In September, ProPublica selectively vetted and publicized the findings of an international study by the German company Greenbone Networks which found widespread and serious deficiencies in the protection of patient medical images, like MRIs, CAT scans, and mammograms and related patient data (identifiers like name, data of birth, Social Security number) all over the world. Very few countries got a clean bill of health, and the US found to be particularly lax.

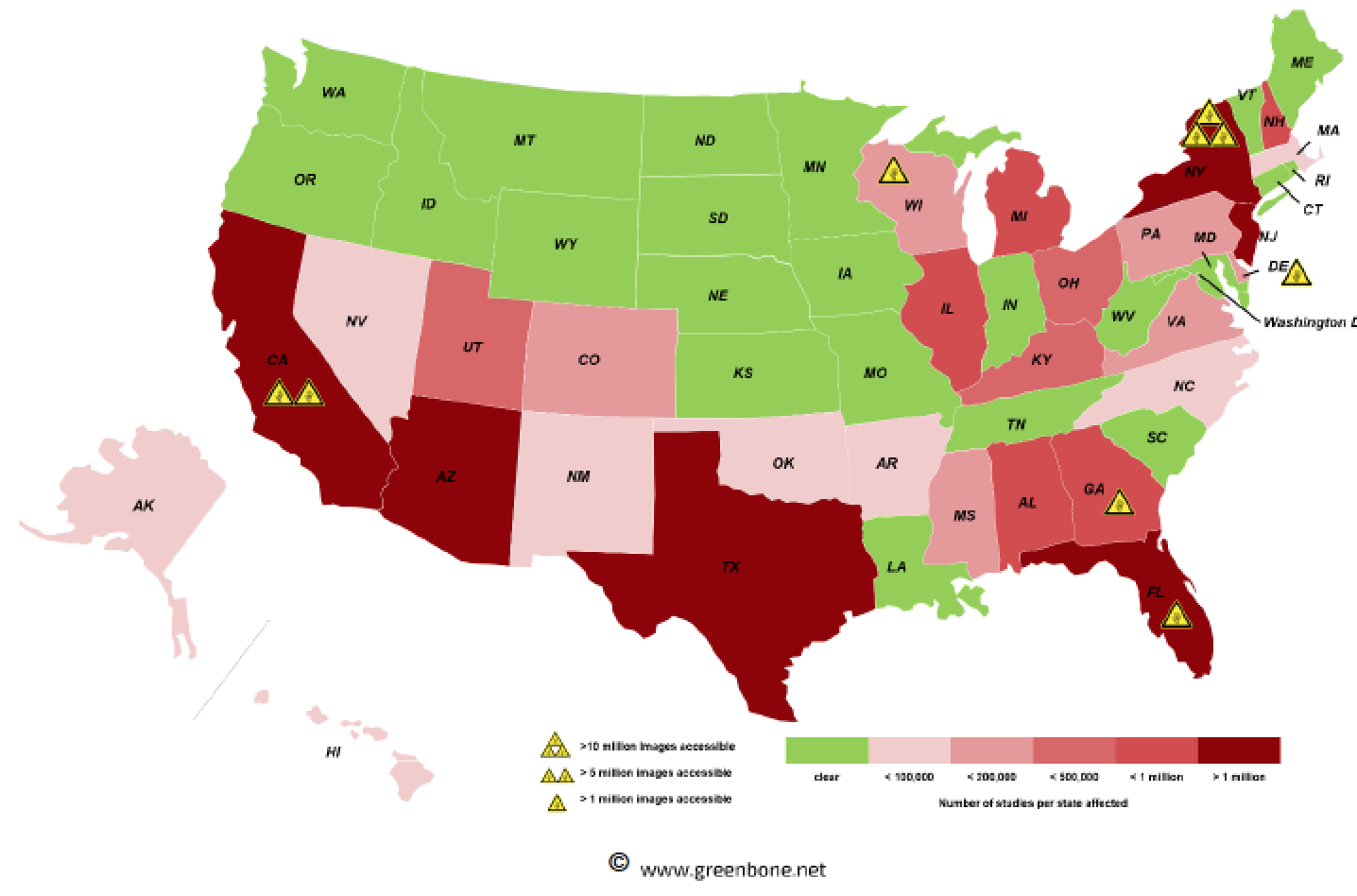

Greenbone made a second review. As a result of the report, 11 countries, including Germany, the UK, Thailand, and Venezuela, took all Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS) servers offline. However, in the US, which Greenbone had classified as “ugly” in its “good, bad, and ugly” typology, got even worse. In the US, Greenbone identified 786 million exposed medical images, which is a 60% increase from when their original survey was completed, to September. Not only does the data have patient identifiers, but it can also include the reason for the test, ID cards and for members of the armed forces, military personnel IDs. This growth occurred despite some of the companies called out in the ProPublica report taking corrective action. From the latest report, which we have embedded at the end of the post:

For the most part, this data isn’t merely hackable, it’s unprotected.

This situation is bad for patients. First is the exposure to identity theft, both for financial fraud (getting credit in your name) and medical fraud (getting medical services in your name and leaving you and your insurer with the bill). Second is the possibility of vindictive use of sensitive health information. From the ProPublica story:

“Medical records are one of the most important areas for privacy because they’re so sensitive. Medical knowledge can be used against you in malicious ways: to shame people, to blackmail people,” said Cooper Quintin, a security researcher and senior staff technologist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital-rights group.

“This is so utterly irresponsible,” he said.

And at least one US official is up in arms. From an early November press release by Senator Mark Warner:

U.S. Sen. Mark R. Warner (D-VA), Vice Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee and co-founder of the Senate Cybersecurity Caucus, today raised concern with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)’s failure to act, following a mass exposure of sensitive medical images and information by health organizations. In a letter to the HHS Director of the Office for Civil Rights, Sen. Warner identified this exposure as damaging to individual and national security, as this kind of information can be used to target individuals and to spread malware across organizations.

“I am alarmed that this is happening and that your organization, with its responsibility to protect the sensitive personal medical information of the American people, has done nothing about it,” wrote Sen. Warner. “As your agency aggressively pushes to permit a wider range of parties (including those not covered by HIPAA) to have access to the sensitive health information of American patients without traditional privacy protections attaching to that information, HHS’s inattention to this particular incident becomes even more troubling.”

“These reports indicate egregious privacy violations and represent a serious national security issue — the files may be altered, extracted, or used to spread malware across an organization,” he continued. “In their current unencrypted state, CT, MRI and other diagnostic scans on the internet could be downloaded, injected with malicious code, and re-uploaded into the medical organization’s system and, if capable of propagating, potentially spread laterally across the organization. Earlier this year, researchers demonstrated that a design flaw in the DICOM protocol could easily allow an adversary to insert malicious code into an image file like a CT scan, without being detected.”

Warner also complained that HHS was giving its Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval to health care providers despite glaring security holes:

In his letter to Director Roger Severino, Sen. Warner also raised alarm with the fact that TridentUSA Health Services successfully completed an HHS Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Security Rule compliance audit in March 2019, while patient images were actively accessible online.

I have always assumed that medical providers are on par with candy stores at data security and this report confirms my prejudices. The ProPublica story described why medical images are so commonly out in the open:

Oleg Pianykh, the director of medical analytics at Massachusetts General Hospital’s radiology department, said medical imaging software has traditionally been written with the assumption that patients’ data would be secured by the customer’s computer security systems.

But as those networks at hospitals and medical centers became more complex and connected to the internet, the responsibility for security shifted to network administrators who assumed safeguards were in place. “Suddenly, medical security has become a do-it-yourself project,” Pianykh wrote in a 2016 research paper he published in a medical journal…

The passage of HIPAA required patient information to be protected from unauthorized access. Three years later, the medical imaging industry published its first security standards.

Our reporting indicated that large hospital chains and academic medical centers did put security protections in place. Most of the cases of unprotected data we found involved independent radiologists, medical imaging centers or archiving services..

Meeting minutes from 2017 show that a working group on security learned of Pianykh’s findings and suggested meeting with him to discuss them further. That “action item” was listed for several months, but Pianykh said he never was contacted. The medical imaging alliance told ProPublica last week that the group did not meet with Pianykh because the concerns that they had were sufficiently addressed in his article. They said the committee concluded its security standards were not flawed.

Pianykh said that misses the point. It’s not a lack of standards; it’s that medical device makers don’t follow them. “Medical-data security has never been soundly built into the clinical data or devices, and is still largely theoretical and does not exist in practice,” Pianykh wrote in 2016.

From a HelpNet Security summary of the second report by Greenbone:

Dirk Schrader, cyber resilience architect at Greenbone Networks said: “Whilst some countries have taken swift action to address the situation and have removed all accessible data from the internet, the problem of unprotected PACS systems across the globe only seems to be getting worse. In the US especially, sensitive patient information appears to be free-flowing and is a data privacy disaster waiting to happen.

“When we carried out this second review, we didn’t expect to see more data than before and certainly not to have continued access to the ones we had already identified. There certainly is some hope in the fact that a number of countries have managed to get their systems off the internet so quickly, but there is much more work to be done.”

My tiny sample may not be representative, but my experience was also that the software imaging centers collect unnecessary but sensitive personal data.

Many years ago, my orthopedist wanted me to get an MRI. He was fussy and had a particular imaging center he liked (he did not have a financial interest in them). When I went to schedule an appointment, the staffer asked for my Social Security number. I refused to give it; I won’t give my SSN to any medical provider because there’s no good reason for them to have it and I assume their security is dreadful. The staffer said she couldn’t book me unless I gave it. I said I was a cash customer, I’d give them a credit card number and they could pre-authorize payment, and in any event, my insurer didn’t use SSNs as an identifier. No dice and so I did not get the MRI, since my MD was also stubborn and would not refer me to another radiologist practice.

That brick wall suggested to me that the SSN was set up as a “must fill” field in their software. I’ve never had that issue with any doctor or other medical test service (note I have not tried to get an MRI since then).

Both the ProPublica story and the Greenbone report strongly urged patients to press their medical providers about their data security:

If you have had a medical imaging scan (e.g., X-ray, CT scan, MRI, ultrasound, etc.) ask the health care provider that did the scan — or your doctor — if access to your images requires a login and password. Ask your doctor if their office or the medical imaging provider to which they refer patients conducts a regular security assessment as required by HIPAA.

And from Greenbone:

For patients it is usually difficult to verify the measures taken by the chain of medical service providers they face. What they can do is to be clear about their expectations about data protection and privacy.

• Ask your doctor about their data protection regime, what they do precisely.

• In case you get the generic answer (We do what is required by law), demand further details like

how often do they verify their IT security and data privacy posture.

• You might not get good or immediate responses, but the same question asked by many again and again will lead to an improvement.

I would also ask about their data retention policies. If you are a one-off patient and the image is not likely to have lasting value (like the chest X-ray I got as part of the Australian visa process, or to rule out a stress or hairline fracture as a cause of pain), I would press to have it deleted in a month or six months, and find out what it would take to have that happen. Even if you don’t get anywhere, it sends a message that patients are concerned about data security.

00 Greenbone medical images update

Not surprising given the HC system and without legislative effort it will worsen. I would bet that the examples found in ‘bad’ countries like France, Italy or Spain are all related with private HC outlets. I like the Morricone take of the study. Funny!

Not bad to ask about privacy, but your doc is probably the wrong person to ask, unless you go to an independent practice. Otherwise, you are giving the doc one more crappy admin thing to think about.

Look up the health group CEO and start sending emails everyday. That person has better capacity and it is part of their job. Most docs have nothing to do with private anymore.

Very good point. I have one of the increasingly rare solo practitioners, so I forgot that most people have doctors who are in practices, often corporatized ones.

But at places like imaging centers/practices, if they aren’t part of a chain (in cities with a lot of teaching hospitals like NYC, you have a lot of independent ones), you can get to an office manager type pretty readily.

I disagree. Anytime I have brought up an issue I am met with hostility and the lie that everything is safe and secure. They are responsible in the sense that the create resistance and force the lie. They might not have direct control but they are the ones who are responsible for using and defending the system.

On a person level whenever I talk to people I know about the problems with data security they get defensive and tell me the tools are good and really I just dont understand how the system works.

My experience as well.

First, if they only get one inquiry a year, it’s easier for them to treat you as unreasonable than if they hear this once every two weeks.

Second, there are more and more stories about data breaches in medicine.

Third, you can print out the ProPublica story and say, “This problem is widespread. You are the type of organization that they said is likely to be remiss. You need to tell me why not” (or a more polite version of that). The article shows that the tools are not good, the tools are not secure by design and where is the security?

I am admittedly more argumentative by temperament. And the objective is not to win, the objective is to get them rattled, particularly if you close by saying that what they’ve said isn’t convincing and they should consider looking into this since if anything bad happens, they could be liable.

“Most of the cases of unprotected data we found involved independent radiologists, medical imaging centers or archiving services.” Unfortunately this vindicates get-big-or-get-out public policies. Yet another poisonous fruit of digitization.

Regarding the US, If you have cancer and don’t live in Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, or New Mexico, I don’t think there’s an option to delete your health data. Detailed health information is submitted to the State/Territory, and then to the CDC by State Law. I’ve no doubt that Google has already accessed it, and Amazon is at a minimum working on it, along with Facebook.

The website says the data is anonymized but it does not indicate where/when that happens.

Indeed, it doesn’t. Also, I’m curious as to why those four States opted out of the CDC Cancer Registry, particularly Connecticut, given some of the historic wealth there. When I was diagnosed with cancer a short while ago (not lung cancer, if anyone’s wondering) I had read a doctor’s quote (I think from MAYO), in a cancer book, that the entire US population was subjected to the registry. Given what I already knew about the Silicon Valley/MIT/CMU, et al, DOD Subsidized Technocracy, it horrified me (as in: you’ll never be able to get a job in your profession again, particularly as a female). I didn’t know some States opted out until I looked up that CDC link this morning.

Having made multiple complaints to HHS Office of Civil Rights regarding HIPAA, I can proclaim that the enforcement arm is useless.

In my one HIPAA challenge I “won,” the Portland, Oregon company ZoomCare was using skype for telehealth. They were chided because they had not entered into a Business Associate Agreement (BAA) with Microsoft, but ultimately suffered no consequences because they stopped using it. HHS said ZoomCare did so “due to low patient utilization and provider concerns regarding impacts on clinical work flow.” Hmm… I wonder about that. A BAA surely comes with costs that most covered entities would want to avoid. And frankly, I don’t think “covered entities” like doctors or small clinics would ever fully understand when one is necessary.

Health app developers send in questions to an OCR platform called ideascale. This question was asked two weeks ago: Doe’s remote access Healthcare provider requires HIPPA complianc

As you can see, some app developers don’t know how to spell, let alone comprehend HIPAA compliance.

It seems to me that HHS OCR’s main role seems is to collect fines when there is a breach.

That’s one way to fund an agency!

But I didn’t win a complaint that use of Kaiser Permanente’s Health Connect in Oregon violated my rights. You see, in order to access one’s electronic health records, one must keep trackers on.

I first complained to Kaiser Foundation Health Plan. The Digital Experience Center responded:

“Please advise the member that our website does use Google advertising service cookies and WebTrends cookies.

The Google advertising service cookies are used so that we do not display advertisements to purchase Kaiser Permanente coverage on Google’s search pages to those who are already members (as this saves money). Information we send to Google is anonymous and aggregated.”

Really???