to learn how to take care of our own waste…. these folks have an interesting approach… https://preciousplastic.com/en/videos/build/index.html

It seems that the Summers memo was not a joke as Larry Summers claimed but an actual blueprint-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Summers_memo

It is only when we in the west run out of countries to dump our trash into will we be forced to deal with it ourselves which to a large extent will mean not creating it in the first place. Banning shopping bags and straws is a nice token effort but it is not even a taste of the changes that will be needed to be undertaken.

” Implementing extended producer responsibility for plastics, which could require manufacturers to take plastic products back at their end of life and dispose of them in approved ways, would be a useful step.

However, it should not supplant ongoing efforts to reduce production and use of plastics, which contribute to climate change as well as waste.”

My observations lately is that Plastic Pollution is presented by media as a consumer problem but not as a Plastic Producers problem. The above quote from the article is a reflection of that–imo. Even the link to–Extended Producer Responsibilities–(PDF for Purchase) is slippery.

If I buy Peter Pan Peanut butter in a plastic Jar, I want Conagra to have a system emplace to take the Jar back–or something equivalent. Conagra privatizes the profits from the sale of the Jar and contents. And then Conagra socializes the cost of disposing of their container to every household in our county.

We need to do better, can do better, should do better, than this.

Plastic Producers are not being held responsible. Conagra holds a Corporate License granted by this Societies(USA) Government for its business operations. Failing to Adopt a circular economy for its product packaging should disqualify it from holding a Corporate License and doing business in this country.

And I’ll mash my own peanuts.

just a reminder–the three R’s are: Reduce–Reuse–Recycle

It’s “waste” or “scrap” because there’s no money in it. Junk/scrap yards are not spiffy enough for our sparkling modern world. We need to get over it. Let’s pass a regulation requiring all manufacturing to be reversible. And make recycling a viable industry. There are all those empty malls just waiting to house, sort, pulverize, melt and smelt it all. They can start by ripping out their own lovely interiors, sorting and storing stuff, while they develop processes to recycle everything. And all the raw materials – plastic or metal or textile – get recycled back to their components or elements. Former malls also have very expansive parking lots where bales of recyclables can be stored. All this takes is organization. The money will follow because it is a value on at least two levels – one just cleaning up the environment and two, the value of the materials. To get this off the ground in any meaningful way will require direct spending by the government.

The external social costs related to ecological impacts etc. are not factored into the recycling costs. So the only factor in recycling is whether or not the recycling is cheaper than buying new product.

One of the reasons that landfill costs have gone up in the US for disposal of solid and hazardous waste is that future costs of closing the landfill and long-term O&M have to be reserved for up front so their is a fee per ton of waste disposed to go into that reserve. This has provided an economic reason to consumers to recycle, but not producers.

For many glass bottles and aluminum cans, we pay a nickel for the bottle/can and we get it back when we recycle. so there is an economic incentive. Until society is willing to cause producers and consumers to bear the economic pain of all of this plastic trash getting dumped around the world causing massive ecological and social problems, the easiest option is just to dump it. We see the same thing with agricultural runoff and city sewage systems. It is the downstream recipients that pay the price of the estuary dead zones and algae blooms in the lakes, not the people who made the nutrients or dumped them in the watershed.

so it is all about getting the consequences aligned with the entities generating the source of the consequences. This is simply a massive Tragedy of the Commons problem and usually the only solution is regulation.

Thanks for the video showing what’s recyclable in Portland, and probably here as well. I still need to check on the local list. Some notes:

I compost paper to-go cartons; they break down well. Also paper towels and similar (coffee filters! Coffee grounds are strong fertilizer). “Tubs” are handy household containers, both for food and other items. The main problem is matching the lids, since they have to fit properly to keep, eg, mealworms out. Standardizing those would be big help. I prefer clear containers, since I don’t have to label them, but use white ones in the freezer – you have to label those anyway. And clamshells, not recyclable, are handy for small parts in the shop. Again, because you can see into them.

We also wash and reuse plastic bags, until they spring holes. These days a lot of them have zip closures, so we no longer buy those. Tortilla bags, in particular, though a way to buy those in bulk would help. I don’t try to save the breadbags with big labels glued on them; they’re awkward to use, and the paper comes off on things when you wash them. I take clean bags to the store with me, as well as other containers, for produce. It may matter that we shop mainly at the co-op.

I wrote before about the state inspector shutting down a lot of container re-use at the Co-op; I sent the governor a petition but haven’t heard back – unusual for a politician. This is our “progressive” governor in deep-blue Oregon.

And again: individual efforts would help a lot if everybody did it, but that isn’t going to happen. Only systemic efforts will actually solve the problem. That pretty much means government action.