By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She is currently writing a book about textile artisans.

The pandemic has caused people to spend more time in their homes, inflicting greater wear and tear on their electronics and other household appliances.

In previous right to repair posts, I’ve stressed the environmental benefits that follow both from reducing electronics waste, as well as not producing unnecessary items in the first place.

When devices wear down, consumers are now faced with the choice of replacing them, or repairing them – if a repair service can be found, to make the repair at a reasonable price.

U.S. Public Interest Research Group (US PIRG), which spearheads a right to repair campaign, earlier this month released a report, Repair Saves Families Big, on the cost savings that opting to repair rather than replace items could bring, .

Nonetheless, despite these cost advantages, according to the U.S. PIRG report:

When our older devices need repair, we might be convinced that it’s easier or better to just replace them. After all, the “new and improved” versions will be better, right? Unfortunately, that’s not always the case, and the products we buy are coming with shorter and shorter lifespans (citations omitted).

The US PIRG study emphasised two types of economic benefits to repair: repairs cost less, and repair services tend to be local businesses, whereas new purchases make the consumer yet another link in extensive global supply chains.

Cost Savings: Repair saves Money Compared to Replacemen

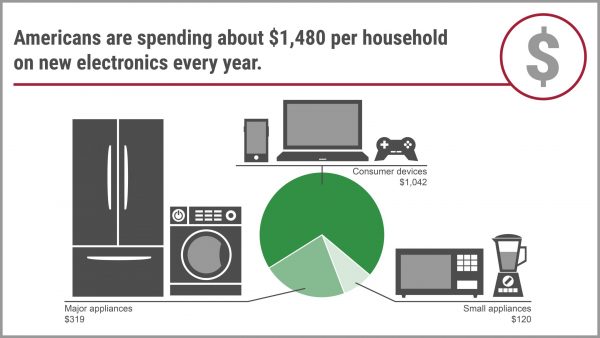

U.S. PIRG research shows that in 2019, U.S. households spent an average of about $1,480 purchasing new electronic products per year, including major and small appliances, and comprising 24 pieces of electronics. With products increasingly digital, consumers are shelling out more for products in their homes. These purchases aren’t for the long-term; rather, consumers find they are replacing electronics more frequently than in the past.

U.S. PIRG emphasizes:

Repair saves money – more than you might think. When the cost of repair inches toward the cost of replacement, it might seem like buying the new product is cheaper. But fixing the product and extending its lifespan leads to big savings.

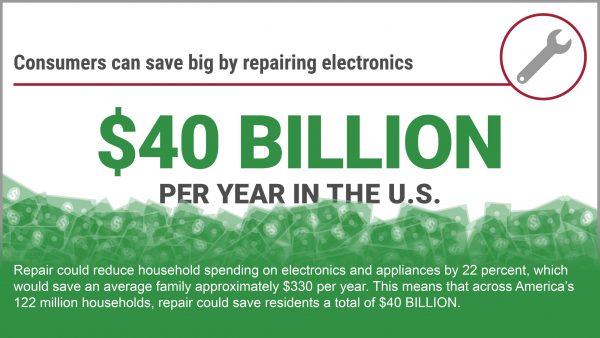

Repair could reduce household spending on electronics and appliances by 22 percent, which would save an average family approximately $330 per year.

This means that across 122 million national households,6 repair could save Americans a total of $40 billion annually.

Repair Benefits Local Businesses, Rather than Global Supply Chains

U.S. PIRG has identified a second economic benefit for repair compared to replacement: repair services are usually locally-operated, so by opting for repair, a consumer is contributing to the local economy rather than the global supply chain that produces most consumer electronics.

Repair is the More Sustainable Choice, as It Reduces Waste

Regular readers won’t be surprised to see me highlighting again that repair reduces waste, and is therefore the more sustainable choice. Per the report:

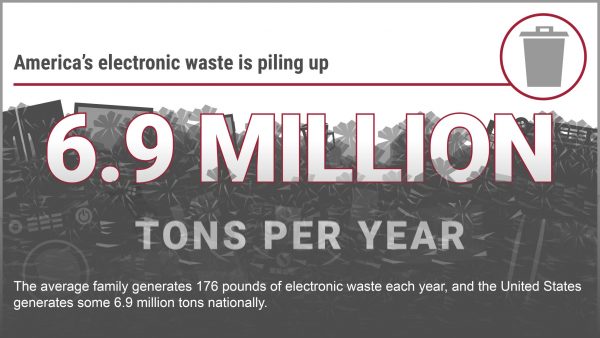

The cost of replacing broken laptops, refrigerators, and other electronic products can be burdensome, not only to family budgets, but the environment as well. The average American family generates about 176 pounds of electronic waste each year, and nationally, the United States generates 6.9 million tons of electronic waste.

When we throw out an electronic product that can be repaired, we contribute to the fastest growing waste stream in the world,4 while adding toxic elements such as lead, mercury, and cadmium into our landfills (citations omitted).

Much of this electronic waste ends up in landfills. Some is recycled. While some is reused – not so much stays stateside, but is instead exported, as there is a lively trade in used electronics. In fact, after seeing a review in The American Conservative, The Fascinating Second Lives Of Stuff, I ordered a copy of Secondhand: Travels in the New Global Garage Sale, a new Bloomsbury book, and am looking forward to starting it after I finish this post. Will report back the next time I post on right to repair.

Adopting broad U.S. right to repair provisions should mean that some items that currently end up in U.S. landfills wouldn’t. It might also mean that waste that’s currently exported – to places that presently have thriving repair cultures – would stay here as well.

Whereas reusing something elsewhere in the world is probably a better option than chucking it in a U.S. landfill, this reuse option does impose its own environmental cost: that of shipping the item to another destination. Finding new homes for items closer to their old ones would reduce the carbon footprint of that ownership transfer. But in order to do so, it’s necessary to improve the U.S. repair culture, so that items don’t have to make their way to places that can and will fix them.

“We make, use, and toss an unsustainable amount of stuff in the U.S.,” said Nathan Proctor, U.S. PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign director, when we spoke over ZOOM. “The first step towards fixing this is finding a way to use our stuff longer and therefore make less stuff. The planet can’t take it anymore – our current approach not only hits our pocketbooks today but is creating a long-term ecological catastrophe, for us and future generations.”

I’m all in favor of right to repair…but you may run into one huge problem-parts availability, where the device is either so old you can’t get parts anymore, or the parts are still being manufactured, but are on a significant backorder.

Getting old parts is indeed a problem.

I worked for 30+ years in the electronics industry, in both manufacturing and product design.

I have been in meetings where plans were made to assure a 10 year support life for a company’s product by making a “lifetime buy” of a vendor’s parts after a vendor announced they would no longer be making a component in the future.

As I recall, millions of dollars were tied up in inventory of these parts, some of which may never be used.

And some state taxing authorities tax inventories, discouraging companies from keeping a large stock of repair parts.

I do like to repair my own equipment.

I find that plastic parts frequently are difficult to get, even from established vendors (currently I need to make a plastic lever for a drill bit sharpener from the 1980’s and a worm gear for a wet grinder, also from the 1980’s).

Both products are from USA companies (Black and Decker and Delta-Rockwell) and I bought them “broken” at a deep discount.

I do find that there are many helpful people around the world offering repair advice on old obscure electronics and mechanical items.

Even some of the companies themselves try to be helpful, as they frequently respond to service questions I email to them.

One Oklahoma company sent catalog pages on a tool they last sold in the 1950’s, another New York based firm sent me an electronic copy of a service manual for a piece of test equipment from the 1980’s (and offered advice on replacement of missing components)..

But as companies go through mergers/acquisitions/bankruptcies, service information (and repair parts) can be discarded and experienced people are gone (harvested by the grim reaper or laid off/retired).

I’ve been watching my kitchen-counter-top appliances age in place — some for 50 years. With luck, they’ll be adopted when I’m not in need of such stuff any more. Thanks, Jerri-Lynn, all your posts and links today have been informative and immediately useful — much appreciated.

Synchronistically, I was just reading this article about how skill sharing timebanks have adapted to the pandemic, with an emphasis on teaching people how to repair their stuff.

https://www.shareable.net/skill-sharing-landscape-emerges/

Right to repair should also be understood as right to recovery.

I have been caught in Apple support hell for over two months with locked up iPads, BRAND NEW, that we intended for use by our parts delivery drivers.

I started setting these things up, and was then distracted by more pressing issues. When I came back to the task, I discovered I’d misplaced the passwords and pass codes associated with the devices. (I know, my bad)

Apple directed me through many hoops to no avail, I cannot get past the Activation lock, and the final solution which involved “Bring your phone close to the device” started some sort of process, but that process “Failed”.

This led me to call Apple support (All local Apple stores are closed)

Support created cases, and sent me emails requesting receipts for the devices.

Submission of receipts was followed by emailed demand for receipts again, and a more detailed description of my problems.

This story starts on October 1 2020, and as of today, I still cannot use our new Apple products.

Right to repair should also be understood as right to, and ease of recovery.

For you, and perhaps anyone who steals your iPads. I have had a Macbook stolen and it was a great relief to be able to lock it remotely, turning it into an unusable piece of metal. In the end, everything is a judgement about relative benefits, and security versus convenience is one such.

“Unusable piece of metal” instead of “preventing recovery of stolen data,” is the problem here.

On one hand, David didn’t get the laptop back, on the other, the thief can’t use it either, and will steal another one.

This is triple loss, three people will have been robbed of their ability to use their computer as a consequence of choices Apple made.

No, moralizing doesn’t fix anything here, the thief needed a computer just as David needed one, had Apple simply encrypted the data, not as-a-service to be carried out remotely – which is a potential attack vector, but as a permanent state, which required (once locally activated by the user) a USB key with encryptor-decryptor software (and un-locker post boot), then said laptop wouldn’t permit reading of the hard drive by the thief, whilst said individual could still overwrite and install his own OS and have a usable computer.

David believes to have had his privacy and sequrity protected, but any real attacker (i.e. institutional), would have prevented his MacBook from ever connecting to any network, thereby preventing remote-wipe.

The functionality is unfortunately just a classist attack on those who can only ever come into possession of an Apple device via theft, it doesn’t prevent real information attacks, and it doesn’t protect Apple hardware “owners.”

The existence of this capability does however, enable Apple (and many other entities, not just governments) to remote wipe and disable users data and devices.

I’d say there are way bigger concerns here than the odd thief here and there, both for users and for institutions and the society as a whole. (Just a fair warning.)

This is the first time I’ve seen a commenter top a post by David, and it does provide a great value too with expanding the perspective.

Thank you.

Wow, that’s terrible support from a so-called ‘leading edge’ company. My last tangle with Apple support was bad, but not that bad, not 3+ months bad.

You’ve probably already searched/queried/checked all the online how-to sources like lifewire and howtogeek etc and youtube for a fix. Here’s one thing I’ve discovered about using a search engine query to find fixes for a computer problem: If I query/ask/search a how-to during normal working or waking hours I often get no good answers. (Where normal waking hours are say 6am-midnight local time.) However, if I query the same search at say 2am-4am I get good links that have answers that resolve the problem I’m working on. Passing this tip along for whatever it’s worth – which is probably only as much as you paid for it. / :)

Just a note, for repair to be the sensible option it is also absolutely necessary that devices last for a long time, not just as a total time, but also as a long time before the first failure that would necessitate a repair service.

Any repair service is a disruption to the user and, if too disruptive, too costly, or too often occurring (i.e failures that happen soon after purchase), it may (“will”) prompt users to repurchase a new (if identical) device.

We need to define some time periods in the body of law:

– a minimum amount of years within which no device may fail

(for example: 5 years),

– a minimum amount of years covered by free warranty (with free temporary replacement during service, and free logistics) (for example: 10 years – remember this is minimum we are talking about),

– a minimum of years of a production-run plus a minimum of years of spare parts availability

(for example: 40 years).

Before anyone starts rolling their eyes: the F-15 Eagle first entered service in 1976 and its Soviet predecessor, Mig-25 in 1970; both airplanes (in their modernized variants) are still in use.

The expected time-of-service of a complex weapons platform is 30 years (with maintenance and service-life extensions and upgrades), production, as you can see, can run for more than 50 years; if the famously inefficient and corrupt MIC contractors can make that happen, then civilian, low-stress, low-power appliances could, and should, be made to last for ever.

——————————————–

Repair, as an issue on its own, is a distraction, as most of the failures and breakdowns shouldn’t be happening, and certainly not on new devices (i.e. less than 5 years old).

Well said. A well-designed product using appropriate materials doesn’t break early or often.

We’ve allowed our expectations about quality and durability to be eroded; we allow ourselves to buy based on price instead of value, and we do so because we expect the product to be obsoleted. This is especially the case with electronic devices.

I buy quality, and I buy modular, parts-swappable designs I can repair myself.

With respect to replacement parts availability, this is one area where 3D printing and low-cost (or free) CAD/CAM software – used at the household level with parts manufacturing done on-line via regional facility – and sold on-line via repairClinic.com and its like may provide a very attractive home-based income for people with engineering and manufacturing background.

That means machines never have to die due to lack of spare parts.

In the no-so-distant future, we’re going to have to elevate materials reclamation over functionality if we’re ever to reduce the materials sourcing load on the planet. That means we’d design for materials reclamation first, functionality second.

Most manufacturers and most customers would balk and not buy the product, because it would “do less” and maybe “cost more up front”. But if I can turn the end-of-life product over to a recycling center and recover 10-30% of the purchase price, that would affect my purchase decision.

If the product design also allowed for field upgrade and repair….that would induce me to buy it.

Depends what product. I bought a $50 Motorola phone a few years back. (Android 4.4?) It still works. What would that phone cost if they had to keep parts on had for a decade?

On the other hand, about 18 months ago, in small town on the edge of the Sahara Desert I watched this guy fix someone iPhone 7 in about 30 minutes that the owner claimed they had not been able to get fixed in either Canada or the US.

Usually after you run out of the original stock of aircraft parts you end up cannibalizing aircraft like the military does. Airlines often rob parts off of ordered aircraft that are on the production line if a part is not in stock, can’t be borrowed from another airline or not available in a boneyard. New not in stock aircraft parts have a six month lead time after being ordered if a vendor is still available to manufacture them.

A recent article from about five weeks ago posted here at NC about the US military having problems fixing their aircraft, with lack of parts being part of the problem: 224 killed, 186 military aircraft lost. Pilots worry about being ‘the next accident’

I’d like to add, isn’t one of the incentives for businesses to not keep a lot of parts in stock due to being taxed on the value of the inventory? I’ve had fights in the past when I pushed to harvest as much as I could off of aircraft that were a hull loss and was told we couldn’t afford that many parts in stock, even when the quantity would be 1.

Another struggle was stock people trying to purge parts that are unique and out of production but only issued every four or five years. They were using PCs and one or two year windows on their spreadsheets. Sometimes all this efficiency costs a lot of money.

I love repairing electronics, since the start of COVID I have done: new tubes and bias in an old guitar amp, new battery in my fiancé’s iPhone, fixed the backlight on a friends TV, new battery/switch/fixed wiring on a veterinary ultrasound blood pressure meter, fixed a small water leak in a veterinary dental machine, and fixed the power supply in a phono preamp.

Probably a big caveat is that I am an electrical engineer, however I think only the phono preamp really required any real electrical knowledge. The rest of those things could be done with either guides, or a little ingenuity (do any of the parts look burned? Where is the leak coming from? Etc). I’ve found that most people seem to shy away from repair because they are afraid of breaking something but in my experience, it is hard to do permanent damage as long as you are careful and take your time. Good light, appropriate tools (not expensive though), good eyesight and a steady hand really help. For the veterinary stuff, support and spare parts are readily available because those are actually built to last. Phone parts can be bought online. Stuff like TV parts or old audio gear can be harder and it helps to be able to identify board numbers and electronic components. Overall though, fixing your own stuff is hugely rewarding and I would encourage anyone with a bit of patience and curiosity to give shot. Good beginner projects are things like phone batteries, screens and buttons and info online is plentiful if you run into problems.

Another not insignificant benefit of the ability to successfully repair stuff is that one’s adulr, home-owning kids may see one in a new, more “enlightened” light.

When that text comes. “Dad the insert appliance here- has broken “. It’s useful to be able to offer hope lol……..

Whatever you do, don’t donate computers to Goodwill. They partner with Dell which buys them for pennies and trashes them so as to protect its new computer market. Salvation Army and other local charities do ok, although they usually can’t repair items.

However, if you search YOUR local area for “computer repair trade recycle buy” you’ll get a list of places that recycle computers and electronics, sometimes for cash, that repair and resells them.

Here are two we have used Renew Computers in Marin County, California

https://renewcomputers.com/refurbished-computers/.

and our favorite, Recycle My Machine, in West L.A.

http://www.recyclemymachine.com/

If you lust after the latest consumer electronics, circa 2015, more or less, these places have them for 1/10th the price as new, warranteed and as good as new.

Last month I replaced the battery in my perfectly adequate 4 yr old (bought used) moto g4 phone using trivial instructions from ifixit. Now I can use it for at least a day on battery. However, it is stuck on android 7.0 which doesn’t bother me but it is completely insecure because Lenovo hasn’t released kernel patches since April 2018.

So fixing hardware is not useful if the software stays unpatched. I looked at a moto g power but the battery is completely sealed. I want Linux phones to succeed, provided battery can be replaced.

Thanks for this article.

Here’s a link to one of my favorite digital electronics ‘fix it yourself’ sites:

https://www.ifixit.com/Right-to-Repair/Intro

The menu item ‘Fix Your Stuff’ has lots of good step-by-step repair guides for digital phones, tablet computers, laptops, desktops, ipods, game consoles, etc. A lot of fixes are pretty easy for anyone. The repair guides list difficulty level of the repair steps and show pictures for each step, so you can judge whether or not a given repair looks like something you’d want to tackle.

Jeri-Lynn —

Great post — thank you! You might want to fix the typo in the following phrase “I’ve stressed the environmental benefits that follow both from reducing elections waste”

Freudian slip, I’m sure — but also apt. There would be great benefits of many kinds from reducing elections waste, I’m sure ;-)

Fixed it – thanks! Next up: reducing elections waste – indeed a worthwhile project. But not nearly as easy to fix as that typo.

The best effect of “Right to Repair” (R2R) is that the buyer has more leverage to force the seller to offer real improvements in new items, rather than just crappified glitz marketing.

Remember Fight Back with David Horowitz? We are in desperate need of a populist consumer advocacy that runs with this idea.

Why don’t we invest in more ways to recycle? “Turn in your used cell phone, computer, etc, etc”.