Yves here. Nathan is correct that making up for income lost to the pandemic would not be inflationary, no matter how big and scary the numbers look. However, as readers no doubt keenly appreciate, the US seems to lack the ability to get there, even if it had the political will. The delays, shortfalls and gaps are already leading to business failures, which destroy jobs, wealth, and leads those who are comparatively well situated to save to make up for anticipated collateral damage, which creates another leg down to the deflationary shock.

And too many officials are fixated with bailout math and mechanisms, and not the vastly more important, “How to alleviate bottlenecks and shortages” problem.

By Nathan Tankus. Originally published at Notes on the Crises

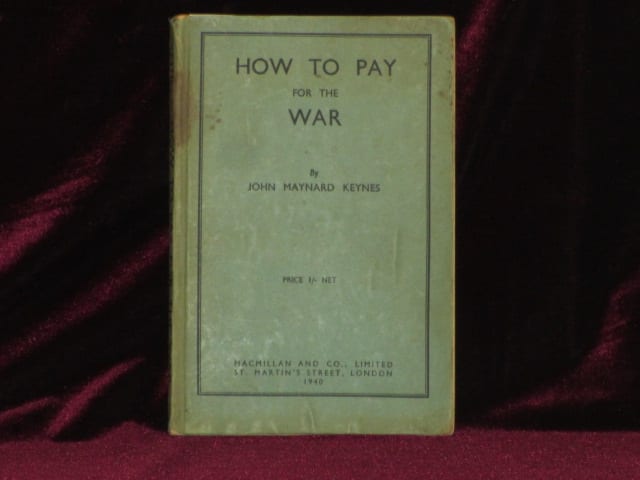

During the 2020 Democratic primary the main theme was “how are you going to pay for it?”. It has been a painful irony that that question evaporated in the smoke of multi-trillion dollar spending programs to fight the Coronavirus depression. Yet, the question isn’t inherently absurd. “How to Pay For the War” was a pamphlet written in 1940 by John Maynard Keynes which is a classic for seriously thinking through the economic effects of a large spending and resource reallocation program. The problem with the mainstream media framing of the question is it was never about the practical economic problem of provisioning a spending program with physical resources without disrupting the functioning of the rest of the economy.

Instead, it was about the easiest thing for the Federal Government to find- money. People were scared of big spending numbers created by counting up spending over a decade-long period. Oftentimes this estimate was improperly compared to 1 year of GDP. This relentless hammering of his spending programs with the “payfor” question has now vanished in the smoke generated by federal reserve officials talking about how they have “infinite” money and congress spending money without payfors without a second thought.

Yet, Bernie’s program did posit a very strong full employment economy and did need to be resourced in physical terms . Many researchers have been working on filling in that void. I myself have been working on a long delayed report entitled “Monetary Policy for a Green New Deal” which introduced the term “non-fiscal payfors” to highlight all the tools from liquidity regulations on non-financial businesses to direct credit regulation that could be used to disemploy resources that could be redeployed. While the analytical tools involved are more sophisticated than Keynes’ time 80 years ago, the problem of resourcing large spending programs under conditions of high employment is basically the same. As Keynes sys:

In making money go further [with cost of living subsidies] it aggravates the problem of reaching equilibrium between the spending power in people’s pockets and what can be released for their consumption.

Many useful frameworks have been developed in the past 18 months since the Green New Deal became a lightning rod in U.S. politics but this issue, how to resource programs under high employment circumstances, has been made largely irrelevant. An unprecedented amount of resources and manpower is idle and unemployed right now. Our problem is not one of permanent shortages because of ongoing flows of nominal income that are “too large”. Our problem is we can’t safely mobilize sufficient resources to conduct emergency services. We are experiencing temporary bottlenecks from either panic buying or the difficulty of reallocating resources to different supply chains. This is not a conventional “run on the supermarket” circumstance.

First – there isn't a food shortage – there's a distribution problem. Usually, ~1/2 of food is purchased at grocery/retail stores, and ~1/2 is purchased away from home at restaurants, schools, hotels, etc. But now, almost all food consumption has shifted to the first category.

— National Farmers Union (@NFUDC) April 6, 2020

Rather than ramping up production as much as we can logistically manage to do in a short amount of time, fighting the pandemic war at the resource level is about the physical redistribution of resources from certain areas to other areas. This means far more people devoted to supply chain management- a job that can at the very least be partially done from home. The trickier part is safely mobilizing people to produce more safety equipment and then mobilizing non-front line workers with spare safety equipment to meet other needs. The production of N-95 masks by means of N-95 masks, as it were.

The second element, which I’ve discussed from the beginning of this blog almost 3 weeks ago, is a financial one. On March 19th I said “The main economic problem is a financial one of balance sheets”. I stand by that. During war time the one concern we don’t really have is people paying their nominal debts. Nominal income suffuses the economy and even businesses in obscure sectors are often paid lots of money to convert their production lines to war-time activities. Today our major economic concern is people’s capacity to pay their bills. We could make up the income of everyone who has lost money out of public funds and this likely wouldn’t lead to excess demand later on, once the pandemic ends. All making up lost income does is allow people to pay their bills and leave them with the same wealth levels they would have had absent a pandemic. It’s hard to see where the problems emerge from this strategy, even as it carries a big sticker price.

Maddeningly, the easiest problem to solve- this financial one- is likely the one that congress will have the most trouble with. The question of resourcing the pandemic one is a matter of supply chain and factory reconversion experts, not economics per-se. What careful economic analysis can tell us is that while we’re on a war-time footing, we’re not dealing with war time resource allocation problems. Any resource that can be safely mobilized, can and should be mobilized and responding to our protective equipment bottleneck will allow us to access a lot of idle resources that are easily available. In other words, in normal times we need fiscal and non-fiscal payfors. Today the payfor question in whatever form is irrelevant as it could possibly be.

P.S. I apparently wrote about the same thing Joe did today.

WE DON'T NEED WAR BONDS TO FINANCE THE WAR

In today's @Markets newsletter, I wrote about why war bonds are not only unnecessary for the fight against COVID-19, but would actually be harmful.

Sign up here to get it in your inboxes https://t.co/e5TYtjIuOw pic.twitter.com/2MOoSLQwsh

— Joe Weisenthal (@TheStalwart) April 7, 2020

TBH, right now the main thing is speed. We all know there will be fraud, and waste. But it all pales against the damage time can do.

Really, if you’d put the cash into trucks, drive them around each household and shovel an evelope with say $3k (or whatever is the average take-home monthly pay for a US household) into each postal box, it’d be much better than ruminating on how to do it most “proper” way.

Exactly. This is the huge problem with the Eurozone in particular – its just not constructed for the sort of radical yet simply policy that is needed. This is precisely the time when you need a real leader to say ‘just send cash to every single account, to hell with administrative fairness’. Yes, there will be fraud and leakage, but it will pale beside the damage of not doing it quickly enough. The only hope for those of us within the Eurozone is that the ECB will turn a blind eye to national governments issuing bonds outside agreed limits (which is already happening of course to some degree) and just doing financial mail drops.

One advantage the EU has there is that the unbanked world is way smaller than the US (about 37-40m out of 500m – these numbers include the UK vs about 55m out of 340m in the US).

So “just credit the accounts” would work much better in the EU than the US, but as you say, the coordination bit would be much harder.

Another advantage I would say in most of Europe (many not Italy, they seem to be struggling), is that existing social welfare systems are more data rich and are better integrated to tax systems. For example, in Ireland it’s been comparatively simple to cut out a few rules and ensure that newly unemployed get additional local government rent support grants (which in turn helps landlords meet their mortgage payments) – normally it takes several months for those payments to go through.

Yup. The main disadvantage in the EUR zone is structural agreement – see how they are unable to agree on the EU bailout parameters.

If the EUR won’t go (in a controlled manner), the EU could very well fall apart by what was supposed to hold it together. But Delors and co were proven wrong – in crisis the EU states won’t share more sovreignty, they will go to their old ways instead.

TBH, you can’t do it easily. Not necessarily because of the actual EU citizens IMO, who, if the EU was really an Europe of regions might like it better than they current central govts, but the central govts don’t want to be made redundant.

Ultimately, all the work needs to be at whatever the key administrative level of society is – in some countries central government, in others regional government, etc. The success of the German model (so far) seems to have been that the Lander have been more responsive and flexible than any national government.

I would say that even in an ideal world, the EU is not the appropriate level to manage a detailed response. What the EU needs to do is open up the floodgates for cash and let national and regional governments do what they are good at – spending it.

How about this?

The Canadian CERB Programme (can’t remember what the acronym stands for) began Monday with People whose birthdays are in Jan. to Mar. It is rolling out over the four days before “Good Friday” this week. The first two days saw about 1.8 million registered. Some of those from the first day, with direct deposit, already have the money in their accounts. Those without direct deposit are supposed to have cheques on the way within three days.

Those who previously registered for Employment Insurance are waiting longer. That expanded programme started before this one. More red tape in EI claims.

I think they need to be careful not give too much money to people who aren’t supposed to have that money. The whole underpinning of the machine so to speak is based on the rat race, you know the idea that the meaning of life is to chase after these dollars, to earn money by working at your job. If they start just giving too much money away or doing it carelessly then they risk upending some of the fundamental assumptions that keep our Capitalist system running: that dollars are a sacred goal of life itself, ordained by that God we Trust in, and that money does not grow on trees but only comes through working hard for your ‘living’.

Yes, the old “deserving versus undeserving poor”. Which misses that the undeserving poor still consume and pay rent…..

They also spend a high percentage of what they get. Which means that if you give them a dollar, that dollar will probably recirculate into the economy in less than 30 days supporting landlords, grocery stores, gas stations etc. it is probably the fastest money velocity in the system.

I have long felt that Social Security is a very important economic fly wheel as the money goes to people who will generally spend almost every penny of it by the end of the month in boom or recession. This is probably the second fastest money velocity in the system.

On the other hand, a tax cut for the 10% (or 1% or 0.1%) is likely to largely get saved (euphemistically known as “investing to create jobs”) and not re-circulated into the economy (although it may be given to another 0.1% percent to buy a Renoir). The corporate tax cuts largely got plowed back into stock buybacks that increased the value of the stocks that…..did not get sold and spent on goods and services. These tax cuts are probably the slowest money velocity in the entire system.

The problem with Eurozone is that it is constructed for the opposite purpose, as it is explicitly banned direct financing of the member states , so the blind eye on the secondary market is always both not unconditionated ( until now ) and precarious and revocable in itself.

Most relief packages linked to the corona virus will experience “last mile” distribution problems so to speak, but I agree that the money needs to go out to the people that need it as a matter of urgency. Any delay relating to matters about administrative fairness is tantamount to “talking while Rome burns”.

That they are proposing corona bonds looks like they are trying to manage their concept of “sovereign debt” as a firewall to protect the euro. When what they need is just a universal distribution mechanism to get the necessary credit to all the members.

Government debt is just a policy decision.

Today’s globalised world is very different from the past.

In the past, very different things occurred in Japan that no one noticed as Japan was so far away.

Japan didn’t need the Marshal Plan to reboot after WW2 even though it was in the same state as European nations.

The BoJ cleared all the bad war debt from the banks, and made them whole again with money they created out of nothing. The banks were then ready to lend into the economy again as if nothing had happened.

The BoJ could create money for the Government to spend into the economy to aid recovery and Japan was soon back on its feet again.

Japan didn’t start issuing bonds until 1965 as the BoJ just created the money for the Government to spend. Not paying interest also helped Japan’s recovery.

There were no financial problems as both Government and private money creation from banks were carefully controlled.

The money supply should correspond to the amount of goods and services being produced in the economy.

Too much money and you get a Zimbabwe (inflation / hyperinflation).

Too little and you get a Greece (deflation / debt deflation)

The Japanese controlled private money creation with credit / window guidance to direct bank lending into business and industry and away from real estate and financial speculation.

The extra money required was given to the Government to spend into the economy.

It all worked really well in Japan until they discovered financial liberalization.

This was the basis for all the Asian Tiger economies, before they discovered financial liberalization and had financial crises a few years later (the Asian Crisis)

Japan made a policy decision in 1965 to start running up Government debt.

Look at them now.

Richard Werner was in Japan when it all went wrong in the late 1980s/1990s.

He could compare the good “before”, to the bad “after” to see what went wrong.

He also looked back, to see how Japan developed its very different economic model that worked so well.

During globalisation we have copied the bad “after”.

How can nations achieve Japanification?

Japan led the way in bad financial practices that could cripple an economy for decades.

In the 1980s it looked as if Japan would take over the world, but bad financial practices have seen their economy flat-lining ever since.

Japanese companies found they could make more money from their financial arms (Zai Tech) than they could from their traditional businesses, for a while anyway.

House prices always go up and their real estate boom would never end, until it did.

Jusen were nonbank institutions formed in the 1970s by consortia of banks to make household mortgages since banks had mortgage limitations. The shadow banks were just an intermediary put in place to get around regulations.

Japan led the way in bad financial practices that could cripple an economy for decades.

Look familiar?

What does it look like?

At 25.30 mins you can see the super imposed private debt-to-GDP ratios.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

What Japan does in the 1980s; the US, the UK and Euro-zone do leading up to 2008 and China has done more recently.

There is the MMT argument and the positive money argument (as above).

Really there is a debt, but it has no effect.

MMT is more precise, the positive money people just look at it in practice.

Sound of the Suburbs, thanks for this post. It has cleared up a lot of confusion I’ve had about the post WWII rebuild in East and Southeast Asia. I once asked a docent on a tour at a history museum in Singapore about where they found the money to rebuild the devastated city? The docent was quite taken aback, admitted she didn’t know the answer, and said she had never been asked that question. It’s interesting to me that most historians have as much understanding of finance as the lowliest of the Joe six-pack crowd, which includes myself, unfortunately.

You must be talking about Niall Ferguson.

Every effort has gone into hiding how the monetary system works, and everything about debt, money and banks is obfuscated to the nth degree.

Even the most basic things you take for granted aren’t true.

Banks don’t take deposits or lend money and this is quite clear in the law. It is important for the legal system to know, but they don’t really want anyone else knowing.

You are not making a deposit; you are lending the bank your money to do with as they please.

They are not lending you money; they are purchasing the loan agreement off you with money they create out of nothing.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Richard Werner explains in 15 mins.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EC0G7pY4wRE&t=3s

This is RT, but this is the most concise explanation available on YouTube.

Professor Werner, DPhil (Oxon) has been Professor of International Banking at the University of Southampton for a decade.

He has been looking into this for a long time, decades in fact.

It seems to me that the “plan” in the aoutalist world (is there another one?) is to have the paroles run up their credit card debt. The end will be some kind of Jubilee, but it might not be pretty.

“capitalist world”. God I hate posting from my dumbfone, by the end of the day, when I finally get back to my puter, it’s often too late to repair the damage.

What disturbs me a bit about much of this discussion is that it starts with the idea of distributing money, rather than doing things. After all, the idea is not that you give people money and they feel happy, but that they spend that money in such a way that demand is generated for other things, and so more activity and employment results. It’s typical of the movement in economics over the last couple of generations from a description of reality to mathematical models piled on top of each other, that it’s assumed that one thing will lead to the other. Give banks easy money and they’ll lend it to deserving investors. Give people money and they’ll spend it on consumption. Doesn’t work like that, especially at times of insecurity and fear. In Japan in the 90s there was a scheme to give people vouchers to spend which would expire after a certain date. Of course, the Japanese spent the vouchers and put an equivalent amount into savings. People may well try to pay down debts or put money aside rather than consuming. And of course much of consumption these days simply sucks in more imports.

I was born in a house which had been constructed, with hundreds of thousands of others, as part of public works projects in the 1930s. This created large numbers of jobs, and almost all the demand generated went into the local economy. If you want people to have money, it helps to give them a job, doing something useful.

You are quite right of course to say that the best way to spend money is to build something good with it. However, i think its pretty clear that the lag time for any kind of public works is so long these days that it simply can’t address the immediate need of the economy. And this isn’t even taking account the longer term effect of restrictions on construction speed.

So yes, we need both – we need cash circulating (and as you say with the Japanese example, that’s harder than it looks), and we also need New Deal style spending.

In addition to that, you have a psychological problem.

If people get money now to survive, and then get New Deal like jobs which are primarily _manual_ jobs, it still may not work. Not enough people now are open to hard manual labour, and skilled manual labour requires experience (or is dangerous). Can you create tons of clerk-type jobs so send bits of paper around, and pay reasonably ok (which is what a lot of middle class are right now)?\

So it’s not create just any jobs – because without the fundamental hard psychological experience where people are out and dry and _have_ to make a living, a lot of them will want a job that’s not massively dissimilar to what they have now.

Oh, agreed yes. But that’s the point, in a sense. There’s no quick way out of this, and rebuilding the economy (hopefully a better one) is going to take years. We need to start now.

David

You can’t build many things when you’re semi-locked in your house.

I think that paying debts is hardly a bad outcome. Paying off a credit card is maybe the best investment a person can make. Debt will eat the economy if we let it. And some people will consume stuff. Health care for example… The problem with paying people to work is one, I have no faith in current leadership to manage people efficiently (WW2 pulled us out of the Depression, not the parks improvement programs and our leaders are IMO not as honest and competent as FDR and I hate FDR), and two, until we have a structure for them to work safely we need many of them not to work. Also people need help now, even getting them a check fast enough will be a significant challenge. Setting up a functional government system to judge its citizens and provide to each according to their needs and demand from them according to their abilities sounds a lot better than it usually ends up, and the last time you want to try it is a huge crisis when everyone is rushed and confused. People won’t be able to maintain quarantine, the virus will spread, dogs and cats living together…

I understand David’s concern post-isolation — but during the enforced isolation people’s job is to STAY HOME. So pay them to stay home until the time comes to pay them to do the productive things we are going to need doing after the isolation.

Maybe, but as I said just giving people money solves nothing. They have to be willing to spend it and have something to spend it on. Then there has to be a way of getting the goods or services to the purchaser. None of that is looking very easy at the moment. I’m all for making sure people don’t starve or lose their homes, but beyond that the money is better spent directly by governments.

With nearly half of American having less than $400 for emergencies, and other surveys showing less than $1000 when you include access to credit, there are way too many bills most people have to pay to worry much about this issue. You have rent and mortgages, food, utilities, phone/internet, gas, auto insurance, maybe some unexpected car or house maintenance……

And personal debt is unproductive from a macroeconomic perspective. Having people pay down credit card and student debt is a good thing.

I’d worry a lot more about bailouts to companies who borrowed to back their shares and will use the bailouts to rinse and repeat.

There is going to be an inflation problem at least in food. I read this morning that the large corporations, ie. General Mills, are reducing their discounting and coupons for food products at grocery stores as soon as current contracts run out. This by itself will result in a sizeable increases for those items. Pressure to increase prices will also exist in other consumer categories such as garden supplies, cleaning supplies, vitamins and so on. Many products are impossible to find now. In addition, demand and prices, at least initially, will fall in areas like home improvement, theaters, travel, and so on. I couldn’t predict the mix of rising prices and falling, but it will be significant. The wealthy will have large sums to deploy, while the middle class and below will be struggling to survive. If this is a correct analysis War Bonds aimed at the wealthy, maybe with relatively favorable tax treatment, may be beneficial to sop up extra money in the system.

Fresh foods like vegetables, fruits, milk etc.are not going to restaurants and schools now. So they have to get them to grocery stores. Farmers are pouring milk down drains because many of their buyers have dried up.

I suspect processed foods will go up in price while fresh foods will stay flat in price. People will just have to learn how to use actual produce etc. again now that they have time on their hands.

I keep thinking of the Panama Papers and the trillions of offshore dollars hidden in tax havens by the rich. Would there be a way to reprint those trillions and then refuse, erase, or maroon the dollars from tax havens like the Cayman Islands? Seems like that kills two birds with one stone.

Since all US dollars, except for mere paper FRNs and coins, exist as account balances at the Federal Reserve, taxing them would be very simple – via negative interest.

The problem then is how to shelter non-rich US citizens from that negative interest and that’s why we need accounts for all US citizens at the Federal Reserve itself where they can be sheltered from negative interest to a reasonable account limit.

We also need limits to paper FRNs or a way to levy negative interest on them.

” All making up lost income does is allow people to pay their bills and leave them with the same wealth levels they would have had absent a pandemic.”

This is an example of sort of glibness you often find in MMT writings. The economy is going to contract 15% or more non-annualized due to the loss of production/economic activity under the lock-down , which is a sheer dead weight loss, which will never be made up. Just as with a disaster like a hurricane economic activity picks up in the aftermath and there is a temporary boost in GDP, which is an income flow measure, since the stock of wealth has be partly liquidated in the form of insurance payments and increases in public debt, so in the aftermath of the pandemic there might be a quick short bounce back as people return to work, followed by a long slow recovery. SO there will be a real collective loss/destruction of wealth, conventionally defined in terms of financial assets, probably in the form of a large public debt overhand, and no return to the status quo ante, neither in the real economy, which has been disrupted and will need to be restructured in terms of altered and lowered demand patterns, nor in the financial economy, where “assets” will have crashed in value. SO in the aftermath there will have to be an overall debt restructuring, an orderly write-down, and the focus of much contention will be over whose debts get reduced and whose debt will be still held good. And likewise there will be much contention over the restructuring and reform of the real economy, which has suffered at once a demand and a supply shock and on a global scale, whether in the interests of currently dominant sectors or in the direction of a more sustainable and livable economy such as the GND. But in the aftermath, the economic terrain will have been transformed and there will be no return to the status quo ante, which isn’t something that can be papered over.