Yves here. To give you a bit of break rom the loud warble coming from far too many news outlets, here’s a point of entry into a classic debate about fairness, or more specifically, equality versus equity.

In case you missed it, there’s been a war on equity in the form of the law and economics movement. From ECONNED:

The third avenue for promoting and institutionalizing the “free market” ideology was inculcating judges. It was one of the most far-reaching actions the radical right wing could take. Precedents are powerful, and the bench turns over slowly. Success here would make the “free markets” revolution difficult to reverse.

While conservative scholars like Richard Posner and Richard Epstein at the University of Chicago trained some of the initial right-leaning jurists, attorney Henry Manne gave the effort far greater reach. Manne established his “law and economics” courses for judges, which grew into the Law and Economics Center, which in 1980 moved from the University of Miami to Emory in Atlanta and eventually to George Mason University.

Manne had gotten the backing of over 200 conservative sponsors, including some known for extreme right-wing views, such as the Adolph Coors Company, plus many of the large U.S. corporations that were also funding the deregulation.

Manne is often depicted as an entrepreneur in the realm of ideas. He took note of the fact that, at the time, the University of Chicago had one of the few law schools that solicited funding from large corporations. Manne sought to create a new law school, not along conventional brick-and-mortar lines (his efforts here failed), but as a network. He set out to become a wholesaler, teaching law professors and judges. However, although Manne presented his courses as teaching economics from a legal perspective, they had a strong ideological bias:

The center is directed by Henry Manne, a corporate lawyer who has undertaken to demolish what he calls “the myth of corporate responsibility.” “Every time I hear a businessman acknowledge public interest in what they do,” Manne warns, “they invite political control over their activities.” At Manne’s center in Miami, interested judges learn how to write decisions against such outside political control couched in the new norms of market efficiency.

Manne approached his effort not simply as education, but as a political movement. He would not accept law professors into his courses unless at least two came from a single school, so that they could support each other and push for others from the law and economics school of thought to be hired.

The program expanded to include seminars for judges, training in legal issues for economists, and an economics institute for Congressional aides. A 1979 Fortune article on the program noted that the instructors “almost to a man” were from the “free market” school of economics. Through 1980, 137 federal district and circuit court judges had finished the basic program and 56 had taken additional “advanced” one-week courses.

It is hard to overstate the change this campaign produced, namely, a major shift in jurisprudence. As Steven Teles of the University of Maryland noted:

In the beginning, the law and economics (with the partial exception of its application to antitrust) was so far out of the legal academic mainstream as to be reasonably characterized as “off the wall.” . . . Moving law and economics’ status from “off the wall” to “controversial but respectable” required a combination of celebrity and organizational entrepreneurship. . . . Mannes’ programs for federal judges helped erase law and economics’ stigma, since if judges— the symbol of legal professional respectability—took the ideas seriously, they could not be crazy and irresponsible.

Now why was law and economics vantage seen as “off the wall?” Previously, as noted above, economic thinking had been limited to antitrust, which inherently involves economic concepts (various ways to measure the power of large companies in a market). So extending economic concepts further was at least novel, and novel could be tantamount to “off the wall” in some circles. But with hindsight, equally strong words like “radical,” “activist,” and “revolutionary” would apply.

Why? The law and economics promoters sought to colonize legal minds. And, to a large extent they succeeded. For centuries (literally), jurisprudence had been a multifaceted subject aimed at ordering human affairs. The law and economics advocates wanted none of that. The law and economics advocates wanted none of that. They wanted their narrow construct to play as prominent a role as possible.

For instance, a notion that predates the legal practice is equity, that is, fairness. The law in its various forms including legislative, constitutional, private (i.e., contract), judicial, and administrative, is supposed to operate within broad, inherited concepts of equity. Another fundamental premise is the importance of “due process,” meaning adherence to procedures set by the state. By contrast, the “free markets” ideology focuses on efficiency and seeks aggressively to minimize the role of government. The two sets of assumptions are diametrically opposed.

By Peter Dorman, professor of economics at The Evergreen State College. Originally published at Econospeak

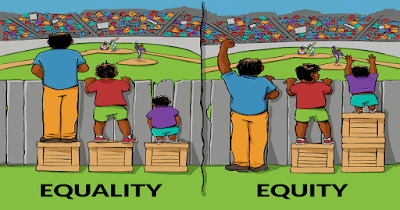

Here’s the graphic, widely used to explain why equity outcomes require unequal treatment of different people.

Benjamin Studebaker (hat tip Naked Capitalism) doesn’t like it at all: “I hate it so much.” But his complaints, about the way the graphic elides classic debates in political theory, strike me as being too redolent of grad school obsessions. The graphic is not trying to advance one academic doctrine over another; it just makes a simple case for compensatory policy. I agree in a general way with this perspective.

Consider the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, which mandates special facilities in public buildings to accommodate people in wheelchairs or facing other mobility challenges. This is unequal treatment: extra money is spent to install ramps that only a few will use, rather than for amenities for everyone. But it’s a great idea! Yes, compensation is concentrated on a minority, but it aims to allow everyone to participate in public activities, and in doing this it embodies a spirit of solidarity that ought to embrace all of us. By making a simple, intuitive case for focused compensation, the graphic captures the spirit behind the ADA and many other policies that take account of inequalities that would otherwise leave some members of the community excluded and oppressed.

Unfortunately, however, there are serious limitations to the graphic; above all, it embodies assumptions that beg most of the questions people ask about compensatory programs. Some are challenges from conservatives of a more individualistic bent, others might be asked by friendly critics on the left, but all are worthy of being taken seriously.

1. Watching the game over the fence is binary: either you can see it or you can’t. In the real world, however, most activites are matters of degree. You can learn more or less of a particular subject in school, have a better or worse chance of getting the job you want, live in a bigger or smaller house or apartment. How much compensation is enough? At what point do we decide that the gains from ex post equity are not large enough to justify the other costs of the program, not only monetary but possible conflicts with other social objectives? Every teacher who has thought about how much extra attention to give those students who come to the classroom with extra needs has faced this problem.

2. Watching the game is passive, an act of pure consumption. Things get more complex when inequalities involve activities that produce goods of value to others. For instance, how would the graphic address compensatory programs for the baseball players? Yes, a player from an underserved, overlooked community should get an extra chance to show they should be on the team. But should the criteria for who makes the team be relaxed? How and how much? In case you haven’t noticed, this gets to the core of debates over affirmative action. Again, I am in favor of the principle of taking extra steps to compensate for pre-existing inequalities, but the graphic offers no guidance in figuring out how far to go in that direction.

3. Height is a largely inherited condition, but what about differences in opportunity that are at least partly the result of the choices we make ourselves? This is red meat to conservatives, who denounce affirmative action and other compensatory policies on the grounds that they undermine the incentive to try hard and do one’s best. I think this position is too extreme, since inherited and environmental conditions are obviously crucial in many contexts, but it would also be a mistake to say that individual choices play no role at all. Again we are facing questions of degree, and the graphic, with it’s clear intimation that inequality is inborn and ineluctable, doesn’t help.

4. The inequality depicted in the graphic is height, which is easily and uncontroversially measured. Most social inequalities are anything but. Student A went to a high school with a library; student B’s high school didn’t have one. That’s a meaningful inequality, and if an opportunity can be awarded to only one of them, like entrance into a selective college program, it ought to be considered. But how big an effect should we attribute to it? Damned if I know.

5. There is no real scarcity facing the three game-watchers in the graphics. There are enough boxes to allow everyone to get a good view and enough fence space for everyone to share. In the real world neither tends to be true. Resources that can be devoted to compensatory programs are limited, especially on a global scale, which, if you’re really an egalitarian, is how you should think about these things. Even locally, the money often runs short. The college I used to teach at could be criticized for not doing enough for students from low income and rural backgrounds with weak K-12 systems (I certainly did), but even with the best of intentions the money was not there. Of course, where the goods to be distributed are competitive, like slots in a school or job openings at a company, the problem is that there’s not enough fence space to go around. Yes, we should take action to provide more opportunities and reduce the competitive scarcity. No, this won’t make the scarcity go away completely.

6. The graphic shows us three individuals and asks us to visually compare their heights. America has a population of over 320 million, and even “small” communities can have a cast of thousands. Surely we are not expected to make individual calculations for every person-by-person comparison. No, those using the graphic usually have in mind group comparisons—differences requiring compensatory interventions according to race, class, gender, ability status, etc. But while that makes things easier by reducing the number of comparisons, it makes everything else much harder to figure out: How do we measure group advantages and disadvantages? How do we account for intersections? Are they additive, multiplicative or something else? Do all members of the group get assigned the same advantage/disadvantage rankings? If not, on what criteria? These are tremendously difficult questions. I am not suggesting that they force us to abandon an egalitarian commitment to substantive, ex post equality—quite the contrary, in fact. We do have to face them if we want to reduce the inequality in this world. My point here is that, by depicting just these three fans watching a baseball game over a fence, one tall, one medium, one short, the graphic is a dishonest guide to navigating actual situations.

My bottom line is that, while I agree with the spirit of the graphic that policies, whether at a single office, a large institution or an entire country, should take account of the inequalities people face in real life and try to compensate for them, how and how far to go is difficult to resolve. Achieving ex post equality is complicated in the face of so many factors that affect our chances in life, and on top of this, equality is only one of many values we ought to respect. The real world politics of affirmative action, targeted (as opposed to universal) benefit programs and the like reside in these complexities. The equity graphic conveys the initial insight, but the assumptions packed into its story make it harder rather than easier to think through the controversies that bedevil equity politics.

This goes back to what I call justice vs fairness.

Justice is supposed to be blind, with the same outcome for all. It ain’t so at the moment, but let’s suppose we’d get a perfect justice.

It still would not be fair. Fine of 1k may mean bankruptcy for some, and way beyond the level of recognition for someone else.

But if you start getting into “fair”, it has its own problems. Namely, fair depends on the context, and the context may vary – what is fair in one context may be deeply unfair in another, and it’s possible that there’s no solution where something is “fair” in all possible (or even majority) contexts.

Justice is blind really means it declaratively sets the context and recognises no other. But if we lock the context for fairness, we’ll generate some unfair outcomes.

That all said, the fact that the perfect outcome is unachievable doesn’t mean we’d not strive for a better one.

> context may vary

Precisely a point. Abstract words require context when applied to concrete cases. The main case for ‘equal’ is likely “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence. The context there especially is a retort to the divine right of royalty.

Abstractions are particularly subject to korinthenkacking, “questions of degree”. Commitment to decisions tend to binarism, and (imo) usually based on one or two factors, with a third for nuance.

For all the dithers, there is an egalatarianism inherent in the image; universally, everyone has been a child and at some point has felt the pain of being too small. That emotional impact is part of its success.

I think this argues for why a human element – judges – are indispensible for taking into account context and setting consequences appropriately. So Yves’ introduction about the co-optation of the judiciary by Law & Economics is pertinent. It is vital for society to require the judiciary to act in the public interest. Manne’s framing of this as “political control” is not completely wrong. The kind of judicial reform we (I) would like to see needs to articulate what “public interest” means. I find Dorman’s grappling with this graphic to be a helpful start. The left seems deficient in thinking about this kind of complexity (though perhaps I’ve missed it).

Wow, hadn’t seen this before. Kinda fun to think about. Maybe the whole point is just to illustrate the difference in the definitions of the two words in an Ikea sorta way. Haven’t seen the Studebaker critique so I don’t know what his issues are.

I also have no idea what the “classic debates in political theory” wrt this graphic are. But a few thoughts occur to me–can the short guy cut a hole in the the fence, or do the “rules” say that the only way to see the game, without buying a ticket of course, is by looking OVER the fence?

Is there a legitimate reason for the fence at all? If so, what is it? If not, why is it there? Why are there no wheel chairs in the picture, when the discussion involves disabled accommodation? Why do the kibitzers in the graphic appear to be minorities, no whites?

Gotta take the dog to the vet now. Will look for the Studebaker piece later. Maybe he answers my questions.

The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.

Anatole France

I have always found this graphic both confusing and troubling. Why are the three central figures watching the game outside the park? Isn’t the difference between the outside the fence watchers and the comfortably seated audience inside the park a question of equality and equity? Are equity standards only applied to people relegated to not only ‘second class seating’ but standing room only areas? Finally, do the people inside the park get to decide not only who gets into the park but also how well or poorly the excluded fence watchers execute a workaround to subvert the exclusionary practices implied by the presence of a fence?

Another angle: all three are cheating, trying to watch the game without paying. If everybody did that…

The point of the pictures is to simplify the concepts enough to provide a working definition – though as Studebaker wrote, it isn’t a very good definition.

In simplifying it so much, it leaves a tremendous amount out and dodges a legion of questions – both our writers seem to agree that it dodges crucial questions.

In the end, it’s just a cartoon. You’re right: the field would have guards out there to prevent this sort of thing, unless they were consciously offering charity.

Why has no one made note of the fact that the people in the graphic are all excluded, presumedly because of lack of the price of a ticket?

And is that lack of money due to the fact that they are all people of color, and so subject to the economic inequality, based on racial prejudice, that plagues our system?

To me, the graphic portrays, in sub-text, the notion that people with less can/should be happy with less than full participation in the culture in which they live, so long as that austerity is ‘properly’ distributed amongst those ‘outside‘ the fence.

Neo-liberal economics has resulted in more and more Americans finding themselves on the ‘outside’, looking in, and a great many of them are quite upset about that because they remember a better time, and understand that in a very real sense, they’re situation is the result of the callous, and willful behavior of elites who’ve profited in ruining their quality of life.

To take my analysis a bit further, IMO, it is the ‘nouveau poor‘ who, because of their belief that they deserve the better life they clearly remember, and so recently lost, insist that the ‘equality‘ portrayed in the left panel is reasonable, and should be accepted because it is obviously evenly distributed.

This misinformed opinion might be attributed to their lack of experience with their new life ‘outside‘, where people over time learn to cooperate in making do with less.

There is a rich literature dealing with this reality, think The Prince and the Pauper, or even the teachings of Jesus, and the Buddha.

The folks who believe in MAGA, are refusing to adjust, and believe that somehow, they will regain their rightful place in an economy that has clearly decided to leave them behind, and ‘outside‘.

Our job then, is to help them understand that their only real hope for a better life is in solidarity with the rest of us, in our fight to get everyone a place inside the fence.

This job is obviously a long, up hill battle, largely because of the long history of the PTB stigmatizing socialism, dividing to conquer, and of course the MSM’s total abandonment of their civic duty.

It’s Bernie or bust!

And, that the little kid will, unless they are a midget, grow to the point where they can see over the fence?

Oh, and poor white people, who outnumber blacks? What about them?

Socialism flattens the fence so anyone who wants to watch can take a seat in the stadium.

Exactly!

Cuba is a baseball-crazy country, how many people in Cuba are watching from over the fence?

I odce spent a few months in Cuba. It is absolutely not a model for most things. One anecdote: an employee of the film industry (ICAIC) told me she gave some desperately poor friends movie theater tickets. They ended up not going because they couldn’t afford the bus fare. A bigger issue: the daily struggle to get enough to eat beyond rice, beans, and sugar. We can debate the role of the US in turning Cuba into a near prison, and all sanctions need to stop now, but it is what it is.

We can debate the role of the US in turning Cuba into a near prison, and all sanctions need to stop now, but it is what it is.

And we can debate why, without sanctions, the US has the largest prison population in the world at the highest rate of imprisonment. Tthough, of course, there is “no daily struggle” for food…or healthcare…)

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2019.html

Cuba is an actual country with 11 million real people in it, not just a set of talking points or a hypothetical. Of all the manifestations of North American arrogance, being made into fairy tales pisses off Latin Americans, including the left, about as much as any. We can abolish the current prison model and also abolish the sanctions on Cuba and do other things not to make their already difficult lives worse.

A country a hundred miles from Disney World has the boot of the US state pressing down on its suffering people and most American leftists only talk about it in terms of an internal US political debate. Exhibit 10000 of why the American left sucks.

And yes, Cuba today distributes what resources it does have so unequally that it is not a great model of social justice.

In the graphic, there are at least three games going on: the baseball game, about which we don’t learn very much; the game of the fence, which is solved with box arrangements, or by taking it down; and the game of the definitions of ‘equality’ and ‘equity’, which comes through the fourth wall into the world in which the cartoonist is trying to prove something. According to my communistic prejudices, I would have said the only just solution would be to remove the wall, but it could be that the baseball game is dependent on the wall — I would think most goods produced by labor, especially performances, would require some defining structure — and certainly the word game requires the wall as part of its raw material.

Or, replace the wall with clear plexiglass, thus retaining the nature of the game but removing the market barriers that keep people without access to funds from enjoying the game.

Indeed. “The baseball game is dependent on the wall.” Because, for one, who wants to run all the way to the river and wade in after the stupid ball? Baseball is an enjoyable distraction. So, to carry this metaphor, is the economy. Equity, to me, was always an equal share of something. A stake in something. Equal justice under the law. Without equity, as is now dawning on me, there can be no hope of equality. Little Manu Macron, in a burst of hypocrisy, told Trump that the difference between France and the US was that France was based more on social justice. Justice. I really don’t see that as fundamentally French. But I definitely don’t see it as fundamentally USA. “Equity” is as much verbiage as “Equality”. We might want to start looking at the antonyms. Neoliberalism is “accumulation by dispossession” (David Harvey)… so there’s no equity there. Hence no equality.

A version of this graphic was used at a civic engagement seminar on multi-modal transportation accessibility I attended last night. It featured one twist – the replacement of the slotted fence with a chain link fence so that all could see the game “because the cause of the inequity was addressed. The systemic barrier was removed.” In the context of the presentation about accessibility in the city, the presenter mentioned universal design. This reminded me of Bucky Fuller’s anticipatory design since both seek to think comprehensively (i.e. inclusively) about design challenges and to accommodate the maximum number of beneficiaries while doing harm to the least number possible. Seem equitable to me! The designer of the equity meme has a great post at Medium that provides a thorough overview of how the graphic has evolved (including the the chain link fence addition), the variety of interpretations, and how the “famous” meme has spread far and wide.

Is Mr. Dorman damning this image with faint praise? I think it’s a brilliant way of illustrating how an issue can be turned on it’s head and looked at from a different perspective.

It presents the difference between equality of opportunity vs. equality of outcome. Even some self-labeled progressives (perhaps in order to appease conservatives?) have claimed they are only interested in the former, not the latter. The graphic shows how meaningless that way of judging results is.

The first step in trying to achieve good outcomes for all is to listen to all. This gets my goat:

Well, that’s what individuals do, and if you respect them you take their perceptions of inequity as data for your distributed computation. Not everyone wants the same thing. Some people don’t even like baseball.

And yes, that fence around the field is a good starter for a conversation about the problems of enclosure. You wouldn’t need the damn boxes if you hadn’t blocked the view.

Wow, hadn’t seen this before. Kinda fun to think about. Maybe the whole point is just to illustrate the difference in the definitions of the two words in an Ikea sorta way. Haven’t seen the Studebaker critique so I don’t know what his issues are.

I also have no idea what the “classic debates in political theory” wrt this graphic are. But a few thoughts occur to me–can the short guy cut a hole in the the fence, or do the “rules” say that the only way to see the game, without buying a ticket of course, is by looking OVER the fence?

Is there a legitimate reason for the fence at all? If so, what is it? If not, why is it there? Why are there no wheel chairs in the picture, when the discussion involves disabled accommodation? Why do the people in the graphic appear to be minorities, no whites?

Gotta take the dog to the vet now. Will look for the Studebaker piece later. Maybe he answers my questions.

I think a big challenge in the US is the general assumption that equality, equity, etc. are a zero-sum game. If somebody gets something, then other people have lost. I think this thinking is one of the reasons that we have seen low productivity growth over the past couple of decades.

If the lower-class elements in society can get better conditions and opportunities, they also have the opportunity to contribute more to society which increases the total size of the pool for everybody to split. High inequality, such as now, means that many people are not able to contribute to their full potential, which means the total size of the pool can be smaller than it otherwise might be.

I don’t think it is accidental that one of the great economic booms of all time occurred from about 1950 to 2000 when the US:

1. Helped fund reconstruction of Europe and Japan after WW II;

2. Instituted the GI Bill which allowed many people who would never have gone to higher education to do so;

3. Desegregated schools and generally allowed minorities to participate more fully;

4. Encouraged women to participate more fully in society; and

5. Disabled people could participate more fully.

All of these factors contributed to substantial growth in the 50s-90s period as more and more groups become economically prosperous. However, we are now going to the ultimate meritocracy where the economic winners are beginning to crush the people who have not done as well and concentrate wealth at the top. As a result, the growth has stagnated as mobility is decreasing and the upper pools are not growing.

1950-2000? I think the key date is 1973, when labor productivity was detached from wage compensation. That’s your neoliberalism kicking in, and it kicks on (and down).

Destroying the equity powers of the federal courts was a major goal of Rehnquist & Co. For the most part, mission accomplished.

I think that Benjamin Studebaker’s critique is right on target, and I also think that his “What’s Left” podcast is the best of its kind.

On the other hand, I wouldn’t trust anything that comes out of Evergreen State University in the wake of its “diversity” witch hunts from a couple of years ago.