Yves here. It’s intriguing that corporations are making buybacks so as to turbocharge momentum trading, as opposed to blunting supposed or actual faltering prices.

And in the stone ages of my youth, financial economists documented that companies were good at selling shares when prices were sparkling. How times have changed.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

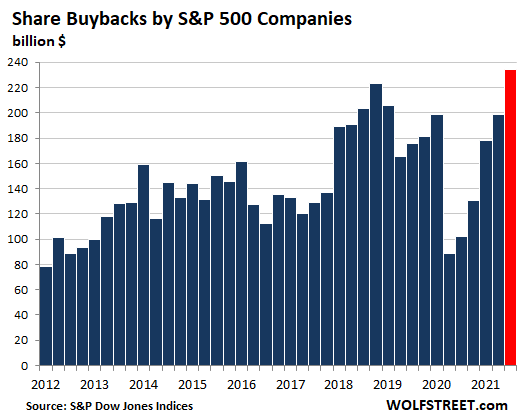

Combined, but heavily concentrated at the top, the companies in the S&P 500 Index bought back a record of $234.5 billion of their own shares in Q3 2021, according to preliminary estimates by S&P Dow Jones Indices, blowing by the previous record of $223 billion in Q4 2018. And there’s more coming, according to Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices, cited by the Wall Street Journal: Buybacks in Q4 would set a new record of $236 billion, he said.

This comes on the heels of a proposed tax of 1% on share buybacks in the “Build Back Better” bill that passed the House on November 19 and is now hung up in the Senate, where the tax hasn’t generated the storm of opposition that other measures in the bill have.

Buy High. Don’t Buy Low.

These buybacks come after share prices have surged in a historic manner, following a historically reckless money-printing binge by the Fed and other central banks, and by historically reckless interest rate repression in face of red-hot and worsening inflation.

But note how buybacks collapsed to $89 billion in Q2 2020 and to $102 billion in Q3 2020, after share prices had plunged. This was based on the corporate strategy of buying high to drive up share prices even further when they’re already high, and not buying when share prices are low.

When prices are high, this is also when insiders are dumping their shares, as they’re now doing, and it’s that much more important for companies to buy back those shares that insiders are dumping.

How Much Difference Would 1% in Taxes Make?

Microsoft announced in September that its board approved another round of $60 billion in share buybacks. A 1% tax on it would cost Microsoft $600 million – not huge for a company the size of Microsoft. But not negligible either.

But if the company can get the buybacks done before the tax becomes effective, if it becomes effective, it would save $600 million while re-absorbing the shares that its executives are dumping hand-over-fist.

And those buybacks work wonderfully when executives themselves are dumping like there’s no tomorrow: For example on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella dumped over 50% of his Microsoft stock in numerous trades in just one day. But the stock barely budged because Microsoft itself was busy buying back shares, and by Friday December 10, shares closed near the pre-dump high.

What does it mean when executives are dumping their shares while the company is buying them back, after a huge parabolic run-up in share prices, fueled by the greatest money-printing binge ever and by interest rate repression, which are now heading into trouble under the withering bout of inflation that those monetary policies have fueled? That was a rhetorical question.

Since the beginning of 2012, the S&P 500 companies have bought back nearly $5.68 trillion of their own shares. A 1% tax would amount to $56.8 billion in additional costs to them.

Over the past four quarters, S&P 500 companies bought back $742 billion of their own shares. A 1% tax would amount to $7.2 billion in additional costs. Not huge. But much of it would be concentrated on the 20 companies that are buying back the largest amount in shares.

New Entries into the Buyback Hall of Fame

Hertz Global Holdings – which emerged from bankruptcy this year and then held an IPO to give the Private Equity firms that had bought it out of bankruptcy a way to unload their stakes – announced in November that it would buy back up $2 billion of its shares, even as the PE firms are unloading their stakes.

This announcement followed other announcements designed to manipulate up its share price so that these stakeholders could make more money when they dump their shares.

The flashiest trick was the announcement on October 25, when Hertz said that it had made a deal with Tesla to buy 100,000 Teslas, that caused its shares to jump over 10%. At the time, I called the announcement a “Propaganda Coup for Hertz’s ‘Selling Shareholders’ & for Tesla.” A week later, Musk tweeted that there was no deal, as “no contract has been signed yet.”

Hertz will do anything to manipulate up its share price to allow the “selling shareholders,” as the group of PE firms are called, to maximize their profits as they’re dumping their shares. And share prices have sagged despite these shenanigans, but would have sagged a lot more without them, from the post-Tesla announcement closing high of $35 a share to $24.92 on Friday.

Another new entry into the mega-share buyback clique is Dell, which announced in September that it would buy back $5 billion of its own shares.

What could possibly go wrong?

The same as last time, perhaps

Do you remember the last time they believed in the markets?

They had been relying on price signals from the markets in the 1920s.

“Everything is getting better and better look at the stock market” the 1920’s believer in free markets

Oh dear.

In the 1930s they discovered that there were two factors at work that had artificially inflated the markets.

1) Share buybacks

2) The use of bank credit for margin lending

They made share buybacks illegal in the 1930s.

What is the fundamental flaw in the free market theory of neoclassical economics?

The University of Chicago worked that out in the 1930s after last time.

Banks can inflate asset prices with the money they create from bank loans.

To get meaningful price signal from the markets you need to ensure bank credit is not used to fund the transfer of existing assets.

Using the money creation of bank credit to fund the transfer of existing assets inflates the price.

This is how the banking system and the markets became closely coupled.

This is why the collapse in asset prices in 1929 devastated the US banking system,

The US stock market is doing really well with share buybacks and margin lending driving prices ever higher.

A former US congressman has been looking at the data.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zu3SgXx3q4

His is a bit worried, hardly surprising really.

“dump” was used eight times in the article. Hmmmm.

When Mr. Market finally takes his dump, after being force fed by the FED, there isn’t a sewer line in existence of sufficient girth to handle the volume and speed of the poop coming down the line.

“Buy back” and it’s variants appear fourteen times. That’s the sound of the rats scurrying out of the sewer lines, seeking higher ground.

Talk about a fatberg!

Even Warren Buffet, who long decried stock buybacks as financial chicanery,

has joined the party:

Buffett’s Berkshire Appetite Surpasses Cash Spent on Apple Stock [Bloomberg]

Musical chairs with other people’s money.

The chart at https://www.yardeni.com/pub/sharesos.pdf indicates that the total number of shares in the S&P 500 companies bottomed-out in the 1st quarter of 2020 and has risen since then at roughly 1%/year. So Wolf’s comment

“the companies in the S&P 500 Index bought back a record of $234.5 billion of their own shares in Q3 2021, according to preliminary estimates by S&P Dow Jones Indices, blowing by the previous record of $223 billion in Q4 2018. And there’s more coming, according to Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices, cited by the Wall Street Journal: Buybacks in Q4 would set a new record of $236 billion, he said.”

doesn’t exactly support the idea that the $235.5 billion shares bought back in Q3 2021 is “blowing by” the previous record of $223 billion set in Q4 2018. There were 1-2% more shares in the S&P 500 and 1.5% more shares brought back. This isn’t exactly an upward trend in stock buybacks compared to the usual fluctuations in buybacks… but the numbers are worth watching.

That said, Yves’ comment about the “Execs Dump/Company Buys Back” cycle is right on the money. It would be interesting to see a stock-buyback chart compared to an executive-dumping chart to see what the longterm corollation is. As for me, I’ve been 100% out of the market since Thanksgiving… and even though the market is up 1% since then I still Give Thanks I’m out every day.

Between buybacks AND passive investing into indexes by the pleebs, the insiders can cash out slowly without raising too much alarm.

Buying into indexes seems like helping many of these same players at the few companies with outrageous valuations sell high. Indexers are most often long term (bag?) holders

There’s going to more individual investors holing the bag pretty soon.

As a financially naive person, I’m wondering: why this isn’t considered blatant stock manipulation for personal gain by corporate officers, and so illegal?

Up until 1982 share buybacks were illegal and considered to be stock price manipulation.

So it falls to the directors to manage a conflict of interest? Hah!

Yes, this is entirely the SEC’s fault. Rule 10b-18.

Transparent enriching of a the largest shareholders. In what universe is it not a massive conflict of interest to have the CEO dumping shares while the company is buying at all time high prices? We really have learned nothing and will continue to allow short term thinking executives to fatten their pockets while underinvesting in their firms line of business.

Every time I look at those charts, I double check to make sure my bank accounts are under FDIC limit, because in the end, when the music stops, I think the banks will be holding the bag like last time.

Will they be bailed out this time again, that is the question.

Build Back Better may not be gaining much traction, but Buy Back Better certainly has.

Underappreciated comment!

Don’t put too much faith in the FDIC. Derivatives are legally classified as super senior debt and can vacuum up any assets in a bankruptcy (including FDIC funds)

Now you scare me.

Do you mean that FDIC is worthless if your bank goes under?

Please provide source of your info.

Where is Buffet holding his 150 billions in cash?

Maybe I missed it–but is there some measure of overall buybacks? This post seemed to focus on anecdotal examples for a couple of companies. Is that representative?

So many ill winds in crescendo, in seeming concert, bode an unholy climax.