Yves here. This post provides a very informative, long view of the shifting status of women in society. However, it is silent on how changes in the gender gap came about. In the last 100 years, women getting greater reproductive control was central to eing able to enter the workforce in large numbers. They were less hostage, particularly if they were single, to pregnancy upending their lives. And the opening up of more career prospects, particularly jobs with higher pay, meant it was attractive for women to defer child-bearing, be less dependent on a man when they did have children, and not make an enormous economic sacrifice if they stayed single.

I know very little about the standing of women in ancient society. But Michael Hudson has mentioned that women ran (and it sounded as if they were owner/managers) of beerhouses, and they were important back then.

But I hate to say, women are likely to remain subject not just to bearing more of the cost of childrearing than men, but also to their smaller size. Harvard Business School tracks lots of data about its graduates. The single variable that best explains how much they earn is height.

By Arash Nekoei, Assistant Professor of Economics, IIES-Stockholm and Fabian Sinn, PhD student in Economics, IIES-Stockholm. Originally published at VoxEU

The international differences in women’s status are striking. When and where did those differences first emerge? Is women’s status improving everywhere today so that we expect global gender equality eventually? This column uses data from the Human Biological Record to explore women’s status over the last 5,000 years. The records show no long-run trend in women’s share in recorded history. Historically, women’s power has been a side-effect of nepotism: the more important family connections, the higher the women’s share. But self-made women began to rise among the writers in the 17th century before a broader take-off in the 19th century. Exploring these captivating and yet unanswered questions teaches us about the future of women and other emancipation movements.

Finding my path among a crowd of cyclists on an April morning, the frosty weather reminds me that Stockholm lies at sixty degrees north. I am not surprised that most of the cyclists around me are women. But in fact, I should be shocked if I were to think in a historical and international context.

Women have biked a long way to get here. They even adapted their clothing style to take advantage of the independence that this new, cheap mode of transport offered at the turn of the 20th century. Susan B Anthony, the American women’s rights activist, wrote in 1896: “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world” (Shrock 2004, Macy 2017).

Even in Sweden, the most gender-neutral country in Europe, just a few decades ago the cyclist crowd would be majority male, like most cyclist crowds in the world today (EIGE 2020). Cycling is, of course, only one dimension of women’s status, which range from legal rights, informal customs, to representation in positions of power.

What are the historical roots of these international differences? How far back do we need to go in history to find the root of divergence? Should we expect a convergence eventually?

Such a long-term and global understanding of women’s history not only improves our understanding of the past but, importantly, teaches us about the future of women and other oppressed groups and their (potential) paths of emancipation. As the mathematician Joseph Fourier wrote 200 years ago, “the degree of emancipation of women is the natural measure of general emancipation”.

The rise of women’s status has come with many struggles. First-wave feminism fought for women’s property and voting rights, leading to enfranchisement in developed countries during the 20th century. Starting in the 1960s, second-wave feminism targeted workplace and legal inequality. Following Generation X’s third wave in the 1990s, today we are living through the fourth wave of feminism as the spotlight of #MeToo justice reached men of power from all walks of life.

But was it really the case that half of the world population were repressed for the entire history of humankind, leaving half of the total brainpower unused? We had doubts from the beginning, as many outstanding women throughout history pop into my head.

What about Sappho? What about Joan of Arc? Female rulers held power in almost every civilisation, from Hatshepsut (the mighty pharaoh in 15th century BCE) to more than a millennia later when Cleopatra VII reigned over Egypt, to the “queens era” of Europe, usually dated from the 14th to 18th century CE, with prominent queens like Elizabeth of England and Christina of Sweden (Monter 2012).

Despite the debate on gender balance being front and centre in many societies, most research has focused on case studies of a few exceptional women or women’s status in a specific region in a particular era. Although these provide valuable insights, we still lack a unified view of how women’s status evolved over time and across countries.

Our work seeks to address these questions systematically and quantitatively and provide a unified view of how women’s status evolved over the entire 5,000 years of human history.

Approach

The progress on these fundamental questions has been impeded by the lack of a consistent and comprehensive dataset covering time and space. In recent work, we built such data, the Human Biographical Record (Nekoei and Sinn 2021b). The Human Biographical Record is part of a larger project, the Human Record, where we construct and provide to the research community datasets like the Human Biographical Record using two components.

First, crowd-sourcing produces the largest voluntary collaboration in human history through Wikipedia and Wikidata. Second, machine learning transfers all this information to datasets like the Human Biographical Record, where we can use modern statistical methods to uncover historical patterns.1

As part of this research agenda, we attempt to write a quantitative history of women over the last 5,000 years (Nekoei and Sinn 2021a). This is an exercise in long-run quantitative history in the spirit of École des Annales (social history). We measure the female share of people at the top of the social hierarchy in each era as a proxy for women’s status. This measure echoes how we today use the female share in almost all our debates on women’s emancipation.

Using the Human Biographical Record, our focus is on a fixed share of each generation (top 1 percent mille), to allow comparison across time and space. We use the fact that around 1% of Human Biographical Record’s entries have an entry in traditional encyclopaedias such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica. We first predict the likelihood of appearing in a traditional encyclopaedia, then extrapolate to rank all seven million entries in the Human Biographical Record.

Findings

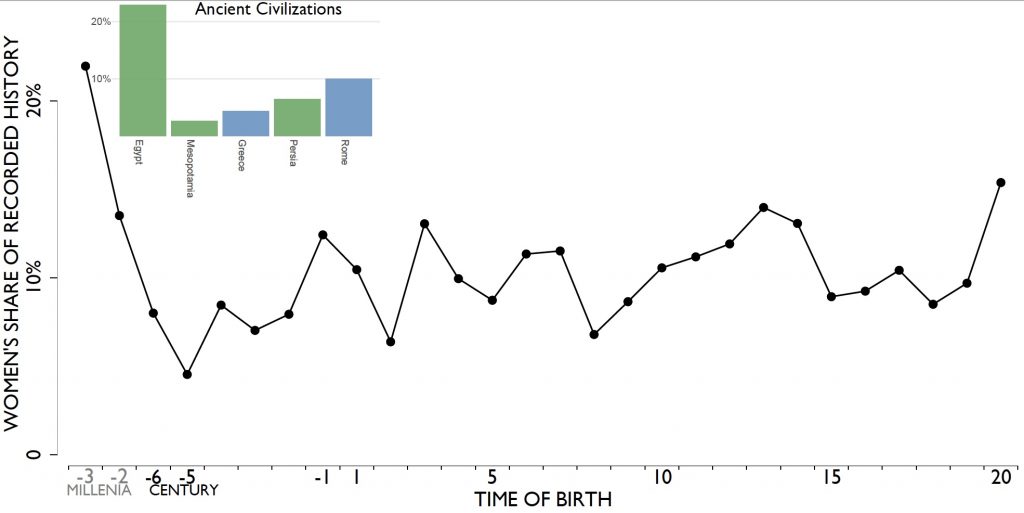

To our surprise, we document no long-run trend in the women’s share at the top when analysing 5000 years of recorded human history (Figure 1). While women’s share fluctuates around an average of 10%, the main positive outlier is the third millennium BCE, driven by a high women’s presence among Ancient Egypt’s observations in the Human Biographical Record and echoes Egyptian women’s equal rights to men. Women could initiate divorce, own and transmit property, receive an equal inheritance, and even achieve immortality (Lesko 1998, Bridenthal et al. 1998, Hughes and Hughes 2001, Johnson 2002)!

Figure 1 Women’s share at the top of social hierarchy over history

This finding puts women’s contemporary struggle for equality in historical perspective. Women’s emancipation is not a contemporary concept, but the world had actually progressed quite far already a long time ago, before regressing.

But the modern rise of women has a distinct and important feature. A closer look at the Human Biographical Record individual-level data reveals that for most of history, women who became part of the elite were either born into influential families or married into them. We show that women’s power has been a side-effect of nepotism: the more important the family connections, the higher the share of women at the top.

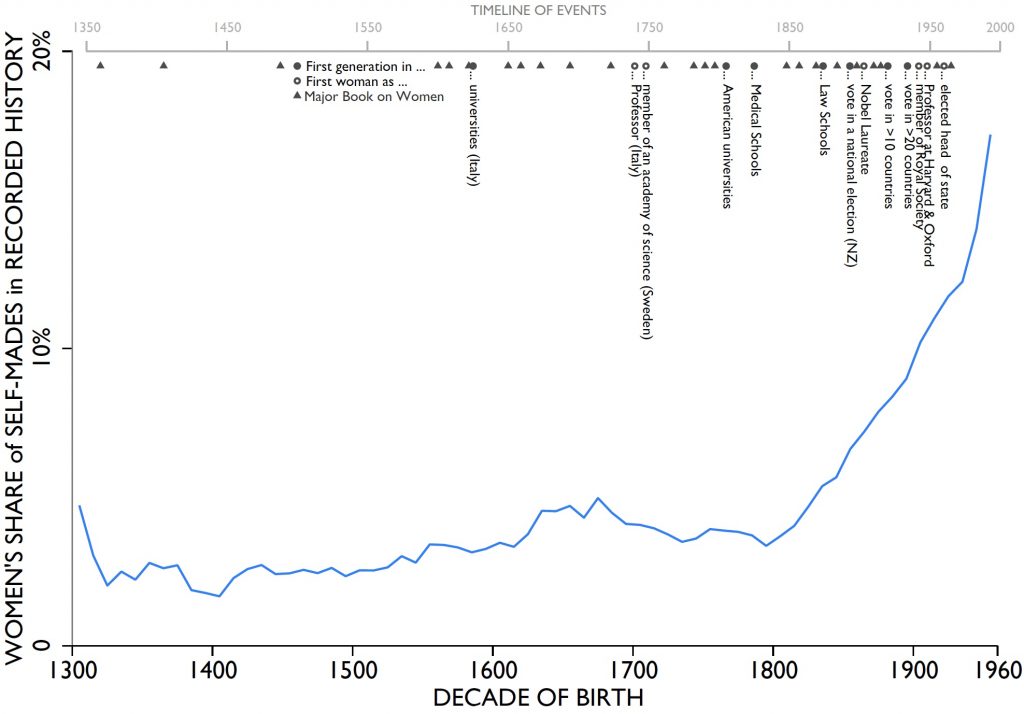

This relationship is present across time (in the time series) and geographies within a period (in the cross-section), but it slowly begins to break down in recent centuries. Indeed, Figure 2 shows a rising prevalence of women who were not born into families or married to males with power and fame, a group we call ‘self-made’. But where did this group come from?

Figure 2 Women’s share of ‘self-mades’ over history

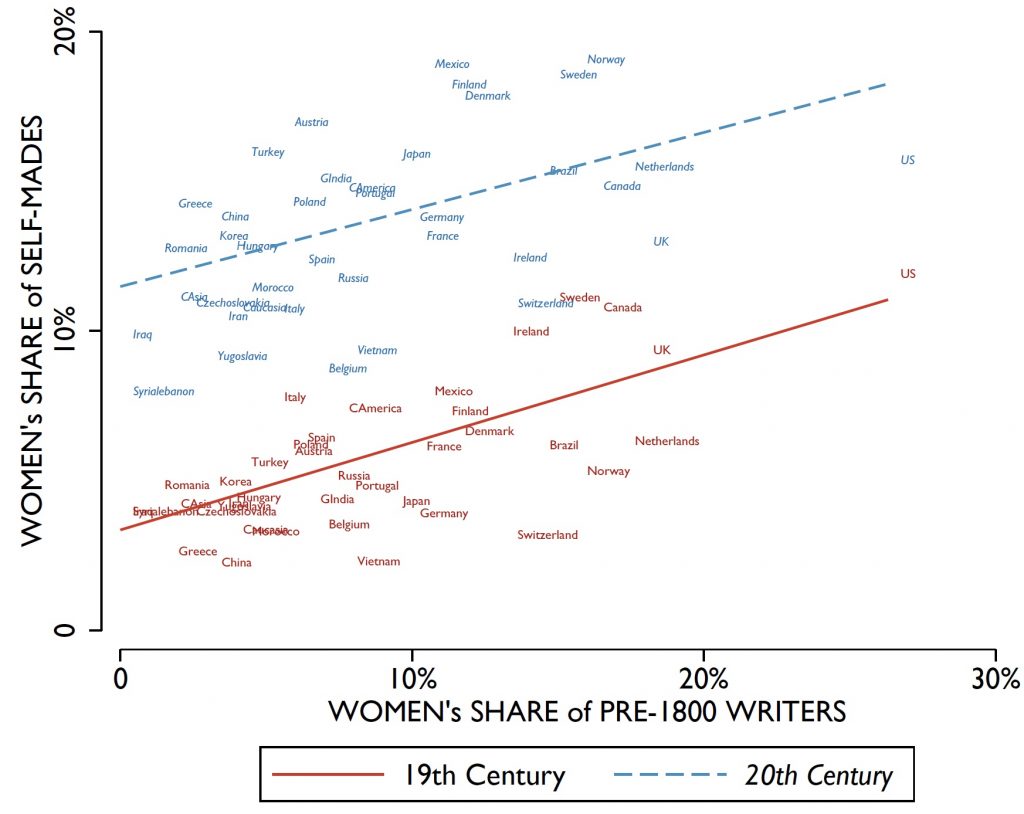

The first rise in the share of women among self-mades is recorded among writers and poets born between 1620 and 1660. It reflects the birth of ‘the feminine reading market’ in Protestant Europe (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Women’s share of writers over history

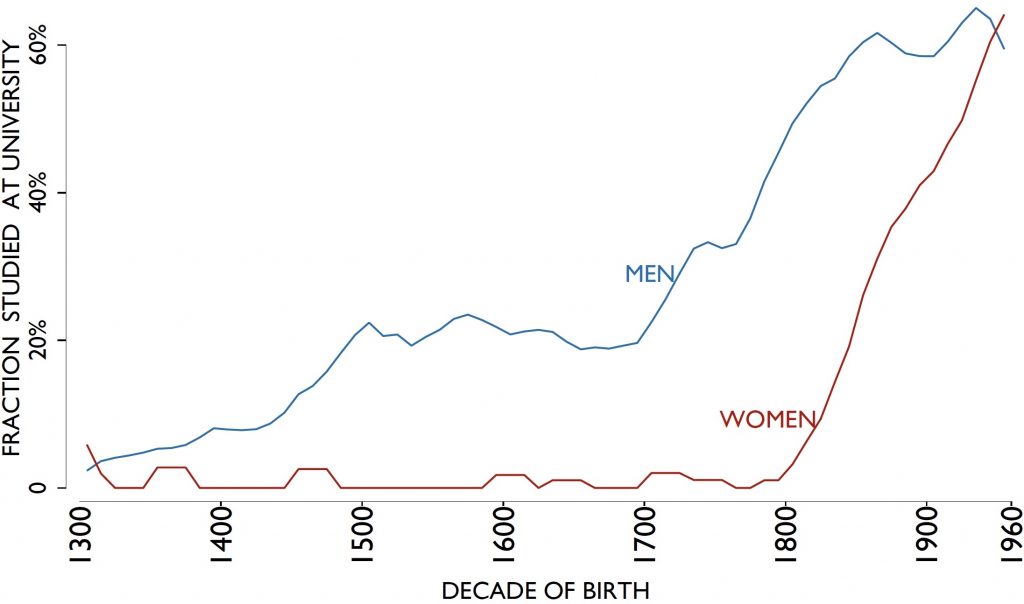

This market emerged in the context of increasing the literacy and purchasing power of women. The women writers and poets who supplied this market were educated by informal ‘household academies’, as universities during this period were closed to women (Figure 4). These highly educated women flourished in new informal public spheres: salons and the Republic of Letters.

Figure 4 Fraction studied at university over history

During the same period, both the marriage and labour markets awarded a higher return to women’s education. The new feminine reading market encompassed new genres, such as the novel, in a new language: vernacular, not Latin. The book market structure with many small buyers and less guild presence may have played a significant role in creating a space for self-made women to flourish.

A century and a half later, a broader take-off of self-made women started with the 1800 birth cohort – first among artists and scholars, followed by elected politicians, and finally appointed politicians. There is no sign of a slowdown in the rate of progress, and self-made successful women have become a ubiquitous phenomenon in the recent period.

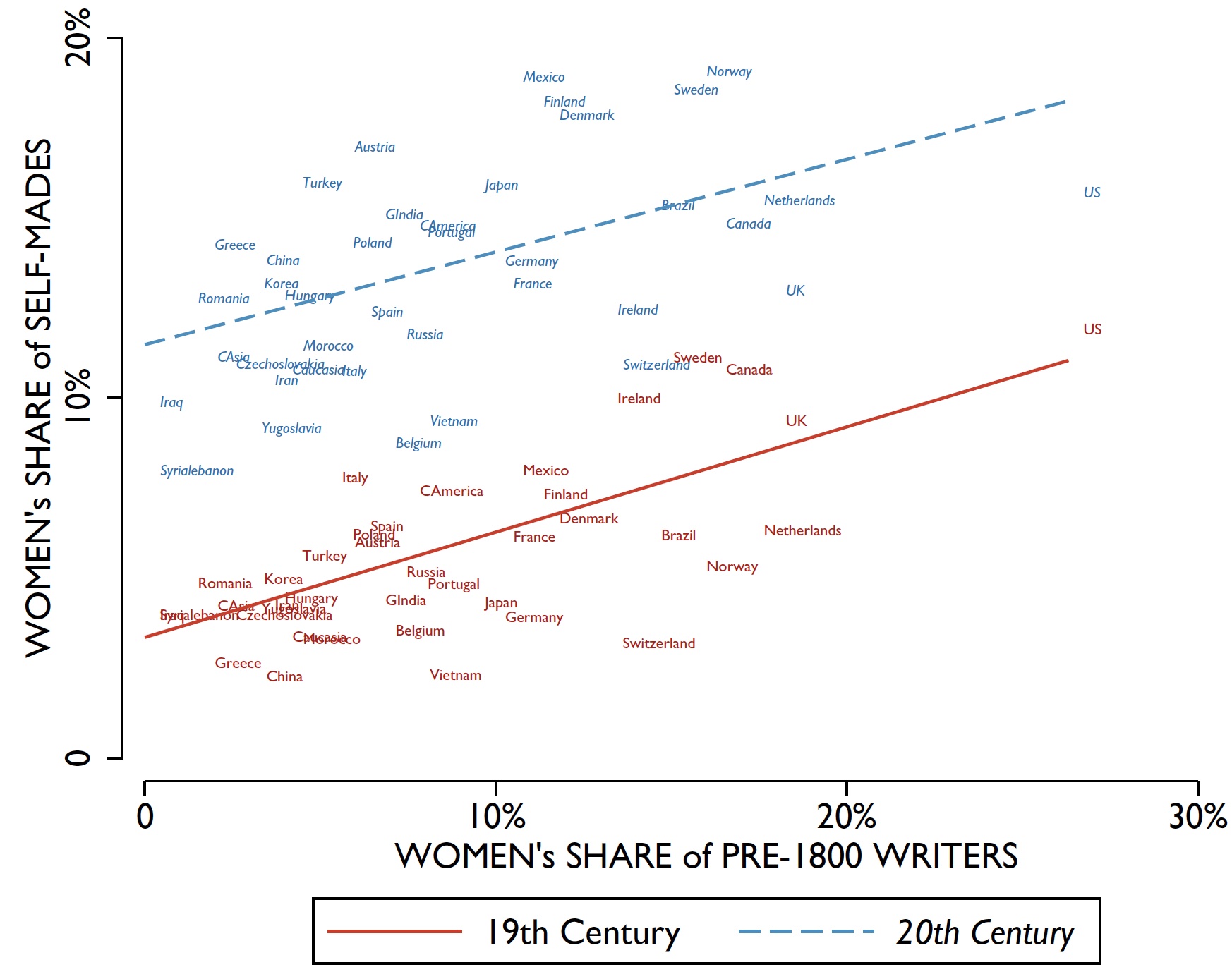

A strong writer wave in the 17th century predicts a more substantial take-off of self-made women in the 19th century (Figure 5). This effect has persisted and created cross-country divergence.

Figure 5 Women’s share of pre-1800 writers vs share of ‘self-mades’

Interpretation

We interpret these historical patterns through the lens of a theoretical framework. Success has different dimensions – pecuniary or not, lasting or not – which all depend on three ingredients related to family connections, control of the individual (skill), and luck. Although all these elements are gender-neutral, their rates of return are not.

The framework illustrates that the return rate of family connections has fluctuated, while a gender gap in the return rate persisted. This led to the trendless movement of the share of women, but no change in self-made women’s share for most of history. The rise of self-made women – both the initial wave in the 17th century among the literary elite and the later broader take-off around the 1800 birth cohort – depicts a rise of return on women’s skill.

We arrived in front of the German school, where my daughter will jump off the bike. Here, Sophia Brenner (1659–1730) was exceptionally allowed to study when the school was only open to boys. In our data, she is part of the literary wave of women writers of the 17th century (Figure 3).

Latin, the language necessary for a professional career, was considered inappropriate for Sophia Brenner. But when the Latin teacher spotted her assisting a fellow with his Latin homework, the teacher asked and received the parents’ permission to teach her Latin too. Her coronation poem to Queen Ulrika Eleonora of Sweden in 1719 justifies her title of ‘the first Swedish spokeswoman for female rights’:

Our body is nothing but the clothes of our soul

the only difference between he and she,

as for the soul concerned, it is just as good,

yes, just as great, in many woman’s body.

See original post for references

Thanks for this, fascinating article. It always annoys me when gender equality is discussed in terms of some sort of dark ages lasting millennia, and then suddenly around the 1960’s everything got better and now we are approaching some sort of nirvana of equality. Even a very superficial overview of history and anthropology shows that relative power between men and women has ebbed and flowed over time, and not just within time, but across and within societies. In traditional European Celtic and Germanic tribes, for example, women could have very high status within certain roles (shamans, warrior queens), even while the general status for the average woman wasn’t necessarily that high. As for early Middle Eastern societies, I believe that archaeologists have noted a degradation in women’s bone structures relative to men as cities grew, indicating that as societies became more stratified, women ending up doing more of the work with less of the status.

Japan I think is a very interesting example of this at work. In Medieval Japan, women had in general what would appear quite a low status, but high status (i.e. rich) women over time dominated literature and many branches of the arts, and economically it would seem that the Ukiyo world of entertainment was a nexus of mostly female economic power. This again, ebbed and flowed over time, with women status seemingly dropping as Japan ‘westernised’ after the 19th Century. In the post war occupation, the US insisted on gender equality, but these often had all sorts of unintended consequences. What has often been portrayed as a victory for women – the claims down on prostitution in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, actually destroyed the economic base of many small female dominated businesses. I always find it amazing how US ‘liberal’ economists like to encourage Japan to be more equal by forcing more women into the workplace where they can work themselves to death, just like their husbands.

I’m old enough to remember in Ireland when a traditional farming family was firmly divided into two – the household, controlled by the woman, with the farm controlled by the wife. As a child I was amazed at how my uncle pretty much had to ask his wife permission to come into the parlour. His money was from the farm, but she had side income – the pigs and chickens. But changes in the 1970’s meant that farms became far more commercially oriented, focusing entirely on dairy and beef. This dramatically raised the income of farming families, but meant that the womans control over the household was weakened and unless her husband was co-operative, many farming wives lost their personal area of control. In that sense, they are more ‘equal’, but in relative terms I really wonder if it was a step forward.

Eric Fromm wrote of a mythical age of female predominance, as have others, but I don’t completely have it.

I can only speak personally for the last fifty years, when with the advent of medical birth control, it was possible, probably with the acknowledgement of the male, to steer clear of pregnancy. Not necessarily an easy proposition, as there is also a female urge, which I did not quite have. I was non binary before it was a thing, and I loved my violin more than his thing, but her thing was ok.

Still, kids are great, and I love them, but I never wanted to have sole responsibility. Besides, the Earth does not need more humans.

Alice, you are right that the Earth does not need more humans. In fact, it needs fewer humans. But I have found this a rather controversial thing to say. I know a number of people who believe this but will not say it in public, as it were, for fear of a ferocious backlash.

The issue is the ethics of how to bring that about: within existing power structures the current disaster of COVID responses appears to be the least bad way. (Any talk of redistribution, class power relations or conception of “public goods” having been rebranded as “totalitarian communism)

This is a manifestation of western capitalism having become a suicide cult in the 70s and taking over politics in the 80s.

Since then population, like all other issues of sustainability, has been clouded by focus group tested antagonistic language to ensure any discussion of demonstrable reality degenerates ASAP into acrimonious moral outrage from polarized moral corrals we’re all herded into.

Sigh.

You are getting ‘pushback’ because a statement like “The Earth does not need more humans” is, in fact, an intensely political statement, on both the personal and the global level. Do you wish to expound, sir, on which of the children in your social circle were irresponsibly brought into this world, and which you think should be culled for the sake of the ‘Earth’? Or perhaps you of course love YOUR children (and those of your friends) but, well, perhaps there could be another famine in Ethiopia, or a war in East Asia, and that would solve ‘the problem’, eh? Can you really not figure out what you sound like, when you so casually drop that one into conversation?

Lurking behind this entire conversation, of course, is the issue that the Earth cannot indefinitely support 8 billion human beings without massive changes in agriculture and a wide-spread acceptance of a lower quality of life for those in the First World. Presuming you are in a first-world country, the logical place these conversations go in a hot minute is to question whether or not it was really globally responsible to spend the last year sitting in front of Netflix ordering absolutely everything needed for life through Amazon Prime for a pandemic with a less than 1% death rate. (I’m aware that’s huge in real numbers; the point still stands.) Or to buy that house in the suburbs, or to eat meat every night for dinner, or, or, or… it gets gnarly pretty quick, especially when you consider that everyone in America who does not voluntarily reduce their consumption is paving the road towards to the impending mass death of the poor. Do you really want to bring this fact up in your casual conversations with your neighbors about the weather?

What’s so utterly frustrating to me about the “Earth should really have less people” crowd is that they DO NOT THINK THROUGH THE IMPLICATIONS OF THEIR OWN STATEMENT. It’s not that it’s “controversial” – it’s that it’s OBVIOUS, and therefore the real question is “What, then, should we do about it?” And the answers are not pretty (they start at “really, we should have let COVID take out as many as possible, it provided a comparatively gentle death” and go from there) and they are not appropriate to casual conversation. Period.

Do not complain about “the backlash” when your chosen conversation topic cannot go anywhere but looming, inevitable mass global death, which the people you are talking to (and you, and I, let’s not be obtuse about this) are personally responsible for precipitating. Just tell them their baby is cute, don’t have children you don’t want, and buy as many locally-made products as you can. It’s the most we can realistically do.

It starts from there? Really? Mightn’t it start from, say, ‘the Catholic church’s position on birth control has been a harmful disgrace and should be reversed’, to take but one example?

The huge problem here is that these *economists* are not cognizant of what economics meant before the time of Adam Smith and the American Revolution and the beginnings of the Industrial (and Financial) Revolution. For in the primarily agricultural world in which humans lived for 4,750 of the past 5,000 years, economics (oikonomía, hence the old spelling œconomics) meant the management of an oikos, i.e. of an agricultural estate: oikonomía = plantation-management, in which the head of this standard *œconomic* unit had absolute legal authority over his wife, his children, and his slaves/serfs/sharecroppers. Feminism is a purely modern societal innovation like investment banking, and largely for the same historical reasons.

Everybody looks the same height on Zoom!

Good point for “The single variable that best explains how much they (females) earn is height.”

Not sure about “they”. The previous sentence is “Harvard Business School tracks lots of data about its graduates.” So do they specifically gender-differentiate the favoritism on height? Or do they just extrapolate mingled statistics where this favoritism/discrimination is pretty prevailent on males?

This factoid was true as of 1979, when I attended HBS and its cumulative women graduates as of then would be <5%, so this does not have to do with gender. First HBS class with women was 1965 and then only 8 out of 800. In fact, the person who recounted the data was a 5'2" man.

I can tell you, as anyone in business can, that very tall men (over 6'3") are advantaged in promotion. Their height enables them to dominate in any interaction.

Thank you for the bit of data. If women numbers were relatively small then, I would be interested in the dynamics of women preferences and experiences (across the height spectrum) additionally.

‘But Michael Hudson has mentioned that women ran (and it sounded as if they were owner/managers) of beerhouses, and they were important back then.’

Yes, this was true but with a proviso and I will quote from an online article on life in ancient Mesopotamia-

‘For the most part, women were relegated to the lower class jobs but, clearly, could hold the same esteemed positions as males. Women were the first brewers and tavern keepers and also the first doctors and dentists in ancient Mesopotamia before those occupations proved lucrative and were taken over by men.’

https://www.ancient.eu/article/680/daily-life-in-ancient-mesopotamia/

You read that and say that oh yeah, this was in olden days. But. It use to be women that did all the computer work in the early years until it was realized that they could be lucrative jobs. So then the women were deliberately pushed out of computing in Silicon valley until the culture of that place became a sort of ‘bro’ town. Same thing happened as thousands of years ago so nothing has really changed. And if a woman’s height is an indicator of her future success, that just points to the immaturity of our culture and its values.

The position of women over the ages is hard to track as it meant different things at different times but you want to know the position of average women and not small elites or just individuals. I was reading how in one region in frontier America, the men were the farmers doing the hard work but when it came time to sell the crops to the agents, it was the women who did all the negotiating. So what was the power relationship here? And how much would it show up in the historical records? As I said, it is hard to track power relationships over the ages.

I remember listening to a story on my public radio station a year or two ago, talking about when women were directors in Hollywood. Then talkies became a source of income, and being a director became a good paying, prestige job, and men took over.

I used to deliver organic food to food co-ops in the 70s. When I delivererd to buying clubs and co-ops, where the labor was exchanged for membership, and unpaid, I was dealing with women. At natural food stores, where I delivered to paid employees, I was dealing with men.

There was an American Experience documentary on Tupperware which talked about its origins and how it became a successful organization as women sold Tupperware to housewives. But when it got to the point that serious finance from local banks were needed to expand, it was the husband of these women that had to go down to the banks with them and pretend that they really ran things as banks were loath to deal with women in business at the time.

Height is a real social psychology observation. Humans are more submissive to larger humans. It is not an issue if maturity.

Thanks for more to think on.

Not really knowing enough to analyse, I was struck by my observation of the Figure 1 active fluctuation beginning with the rise, and through the fall, of the Roman Empire (300BC-500AD) and the emergence of Christianity after the turn of the millenium, compared to before and after.

As ever, I’m intrigued at how the Mediterranean world gets shorted when it doesn’t fit an analysis suitable to givens in the Anglo-American world.

Figure 2 isn’t quite accurate. Just look up the Salerno Medical School and the women faculty there during the middle ages. Trota of Salerno, of the 1100s, is the one with the most reliable records. She wasn’t alone.

University of Bologna has always insisted that women were on the faculty quite early. Here is at least one (Wiki entry): “Bettisia Gozzadini earned a law degree in 1237, being one of the first women in history to obtain a university degree.[22] She taught law from her own home for two years, and in 1239 she taught at the university, becoming the first woman in history to teach at a university.[23]”

Her family may have been “noble,” but so much of the nobility in Italy scraped along that the advantages were sometimes minor. A good example is Sofonisba Anguissola, born in 1532–earlier than the figures here support. She had a brilliant career as a painter. I note her contemporary Lavinia Fontana.

The writer and actress Isabella Andreini, contemporary with Anguissola and Fontana, was one of the most highly regarded artists of her time.

I”m not saying that a revolution was going on in Italy, but I am saying that the biographical database used for the article has some problems. The result is an analysis that is interesting but culturebound.

In Nigeria, in the ’50s, the local markets were almost 100% owned and run by women.

The standard unit of volume measure was a Cigarette can (Tin), and it had to be full up to the pointed top of the pile goods in the can.

At that time the locals would not buy anything in a closed box. Open container, or “no sale.”

“women who became part of the elite were either born into influential families or married into them. We show that women’s power has been a side-effect of nepotism: the more important the family connections, the higher the share of women at the top”

– so it is class, not sex/gender then?

Bicycles may showcase women status or freedom in some countries, but they are certainly not a status symbol for men. Rather, bicycle commuters are often lowly (possibly geeky, or perhaps deplorable, chronically single) males. Consider this link: https://www.quora.com/What-screams-Im-lower-class-in-Japan

“ We measure the female share of people at the top of the social hierarchy in each era as a proxy for women’s status. This measure echoes how we today use the female share in almost all our debates on women’s emancipation.”

I don’t. This sentence gives the game away. The article appears to be an attempt to dress up modern representational femininism in statistical clothing to make it look authoritative. I don’t use the proportion of female presidents or CEOs as a proxy for the ability of my daughters to live full and free lives.

Also, they claim to go back 5,000 years? That dataset would be awfully skewed and limited. They end up with certain biases just be trying to use this data set- cultures that wrote stuff down, cultures that wrote stuff down on rocks (Egyptians), within cultures, what the authors thought were “power” positions. But the article papers over theses issues by calling their work data based.

Matrilineal societies:

https://blogs.dw.com/womentalkonline/index.html%3Fp=11419.html

http://web.pdx.edu/~caskeym/iroquois_web/html/iroquoiswoman.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plains_Indians#Gender_roles