Yves here. More collateral damage from the Ukraine conflict, this time China’s lending to emerging economies. The US has been threatening secondary sanctions. Worse, one has to wonder if the postponed Pelosi trip to Taiwan is saber-rattling that the US might recognize Taiwan. China would almost certainly retaliate, the question is how.

By Sebastian Horn, Economist, Office of the World Bank Chief Economist; Carmen Reinhart; Minos A. Zombanakis Professor of the International Financial System, Harvard Kennedy School; and Christoph Trebesch, Professor of Economics, Kiel Institute for the World Economy; CEPR Research Affiliate. Originally published at VoxEU

China and Russia have built close financial ties over the past ten years, with Russia becoming the largest recipient of Belt and Road lending. Given the sums at stake, the war in Ukraine is putting China’s overseas lending portfolio at higher risk than ever before. This column argues that this is likely to make Chinese state-owned banks more cautious in extending fresh international loans and in rolling over old ones. Because China is a common lender to many developing countries, they now face the added risk of a ‘sudden stop’ in foreign lending.

Editors’ note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war.

Russia’s attack of Ukraine is causing staggering human suffering and destruction. The impacts on global commodity markets are being acutely felt, as oil and wheat prices have soared, and volatility has increased markedly (e.g. Balma et al. 2022). The broader economic implications are only beginning to be understood (e.g. Danielsson et al. 2022, Bachmann et al. 2022, Korn and Stemmler 2022).

Looking ahead, a central question is the role of China and the Chinese–Russian relationship. So far, the public debate has mainly focused on China’s potential support for Russia as well as the long-term effects for trade between the two countries (e.g. Palmer 2022). What is less understood is just how financially interconnected the two countries already are.2 Russia is the largest foreign debtor to Chinese state-owned banks, accounting for more than 15% of Belt and Road lending between 2013 and 2017 (Custer et al. 2021). This column summarises the debtor-creditor relationship between Russia and China and discusses potential spillover effects to the rest of the world, particularly emerging markets and developing countries (EMDEs).

China’s Overseas Lending Portfolio and the Role of Russia

China’s state-owned banks and enterprises have invested in and lent heavily to Russia, the Ukraine, and Belarus. Cumulative Chinese lending to Russia since 2000 exceeds $125 billion and has mostly financed Russian state-owned enterprises in the energy sector. Total Chinese lending commitments to Ukraine are estimated at $7 billion and have largely supported projects in agriculture and infrastructure. In addition, Chinese banks also have considerable exposure towards Belarus, with around $8 billion in cumulative lending since 2000. Taken together, the three countries account for close to 20% of China’s overseas lending during the past two decades.

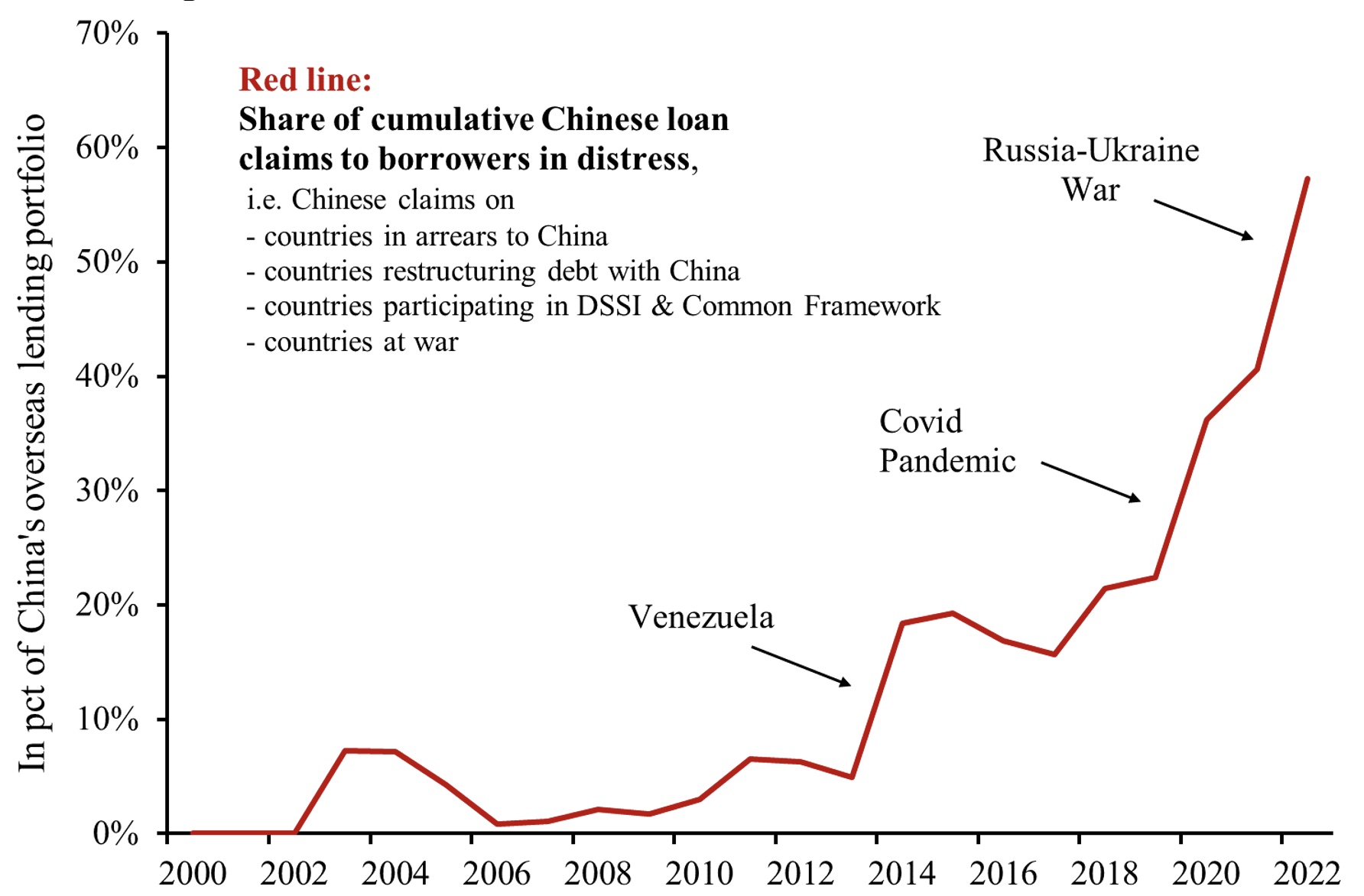

For China, the war implies yet another increase in the exposure of its overseas loan portfolio towards debtor countries at risk of default. China’s exposure towards distressed debtors had started its upward march as early as the mid-2010s, when Venezuela defaulted on its debts. Default risks intensified and spread geographically with the pandemic, when more and more developing economies entered distress; almost 60% of low-income countries are now in debt distress or at high risk.2 As a result, China’s state banks now hold a large amount of potentially ‘distressed’ debt. Figure 1 shows the share of China’s total credit portfolio to borrowing countries in distress, which has increased from about 5% in 2010 to 60% at present. The figure traces the share of cumulative overseas lending that has been extended to countries currently in debt distress or involved in a war.

Figure 1 Share of Chinese loan claims to borrowers in distress

Note: This figure shows the share of cumulative Chinese lending to developing countries that are in distress. The line counts all recipient countries that are in arrears to China, that have restructured debt with China (bilateral or under the DSSI) or that are at war. Data is from Horn et al. (2021, 2022), Custer et al. (202) and the World Bank International Debt Statistics.

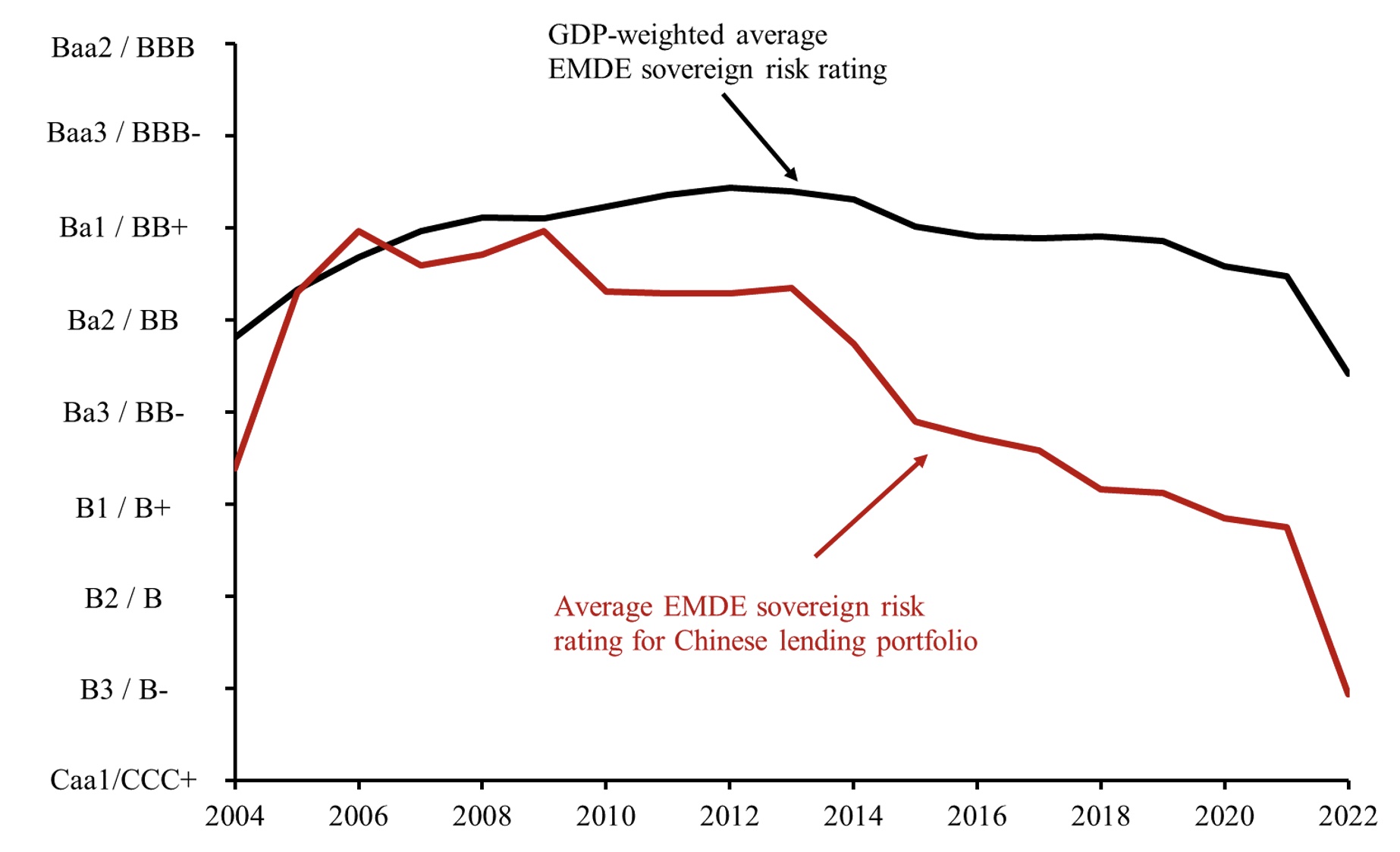

Figure 2, which takes a different angle focusing on sovereign risk ratings, arrives at a similar conclusion. The average credit quality of China’s lending portfolio has deteriorated considerably in the past ten years. On average, recipients of Chinese loans were downgraded by five rating brackets, compared to an average downgrade of two brackets in a GDP-weighted benchmark portfolio of EMDE debt.

Figure 2 Sovereign credit risk in EMDEs: China’s lending portfolio versus benchmark

Note: This figure shows the average sovereign credit risk ratings for 108 developing and emerging market countries, for which data is available. The credit risk rating is an average across ratings by Moody’s, Fitch and S&P. The black line shows a GDP-weighted average (with GDP measured on a PPP basis), while the red line shows the average rating of China’s overseas lending portfolio, which was obtained by weighing ratings with cumulative lending commitments. Data is from Horn et al. (2021), Custer et al. (2021), Reinhart et al. (2017) and the World Bank World Development Indicators.

Distressed Chinese Loans and the ‘Hidden Defaults’

China’s overseas lending and credit relationships remain exceptionally opaque. Chinese lenders require strict confidentiality from their debtors and do not release a granular breakdown of their lending (Horn et al. 2021, World Bank 2021). Moreover, Chinese official loans and related credit events are not on the radar screen of major international credit rating agencies and no systematic data on related defaults are collected by international organisations such as the OECD, the IMF, or the Paris Club. Most Chinese debt-restructuring deals are arranged bilaterally and with little or no publicly available information. As a result, there is a substantial knowledge gap on what happens to Chinese claims in situations of debt distress and default.

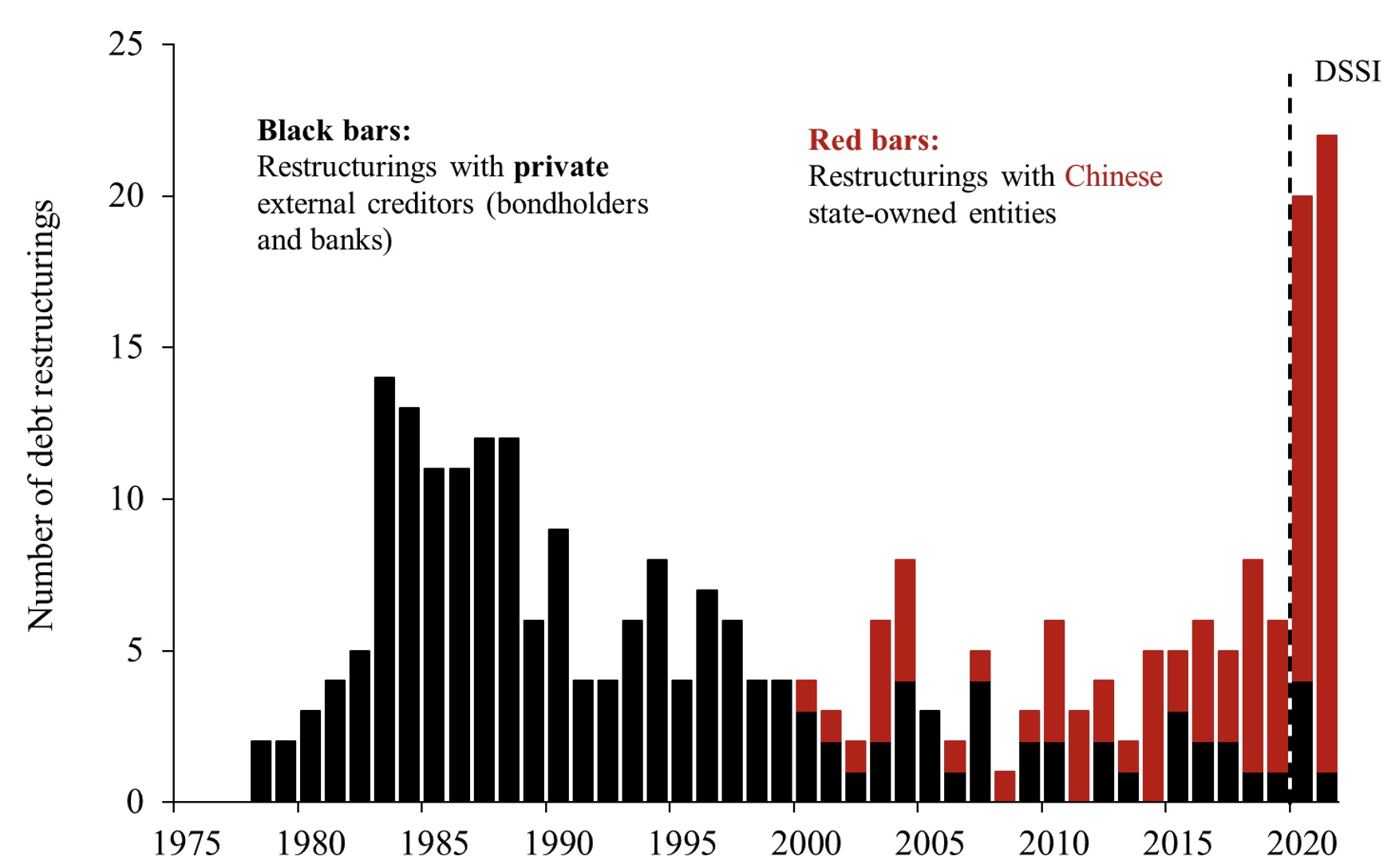

In a new paper (Horn et al. 2022), we help to fill this knowledge gap by assembling an encompassing dataset of sovereign debt restructurings with Chinese lenders from a variety of sources. Since 2008, Chinese creditors arranged at least 71 distressed debt restructurings – more than three times the number of sovereign restructurings with private creditors (we record 21 bond and bank debt restructurings) and higher than the total number of Paris Club restructurings with distressed debtors (68 cases) during the same period. As our earlier work documents, China has become the most important official player in international sovereign debt renegotiations. Moreover, Chinese lenders follow a crisis resolution approach reminiscent to Western lenders in the 1980s and 1990s. Except for symbolic, debt cancelations of small zero-interest loans, Chinese lenders almost never provide deep debt relief with face value reduction. Like their predecessors, they arrange reschedulings that offer some grace period, or short-term cash flow relief. Nominal debt write-downs are extremely rare as are reductions in the interest rates charged. The result is often serial debt restructurings. It remains to be seen whether Russia’s substantive debts to China will follow this set pattern, as has been the case for other oil producers (Angola, Ecuador, and Venezuela, among others).

Figure 3 Hidden defaults: Restructurings with China and with private external creditors

Source: Horn et al. (2022).

Note: This figure combines data on distressed debt restructurings on private external creditors (bondholders and banks) from Asonuma and Trebesch (2016) with those on Chinese creditors from Horn et al. (2022). The Chinese cases include 33 debt reschedulings with countries in high risk of or at debt distress in the wake of the DSSI over 2020-21. To avoid bias, 149 “symbolic” restructurings of minor, zero-interest loans are excluded.

Against this backdrop, it is no surprise that comparatively little is known about the financial link between China and Russia (or China and other countries, for that matter). Data on defaults and arrears are not publicly available. In fact, since 2008, the only ‘truly’ reliable data on sovereign defaults are for sovereign bonds, which are tracked meticulously by rating agencies and the global press.

Collateral and In-Kind Repayments

We do know that China’s state banks use innovative contractual designs with elaborate safeguards against financial and political risk. In this sense, they are better poised to deal with the financial fallout they are now facing. Gelpern et al. (2021) show that a significant share of China’s lending is collateralised, especially to commodity exporting countries. This implies that Chinese lending to distressed countries is not necessarily in default or non-performing but might be serviced through the proceeds of commodity exports. Russia is a case in point: an important share of Chinese lending took the form of advance payments for oil deliveries. Under a 2013 agreement, the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNCP) made advance payments of at least $30 billion to Rosneft in exchange for long-term oil deliveries through the Russia China oil pipeline. It is highly probable that Russia may continue to service the loans in kind, even if it were to default on other creditors (as was the case with Venezuela) and despite the sanctions imposed by Western governments.

Global Implications: Roadblocks in the Belt and Road?

What are the broader global implications of these developments? Kaminsky and Reinhart (2000) stressed that cross-border financial contagion often arises in the context a ‘common creditor’ (in this case China). When a portion of the loan portfolio becomes impaired, the common lender rebalances risks by lending less to other potentially risky borrowers. The result is less or no new lending and a reduced appetite for rolling over pre-existing debts of other (sovereign) borrowers. This web of cross-border lending sets the stage for a sudden stop – including to borrowers that have no other bilateral trade or finance connections with the borrower(s) in distress (see also Kaminsky et al. 2003, Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2013, Morelli et al. 2022).

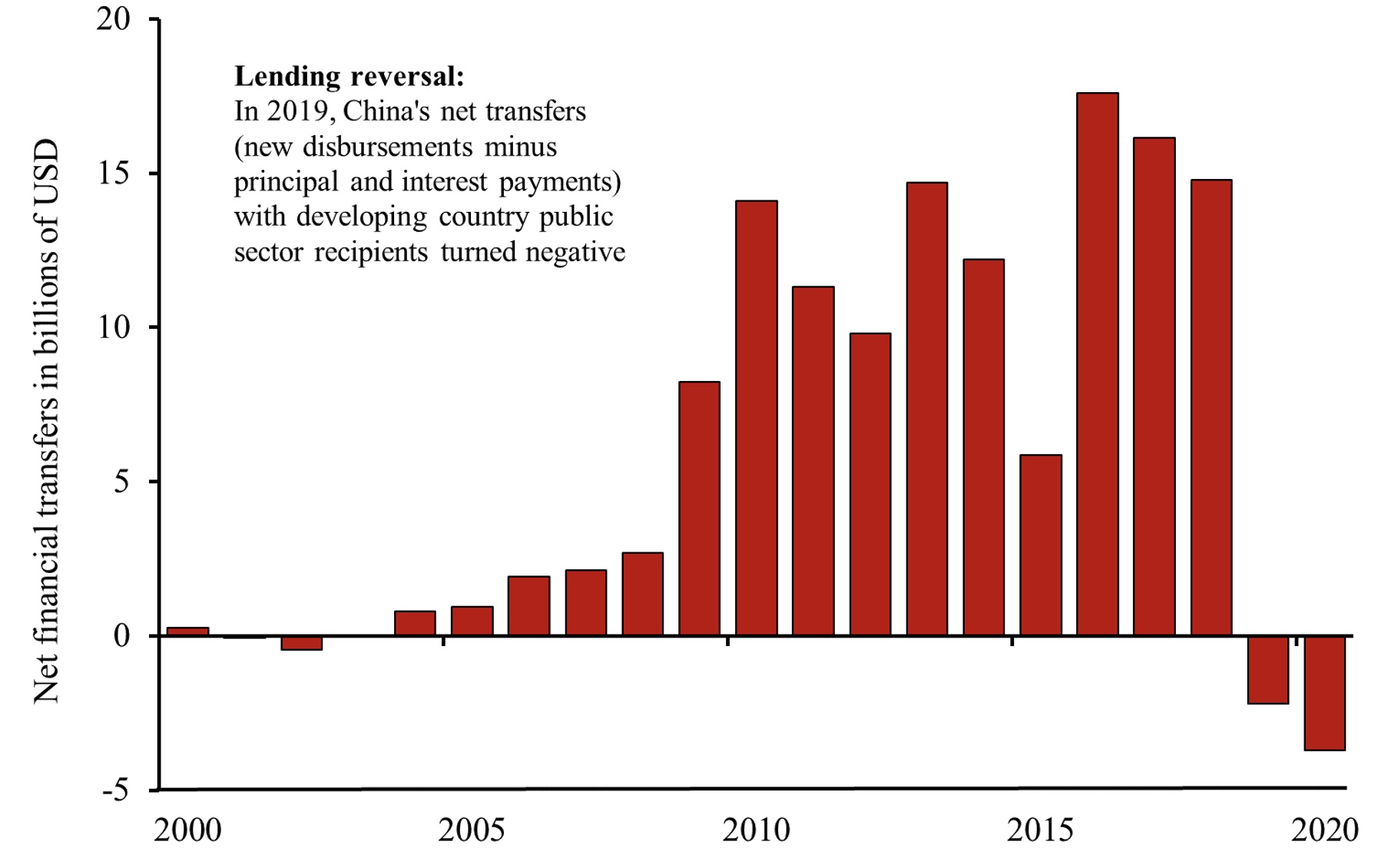

The available evidence suggests that China’s multi-year overseas lending boom had already largely ended and is hitting fresh roadblocks with the Russia-Ukraine war. This is especially bad news for EMDEs, at a time when global financial conditions are poised to tighten as major central banks attempt to rein in rapidly rising inflation. Such a sudden stop impacts much of the developing world who owe large amounts of debt to China. Net transfers from Chinese bilateral creditors to developing country public sector recipients have turned negative in 2019 and 2020 after peaking in 2016 (Figure 4). This means that principal and interest repayments to China now exceed fresh disbursements.3 Chinese policy banks have turned from a source of developing country growth (Müller 2021) into net ‘global debt collectors’. The Russia risks could amplify that trend.

Figure 4 Sudden stop? Chinese net financial transfers to developing countries

Note: This figure shows net transfers (new disbursements minus principal and interest payments) from Chinese bilateral creditors to public sector recipients in developing and emerging market countries. Data is from the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics.

The Global South faces new risks of a ‘sudden stop’ in Chinese lending and ripple effects may be substantial. As Chinese banks face pressure both at home (Rogoff 2021) and abroad, their appetite to provide fresh financing and meaningful debt relief to developing countries is poised to decrease. Moreover, it may become more challenging to refinance existing debts that are coming due.4 Chinese loans have comparatively short maturities (Horn et al. 2021) and need to be rolled over frequently. For many poor and highly indebted countries this implies a growing dependence on Chinese debt ‘evergreening’, because alternative sources of (re-)financing may be unavailable or prohibitive in cost.

In sum, the Russia-Ukraine war is likely to have significant financial implications not just for China and the countries in Central Asia that are closely linked with Russia, but also for capital flows and debt restructurings in dozens of developing countries spanning nearly all regions. Many of these same countries will also be impacted by the rising cost of food and energy, yet another by-product of the war.

Authors’ note: The authors would like to thank Manuela Ferro and Martin Raiser for helpful comments and suggestions.

See original post for references

I think the evidence is that China has been retreating from foreign investing for a few years. After an initial bout of enthusiasm, a lot of bank lenders got badly burnt when they discovered that its easier to lend in places like South America than to get the money back. For a brief period, the Chinese took the place of the Germans as everyones main source of stupid money.

Is this what they used to call “tribute”?

The USA! USA! USA!, via the World Bank & IMF, is in the same boat. But in contrast to China, there is the constant threat hanging over the heads of the countries that got dough from those organizations of “nice country you got there, it’d be a shame if it got Freedom Bombed”

There seems to be a complex mixture of effects due to Chinese banking. We hear that oil refiners in china are using cash transfers (telegraphic transfers) instead of using bank letters of credit although more recently smaller local banks present in Russia are stepping in. We do know the ICBC Chinese bank is not issuing dollar denominated letters of credit but will in Yuan. It is suggested that this is related to sanctions and dollar clearing with Chinese state banks taking control of banking in Russia. Similar issues are happening for copper and other commodity exports from Russia. This is the official story but perhaps Professor Hu Wei recent essay hints at other things going on behind the scenes.

https://www.thearticle.com/china-russia-and-risk

The article details a pull back from overseas lending by China but it looks like Chinese state owned Insurers exposure as well as Chinese banking might be a driving factor. These insurers own billions of dollars of assets some of which may be Russian and subject to becoming state owned. This looks like Chinese business no longer trust deals made with some Russian parties and this mistrust may spill over to other countries.

https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/banking-finance/china-asks-state-insurers-to-review-exposure-to-russia-ukraine

I still feel their are pieces of this financing puzzle missing and it could spill over into political arenas. Yet again the worlds poor are likely to get stuck in the crossfire.

Horn, et al — “Gelpern et al. (2021) show that a significant share of China’s lending is collateralised, especially to commodity exporting countries. This implies that Chinese lending to distressed countries is not necessarily in default or non-performing but might be serviced through the proceeds of commodity exports. Russia is a case in point: an important share of Chinese lending took the form of advance payments for oil deliveries.”

Let’s begin with a map — I like this one Eurasian Economic Union

Re-examine China’s overseas lending from the perspective of its national security strategy, especially with the addition of food security last November.

In which case, defaults and non-performance are conceptually charged against the national security budget.

Re-examine China’s overseas lending from the perspective of overseas influence/power projection, not just with its huge commercial fleets but also with its three prong national security fleet: hundreds of thousands of fishing ships; the world’s largest coast guard; and the world’s second largest navy. And it has developed, trained and demonstrated global integrated coercive grayzone fishery operations with that fleet.

In which case, defaults and non-performance are conceptually charged against the national security budget.

My assertion is China’s overseas lending difficulties are manageable, not debilitating, from the perspective of national security especially its aggressive actions to ensure food security for its 1.4B citizens.

And if (when) the independent international monetary and financial system described at Sausage Factory March 27, 2022 at 5:44 am comes into existence, I’m sure China’s money magicians will fix its overseas lending accounts.

Is ” global integrated coercive grayzone fishery operations ” a nicer way of saying fish-piracy and aggressionist fish strip-mining in non-Chinese waters? Including in the Illegally Occupied West Bank of the China Sea?

Yep. Back in 2010 when the U.S. takes a tougher tone with China there was this confrontation:

Relations have pretty much gone downhill from there. It takes a hard man to feed 1.4B people.

I know nothing about finance let alone international finance but if I understand it, the authors are saying, ” China is incredibly secretive about its international financial affairs and we have almost no data on what they are doing or why they are doing it but here is our best guess based on wild surmise and a bit of wistful thinking?

I may be a bit too harsh as I clearly do not understand their arguments but I think I’ll go back to the Ouija Board.

BTW I find the @RobertC April 9, 2022 at 12:56 pm argument very interesting. Horn, Reinhart, & Trebesch may be making cultural and economic assumptions that make no sense in the Chinese context.

Why is there so much international lending?

No one knows you can create all the money you need internally.

It was only after a thorough investigation into 2008 that I realised I didn’t know what real wealth creation was.

I had been confused about money and wealth.

Financial crises are the keys to unlock the secrets of the monetary system.

The Japanese financial crisis in 1991 was a very significant key.

Richard Werner and Richard Koo turned the key.

They both opened different doors into understanding what had happened.

Richard Werner looked into what had happened to cause the financial crisis.

Richard Koo looked into what had happened after the financial crisis.

It was Richard Werner that proved banks create money, and this got central banks to reveal the truth starting in 2014.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

By the time I started in 2008 a lot of the doors were already open, and I could go on to open a few more.

No one else seems to have followed this path, but it seemed like the next logical step to me.

If banks create money out of nothing, which they do.

What is real wealth?

This was a hard one, and I was lucky they had been through it before in the 1930s.

GDP measures economic activity in the economy; the new items produced and sold every year in the economy.

This is where the real wealth in the economy lies.

Neoclassical economists have always excelled in creating wealth of the evaporating kind.

Inflated asset prices.

What is the relationship between money and wealth?

It is easier to see when it all goes wrong.

Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe were never short of money.

Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe had created far too much money compared to the goods and services available within the economy causing hyper-inflation.

States can just create money, and the last thing you want is too much of the damn stuff in your economy.

They had made so much money it lost nearly all its value, and they needed wheelbarrows of the stuff to buy anything.

Money has no intrinsic value; it comes from what it can buy.

Central bankers actually look at the money supply, and expect it to rise in line with the new goods and services in the economy, as it grows. More goods and services in the economy require more money in the economy.

Paul Ryan was a typically confused neoliberal and Alan Greenspan had to put him straight.

Paul Ryan was worried about how the Government would pay for pensions.

Alan Greenspan told Paul Ryan the Government can create all the money it wants, there is no need to save for pensions.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNCZHAQnfGU

What matters is whether the goods and services are there for them to buy with that money.

That’s where the real wealth in the economy lies and it’s measured by GDP.

Money is just an instrument to facilitate transactions in the economy, it comes out of nothing.

It you create too much of it, it becomes worth nothing.

The secret is to ensure the money supply grows with GDP.

Government can create money, and as long as they don’t create too much of it there won’t be a problem.

Private banks create money, and you should ensure GDP grows with the money they create.

Banks – What is the idea?

The idea is that banks lend into business and industry to increase the productive capacity of the economy.

Business and industry don’t have to wait until they have the money to expand. They can borrow the money and use it to expand today, and then pay that money back in the future.

The economy can then grow more rapidly than it would without banks.

Debt grows with GDP and there are no problems

The banks create money and use it to create real wealth

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

When you have a firm grip on what money and wealth really are; and know how banks work, it all falls into place.

The money to invest in business and industry should be created out of nothing by private banks.

This is how the monetary system should work.

The lead paragraph in the VOX debate states: “Russia’s attack of Ukraine is causing staggering human suffering and destruction. The impacts on global commodity markets are being acutely felt, as oil and wheat prices have soared, and volatility has increased markedly (e.g. Balma et al. 2022).”

The “staggering human suffering and destruction” is not true, although the suffering is very real. What the USSR and US did in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria make the Ukraine disaster look minor league. But the Ukraine is on TV and the front pages of the NYT and WP. So the lesson is: “Even seemingly sophisticated viewers are eventually influenced by comprehensive propaganda campaigns.”

But the “impact on global commodity markets” is real. So let’s be honest: destroying a country off-TV is OK; destroying a country on TV isn’t; annoying your voters with cost-of-living increases is worse than either.

On Chinese lending. Geopolitical lending leads to lending risk; it is cosigning your deadbeat brother-in-laws car loan to keep your nagging sister happy. When the US was rich, we did this through the World Bank and the IMF. IMF and World Bank loans didn’t default, they are “restructured” and the ensuing reduction in the available capital to loan was covered by a “new round of capital injection.”

During the Cold War the lenders were the US and the USSR. Now China is the lender. Political loans often suffer invisible default- Cuba, Nepal, most of Black Africa… the economies didn’t reap the benefit from the loans and thus there was no increased production to pay-off the loans.

The neat chart showing “Chinese loans to borrowers in distress” assumes “Russia is in distress” and “in distress” = “likely to default”. Since the Russian Ruble is now back up to where it was before the Ukrainian invasion, and the shipment of Russian raw materials to China continues, there is no reason to believe that the borrower is “in distress”. These Chinese geopolitics loans to Russia might be considered Chinese victories just as American geopolitics loans to Greece and Turkey were a US victory- they tied the target country into the economic sphere of the lender.

All that said, the “Sudden stop” problem is real. But the Chinese trade balance must be recycled somewhere. Given the new American “We will take your gold and not let you use your dollars” approach, the only question is: “How will China prefer to recycle the trade balance? Through the US, by lending to weak debtors, or by stockpiling natural resources from weak debtors?” The latter would be one way of preparing for any aftershock from a Taiwan showdown.