Yves here. Poskett takes issue with the Euro-centric story of science and discovery.

By Dan Falk (@danfalk), a science journalist based in Toronto. His books include “The Science of Shakespeare” and “In Search of Time.”. Originally published at Undark

Think of a famous scientist from the past. What name did you come up with? Very likely, someone from Europe or the United States. That’s hardly surprising, because science is often taught in Western classrooms as though it’s a European-American endeavor.

James Poskett, a historian of science at the University of Warwick in England, believes this myth is not only misleading but dangerous — and it’s something he sets out to correct in his recent book, “Horizons: A Global History of Science.” Billed as “a major retelling of the history of science,” the book frames the last five centuries of the scientific enterprise as a truly globe-spanning project.

In a recent Zoom conversation, Poskett explained why he believes this retelling is needed. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

“Horizons: A Global History of Science,” by James Poskett (Penguin Books, 464 Pages).

Visual: Penguin Books

Undark: You point out that the history of science, as it’s usually taught, focuses on figures like Galileo, Newton, Darwin, and Einstein. And I think we can agree that those people did actually make vital contributions. But what’s left out when we focus on those figures?

James Poskett: I agree, it’s really important to emphasize that those figures did make contributions that were significant. So my book isn’t about Newton and Darwin and Einstein not mattering. As you say, those people feature in the book. They’re all significant figures in their own right. But by focusing exclusively on them, we miss two global stories.

The first global story is that these famous figures we’ve heard of in fact relied on their global connections to do much of the work that they’re famous for. Newton is a good example, in terms of him relying on information he was collecting from around the world, often from East India Company officers in Asia, or astronomers on slave-trading ships in the Atlantic. So we miss the global dimension of these famous scientists — not just collecting information, but often actually relying on the culture and knowledge of other peoples too.

The other part is the people from outside of Europe who made their own really significant contributions in their own right. There were Chinese, Japanese, Indian, African astronomers, mathematicians, later evolutionary thinkers, geneticists, chemists, who made genuine important contributions to the development of modern science. It completely skews the story if we have this exclusive focus on White European pioneers.

UD: Another interesting point you make is that when textbooks or popular histories of science do mention the contributions of, say, Islamic science or Chinese science, it’s often framed as a historical episode. The reader gets the impression that this was something that happened in the past. In your book, you say this is not only misleading but it can have harmful consequences. How so?

JP: We’re quite actually familiar with the idea that civilizations in the Middle East and Asia, the Islamic world, Hindu civilizations, Chinese civilization — that these contributed in some way to science. But it’s always told as part of a narrative of an ancient or medieval golden age. And I always tell my students, you should be super suspicious, as soon as you hear the term “golden age,” because it’s massively loaded: It’s telling you that there was once this great achievement, there was this once-great civilization — but the emphasis is on “once,” because the “golden age” bit implies a fall from grace, or a dark age afterwards.

At face value, it sounds good — you know, Islamic mathematicians, chemists, astronomers made important contributions in the 10th century — but actually, that’s kind of pushing those achievements way back in the past. It has the rhetorical effect of saying that Islamic science isn’t modern, or Chinese science, or Hindu science, or Mesoamerican science are not part of modernity; there’s something kind of anti-modern about it

Of course, the Islamic world made important contributions to science in the medieval period. But it didn’t suddenly stop. It continued throughout the 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. And that’s really the message of the book.

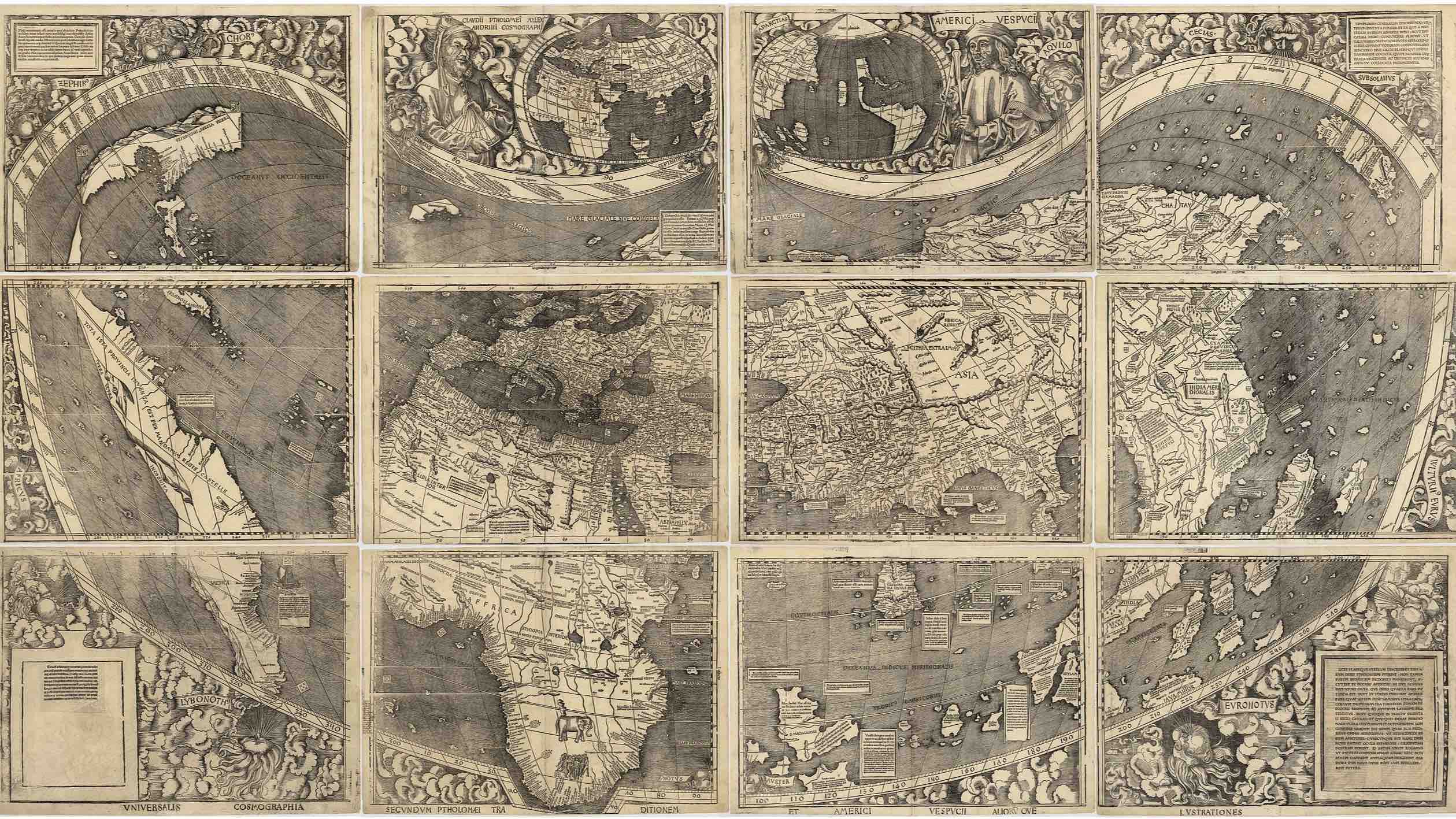

UD: An obvious turning point, not just in the history of science, but in human history writ large, is when Europeans first made contact with the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. In your book, you say that these encounters were critical in terms of thinking of human beings as part of nature. You even write, “The discovery of the New World was also the discovery of humankind.” What do you mean by that?

JP: Broadly, for Europeans, the discovery that there was a “new world” was a major shock to the very foundations of how they thought about knowledge. Knowledge was supposed to be based on ancient texts; it was supposed to be on the authority of ancient Greek and Roman authors, people like Aristotle, or Pliny for geography. And also the Bible was kind of wrapped up with that as well, as a source of ancient authority.

But of course, none of these ancient authors mentioned this enormous continent. And not only was this continent full of life, full of animals and vegetables and plants and minerals that in some cases had not been seen before and weren’t mentioned in the ancient texts — it was full of people!

So this then made thinkers in Europe start saying, well, maybe actually, knowledge isn’t best derived from ancient texts exclusively; maybe we need to go out into the world and look at things to make discoveries. And of course, that’s the metaphor we still use. We talk about scientific “discoveries.”

Humans were seen as separate from the natural world. They were created — in Christian Europe, and most of the major religions at that time — they’re created separately. Humans have a moral element that can be analyzed philosophically and morally, but they’re not meaningfully part of nature in the same way a horse is. But this idea of discovering nature also opened the opportunity that there were things that were to be discovered, not just about the outside world, but about the kind of internal world of the human – that if you could discover a tomato by looking out into the world, maybe you could discover something about humans by looking inside them.

UD: You point out that when we think of the structure of the atom, we tend to think of the New Zealand-born British scientist Ernest Rutherford, who’s often credited with figuring it out. In the book, you talk about an often overlooked figure, Hantaro Nagaoka. Who was he? What was his contribution?

JP: Hantaro Nagaoka was a Japanese physicist. He was born in the mid-19th century. He came from a Samurai family, like many 19th century Japanese scientists, and he was studying physics at a time that Japan was industrializing; where the Samurai were finding a new place for themselves in this modern industrial society. And in the very early 20th century, in 1904, he gave an account of the structure of the atom. He called it the “Saturnian” atom.

He’d worked this out theoretically, rather than by doing experiments. He worked out that, based on complex theoretical assumptions and following these through, that there must be a large, central, positively charged nucleus, surrounded by orbiting electrons. And he called it the Saturnian atom after the planet Saturn, with a big central thing with its rings around it. This is the basic structure of the atom that Rutherford later was famous for developing, for doing the experimental work for — but Rutherford published his paper seven years later, in 1911.

And in fact Rutherford would have acknowledged this. Rutherford cites Nagaoka’s paper at the end of his famous 1911 paper. And Rutherford actually corresponded with Nagaoka. Nagaoka wasn’t some unknown scientist nobody had ever heard of. He was attending conferences in Paris; he came to Britain and actually had a tour of Rutherford’s laboratory in Manchester, where Rutherford did the experiments. And actually, if you look at textbooks from the early 20th century, they mention Nagaoka — he’s kind of just fallen out of the history later on.

So he made this really serious contribution to atomic physics. But he’s one of the smoking gun examples of someone who really came up with a key theoretical piece of science, that was a major influence in the 20th century, but is almost completely forgotten outside of Japan.

My point isn’t that Rutherford stole the idea. My point is that science is made through these processes of global cultural exchange, through these different people making different contributions.

UD: Turning to the present day: You describe the current relationship between the U.S. and China as being like a new Cold War. How does science fit in to this new “war”?

JP: Science fits into it in some ways like the original Cold War, in that science has a practical function. And that’s clearly how states like China, like the United States, like India, the United Arab Emirates —they see it as part of their economic strategy. Basically, that investment in sciences like artificial intelligence will allow a transformation of the economy, increased production — and this is really important for keeping citizens happy, and ultimately having the kind of economic clout to dominate the world economically and politically and through soft power.

Also, in more practical terms, space science has a really clear military element with respect to satellites, rocketry. I talk a lot about climate science being a science that fits with the new Cold War, in that it’s seen by states as a kind of security problem. For China, climate science is important to invest in because their coastal regions are major economic centers. They don’t want those going underwater.

So there are practical elements — but it’s also ideological. We’re seeing a return of a kind of nationalism — this weird combination of globalization and nationalism. Xi Jinping is a nationalist, much more so than some of the previous Chinese leaders. He’s just the most prominent example, and probably the person that’s most likely be able to to walk the walk as well as talk the talk. But nationalist leaders in India, in Turkey, in the UAE, in America, in Britain. Boris Johnson talked about making Britain a new “scientific superpower.” So science also becomes an ideological marker of national prestige.

UD: Throughout the book you sort of argue that it’s wrong to frame the history of science as a European endeavor or an Anglo-American endeavor. Why do you feel it’s so important to rewrite or update that framing?

JP: For overlapping reasons. A basic one is about representation and diversity in science; equity. Science, in Europe and Britain, certainly in America — United States and North America generally — is not equitable, particularly in terms of diversity with respect to minority ethnic groups, but other kinds of diversity as well, in terms of class and gender, disability, and the like.

So I think if the scientific profession is disproportionately people like me — White men who went to Cambridge — then part, but not the exclusive reason for that, is because we repeatedly present to the public, to school children, to university students, an image of the sciences which looks like me. It’s people like Newton or Einstein or Darwin — they’re these White men. And again, my point isn’t that they’re not part of the story. Absolutely they are. But that there are other people from around the world, from different cultural backgrounds, who are part of it.

We’re at a kind of crossroads in history, but also in science. And the narratives that scientists were taught and told themselves in the West was a narrative that was built for the Cold War. But the Cold War’s over — the original one. Yet we’re still telling these narratives about Western science, science being neutral. And I think a lot of public mistrust in the sciences generally is actually a function of this — that we need to present publicly a more realistic, political, diverse account of how science is done – how we got to now — in order to have the consent and engagement of the mass public in the sciences.

I really think that this kind of history of science shouldn’t be seen as a threat to scientists. I’m not doing it because I want to see the end of science, and for all of us become vaccine deniers. I’m doing it for the opposite reason: I think if you want to stem the tide of vaccine and climate denial, and xenophobic nationalism, then you need a history of science which really engages with these quite difficult histories.

The perfect marriage of science and wokeness, sure to generate numerous speaking engagements and future book deals.

The sad thing is that there is, somewhere, a beautiful message to be delivered about science as a global enterprise, but Dr. Poskett has tortured it horribly into a caricature of what it should be, from the sounds of this interview.

Dr. Poskett, science is just science, it does not have a nationality or ethnicity. You cannot pull up it’s skirt to determine it’s sex or gender. There is nothing anti-modern about contextualizing the cutting edge science of its time as just that — of its time.

There was a pulse of technological innovation in Europe in the middle ages that is unprecedented in recorded history. Why did it happen? I don’t really know, most have heard the usual theories, Black Death recovery, Greek/Roman texts from Byzantium, Protestantism, who knows; I guess that’s something for the Dr. Poskett’s of the world to pontificate about. But to deny it does no service to anyone, just as it would do no service for me to go back 1000 years to 10th century Baghdad and try to convince the great Islamic scholars that the science of the pre-literate Vikings was on par with their own. That wouldn’t make me pro-Viking or anti-Islamic, it would just make me a fool, if we’re judging by scientific merits.

And if you had any doubts about where Dr. Poskett’s ideological motivations lie, just re-read the word salad that is his closing paragraph. Good grief. Not impressive for someone who places himself in the vaunted ‘White man who went to Cambridge’ class, and certainly not even worthy of a rebuttal here.

Thank you.

This seems like a pretty knee-jerk response to me. I don’t feel like anything he said was particularly charged ideologically. It seemed to be a fair and straightforward summary of some aspects of how the scientific enterprise functions cross culturally. His book looks like a good read to me, and his intentions seem well placed. Saying this as an American working scientist whose professional network consists primarily of foreigners (as is the case for most scientists these days).

As a fellow scientist, I would suggest that perhaps you have been marinating in a similar ideological brine for so long that what many readers find ideological, you barely notice.

“Science is science, it does not have a nationality or ethnicity.”

If only such a fact, and it is a fact, was used as a bulwark against the biases that creep up on psychologically overwhelmed humans as they navigate this increasingly complex journey we call life, things would be rosy. The reality however is a little less neat, humans lurch onto mental shortcuts and heuristics to abstract away the complexity of daily life, especially in commercial and professional settings where the stakes of bad decisions tend to be high. That is why you have “the country of origin effect” in the luxury goods sector where the geographical origin of products is used as a marker of quality (Italy and France benefit massively from this, that’s why the “made in France/Italy” is a marketing leitmotif for luxury brands from these countries). It is undeniable that the telling and retelling of scientific history in a way that shines the light of achievement on only one race can create its own “race of origin effect” in science, and has (at the most pernicious end of the interpretative spectrum, those who bask in the warm afterglow of the pulse of technological innovation emerging from white European males in the middle ages twist the historical narrative and seek to enshrine into received wisdom the notion that scientific excellence has a colour, and a gender, and that colour-gender pair is white and male).

These potentially pernicious heuristics don’t develop in a vacuum of course, and the telling of history is one powerful way in which they become culturally entrenched. It takes effort and a capacity for self-awareness for people in positions of leadership to guard against these heuristics bleeding into their decision making frameworks about things that have outsized impact on others (e.g. hiring). On a personal front, I’ve had people look at me askance on my travels because I’m a black African living in Africa, with a breadth of knowledge about the world, science, technology etc that was on par with or surpassed that of those I was interacting with (not hooting my own horn, just making a point that dovetails with the ones I made above re: unfounded assumptions about competence having a colour and a place of origin and how such socio-cultural myths develop and how a broader narrative around the history of science can mitigate against this).

If we start 5000 years ago and measure up until today, I would only make the case that the ‘white-male’ color-gender pair as you call it has been at the bleeding edge of science and technology for maybe 20% of that time (Greco-Roman era, Baroque period to present?).

But the fact that the most recent 8-10% of this time period has a certain origin and has had the most profound impact in terms of people’s everyday lives is inescapable. That’s bound to lead to some biases. We should guard against them as you say.

I think one problem (which the argument shares with a lot of people who “believe in” science nowadays) is that what exactly should be called “science” is not clear.

There were all sorts of wise and intelligent people who had certain, often insightful, ideas about how the universe worked, but how much of these is “science”? Did ancient Greek Democritus actually come up with anything like a real “atomic theory”? Of course not: modern science is a sociocultural phenomenon built on a lot more than a bunch of people with brilliant ideas (a notion that, unfortunately, the “great men theory of science” helped spread widely). This did not emerge anywhere outside the West and even there only recently–there is a good reason why some people call Newton the last alchemist rather than the first scientist. While I don’t dispute that there were plenty of brilliant alchemists everywhere, to call them “scientists” is misguided.

I only recently learned that the “Copernican” revolution had less to do with Copernicus than it had to do with Portuguese traders crossing the equator. Once the North Star disappeared, it was apparent to everybody except the Establishment that the Earth was not flat.

Around 250 BC, Eratosthenes demonstrated that the Earth is a kind of sphere. Also, many astronomers knew that the Earth was spherical from their study of eclipses. It was common knowledge that the Earth was a sphere since antiquity.

What Copernicus–and Galileo–showed was that the solar system is heliocentric. The planets and the sun do not orbit the Earth.

“By around 500 B.C., most ancient Greeks believed that Earth was round, not flat. But they had no idea how big the planet is until about 240 B.C., when Eratosthenes devised a clever method of estimating its circumference.”

https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200606/history.cfm#:~:text=Values%20between%20500%20and%20about,slightly%20less%20around%20the%20poles.

Copernicus himself was conservative. He switched the positions of the Earth and Sun but kept other features of the Ptolemaic system. What he didn’t realize (or maybe didn’t care) is that moving the Earth from the center of the universe blew the bottom out of Aristotelian physics. Copernicus’ successors like Kepler, Galileo, and Newton worked out the full implications of this.

If you have never had a chance to dip into Needham’s series of volumes on China, please do so. It is mind-blowing (or, better, perspective-disturbing).

Too much of the discussion of science in the Anglo-American world is the litany of Anglo-Americans, as the posting points out. Yet especially in mathematics and in “practical” sciences like metallurgy and agriculture, the scientific effort is worldwide, whether or not Anglo-American textbooks acknowledge it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science_and_Civilisation_in_China

Scientific thinking seems to be innate to our species and others as well— observation of material properties discerning cause and effect leading to novel understandings with predictive power and utilitarian applications. As to why some human groupings seem to have taken this process further than others, I think Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, does a convincing job of attributing these differences to opportunities and limitations determined by geography and environmental factors.

Today North American indigenous people are very cognizant of the problems surrounding the storage of spent fuel from nuclear power plants. They have developed basic protocols, primarily the idea that we should never think of abandoning it underground. They have scientific, cultural and moral backing for their point of view.

The Canadian Gordon Edwards has used their work to elaborate on how the U.S. and Canada can implement their views. The nuclear industry and the DOE are indigenous-washing by including the First Nations in “discussions” but ignoring their solution to this problem. “We” are intent on “getting rid of” the most dangerous material on earth that will last forever (in human terms) when it is obvious that this problem will never go away no matter how deep you bury it. We get rid of our plastic junk; then, lo and behold — it’s still here. We clean up chemical spills; then find that people are still getting illnesses because of polluted water, soil and air. PCBs have been banned, but they are still with us in the atmosphere, for many, many years.

Likewise, WE ARE NOT GOING TO BE ABLE TO RID OURSELVES OF THE WASTE FROM NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS. Native peoples are fully aware of this. ¿Why aren’t we paying attention?

because “science” also makes people “blind” to reality.

many a bright individual. see’s the “promise of some scientific fetish” as proof he/she/we; can break the laws of nature….and still expect impunity…….

How’s that for “un-scientific”

Necessary, so welcome but I have some questions about starting assumptions of the author. The little bit about Europeans discovering America and realizing that there are other people in the world is straight from the bad history we all get taught. Europeans knew there was a great big world full of people, though maybe not about the americas specifically. When the Portuguese started the age of exploratory imperialism they weren’t after spices and adventure. They were after gold, which they knew was in west Africa because it was recorded in the news from more advanced places like Egypt. But we’re really committed to the idea that we’ve always been more advanced than everyone else in order to justify our empires.

I wonder if the book deals with the socio-economic-political context of European science and its history effect on the history of science in a global context. If Darwin had not lived in the Dickensian nightmare of Victorian capitalism, would his theory have bent towards nature mirroring the ruthless competition of capitalism? Indeed, that’s not what he said exactly but his framing made it easy to draw those conclusions. And then most everything after that was built on those conclusions, even in evolution where the main argument has long been competition, right down to the “selfish gene”. Kropotkin’s theory of evolution as a cooperative process was clearly influenced by his anarchism. But it turns out he was more right than Darwin, at least so far as competition being rather friendly in evolution. How much scientific effort was wasted by westerners trying to prove that evolution resembled capitalism because we refused to listen to non-western scientific voices?

(I don’t think Darwin was wrong or bad. I think he was a product of his context like we all are, and if the book isn’t addressing science’s social context, can it reach the root of what the author is purporting to explore?)

Further to sfp, I just helped run a global conference (delayed from June 2020) of social scientists whose research focuses on the auto industry. Native English speakers were a minority, there are only 5-6 active members from the US. Intellectual activity is global, and within studies of the industry, one major research agenda [nod to Thomas Kuhn] grapples with versions of “lean” production/management, dating to 1960s methodologies developed at Toyota.

Separately, an example of global science in medicine is smallpox vaccination, which made its way from China to Europe, though using cowpox instead of human smallpox for vaccinations was Jenner. That however took 8 centuries. Historically there were a lot of independent discoveries, and another lesson from Needham is that things can be forgotten, “progress” is an Enlightenment concept, in China “science” as an endeavor ceased in the face of a changed political and related intellectual environment. As with smallpox, interactions might take centuries.

Of course there were embodied technologies, domesticated crops and animals diffused widely.

It sounds like an interesting read, I will be curious to see how Poskett defines “science” (as opposed to “knowledge”).

As a medical historian and lecturer of Medical History and Ethics, I am often deluged with either actual books or recommendations.

This one caught my eye a few weeks ago and was a fascinating read.

It brought up some very important points for our world today. It was Catherine the Great who among all the leaders of the world at the time, had the guts to take an inoculation and thus modeled behavior for her people and by extension the rest of the world.

Indeed, this is one of the most important events in all of vaccine history and it happened not in Europe or the US but in Russia, a fact that is widely ignored today.

This is also an account that I wish all of our leaders would read today. One of the fundamental jobs of leadership in a crisis is appropriate modeling behavior. How different things would be right now had that simple task been done by all of them early on. Keep cool. Don’t panic. Don’t politicize medicine or public health.

My impression is that people at the highest levels of authority seem, largely, to believe that’s what they did. If they regard their function as being social control, then you can make an argument that they’ve been fantastically successful.

Of course in this context “don’t politicize” means “don’t allow consensus that might lead to action”.

Fun note about Dimsdale from Good Reads:

Common sense and perceptivity, neither go out of style and both regain public awareness on occasion, too.

I took ‘physics for physics majors’ versions of the lower division physics sequence when I could get into them. I recollect the relationship between Nagaoka’s and Rutherford’s work being described in some detail, with full credit to Nagaoka. That textbook must have been written fifty years ago.

The teaching of university-level physics and math to students who won’t be specialising in those fields involves a lot of tactical dumbing-down. I think one inevitable consequence is that contributions like Nagaoka’s are unknown to people who have been given the impression they know a lot about physical science. In other words, we’re not merely chauvinistic, we’re fundamentally ignorant. And as the past two-and-a-half years have made all too clear, people who haved passed for ‘expert’ in the western world are all to often absolutely pig-ignorant about their own fields.

Science isn’t the only whitewashed subject in our understanding of ourselves and we got here. The philosophical foundations of the Ivory Tower on which scientific disciplines rest are assumed to be entirely of unaided Western doing:

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/11/opinion/if-philosophy-wont-diversify-lets-call-it-what-it-really-is.html

For example, if you want to learn about Chinese contributions to philosophy or science, we are told to go to the “Asian Studies” department. The implication being only white people know how to do “real” philosophy. Only such as Kant and Plato are “real” philosophers; we know so because we don’t have to go to the “European Studies” department to find classes about their works.

Spend some time steeping in Zhuangzi or Nagarjuna and ask yourself how anyone could call their writings “not-philosophy.” Read Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China and see how much scientific intelligence is “Eastern” once we let go of our indoctrinated ethnocentric view.

This isn’t realization isn’t “wokeism” but rather one of those great elephants in the room future generations will look back on and ask, how could they not see it?

I believe that too much of what has happened is blamed on bigotry. While much of the divisions in history, philosophy, and science have bigotry infused in them with John Dewey’s work an excellent example of the often conscious discrimination, if not outright denigration, of non-Western, non-White, and non-upper class work, much of it is still parochially based.

It think just as much of it comes from the isolation involved when those classifications and divisions were created. It was not like today where a letter, phone call, email, or text can easily be exchanged. It was more like weeks, months, even years, depending on when in history, to exchange messages. Then add the often haphazard, even chaotic, process of adding knowledge from outside European, American, or Western civilization.

Science, philosophy, education all are conservative with the focus especially in education of building on what already existed. Five hundred years ago, European or Western philosophy was just philosophy. Science, such as it was then, was just science. And both were heavily Greek and Roman focused. It is almost as if the whole process is on autopilot. It is doing things in certain ways because that is always how they were done albeit with the growing racism of the past four centuries increasingly enforcing some of the patterns.

It is also a human thing to put down others. It is not that hard to find some of the extremely arrogant comments of the Ottomans, Chinese, and Japanese in describing the Europeans. Granted the Europeans’ behavior was often barbaric and their arrogance no less, but still.

Re: “It completely skews the story if we have this exclusive focus on White European pioneers.” More wokeness in science and mathematics that should have ZERO wokeness. We all know that Europeans are WHITE but that has to be mentioned as Poskett spits out the word. Sort of like calling Africans “the BLACK Africans.” Perhaps some history book should call the Chinese explorers of the 14th century, “the LIGHT BROWN Asian explorers.

The Woke game is about division. It’s about elites playing the little people by having another subject for them to argue about so that class division (which is the real division in societies) will never be discussed.

There are a fair number of people who’ve lived quite a bit of time in Africa who aren’t “black”. In much the same way that there are a fair number of people living in North America who aren’t American, according to your definition. Just saying.

The hijacking and subsequent weaponization of the terms “inclusive” and “diversity” by the radical left to advance its own agenda has so tarnished those words that even when they’re invoked legitimately, as is the case here where the case is being made that the history of science needs to be told in a broader, more inclusive way, one can be sure that an accusation of using woke ideology to debase the conversation isn’t far behind. This reflexive dismissal of any attempt at recognizing that scientific endeavour, amongst other human endeavours, was, is and will always be global and that the historical account should, to the extent possible, reflect this, as wokeism, is just as problematic as the rabid radicals who trot out the need for inclusiveness as the tip of the spear to ram through sinister agendas.

This by the way is coming from someone who is anti-woke (and my past comments on NC bear this out) and has been fascinated with science since reading “The Einstein Decade 1905 – 1915”, “The Tao of Physics” and “The Dancing Wu li Masters” as a young boy. Recognizing the colossal achievements and contributions of men like Einstein, Schroedinger, Planck et al isn’t mutually exclusive with opening the debate on the need for a broader historical account of scientific development as a human endeavour.

My first job in “investment management” saw me witnessing discussions in a boardroom on the roof of a great building in Newlands Cape Town which would have been amusing if I hadn’t been so out of my depth. We junior people were assigned to sit on chairs around the walls of the room (intimidation?) while the meat of the discussion went down at the table. The person at the table … well I leave that to your imagination. This was after Mandela was released from jail.

Anyway, I got distracted. What I really meant to say was that in a smaller boardroom downstairs a black Zimbabwean person was hired (for some reason or other) and in the daily discussions he was almost universally ignored. Despite being the most sensible person around.

“And the narratives that scientists were taught and told themselves in the West was a narrative that was built for the Cold War.”

I find this statement very strange. First time that I’ve seen racism explained as an artefact of the Cold War!

When I did a physics major in the 1980s, the focus was on grasping the concepts and being able to manipulate the math with sufficient fluency. “Who discovered it” was generally considered beside the point. There was a history of science course for the humanities majors, but if a physics major took the course, it was considered a sign among us nerds that one lacked the seriousness required to do real physics.

Understanding that different universities may have had different approaches.

I don’t care what that German guy thought; I believe in Jewish physics.

As for the last five hundred years of science being largely European, blame it on the Mongols. Remember them, those folks with stirrups and compound bows who leveled most of the other Eurasian civilizations during the 12th and 13th Century?

Baghdad was turned into a small mountain of skulls, which pretty much finished off the local scientific community. China get the same treatment and evenually so did India. Slaves don’t have time for science and nomads don’t care.

Western Europe was saved by the woods. Even cavalrymen have to sleep occasionally and the enraged European peasantry coming out of the woods at night made the place uncomfortable enough that the Mongols eventually went after easier prey- the folks living on the plains. Hungary was unlucky; it was a flat grassland. The locals either got killed or ran, so we got this strange crowd speaking a central Asian language living between the Slavs and Germans. Kiev also got the kill-everyone treatment but Moscow was in the woods to the north so it survived.

Two centuries of Mongols cleared the way for the Europeans. The rest is scientific history. If you think the European imperialists were a unique form of genocidal maniac you haven’t read enough history. Compared to the Mongols, we were barely in the major league.

Science is neutral, but oligarchs aren’t. To establish trust in science we need far more than inclusive recognition of the world’s contributions – we need to stop being secretive, sloppy and pseudo. The prime example is American biolabs for military purposes. Let’s start there with detailed timely reports and not pretend that we can just open the tent up a tad and everyone will automatically trust science. We need very concrete action. We need trustworthy science.