Yves here. It’s not too hard to notice when the producer of a niche product you like gets gobbled up by Big Food and you hope nothing much will change. But that’s only one facet of the increased concentration in the industry. As this article explains, it has reached the point where some incumbents have pricing power. Even though this article focuses on the impact on rural and lower income households, one place where the effect is visible is in organic products, which sell at a 30% or greater premium to conventional versions. Yet I’m told organic food generally costs only 5-10% more to produce. And why should organic products placed out of the reach of lower income households? Shouldn’t they be able to afford food with fewer/no chemicals and additives?

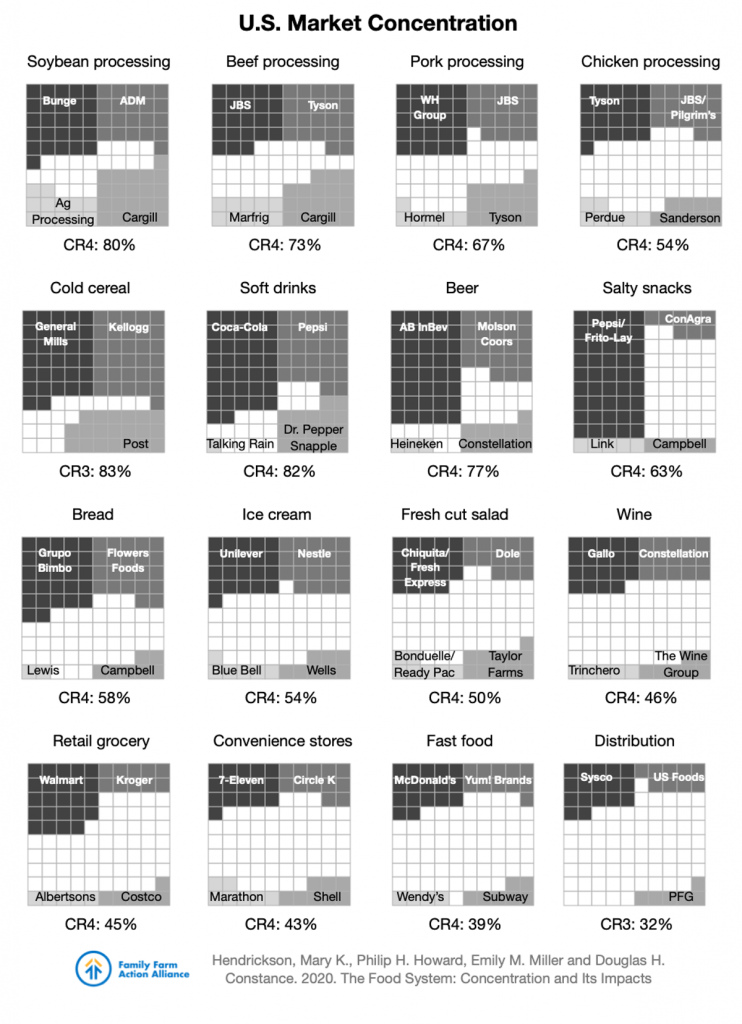

You’ll see from the article how many broad food product categories are subject to enough concentration to move prices, like bread and beer. The authors push for more localized production as a way to combat the power of Big Food.

By Philip H. Howard, Associate Professor of Community Sustainability, Michigan State University and, Mary Hendrickson, Associate Professor of Rural Sociology, University of Missouri-Columbia. Originally published at The Conversation

Agribusiness executives and government policymakers often praise the U.S. food system for producing abundant and affordable food. In fact, however, food costs are rising, and shoppers in many parts of the U.S. have limited access to fresh, healthy products.

This isn’t just an academic argument. Even before the current pandemic, millions of people in the U.S. went hungry. In 2019 the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated that over 35 million people were “food insecure,” meaning they did not have reliable access to affordable, nutritious food. Now food banks are struggling to feed people who have lost jobs and income thanks to COVID-19.

As rural sociologists, we study changes in food systems and sustainability. We’ve closely followed corporate consolidation of food production, processing and distribution in the U.S. over the past 40 years. In our view, this process is making food less available or affordable for many Americans.

Fewer, Larger Companies

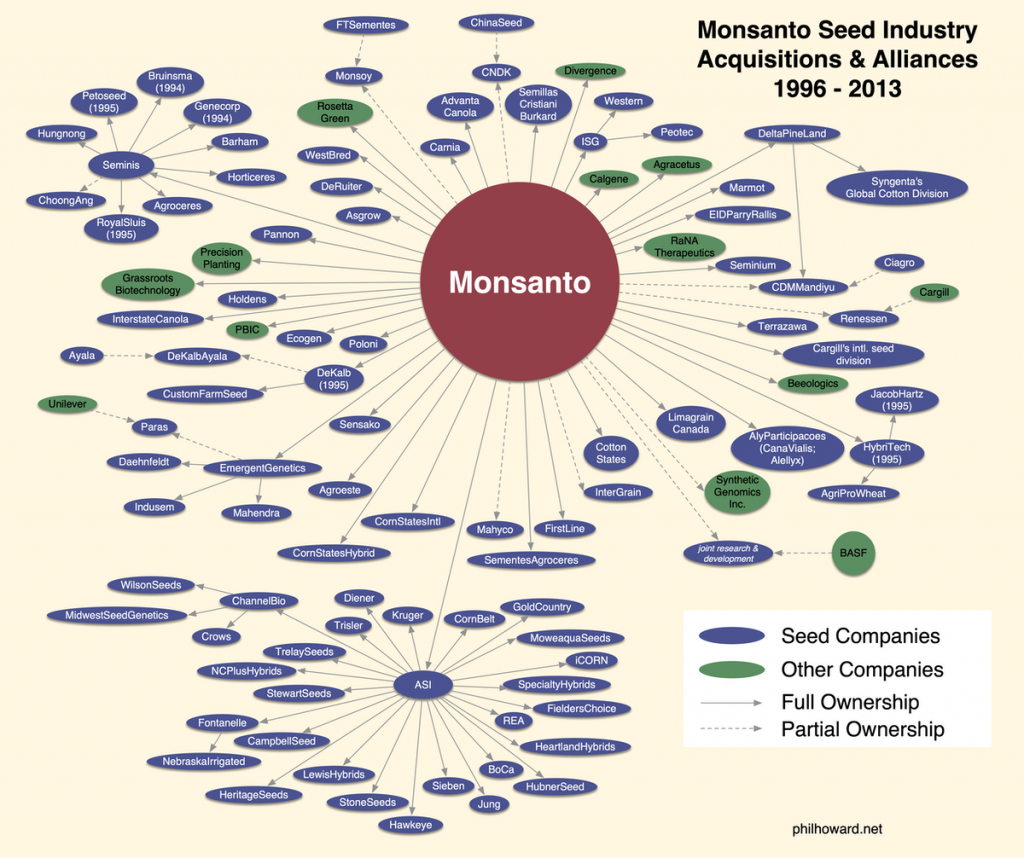

Consolidation has placed key decisions about our nation’s food system in the hands of a few large companies, giving them outsized influence to lobby policymakers, direct food and industry research and influence media coverage. These corporations also have enormous power to make decisions about what food is produced how, where and by whom, and who gets to eat it. We’ve tracked this trend across the globe.

It began in the 1980s with mergers and acquisitions that left a few large firms dominating nearly every step of the food chain. Among the largest are retailer Walmart, food processor Nestléand seed/chemical firm Bayer.

Some corporate leaders have abused their power – for example, by allying with their few competitors to fix prices. In 2020 Christopher Lischewski, the former president and CEO of Bumblebee Foods, was convicted of conspiracy to fix prices of canned tuna. He was sentenced to 40 months in prison and fined US$100,000.

In the same year, chicken processor Pilgrim’s Pride pleaded guilty to price-fixing charges and was fined $110.5 million. Meatpacking company JBS settled a $24.5 million pork price-fixing lawsuit, and farmers won a class action settlement against peanut-shelling companies Olam and Birdsong.

Industry consolidation is hard to track. Many subsidiary firms often are controlled by one parent corporation and engage in “contract packing,” in which a single processing plant produces identical foods that are then sold under dozens of different brands – including labels that compete directly against each other.

Recalls ordered in response to food-borne disease outbreaks have revealed the broad scope of contracting relationships. Shutdowns at meatpacking plants due to COVID-19 infections among workers have shown how much of the U.S. food supply flows through a small number of facilities.

With consolidation, large supermarket chains have closed many urban and rural stores. This process has left numerous communities with limited food selections and high prices – especially neighborhoods with many low-income, Black or Latino households.

Widespread Hunger

As unemployment has risen during the pandemic, so has the number of hungry Americans. Feeding America, a nationwide network of food banks, estimates that up to 50 million people – including 17 million children – may currently be experiencing food insecurity. Nationwide, demand at food banks grew by over 48% during the first half of 2020.

Simultaneously, disruptions in food supply chains forced farmers to dump milk down the drain, leave produce rotting in fields and euthanize livestock that could not be processed at slaughterhouses. We estimate that between March and May of 2020, farmers disposed of somewhere between 300,000 and 800,000 hogs and 2 million chickens – more than 30,000 tons of meat.

What role does concentration play in this situation? Research shows that retail concentration correlates with higher prices for consumers. It also shows that when food systems have fewer production and processing sites, disruptions can have major impacts on supply.

Consolidation makes it easier for any industry to maintain high prices. With few players, companies simply match each other’s price increases rather than competing with them. Concentration in the U.S. food system has raised the costs of everything from breakfast cereal and coffee to beer.

As the pandemic roiled the nation’s food system through 2020, consumer food costs rose by 3.4%, compared to 0.4% in 2018 and 0.9% in 2019. We expect retail prices to remain high because they are “sticky,” with a tendency to increase rapidly but to decline more slowly and only partially.

We also believe there could be further supply disruptions. A few months into the pandemic, meat shelves in some U.S. stores sat empty, while some of the nation’s largest processors were exporting record amounts of meat to China. U.S. Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Cory Booker, D-N.J., cited this imbalance as evidence of the need to crack down on what they called “monopolistic practices” by Tyson Foods, Cargill, JBS and Smithfield, which dominate the U.S. meatpacking industry.

Tyson Foods responded that a large portion of its exports were “cuts of meat or portions of the animal that are not desired by” Americans. Store shelves are no longer empty for most cuts of meat, but processing plants remain overbooked, with many scheduling well into 2021.

Toward a More Equitable Food System

In our view, a resilient food system that feeds everyone can be achieved only through a more equitable distribution of power. This in turn will require action in areas ranging from contract law and antitrust policy to workers’ rights and economic development. Farmers, workers, elected officials and communities will have to work together to fashion alternatives and change policies.

.@USDA is seeking members for a new advisory committee on urban agriculture, part of a broader effort to focus on the needs of urban farmers. And yes, self-nominations are welcome! https://t.co/7dDhMLlvwJ pic.twitter.com/sF1dkPYkhS

— Farmers.gov (@FarmersGov) January 28, 2021

The goal should be to produce more locally sourced food with shorter and less-centralized supply chains. Detroit offers an example. Over the past 50 years, food producers there have established more than 1,900 urban farms and gardens. A planned community-owned food co-op will serve the city’s North End, whose residents are predominantly low- and moderate-income and African American.

The federal government can help by adapting farm support programs to target farms and businesses that serve local and regional markets. State and federal incentives can build community- or cooperative-owned farms and processing and distribution businesses. Ventures like these could provide economic development opportunities while making the food system more resilient.

In our view, the best solutions will come from listening to and working with the people most affected: sustainable farmers, farm and food service workers, entrepreneurs and cooperators – and ultimately, the people whom they feed.

(Long time reader, first time commenter!)

Very important stuff. I’ll note the pandemic re-emphasized the importance of what I think of as Local Resiliency – the ability of local economies, good services, etc. to function. Here in Boston, during the early phase of the pandemic getting food (don’t even dive into the TP insanity!) from the established supermarket chains was difficult but I found a number of local farms, food producers and such that started creating and ramping up home delivery which in my case was a godsend. In the past, I would often buy from local farmer’s markets but this just made me even more loyal and very much value them because they worked when the official deep supply corporate chains simply weren’t.

Great post. Great comment. Agree completely.

Tyson has itself become the meet packing behemoth from buying Iowa Beef Packers (IBP) and other smaller packers, and in 2019 was in talks to buy Foster Farms in California. Not sure how that deal came out.

The local butcher sells out twice as fast as before and can’t keep enough in his case, even with the grocery stores full. Great to see. And their prices are the same as the grocery store without the three things on sale this week from Smithfield or Tyson. He buys all of his meat at local auction twice a week.

Exactly right. That was and is our experience in San Antonio; establishing connections with local farmers/ranchers and buying their products directly avoids the lines and middle men of big grocery stores. We have a local pork producer here who just opened a butcher shop. Growing your own vegetables and possibly some chickens is another level of self-sufficiency. I haven’t bought any sort of salad greens in about a year and a half now. Very empowering!

Any theories about why the bumblebee guy got jail time? Lack of jail time for corporate malfeasance (opiates, fraud, etc) has been the norm. Is it an industry specific thing, with tuna makers missing the social connections with regulators? Is it a one-off, as a result of a particular prosecutor? or is was the conduct just too egregious? according to the nyt article:

“The conspiracy scheme began in or around November 2010 and went on until December 2013, according to court records. Mr. Lischewski and his co-conspirators tried to go undetected by the authorities by talking in code when referring to one another, meeting in remote locations and providing misleading justifications for prices.”

Hardcore price fixing is one area of white collar crime where the authorities tend to get serious. I suspect it’s because it’s such an obvious violation of the law (Sherman Act sec. 1) with widespread and readily understandable effects (higher prices, usually).

Correct. ADM execs went to prison for price-fixing in the lysine, citric acid, and other markets.

https://www.justice.gov/archive/atr/public/press_releases/1996/1030.htm

https://www.iatp.org/news/adm-executives-convicted-of-price-fixing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Whitacre

Price fixing is also one of the few areas of white collar crime in which the authorities actually empathize with the victims. I suspect it’s because they’re one of ’em!

If hyperbole helps;

Slap around a little guy in front of a cop and the cop will probably break it up and if you’re uncooperative, you might go to jail.

Slap the cop around and the cop will probably break something and if you survive, you’re going to jail!

No to take anything ever away from all the workers on the front lines, first responders and all. doing some incredible work in this pandemic, but is there a more “essential” worker than the a farmer? Day after day, week after week, year after year? Humans are capable of so much, but nobody does ANY it of they are starving. Support your local farmer, the little guy and gal, in every way possible ( and I am not talking abut the corporate behemoths, they will always be fine). If there was ever a system that demands diversity and lack of concentration, from cattle to crops. it is the food industry.

(Written by the proud father of a daughter that has started a small farm and been in farming all her life).

This is how our form of Capitalism works.The big guys stomp out competition by buying up competitors. We used to enforce anti trust laws. That appears to no longer happen. Companies have a free hand to merge whenever they wish. Where I live , in the summer you can easily buy locally produced vegetables.The price is about the same and the quality is much better. When you go into a store and see all of the different products it make you think you have a lot of choices. If you look at the label you see that the same company produces most of them. That means there is really not much competition.Gasoline is another product without much competition.In my area every gas station charges exactly the same price.

Detroit may have become able to succeed in growing urban farming in part because land was available . . . thanks to a huge population decline which in turn was not unrelated to the process known variously as “urban renewal”, “slum clearance”, and a few other NSF-family-blog names.

Detroit became the fourth-largest city in the US around the 1920 census, with just under a million people. Its peak population came in 1950 at just under 1,850,000; it was still fifth largest. But since then, Detroit has lost almost 2/3 of its population and is estimated to be in 24th place.

https://www.biggestuscities.com/city/detroit-michigan

The “de-housing” of the mid-20th Century was a significant factor in this — as indicated by the figures here:

http://www.detroits-great-rebellion.com/Urban-Renewal.html

saying that 41 renewal projects active in 1967 cleared 11,000 acres of land, about 12% of the city’s area.

The greatest indictment of Big Food is that people who eat nothing other than manufactured food products can actually die of malnutrition — not from a lack of calories, but from foods that have had any natural nutritional value wrung out of them, causing morbid obesity, diabetes, heart disease and cancer. Yes, ADM, Kellogg, Nestle, et al, I’m looking at you.

And tragically, it’s these very foods that are most likely to be distributed by the food bank industrial complex.

The Big Food “food” you refer to is sometimes called “sh-tfood” by some.

Hopefully, some of the new food-bank clients ate better before they got food-bank poor. If so, food bank food will keep them alive long enough to where they hopefully become better-food post-poor again. Maybe by luck, maybe by policy.

Meanwhile, if currently non-poor people want the food-bank poor to have better quality food to eat, non-poor people will have to figure out how to give better quality food to food banks in a way that food banks can accept and handle and give back out to their food-bank-poor clients.

And in fact, perhaps food banks should also give out multi vitamineral supplements and metamucil to those among their clients who understand the need for certain nutrients and fiber.

I think that everything said in the article and the post is 100% true. Big companies are actually hurting our economy by narrowing down the places where all of the food is produced for the American people. The little bit in the post about how sometimes the same manufacturing companies/packing companies will produce the same food for different companies, but just put different labels on them, shocked me. The evidence shows that big corporations are not only hurting the economy because the prices of food are too high but hurting the American people as well who need that food to survive especially during the Pandemic. It should not be so expensive to buy food and to buy good food from smaller companies, just because the big companies want to become as big as possible. All they care about is the money, not the American people.

Trying to get organic food these days is very hard and it is very expensive. The reason for this is because big companies have made it so easy to get processed foods. The fact that there are becoming fewer companies but the ones that survive are all large ones scares me because they can really control what people eat and if they wanted to could just sell all processed foods to us at a very high price which is what they are doing now. Change has got to come so that people can save money and eat healthier. The economy would benefit from the change as well, allowing for more companies to produce foods so that people have more options while shopping. Big companies would not be able to control everything anymore which is very good for our economy.

No, you missed the key point. It is NOT all that much more costly to produce organic products, just 5% go 10% more. The food companies charge more because organic producers are fragmented (at least until they are bought up by Big Ag) and so can’t end run the distribution process, and their wares get marked way up because the middlemen know middle class and affluent customers will pay way more for organic.

I wonder what percent the food-cost is of the average person’s cost-of-living budget in America as against in other countries. I tried to find it on the internet, but the search prevention engines frustrated my feeble efforts.

So I don’t know whether the average American spends a higher or lower percent of herm’s personal spending on food than what the average other-country-citizen spends.

You fix concentration at the distribution point.

We must enact laws that mandate shelves be stocked,

for example, with produce originating from 25% local county, 25% regional, 25% national sources. massage numbers as appropriate.